In the marketplace of ideas, there are no figures so sad, yet so hopeful, as mid-list authors pushing not-so-recently published books. Whether hawking their conceptual wares as talking heads on cable television, or spilling intellectual lifeblood on the sands of social media, or selling themselves on ill-conceived and ill-attended panels, our nonfiction writers, ex-generals, early childhood learning specialists, longevity gurus, associate professors, and novelists are a faltering regiment caught in a pincer between the flinty remnants of corporate media and the zombie-like audiences eager to feast on their brains.

There is a misperception that this creature is a new arrival to our cultural scene, but the anxious adjuncts of middlebrow American aspiration have been around for at least a century and a half. Consider the Chautauqua Institution. Founded in 1874 as a bucolic training ground for Sunday school teachers, the institution became the first American correspondence school, offering lessons on a vast range of topics and conferring degrees by mail. Families and religious groups made the trek to Chautauqua, way upstate in the Finger Lakes region of New York, overwhelming the institution’s limited lodgings for weekend seminars and workshops. Unaffiliated “Chautauquas” started popping up across the United States, and with them grew an informal circuit of poets, essayists, explorers, magicians, and gurus, as well as reams of flyers, posters, and pamphlets produced to promote them. The University of Iowa maintains a library of these advertisements, and, in addition to being an old-school look at the art of infotainment, they also serve as an index of stratagems for selling the self.

