Dearborn

In/Visible: Contemporary Art by Arab American Artists

Arab American National Museum

May 19–October 30, 2005

In/Visible: Contemporary Art by Arab American Artists opened in late May at the new Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. Though the small gallery space is cramped, guest curator Salwa Mikdadi successfully broaches a huge subject — Arab-American art since the 1960s — with a sophisticated and selective eye. Discussions of “tradition,” an all-too-pervasive theme in exhibitions of this sort, thankfully take a backseat to a more interesting focus on the work’s shared political, cultural and aesthetic strands. And though such a project could easily devolve into packaged nostalgia or excessive political commentary, the picture that emerges is instead one that revels in its own ambiguities.

The multilayered approach of In/Visible counterbalances the museum’s devotion to multiculturalist rhetoric in its permanent galleries, which convey a mostly patriotic and celebratory image of Arab America. Though some might argue that such a safe road is a necessary starting point for public displays of “marginalized” group identity, the museum is too extreme in its caution, forgoing complex messages and discussions for the sake of streamlined displays and easy-to-consume sound bites. In/Visible (and the two day symposium that accompanied its opening) seems nothing less than avant-garde in such a setting, and the effect leaves the visitor questioning whether visual art is the only medium through which boundaries can be pushed and new grounds can be broken.

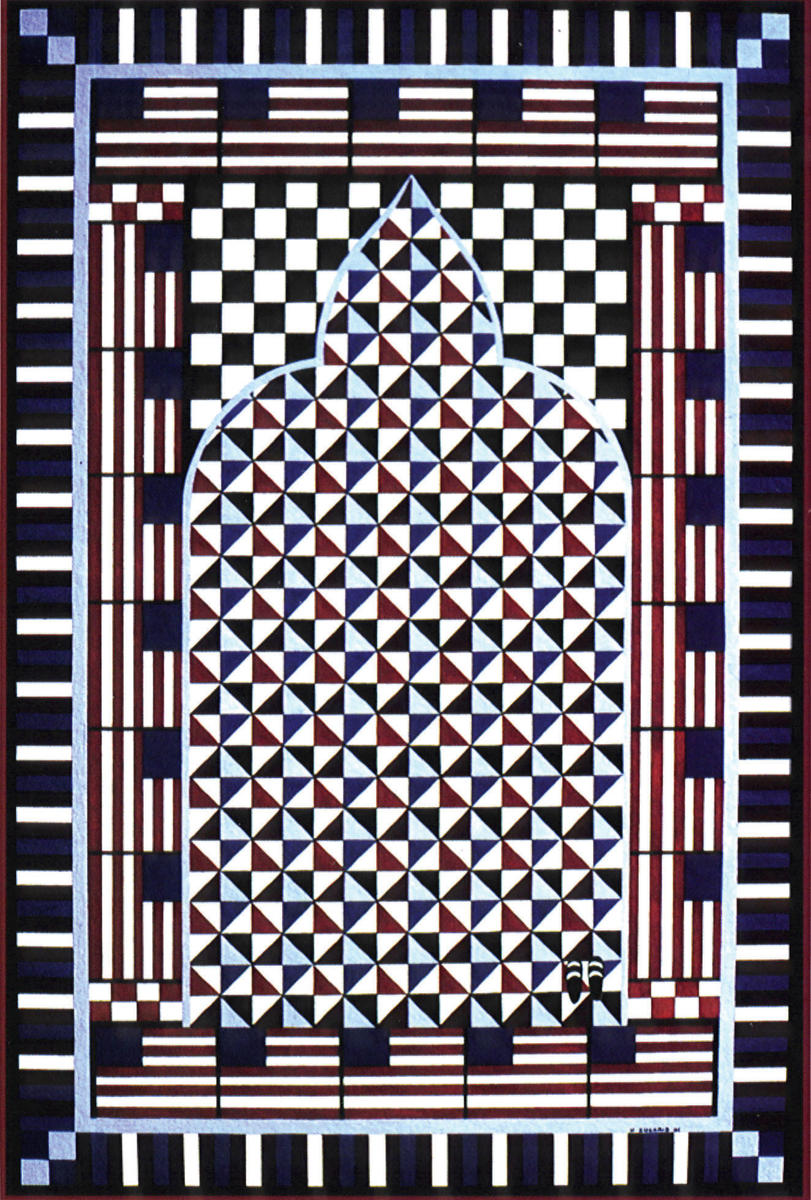

In/Visible features fourteen prominent Arab-American artists whose work spans a broad range of media and formats, from the large canvas panels of John Halaka’s A Path of Least Resistance (1999–2000), to the mixed-media (website, video, postcard) installation of Mariam Ghani’s Points of Proof (2005), to the digitally manipulated photographs of Rheim Alkadhi’s Pictography in Nine Volumes (2005). Some works, especially Helen Zughaib’s Prayer Rug for America (2001), a giclee depicting a prayer rug comprising different geometric American flag motifs, are overtly cheerful fusions of America and the Arab/Muslim world; others, like Athir Shayota’s Apartment 63 (2004), an oil on wood image of a man peering uncomfortably out an ajar door, treat more effectively the misfit of living in a diasporic space.

Indeed this familiar theme of cultural, political, and aesthetic “in-betweenness” is one of the show’s explicit focuses. As Mikdadi writes in the exhibition catalogue: “Examples in this exhibition indicate that in a postmodern world, rigid boundaries and definitions of art dissolve and give way to hybridizations that occupy interstitial spaces.” The artistic atmosphere that results from these post-modern breakdowns is one that spawns cross-cultural borrowing or, to use a phrase from the catalogue, the “cross-fertilization” of ideas and images.

While many of the works in In/Visible do consider the new identities that emerge from an increasingly boundless international space, others address the dispiriting political realities of a undeniably bordered world. Abdelali Dahrouch’s Crossing (2005), for example, superimposes almost invisible newspaper type from reports of illegal border crossings depicting lushly colored backgrounds; desert (the Mexico/U.S. border) and sea (the Morocco/Spain border). The work is part commemoration of the traumas and even deaths that result from border crossings, and part critique of the power imbalances that necessitate such movements. Sumayyah Samaha similarly probes the force of borders in Israel/Palestine Fence, In Memory of Edward Said (2003–4), which protests the ongoing construction of the Israeli wall. The torn sheets of paper, covered with blotchy watercolor and blurred ink passages of Arabic poetry, are tenuously held together to represent both the fragile poverty and hopeful strength of Palestinians living under occupation. Dahrouch, Samaha, and others remind us that rather than the world becoming one, big, free-flowing whole, border surveillance grows more hyper-vigilant by the day.

For cultural and national borders, as Mikadi emphasizes in the catalogue, persist for many Arab-American artists, fostering visibility in some contexts and precluding it in others. It is not surprising, for example, that the original version of Zughaib’s Prayer Rug for America can be found hanging in the Library of Congress, while other works, notably Emily Jacir’s Sexy Semite (2000–2002) are deemed “terrorist” by some critics (see Bidoun 3, news). One is forced to wonder if In/Visible’s perch is in some ways determined by the politics of difference that fuel exhibitions which focus on “Arab-American art” rather than art that happens to have been created by Arab Americans. Though perhaps the cultural, political and/or national identity of the artist can never be divorced from the art itself, it remains to be seen how long it will take for these works to be displayed without their Arab-American qualifiers.