Four years ago, the artist Hadi Fallahpisheh, newly graduated from the Bard MFA program, found himself with an expired visa, hiding out in a tiny upstate New York town on the eve of the American presidential election. In the large garage of the house he had rented, he set about making the artwork he has come to be known for — playful painterly photographs born of crude experiments with objects and light. As fall turned to winter, Donald Trump became the forty-fifth president of the United States, and Fallahpisheh faced the prospect of returning to his native Iran. Beside himself, he decided to mark that fraught moment with a performance of sorts — a plot to go out with a bang.

I never wanted to become an artist, honestly. It was my parents’ fault. My mother was a photographer, so I practically grew up in a darkroom, a mysterious place that stank of chemicals. When we misbehaved, she would lock my sister and me in there for hours at a time. It was a kind of jail. My father, a lawyer, was also a photographer. Rather than being sent to the front during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, he was given a camera and told to make propaganda for the war effort. I said, If this is art I don’t want to be an artist! So I rebelled against my bohemian family by entering an electronic-engineering program.

I failed all my engineering classes. But before getting kicked out, I did take a filmmaking workshop and became interested in film. This was around 2010. I started recording things around me with a digital camera. I also started taking photos because, I guess, I couldn’t get away from my family of photographers even if I really wanted to.

My first major project involved photos of stray dogs at nighttime. I thought they were very artistic! [Laughs] I tried to shop them around. I must have been twenty-one or so. There was one gallery in Tehran that specialized in photography called Silk Road, and I would go to all of its openings to drop off my latest photos and CV. That kind of thing. I was also using Facebook a lot at the time. I would write to people out of the blue and say, “Hello, I’m an Iranian photographer. These are my photographs. Can you advise me?” You know what? People actually responded! Suddenly, I was Facebook friends with people in New York and Los Angeles — all over the US, actually. No one had really responded to my work in Iran, but then these random Americans were writing to me. Some of them introduced me to Gregory Crewdson’s work — I guess he was hot at the time — so I got interested in staged photography.

But not the sort of staged photography you might expect. I would shoot still lives of animals, fruit — stuff like that. Maybe it was childish? It probably was. There was pressure to make art that had weight, that was “worthy” and profound, especially in the Islamic Republic, and I was somehow running in the opposite direction. I suppose I was more interested in pulp and popular culture. A friend of mine worked for an internet-service provider, and he would give me free high-speed downloads. The internet was so slow in Tehran at the time, so this was a big deal for me. I remember downloading fifty movies that had just one star on IMDB. Which is to say, fifty of the worst movies ever: kung fu movies, Spaghetti Westerns, low-budget horror films. The anti-Kiarostami. I really wasn’t interested in highbrow.

Eventually, I did a photography project set in my grandfather’s garden, which was outside of Tehran in a village called Kordan. It was tended to by undocumented Afghan immigrant farmers. I brought out some lights and began shooting the garden at night. Imagine brightly lit images of cucumbers and watermelons. I hung cherries from a tree. They almost looked like crime scenes. When I got an offer for an exhibition, I was very happy. This was back during Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency, which, as you know, was very conservative, so we had to submit all work to the censors at the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance beforehand to get permission.

Only five days before the show was set to open, I was told the ministry had rejected it. I really had no idea why. Well, my uncle had some government connections, and I asked him if he could look into my case. It turned out that the person who reviewed the work found it too sexual! Apparently, he thought the watermelon was more than just a watermelon — that my work was made up of secret sexual symbols. Someone has to be extremely oppressed in the head to think these things, no?

I thought, Okay, this is the end of my life. My exhibition wasn’t happening. Ahmadinejad was president. A friend had just been arrested; another friend had been killed during the uprisings of 2009. I had been arrested then too. Everything was going wrong. I told my parents I had to leave Iran. I told myself I had to go somewhere where they might appreciate what I was doing.

At the time, I happened to have a digital copy of the book Analogue, by Zoe Leonard. Someone, probably one of those Facebook friends, had sent it to me. Access to books about art — to international books in general — was so limited in Iran at the time because of sanctions and internet censorship and the shitty mail situation in general. At best, you might be able to read the first paragraph of an article in Artforum, but that’s at best. A little Bidoun here and there, back issues. I was hungry for art from the rest of the world, and became obsessed with whatever book I happened to have access to.