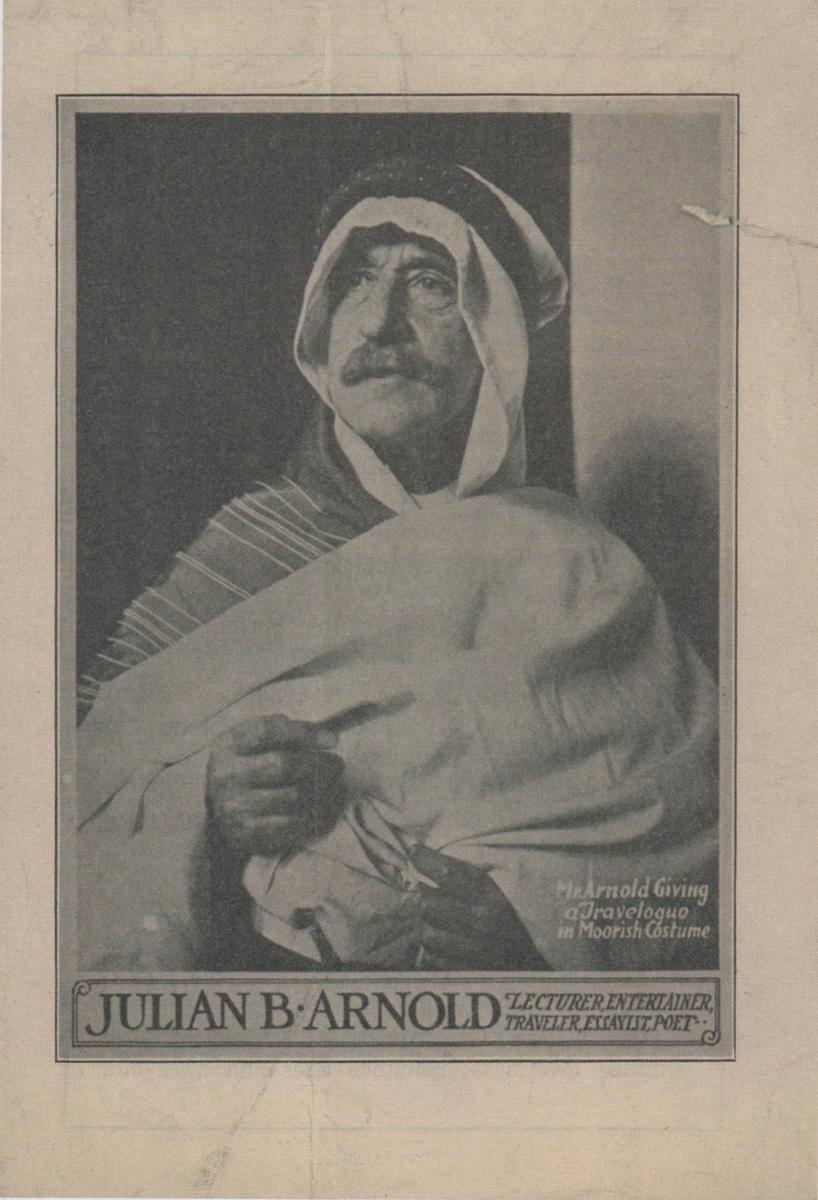

Julian B. Arnold

Who wouldn’t want to spend an edifying summer evening with Julian B. Arnold? Although Mr. Arnold’s visage suggests a man whose days of adventure are squarely behind him — his is not a young face — the look in his eyes tells us it is not necessary to view this as a diminishment or reduction. He seems the kind of wise gentleman who has not only made peace with his encroaching dotage, but found a modest profit in it. A well-traveled man with a multifaceted portfolio like Mr. Arnold’s would not be unfamiliar with the tall, the colorful, or the exaggerated, but such fripperies are not for him; where others endeavor to hold the void back with boasts and shouts, Mr. Arnold seems to wish to invite it over for tea. His garb — Moorish costume, according to the caption — indicates Mr. Arnold’s taste for comfort. No wonder, then, that the listings of antique booksellers reveal that Mr. Arnold authored a book called Giants in Dressing Gowns, described as an intimate and private report of the great men and women Arnold had occasion, over the long years of his life, to know: Grover Cleveland, Robert Browning, Conan Doyle, Andrew Carnegie, Queen Victoria. A life of sideways encounters with such luminaries might leave some men perturbed or resentful, but Julian B. Arnold prefers to recollect these near misses as proofs of the world’s order and goodness, carefully recorded in the warm light of the parlor fire. Perhaps precisely because he has seen the harsher parts of the world, Mr. Arnold enjoys returning home to the enveloping and the silken. The sheet-like expanse of white around his chest seems to have been freshly laundered; the shiny fabric at his shoulder suggests a soft, oceanic blue interwoven with the finest white threads. One imagines that every time Mr. Arnold inhaled at the lectern, his nostrils filled with a pleasant, clean scent, a whiff of newness and renewal. The only sign that all has not been right in the world are his hands. They seem at once roughed and swollen, either from overuse or from that arthritic retention of fluid that sometimes afflicts those of advanced age. One worries that these hands are a source of pain to him; but no one would mistake Mr. Arnold for a softy.

V. E. I. M. Ilahi-Baksh

The cautionary lesson of V. E. I. M. Ilahi-Baksh’s pamphlet is that the lot of the exotic man of learning in the Americas may be marked by sudden reversals and betrayals. This is announced immediately on the cover page of Mr. Ilahi-Baksh’s pamphlet. The name of his manager, one J. H. Roshindi of Bloomington, Illinois, has been crossed out, replaced by what appears to Ilahi-Baksh’s own name, or that of someone bound to the lecturer by blood. Mr. Ilahi-Baksh has apparently ventured out on his own, but why? If there has been an offense, it is lost to history. Exigencies of cost or time have prevented the printing of new materials, and this particular specimen seems to have done double duty as a solicitation for work and an audience-facing advertisement for lectures. The recommendations of Chautauqua functionaries testifying to the quality of the lecturer’s services are marked in pen, and one imagines Mr. Ilahi-Baksh highlighting their praise just before pressing these pages into the hands of a booking agent or circuit manager. The pamphlet makes ample and regular mention of the speaker’s mastery of the English language, but one cannot help worrying about his prospects. If only a fool hires himself as a lawyer in a court of law, the performer who becomes his own manager is often on the express train to Palookaville. Producing and performing call for distinct skills and outlooks, and the exhausted, inward cast of IlahiBaksh’s eyes, the set of his mouth, suggest a man who will have a hard time keeping his professional personae and their associated demands distinct. This photo was clearly taken back before the manager’s erasure, and for all we know poor J. H. Roshindi simply fell to a Bloomington sidewalk one day, struck down by stroke. All the same, one imagines that even during the sitting, Ilahi-Baksh was nursing a bad feeling about his manager, an intuition that things would soon go awry.

