I’ve been trying to sell a book I wrote about a psychiatrist who heads up the Chemical Dependency Outpatient Program at Bellevue Hospital. I had organized the material as a collection of stories she’d told me, along with accounts of conversations she’d had with colleagues and patients; or, as they are called in an American hospital setting, “clients.”

I had no particular attraction to the subject of addiction. It was the nature of the doctor’s interest in what one of her colleagues defined as “the most disenfranchised section of the population” that drew me to her, and her way of turning every encounter and experience into a fable. That, along with her utter disinterest in writing — or in reading, for that matter — made me think that I might in some way make myself complementary to her. What she needed, I decided, was a writer. Or perhaps she decided, because when we first met, she spoke for almost four hours. At the time I was in need of a story to tell.

When I’d finished, I handed in the manuscript to my agent and left on a weeklong trip. By the time I returned, there were seven messages: I was to call right away. I could sense his excitement. One message read, “I like that the shape of your narrative follows the pattern of her clothes, stitched from many beautiful and distinct garments. The stories layer and drape quite wonderfully to each other, so that in the end you’ve delivered one rich and marvelous garment.” There was talk of movie rights. My agent wrote a note to one editor saying he thought the appeal of the book was “deep,” and that the fact that it was as yet “unreported” made it all the more appealing.

The story began with an account of why it was that the psychiatrist wore a horn in her lobe. She was a woman of some beauty, thin and of compelling elegance despite, or perhaps because of, the combination of hand-me-downs she wore and the strings of beads around her neck, including one made of human teeth recovered from a cemetery in her mother’s isolated hometown of Ftan, in Switzerland, only half an hour’s drive from St. Moritz but several worlds away.

It was suggested to me that the horn appeared too early in the story.

If in person my subject might have repelled the prospective reader, she might also do so at the start of a book. The Swiss artist Not Vital, who is the psychiatrist’s closest friend, told me over dinner to be careful she didn’t come across as too strange.

That was indeed a problem I grappled with, for my subject did seem strange, thanks to the horn, a curved and hollow black chamois horn from the Swiss Alps. Her dazzling smile, which Vital likened to the toothy maw of a wheat thresher, didn’t help either. Even more disquieting was her “lack of boundaries” where patients were concerned.

The verdict was in: strangeness should remain within bounds. Salability demanded that my reader be much like an addict — strung along, with small doses, desperate for more. For the first time in my life, I began to take Frank Capra’s maxim to heart — you can’t sell anything to the American people that isn’t entertainment. So from a book that could be read at leisure, I aimed to extract a book that would hold the attention. I had to find a string that would pull this ideal reader in and through to the end of the yarn.

As I looked through the many chapters I’d written, I discovered that there might indeed be an addictive thread running through them. Perhaps the book wanted to be a salable book after all, instead of a lovely shelf of stories there for you to take or leave, this year or ten years from now, or never. That’s how I tend to consume a book — in small bites, stopping for tea, with other books, other rooms, intervening.

I had a chapter that two people agreed could go to the front of the book. It told a great deal about the psychiatrist, how she had discovered that one of the hospital’s most senior physicians was an alcoholic, and how she had confronted him only a few weeks into her new job. At the end of the chapter, the psychiatrist led some of her patients onto an abandoned lot by the hospital, where together they began to plant what would become the first garden at Bellevue. The lot was surrounded by a cacophony of architectural styles, from late Victorian brick to ’60s brutalist concrete, and the hospital wanted to turn her sculpture garden into a parking lot. If the reader could be made to worry about the fate of the garden — and of the psychiatrist, too, since she desperately needed to keep tending the garden for and with her patients — then the book would have its hook. I knew that the garden had already been saved; it had happened around the time that I settled down to write the book. But I had to keep that from the reader till the last chapter. A young documentary film editor whose advice I sought thought that this, like the horn, was a “reveal.”

The editor who’d published my previous books wrote me an affectionate note, saying, “It is so hard to sell anything now, unless it’s a book about extreme running or a page-turning thriller, that I think it’s better to make the narrative accessible.” He urged me to “grab the reader by the balls right at the start.” I considered how best to do this. Oddly enough, the chapter on the doctor who drank contained a description of how an alcoholic’s testicles shrank; only after I’d placed that chapter at the front, sleepwalkingly following instructions, did I notice the coincidence. Balls safely ensconced at the start of my crypto-bestseller, I decided it was time to take a day off. Smoke was coming out the top of my head from transposing parts of the book from one end to the other, trying to recall whether a certain dog had already been mentioned by the time it managed to infiltrate the hospital’s security system. Was the psychiatrist’s discussion of the furniture she had built with her own hands appearing after her wrathful boyfriend had flung that very furniture — a cupboard, a settee, several chairs — out the window? Problems of continuity, as film people say. I repaired to Canal Street.