In so many ways, that Zoe Leonard PDF changed my life. Her book, and Google, led me to the Bard MFA program, where she was teaching a tthe time. I applied and got in. I felt very lucky. But I made two very big and important mistakes. First, I didn’t know that Bard was upstate — I mean, I didn’t even know what “upstate” was. I just imagined “New York” meant New York City. Second, I didn’t realize that my two-year program only met during the summers.

So it turned out that I was escaping one kind of isolation for another. Bard was like my grandparents’ tiny village, where I had been spending most of my time up until I left Iran. And the fact that I was enrolled in a summer program meant I wouldn’t be eligible for the standard one-year OPT visa given to international students as they graduate. When, after two happy years in America, I finished school, I was told I had one month to leave the country.

I panicked. I wasn’t mentally prepared to go back to Iran. I also wasn’t thinking clearly. I thought I might manage to get an artist visa — but in any case, I was going to stay. I couldn’t afford to move to New York City, so instead I moved about thirty-five minutes north of Bard to a tiny rural town further upstate. This was September 2016. I managed to find a cheap place with a huge garage I could use as a darkroom. I didn’t have any equipment. I’d brought some of my mother’s equipment to America but had sold it after the first year because I needed the money. So I asked myself, What would happen if you tried to make photographs without a camera? That’s the story behind much of my work you see today: experiments with objects, photo paper, light, and darkness.

Courtesy the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York

There was absolutely nothing around. The closest grocery store was more than twenty minutes away. I basically had five neighbors, all of them racist. I didn’t realize they were racist until I did what any decent Iranian would do, which is take them a gift a short while after I moved in. I came bearing four different types of cookies and said, “Hi, my name is Hadi. I’m an emerging Iranian artist.” I knew something was wrong when they didn’t give me anything back. I mean, that would have been the polite thing to do.

A couple of months later, the neighbors planted Trump flags in their front yards and attached Trump flags on their cars. That’s when the harassment started. Whenever I bumped into one neighbor, in particular, at the grocery store, he would loudly announce, “The Iranian is here!” and ask how I felt about the new president. I would avoid the store whenever I saw his car out front or drive around the block for five or ten minutes until he left.

Then came the ICE raids. I got very lucky. A man who would occasionally bring me firewood called me one day out of the blue. “Hey friend,” he said, “ICE is in the area looking for illegals.” He was from Mexico and knew I was undocumented too. I hid in my garage for five days with all the lights off. I’m so grateful to him.

By that time, I was sure I had no chance of getting a visa — the Trump administration had stopped processing Iranian visas altogether. I was running out of money. I remember I managed to find a cheap plane ticket back to Iran. But before I left, I wanted to do something special.

That’s when I came up with the idea of the Molotovs.

Do you know about Trump wine? I didn’t… but then I did. I can’t really tell you how good or bad it is, as far as wine goes, because I grew up drinking shitty wine in Iran and it all tastes the same to me — fine! But anyway, discovering Trump wine gave me an idea. I used the last bits of my savings to buy as many bottles of it as I could. I drank it all. Then I filled the empty bottles with gasoline to make Molotov cocktails. Trump cocktails. I imagined taking them to Trump Tower and throwing them at the building surface. Of course, I wanted to be sure not to hurt anyone. I also wrote a song that I would perform at the site. It’s called “Ne Me Quitte Pas.”

The plan was to get deported. I even wrote to Tony Shafrazi — I was thinking of his infamous spray painting of Guernica in 1974, how he had entered history by defacing the most important antiwar painting in the world. Of course, he never wrote back. I wrote to other people I knew (and some I didn’t), artists and writers, hoping I might present my idea, and that they would write about it if I ended up getting arrested. I met with some of them. Can you imagine? You’re sitting at a café, and I bring out a Molotov cocktail and put it on the table. “Hello, I am Hadi and this is my art.” Many of them went quiet. One offered to pay for therapy.

Courtesy the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York

Obviously, I was going a little crazy. But I did believe in the value of this experiment as an artwork, as a performance. I was going through pain, and I wanted to transfer that pain to an object. Someone said to me, “Hadi, you won’t be deported, but you might be killed or arrested or sent to Guantanamo.” That was helpful information. I adjusted my plan. I thought, Maybe I could light the Molotovs and throw them in the Hudson River? Then a new idea: How about if I bury each one with a letter? A little like a time capsule.