Mbonu Ojike

There is something understandable and familiar, but nonetheless unlikable, about the loving esteem with which this African Horatio Alger, Mbonu Ojike of Nigeria, holds his microphone. He regards the instrument of his upward mobility in America the way one might regard a wife, a child, or a meal. The scene the shutter has captured with Ojike’s eyes frozen midway through an appraising sweep of the mic, can only conclude with a deep sigh of appreciation.

Mr. Ojike’s biography reveals a formidable single-mindedness, a trait that has clearly brought him a great deal of success — a fine suit, a gold watch, a sizeable pinkie ring, an article in Harper’s, representation, a book deal, an opportunity to share his thoughts about Africa from the soundstage of Chicago’s WBBM, the waggish luxury of a stylish high-part shaved into his closely cropped hair. Time and successive cycles of scanning have reduced the paper Ojike holds to a blank sheet of white, but to imagine this man tied to notes and talking points is to misunderstand the specific trajectory that has brought him to Chicago. Who better to extemporize at length, and on a moment’s notice, on the topic of the new African than the genuine article himself?

That such a figure should have been so feted at the epicenter of the Great Migration from South to North is not unexpected, although one has reason to wonder where Ojike stood on the great issues of the racial day. The only date cited on the pamphlet refers to his 1945 Harper’s article, this on “Modern Africa,” and his then-forthcoming book seems concerned mostly with the question of Caucasian–African amity. Then there is the hazy white woman over his shoulder, hovering behind the booth’s glass. There is a terrible, awful slur about some mobility-minded men of color (often circulated by other men and women of color) that the craven will gladly turn their noses up at the oiled princess of their own lands while looking with favor on any Euro-American woman without regard to beauty, station, or skill, on the basis of her aspects as forbidden or proscribed. There is no futuristic treatment of sharpening or enlargement that could reorder the pixels of this ghostly apparition in a configuration that might strike our eyes as alluring or attractive, but who can say how she might have struck Mr. Ojike in the late ’40s, whenever he chanced to look away from the microphone, over his shoulder, and through the glass.

Thaviu and his Oriental Band

The mysteries of the Orient being mysteries, they only reveal themselves after careful study. Along with their baroque costumes and puffy hats, the chief appeal of the Oriental Band seems to be the scholarly cast of their cornetist and bandleader, the man they call Thaviu. We are told that Thaviu has studied the art of proper breathing, that he has enjoyed the unusual advantages of musical study under the best masters in Paris, and one imagines that his solos in the Oriental Fantasie, his take on the work of Liszt, were at least highly competent. In 1922, though, the year this pamphlet was published, Louis Armstrong traveled from New Orleans to Chicago to play with Joe “King” Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, Fats Waller churned out close to two hundred piano rolls, and Duke Ellington made his way up the American East Coast on his way to an epochal encounter with New York City. One wants to offer Thaviu and his Oriental Band sympathies for clearly having bet upon the wrong pop-cultural horse, but it is difficult not to see their posture as a response to the incipient, soon-to-come swellings of the Jazz Age. They were not Negroes, the pamphlet assures us; they have done their homework.

