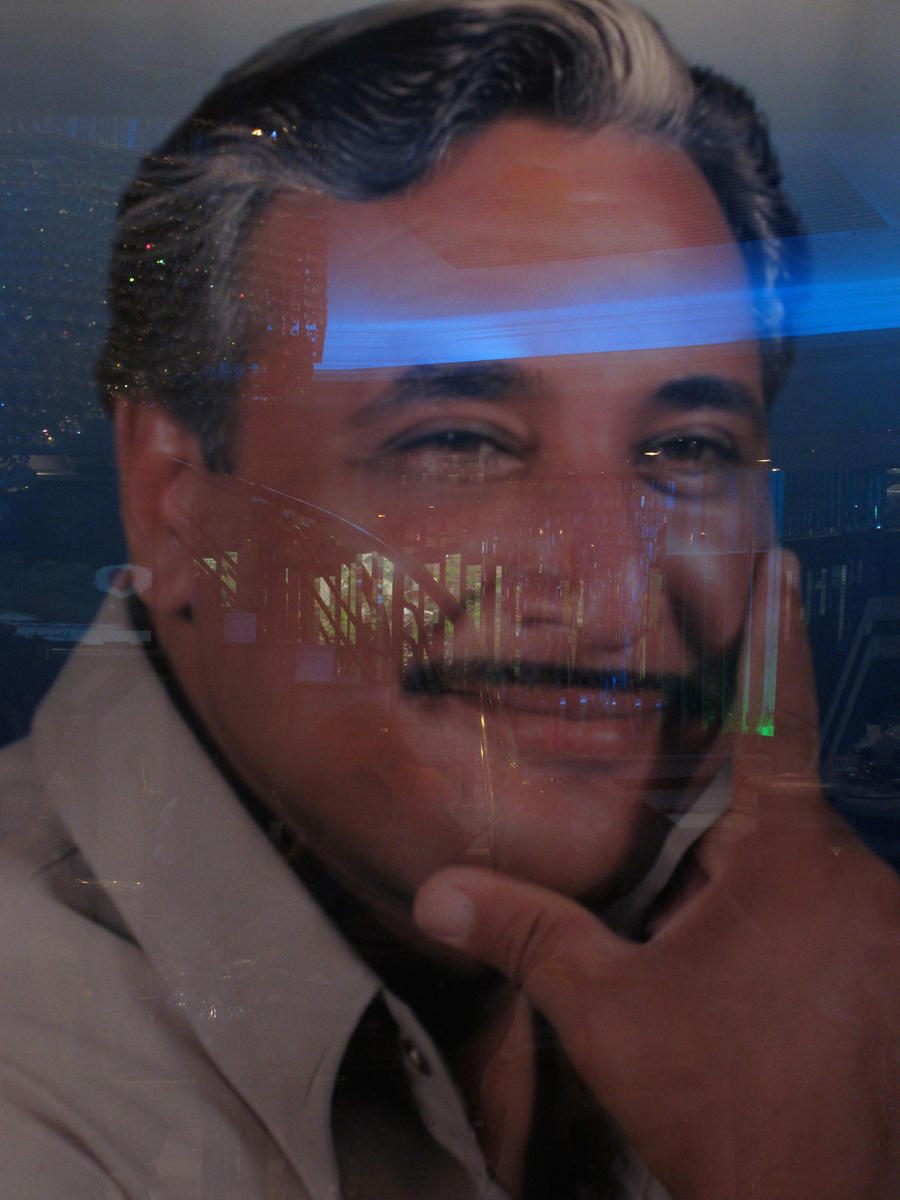

Abou Tarek Koshary is located on the corner of Maarouf and Champollion streets in the heart of downtown Cairo’s hectic car mechanics district. At night, the multistory building, fashioned mostly from concrete, is lit up with hundreds, if not thousands, of neon-colored lights. Making my way through the crowd of truck drivers, car mechanics, vegetable sellers, and loitering teenagers at the entrance, I find one of Abou Tarek’s youngest sons manning the cash register, surrounded by images of his father. He directs me up the stairs. On the second floor, I’m confronted with an older son, similarly surrounded by pictures of his famous father in all manner of crystalline and gilded frames. This son directs me farther, up to the third floor, where the father himself, Youssef Zaki — otherwise known as Abou Tarek, a man of considerable girth — sits at the cash desk amid portraits of himself, along with various framed articles that have been written about him and his business over the years. Indeed, there is little doubt that this purveyor of koshary — a traditional Egyptian dish of rice, pasta, lentils, onions, and spicy tomato sauce — is one of the most iconic figures in Egyptian food life.

