My uncle built this store in 1939. Back then, one side was a beauty shop and the other was a fish market. He lived in the back. When the Second World War started in 1942, all Japanese-Americans in the three Western states — California, Oregon, and Washington — had to leave. If you happened to be single, you could just pick up your suitcase, catch a Greyhound bus, and go. Still, where would you go? And if you had a family or a house or a business, it was even harder. What would you do in Idaho or Iowa? So the majority of Japanese-Americans stuck it out. And that turned out to be a terrible mistake. By March 1942 President Roosevelt signed an executive order incarcerating all Japanese from the Western states. They were put into “relocation camps.”

I was three years old then. First we were sent to the Santa Anita racetrack, because they hadn’t finished building the camps yet. From Santa Anita, we went to rural Arkansas; there were at least two camps in Arkansas. I’m sure if I looked into the history, I’d find out that the senator from Arkansas had some political pull. There were only ten camps in total: two in California, one in Idaho, one in Wyoming, one in Colorado, two in Arizona, and the two in Arkansas. Obviously, if you build a camp for some twelve thousand people, that’s a lot of money. Somebody has to build it, somebody has to guard it, somebody has to service it with food and God only knows what, to keep twelve thousand people going. I think it must have been good business, running those camps.

After the war, we ended up back in California. The biggest problem for the Japanese, coming back from the camps, was finding work. There were still a lot of hard feelings toward us. The one job that a lot of people gravitated toward was landscape gardening. It was a very good business, because you could be your own boss.

My uncle was lucky. In 1942, when we were detained, an American friend of his had assumed power of attorney and watched the property. A lot of people got screwed that way; their representatives would sell their property and take the money. But in this case, the guy was honest, so when my uncle got out of the camp, everything went back to normal.

My parents took over my uncle’s store in 1956 and turned the whole thing into a gift shop. Their customers were other Japanese-Americans. Back then, this neighborhood was totally different. It was a self-contained Japanese community: there was a drugstore, a beauty shop, a barbershop, and one or two little Japanese restaurants. There were a lot of boarding houses, too. Right after the war, when people got out of the camps, they would go to the boarding houses or to the church or the Japanese school down here. They would just live there until they could reestablish themselves. We kept to ourselves, in part due to prejudice. My family used to drive to San Diego or San Francisco, and they wouldn’t even rent a hotel room to us because we were Japanese. It wasn’t like the 1960s — I always gave a lot of credit to the blacks, going to Selma, Alabama, being shot up with a fire hose and the mad dogs and all that — I don’t think I could do that. The Japanese were submissive in the sense that they felt, What good was it going to do trying to turn the rock over if there were just going to be worms there? So they tended to keep to themselves.

At the very beginning, there weren’t a lot of Japanese importers around, so my parents had to travel all the way to Japan to buy the little things we needed for the gift shop. Later on, importers would come to us. This shop has been in our family for over fifty years.

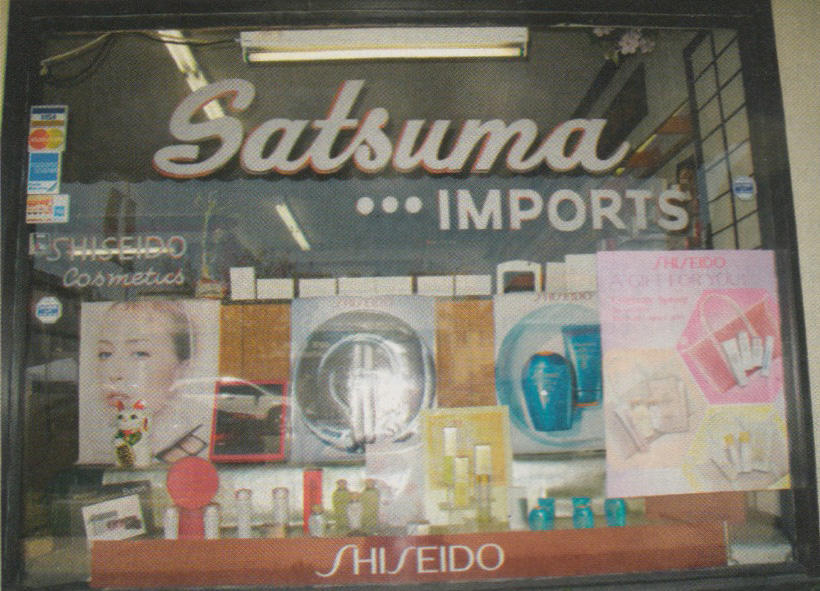

Our little shop was one of the first Shiseido Cosmetics dealers in America. In 1960, my father got a letter from Japan. Someone, a relative or a friend, was on the Japanese ice skating team going to Europe for the Olympics. This person asked if he could meet my father at the airport, just to say hi. So my parents went to the airport and one of the girls on the ice skating team was the granddaughter of the founder of Shiseido. There were a couple of Shiseido salesman along with them, and when they found out that my parents had a gift shop, they wanted to work with them. This was before any department store ever carried it. Americans didn’t even know what it was! But since our customers were mostly Japanese, there were people who recognized the brand from Japan. Shiseido was an old company, around since the 1800s. It had started out as a pharmaceutical company and evolved into skin care and beauty aids.

I started working in the store in 1992 or 1993, when my parents started getting too old to manage things. When I was younger I had been in the Marines, and then had joined the US Army during the Cuban Missile Crisis. I went into a division of the Army called the Army Security Agency, where they taught me Russian and Russian communication. Then, funnily enough, I went to Northern Japan for two years to monitor Russian communications from there. Of course, I knew no Japanese. Then, after seven years in the service, the GI Bill was launched, so when I came back, I went to college. Later I worked for Playtex — that’s a multibillion dollar corporation, you know — and after that worked with American Home Products, where I was the only Asian. When I left, my boss told me they’d taken a chance on me because they’d never hired an Asian before.

Today, the Shiseido still does well for us, as do the vintage clothing and kimonos and these flower vases. Beyond that, we sell a mixture of things, tea sets and sake sets, all made in Japan. We have to carry some stuff from China because of the price, but not too much. Normally Saturday is our best day, sales-wise. Thursday is the worst day because the two restaurants next door are closed. We’ve had famous customers, too. Dustin Hoffman came in, maybe because he was going to the SAG health clinic nearby. He came in twice. He was probably the nicest one we’ve had here, you know, for someone at that level.

We run this place pretty simply. My wife and I are the only employees. We take care of our granddaughter in the back, right there. I don’t need to pay rent; we have no employees. Basically the economy is soft right now, but we’ve seen soft times before and we’ll survive and come back again. This is definitely the worst. When the real estate market was really going hot and heavy, we used to get a call once a week, someone trying to buy the property. But I won’t sell. I tell my two daughters — they don’t want anything to do with the business — when we’re gone, please don’t sell it.

When I started working here full time around 1992, there were three stores in the neighborhood similar to ours. Yamaguchi’s on the corner here, Kabuki on Santa Monica, and Hakata on Washington. Now we’re the last of our kind. Our commitment to the neighborhood goes beyond our little store — it’s also to the Buddhist church, the Methodist church, the older Japanese people who still live in the neighborhood. We definitely fill a niche, so theoretically we shouldn’t be struggling. When you’re still having problems, you know it must be the economy. It’s just one of those things. A lull. It will come back, and we’ll be right there again.