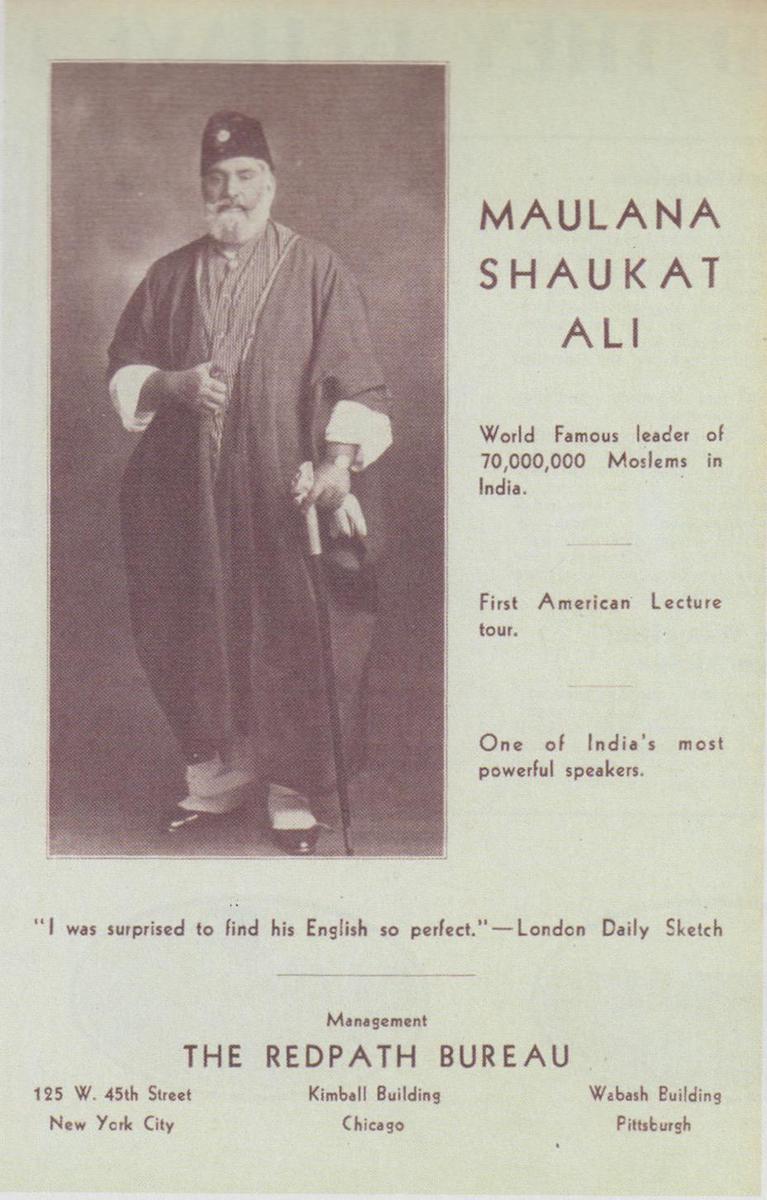

Maulana Shaukat Ali

With this pamphlet, we come across something that might be a bona fide historical document. It is pointless to quibble that Maulana Shaukat Ali was not technically the head of seventy million Muslims at the time of his American tour, but even though he would die almost ten years before independence and partition, he was still a key player in his region’s politics and a close political ally of Muhammad Ali Jinnah. His tour reveals Chautauqua as a kind of prototype of a Sunday morning public affairs program, an ancestor of today’s protean news-entertainment complex.

As much as Maulana Shaukat Ali’s tour seems a noteworthy and bygone event — who goes on such tours today, save popes, Obamas, and Dalai Lamas? — his managers nonetheless have their eyes on familiar prizes, alerting the potential attendee up front that one British listener was surprised to find Ali’s English “so perfect.” (What sting such an assessment might have held for Maulana Shaukat Ali, a well-educated newspaper publisher, is not recorded in the pamphlet.) In addition to intelligible phrasing, he also promises to be an interested visitor to America, full of “original comments about the American men and women” that will be “rather interesting and novel to the people of that continent.” This last is decisive: even in 1928, what American audiences wanted to hear about most was themselves.

