Not so long ago, most maps of the world used the Mercator projection, which unpeeled the planet’s rounded surface and rolled it out, like dough, into a neat rectangle. This stretched the higher latitudes and squeezed tropical zones, so that Alaska seemed to outsize Brazil, and Sweden to equal India.

The standard wall-chart versions in the American schools I went to skewed things further. Snipping the great landmass of Eurasia in two along a line running roughly from Calcutta to Yakutsk, they rendered the world as a sort of triptych, with a plump United States flanked by a rump Europe and an amputated Asia. In that smug world, lucky northern folks occupied the roomy upper reaches, lorded over by an American Middle Kingdom, while southerners huddled in the space below.

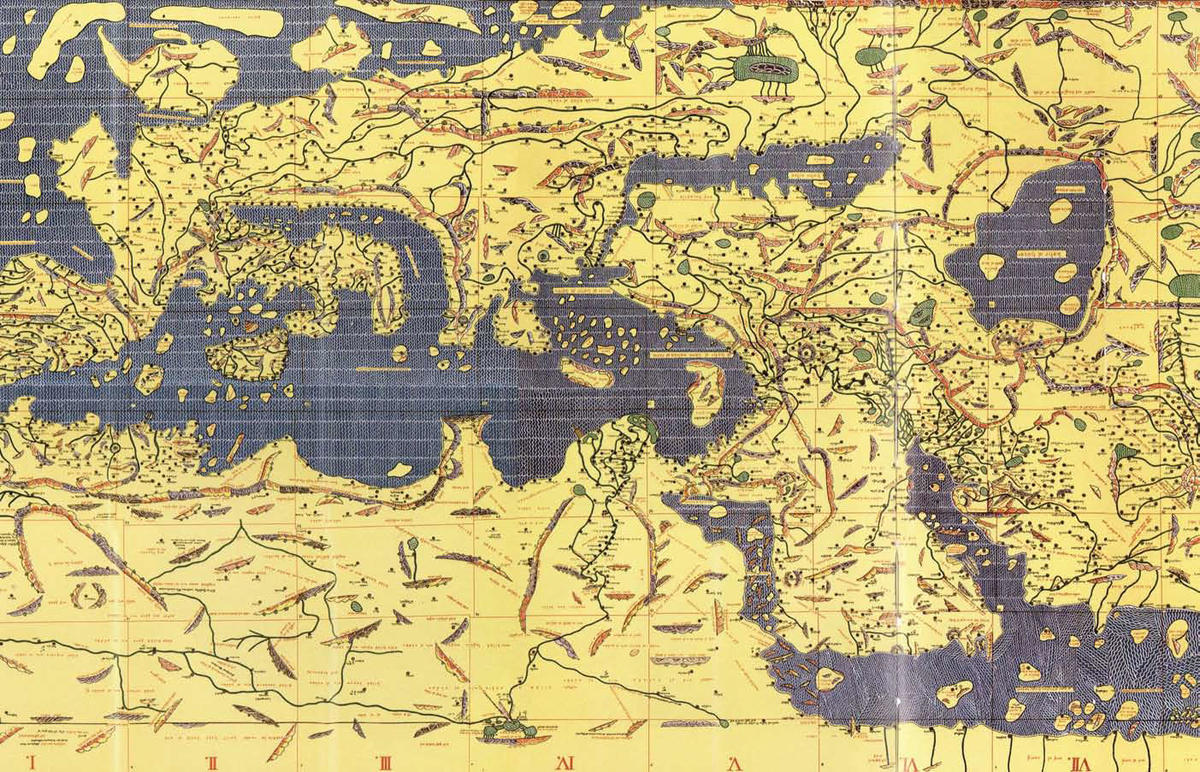

So it was mildly unsettling to find this world turned upside down in the large framed map that I encountered in an Iraqi dissident’s office in Kuwait, shortly before the American invasion of his country. It showed the most populous quadrant of the globe, the northern part of the Eastern Hemisphere, with Africa curled along the top, an ungainly Italy seeming to pour out Europe onto the bottom, and a smattering of islands to the left representing the East Indies and, perhaps, Japan. Squiggles of Arabic identified both familiar places, such as Damascus and Rome, as well as a mysterious “land of the Waqwaq” near what is now Mozambique, and the gates of Gog and Magog down in the bottom left, in distant Siberia. The navel of this world, where those old, now disgraced, American maps placed Washington, DC, was somewhere between Baghdad and Mecca.

A label said that this was a reproduction, printed in 1956 by the Iraq Geological Survey, of the mappa mundi created in 1154 by the Moroccan geographer Abu Abdallah ibn Idrisi. My dissident friend explained that it was one of the few things he still possessed from Iraq and that he treasured it because it evoked not only an Arab-centric world but also the proud, prosperous Baghdad of his youth, where a government agency had taken the time to revise and reprint this greatest and most accurate of medieval maps. (The dissident hated Saddam Hussein but thought America’s invasion plan monstrous and liable to unleash “a thousand Saddam Husseins.”)

On further investigation, I learned that Idrisi’s mapping project had been sponsored, not by some illustrious sultan, but by the Norman king of Sicily, Roger II. Despite the fact that his capital, Palermo, had only been wrested from Muslim control a few decades before, and in spite of the ongoing crusades in Palestine, Roger was good to his minority subjects, including Orthodox Greeks and Jews, as well as Muslims. So keen was this enlightened ruler to understand the world that he commanded the compilation of a general geographic encyclopedia. Most scientific knowledge at the time happened to be in Arabic, so it was natural that he should invite Idrisi, a scholar known for his wide travels, as well as for his scientific work in the madrassas of Andalusia, to his court.

The team, headed by Idrisi, labored for fifteen years, resulting in the production, only days before King Roger’s death, of a great book titled Nuzhat al Mushtaq fi Ikhtiraq al Afaq (Delight for the Seeker of Breaching the Horizons). The text was also known more simply as, The Book of Roger. It comprised detailed descriptions of all known lands on what was described, quite categorically, as a spherical globe. The accompanying atlas used different colors and symbols to mark lands, seas, rivers, lakes, mountains, and cities. It included seventy maps, with ten plates accorded to each of seven climate zones between the equator and the North Pole. The Baghdad edition I saw reconstructed this atlas as a single sheet.

Less than a decade after King Roger’s death, an uprising of Sicilian barons, instigated by the pope and partly inspired by resentment at Roger’s openness to Muslims, led to the sacking of his court at Palermo. Idrisi himself is believed to have fled home to Morocco. All Latin versions of his book were destroyed, leaving only a rare few Arabic copies. Most tragically, an object that King Roger had considered his geographer’s masterwork, a silver disk or globe that was said to have measured two meters in diameter and been exquisitely engraved with a detailed map of the known half of the world, vanished.