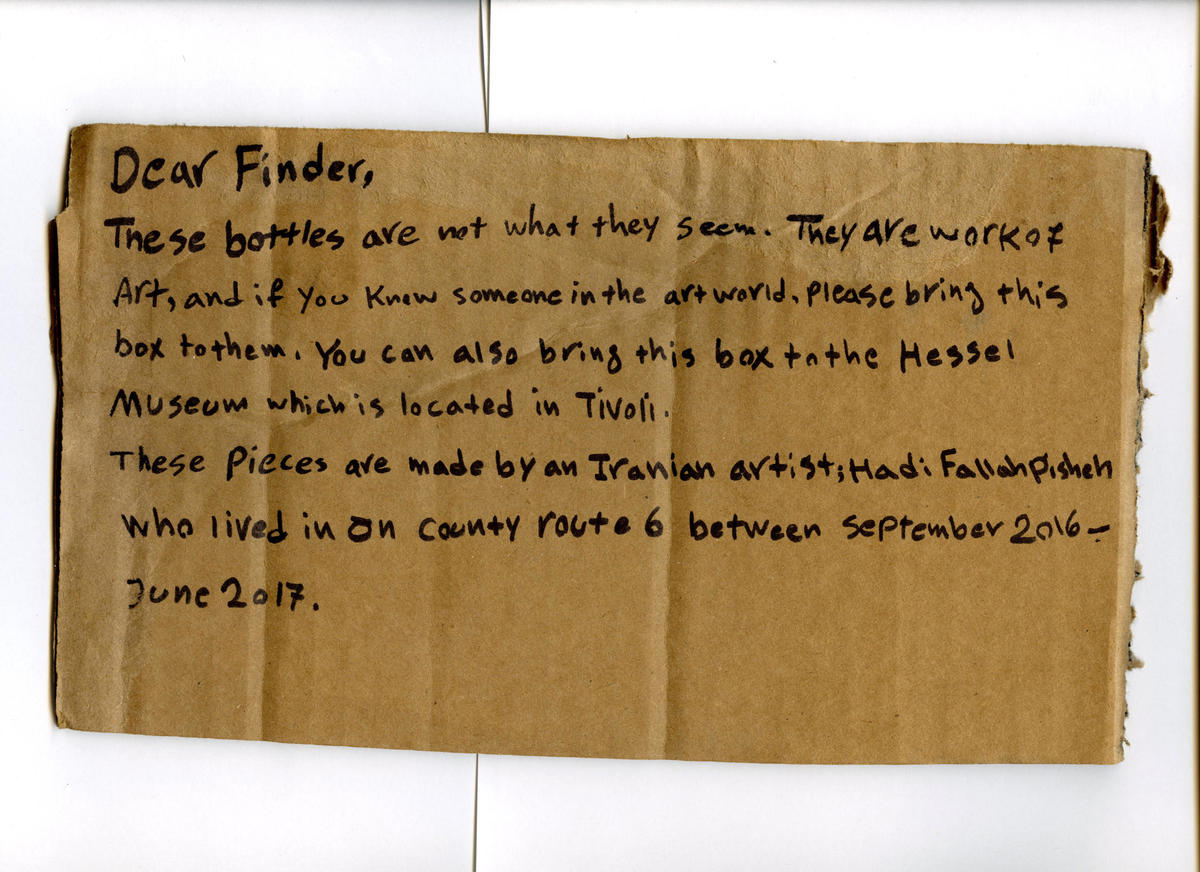

I made four boxes and wrote a letter for each, introducing myself, my situation, and this sculpture as my work of art. I buried the boxes in open fields off of Route 6 upstate. In each letter, I asked anyone who found the object to take it to someone who might appreciate it. Twenty years from now, two hundred years from now, whatever, someone might dig it up and say, “What the fuck is this?” Then they will read my letter.

Life went on. I ended up getting a visa and some shows, and everything worked out after all. I forgot about the buried Molotovs.

During the pandemic, my girlfriend, Phoebe, and I, like everyone else, were drinking more wine than usual. One day, we were sitting around, and I made a joke about how strange it was that liquor shops were considered “essential businesses.” Then I remembered the Molotovs. Phoebe said I had to find them. She insisted. It would be an adventure.

We went to Home Depot to buy shovels and drove upstate that weekend. Miraculously, we managed to dig them up. All four. It was a little like digging up a trauma or a person from the past, a dead body. Of course, all the gas had evaporated. But there were the Trump wine bottles, like carcasses, the letters intact.