Nirmal Ananda Das

It turns out that the Chautauqua Institution still exists. In addition to what seems to be a series of well-regarded festivals and workshop programs in dance, fine art, classical music, and theater, there are still lyceum sessions on the New York coast of Lake Erie, on such topics as “Sport in America,” “Restoring Legitimacy to our Election System,” and “The Ethical Frontiers of Science.” The classes are affordably priced ($116 for a weekend pass) and, judging by the organization’s website, their ideal attendee seems to be the type of progressive, middle-aged Crocs-and-star-of-India-skirt-wearing woman who listens to public radio. This demographic is to be much admired, but among its key weaknesses is a soft spot for a certain strain of multi-spectrum New Age mumbo jumbo best exemplified today by Deepak Chopra, king of the soft-focus shills of self-realization. One would say that from Nirmal Ananda Das to Chopra extends an unbroken lineage, except that among their chief propositions is that there is no such thing as time. Sinclair Lewis once derided Chautauqua as “nothing but wind and chaff and… the laughter of yokels,” but perhaps he couldn’t hear its fourth signature sound: the murmur of Om, the mystical syllable.

Jim Wilson

It’s easy for the contemporary observer to be put off by Mr. Jim Wilson’s lecture on the basis of its blaring headline. YES! AFRICANS ARE PEOPLE! But if we suspend judgment for a moment on the limits of 1930s racial progressivism, we find ourselves confronted with a truly classic American type: the dirty, backpacking hippie. From beginning to end, this pamphlet seems aimed like a laser-guided temporal missile at the bleeding hearts of the as-yet-unborn legions of young Americans who would begin setting out some twenty years later for every corner of the globe. Like Mr. Wilson, this later generation would make their own 4,500-mile journeys across various dark continents, scrounging around, sampling the local delicacies, and coming to the part-banal, part-transformative conclusion that pretty much everywhere you go, human beings are basically the same.

The other thing that becomes immediately apparent from perusing this pamphlet is that your elderly, distrustful grandparents were correct. Hippies are, in fact, total commies. Wilson’s claim that “he is telling you about yourself, and your children and your friends, struggling along in jungle and desert” is clearly communist propaganda. When he says he is “painting for you the valiant epic” of what it is to be born of “suffering women” and “work a little, play a little, laugh a little, cry a little, forge ahead a little, and die,” he conjures Che Guevera, Wilson’s journey a kind of Motorcycle Diaries avant la lettre. At the same time, the images of bared native breasts ensure a steady stream of pent-up attendees ripe for indoctrination. There are horny boys and nascent fifth columnists in every small town, and Mr. Wilson understands they are often one and the same person. His problem is the one that faces every itinerant recruiter, whether working for the commies or the Krishnas — how to best convert one into the other.

LoBagola

Within moments of laying eyes on the pamphlet for Bata Kindai Amgoza Ibn LoBagola, you know with an abrupt, instant certainty that you very much wish you could have attended one of his talks. No, scratch that: this is a man for whom you very much wish you could have bought a drink. Whatever chasm of race, generation, religion, or era might have loomed between you and this 1920s literary sensation instantly collapses. Why? Because Mr. LoBagola wears no shirt. Or more precisely, you feel this way because of the confident, muscular self-assurance and insouciance with which Mr. LoBagola wears no shirt. For all you know, he sits on the other side of the frame without a stitch of clothing beyond a prop loincloth and finely crafted pocket watch. On him this combination is neither contradiction nor the stuff of cheap irony, it is the essence of transcendent style. His portrait is timeless; Annie Leibovitz could have taken it yesterday. You want to have a drink with Mr. LoBagola (and you will want pay for the round, too) because you worry that otherwise he might look into your soul, find you wanting, and proceed to kick your ass. It would certainly be within his power to do so. That picture is nigh on eighty years old, and he knew even then exactly what you would be thinking the second you saw it. Better than anticipating your reaction, he meets you a good deal more than halfway in order to bowl you over, push you to the ground. “I am LoBagola,” he says, while looming over you, blocking out the sun. “Oxford lecturer, bushman, acclaimed author, husband of six, father to nations, and Jew. You want to make something of it?”