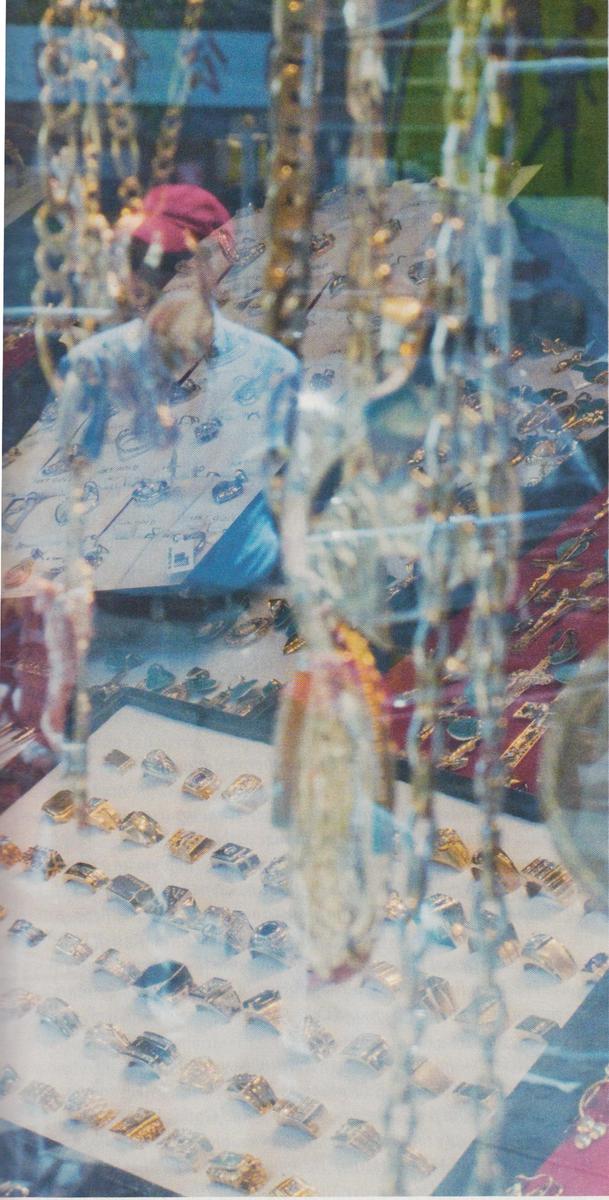

It was raining as hard as in Kurosawa’s Rashomon, and raining hard in my soul, too, as in Valéry’s poem. How was business on Canal Street? There were little men sandwiched between large yellow and red signs that read, “WE BUY GOLD,” walking up and down before the various entrances to the various malls. Two objects caught my eye: a Virgin of Guadalupe in platinum, gold, and diamonds, for $9,700; and a glittery globe clasped by a pair of hands with the legend “WORLD IS MINE,” for $12,900. In the facing window was a pendant depicting a small robber made of solid gold and covered in diamonds. He was modeled on the Pillsbury Doughboy, and he held a bag — of loot, presumably, which he clinched at the neck with one gloved hand. The Virgin of Guadalupe sold better than anything else in the store, I was told. She was doubly attractive — blessing whatever sort of business might bring in enough money to buy one of these homages to her, and protecting it from possible nefarious consequences (shakedown, double-cross, jail, etc.).

Just as I entered the mall and noticed that several shops were shuttered, including one called Bling, my cellphone rang. It was a journalist friend who’d written a book about a designer. She’d handed in her text and been paid too little for it three years earlier. Now the editor wanted five thousand more words, and she was “pissed, Kitty.” (She always called her girlfriends Kitty, after Kitty Foyle in the film with Ginger Rogers.) That morning a Mademoiselle Laporte had written to me asking that I send her an authentic tax certificate: a document from the IRS stating that I paid my taxes here. No, the front page of my tax returns wouldn’t do; I’d need a W-9 form, and I’d have to send the original by mail. They had $100 they owed me for republishing an article I’d written about an Ethiopian actress, model, and activist. For another magazine, I recently interviewed the woman who’d made a great deal of money in the 1980s writing How to Make Love to a Man and other bestsellers, then lost it all to Bernie Madoff. Her loss was my gain. Her loss was a gain for her, too, when she wrote a bestseller about losing her savings at the end of her career.

Years ago, a janitor in a building had looked at me in utter amazement, asking: “They send you on a trip and then they pay you for it, really?” They did. They still do, only now everything takes longer. They send me, then they wait. I write, then I wait. I went to Dublin recently. I could take my time writing the story: I could move the pen slowly, as though through water. That’s why I want to sell this book. Grab them by the balls. Buy a Virgin of Guadalupe or a “WORLD IS MINE” globe so the Chinese lady who works at the store on Canal Street can go on holiday with her Vietnamese husband and read my book on the plane, never putting it down.