Those who don’t have a past get lost. When I was thirteen, my father died. I had to leave school to support my mother and the rest of the family. Back then, most young people dreamed of leaving for the Gulf to make their fortunes, but for me, leaving wasn’t an option. That’s when I started selling koshary in a little cart. And that’s when my life really began.

I would stand with my cart on this very corner, where the restaurant is today. I didn’t have a proper permit to run a business, at first, so I used to hide my cart from the police. It was harassment from the police that pushed me to start looking for a shop. There was an old man from Upper Egypt who had a small coffee shop here. There wasn’t much to distinguish it from any of the other cafes on Champollion Street, and by 1989 he started to think of retiring and returning home. Besides, the coffee shop was not doing so well. One day he started letting people know that he was thinking of selling his space. Of course, I didn’t have the money to buy the shop, but I knew that this was an opportunity that I couldn’t pass up. I went to him one day and suggested giving him a small down payment and then paying off my debt through monthly installments. Surprisingly, he agreed, and suddenly I found myself inside rather than on the street. It took me about three years to pay off the debt, but even then business was good and all my customers knew me. Having a space also meant I could serve koshary for most of the day, not only at lunchtime. Once I owned the place, I started to think about expanding. It was more of a dream than anything — but as you can see, a dream that came true. And I’ve been in the koshary business for over fifty years now. How’s business today? Well, because the price of meat and chicken has gone up so high in Egypt, most people can’t afford them, and that’s meant that koshary has become more of a staple than ever before. Koshary is vegetarian, delicious, and cheap. You can see why it’s the best option in times like these. We don’t just offer koshary — we provide what I like to think of as five-star surroundings. We’re like the Four Seasons of restaurants! We’re a mall of koshary, where people come for the food as well as for the atmosphere. Imagine — foreigners pay up to fifty Egyptian pounds for a plate of koshary in one of the big hotels, and yet they get better treatment and food for a fraction of that here. Our facilities are clean, and we don’t allow smoking because there are many families coming and going. We offer koshary from three pounds a meal to ten pounds a meal, catering to everyone’s budget. That includes the mechanics and street vendors as well as the people who live beside us in this neighborhood.

People from all areas of the city come to eat here, including the upmarket areas of Zamalek and Mohandisseen. Local Egyptian companies also order lunch for their staff in the morning and send people to collect it throughout the day. In the summer, many families come downtown to walk around — especially at night — and again, we are especially busy then. Tourists are finding their way here, too. We have tour buses coming every day, bringing mostly Japanese and Emiratis. Even the ambassador to Germany comes to us and brings his wife and his friends. Some Egyptian actors, the late director Youssef Chahine, and the ministers of health and the environment are others who have come here. But everybody gets the same treatment at my place.

Abou Tarek is “Malek El Koshary,” or the King of Koshary. Journalists from a French newspaper gave me this name. They once wrote an article about me, and the title of that article was “The King of Koshary.” From then on, everyone started to call me by that name. It stuck. I have a sign outside that says, “We have no other branches,” because in the past others have tried to use my name. I want people to be sure that they are eating at the one and only Abou Tarek. We’re growing, too. We just added a fourth floor that will be ready after Ramadan, and then I will start construction on a fifth floor in the new year.

What I have accomplished is God’s blessing. And there are those who prayed for me over the years, especially my mother. But one of the most important reasons for my success is the help and support I have had from my neighbors here on Maarouf Street. Abou Tarek Koshary is not just a place where one man makes koshary and sells it. There are over twenty women from the neighborhood who work together making the food — everything from the macaroni to the secret sauce. Some of them were forced from their homes and sent out to the outskirts of the city to live in cheap government homes, yet they still come in every day to work with us. We’re like a big happy family here.