Mr. LoBagola’s managers at the Pond Bureau lack half the relaxed brio of their client. The pamphlet they have crafted is a weakling’s solicitation composed in the form of a neurotic’s lament, Mr. LoBagola imagined for the reader as a classic victim of doubled consciousness — “too refined for the primitive crudities of his tribe and too wild for sophisticated society.” This clearly bears no relation to the facts of Mr. LoBagola’s life. The scene his pamphlet sets of a young Mr. LoBagola being “on the look-out for apes and hook-lizards” misrepresents what was actually a Bunyanesque wrestling match. Mr. LoBagola did not find himself running naked through the streets of Edinburgh at the age of seven through a strange freak of circumstances; he took Edinburgh by storm, and the city has yet to recover. Even the description of his marrying his allotment of six wives in a single night at the age of eleven does him short-shrift, neglecting as it does to account for the dozens of half-Scottish/half-Bushman children LoBagola fathered in Northern climes between the ages of seven and ten. Of his “Judaist” religion the pamphlet is also of little value, but the lack is less a reflection on his publicists than on LoBagola being quite literally ahead of his time. The 1948 partition of Palestine had yet to occur. LoBagola’s Judiasm is not the backward-looking, archeological aside of long-lost black Jews the pamphlet would have you believe it to be. It is rather something forward-looking and unmade. LoBagola is the first Israeli. If he had been at Entebbe in 1976, during the storming of the hijacked airliner, he would have been both Idi Amin and Commander Netanyahu.

Of the so-called fact that he was born Joseph Lee Howard in Baltimore, Maryland, and died a pauper in Attica Prison, the less said, the better. What kind of fool looks away from that face to contemplate the dead ink on a birth certificate?

Alonzo Moore

The esteem with which the so-called Moors are held by the African in America has been well documented, though, as is the way of such things, it has waxed and waned over the years. As Brother R. Jones-Bey, current Grand Sheik and Moderator of the Moorish Science Temple of America, explains, these shifts in affection are not a matter of changing times or fashions, but of the lost finding themselves — and managing somehow to lose themselves again. As Jones-Bey explains the catechism, “You are not a Negro, you are not Black, you are not Colored. Nor are you Ethiopian. These names were given to slaves by slaveholders in 1779 and lasted until 1865. Here in America you are recognized for having a nationality. We are descendants of Moroccans, born in America. We are of Moorish descent.”

Like a dove flying in and out of a hat, the lost-found nation of North American Moors has appeared and disappeared many times from the national stage. During the period when Alonzo Moore, Prince of Oriental Magic, was working, this metaphorical cycle was often literal for the doves involved. The hat trick that has become a staple of almost every child’s fantasy was performed by magicians who often relied on spring-loaded hats and tables that not-so-magically disappeared the animals by crushing them in constricting steel compartments — the bunny or bird that “reappeared” on stage a temporarily lucky cagemate. Mr. Moore’s pamphlet indicates that he worked with animals, using them in routines perfected after long years of study in Morocco, “land of his ancestors.” Reference is made to such feats as “Birds of Paradise,” “The Goose that Laid the Golden Egg,” “Goose and Gander,” and (most ominously) “Bunny’s Misadventure.” We cannot know whether his particular versions of these tricks were fatal for their co-stars. In any case, Mr. Moore seems like a man of gentle and good humor; in three of five portraits, he resembles nothing so much as a genial page. As a black professional working America’s racially segregated small towns in the 1910s and ’20s, he likely had a more-than-passing familiarity with the awful, random processes whereby the doomed are separated out from the temporarily spared for the purposes of mere entertainment. In the 1920s, the decade the pamphlet was printed, hundreds of black men were lynched in America, and the same archives that saved Mr. Moore’s advertisement for posterity often contained the postcards and snapshots made to commemorate what were festive and carnivalesque occasions for every attendee — except, of course, the central attractions.