The Master of the Demon Castle:

Revere the Honorable Mei Shigenobu, superior leader of the Arab nations! Exterminate demonic Jews and the American Empire!

On November 29, 1987, a North Korean woman named Kim Hyun Hee destroyed a Korean Air flight with a time bomb left in an overhead compartment, killing all 115 people on board. When she and her terror partner were caught in Bahrain using fake passports, they bit into cyanide-laced cigarettes. Kim survived, and was transferred to South Korea. We heard a lot about her story in Japan, not least because she’d been masquerading as a Japanese national. She had studied Japanese language and culture at a training camp outside Pyongyang, taught by a Japanese woman who had been kidnapped by North Koreans for just such a purpose. When images of Kim’s face began to flood TV screens across the country, talk shows were inundated with letters from viewers. The letters were mostly from men, and they weren’t outraged or demanding justice; most expressed a desire to “reeducate” Kim by marrying her. My mom, a feminist, responded with anguished sarcasm: Men will spare even a mass murderer’s life, if she is hot!

Kim was given the death sentence in 1989. The following year, she was pardoned by the South Korean government. After her reprieve, she got married, found Jesus, had a baby boy, and is reportedly living happily ever after.

Anonymous23:

Mei, my life!

In April 2001, Mei Shigenobu set foot in Japan for the first time. The daughter of an unnamed Palestinian militant and one of the most wanted terrorists in Japanese history, Mei cut an iconic figure. She had long brown hair, soft features, a milky complexion, and an ample bust. Her face beamed out of TV screens across the country, setting off heated exchanges in chat rooms across the Internet. As with the media sensation over Kim, the discussion focused less on Mei’s mother Fusako, once known as the “Red Queen of Terrorism,” or the details of her stateless life abroad, but rather on her hotness.

Anonymous23:

I mean… more beautiful than any actresses… can’t believe it…Don’t be brainwashed!:

Don’t let Asahi control you! I firmly object to TV Asahi who glorifies terrorists! I had to switch the channel because I was afraid that I would sympathize with her if I kept watching the show!Report from Anonymous:

She’ll probably strip by 30. Japanese talent scouts won’t leave her alone.(no name):

But she is Red.Anonymous23:

But she is smart. She doesn’t do terrorism.

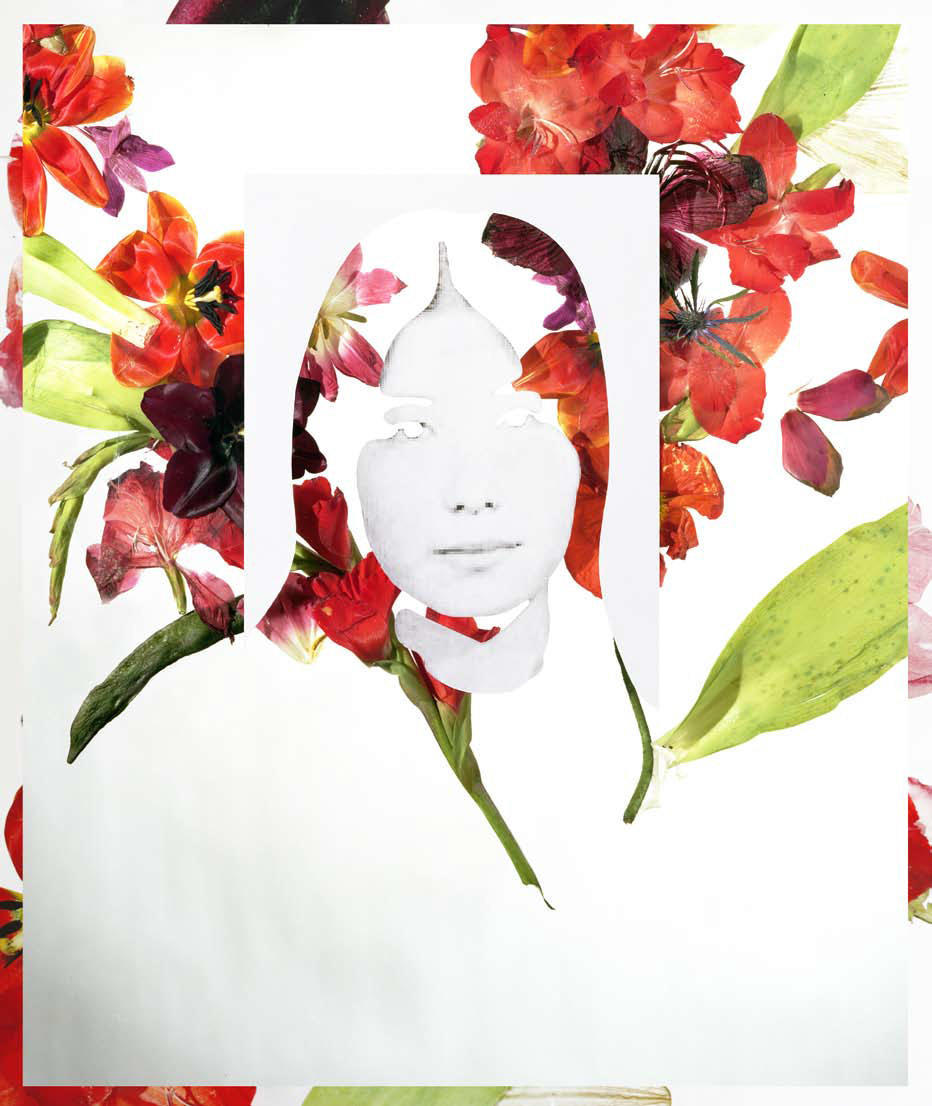

Mei has never been found to be involved in the Red Army’s activities. Still, in interview after interview, she is fully supportive of the cause, convinced her mother can do no—indeed, never did any—wrong. Yet media coverage only ever seems to mention her intimate connection to Japan’s most indiscriminate terrorist organization as a thrilling fact—a spicy biographical analogue to her exotic looks. Apparently the Japanese have a weakness for dangerous beauties. Even at the height of the Red Army’s terror campaign in the early 1970s, Fusako Shigenobu was praised as a rare flower. Today the website dedicated to supporting her fight against imperialism features photos from her youthful days, promoting the seemingly widespread belief—or hope?—that no one so beautiful could possibly commit the atrocities she is accused of.

(no name):

So back then they wanted a simultaneous global Communist revolution of some sort, see.

Among the items on display on Fusako Shigenobu’s blog, The Bulletin of the Olive Trees, there are photos, news items, and poems. There are haiku about the anniversary of her arrest, about her father, about a cold morning in her jail cell. There is also an MP3 of a song she managed to write, record, and upload, entitled “For Japanese Revolutionaries”:

In the midst of a battle

We were brought up

Do not fear betrayal, incarceration

March on, march on, freedom warriors

We are the sons and daughters of the comrades

It is an oddly childish song, as though Fusako herself were not a comrade whose actions more often than not entailed the death of innocents. As though she were, in effect, her own daughter. Fusako remains close to Mei, and to her two adopted children. (When the three children’s names are combined in a certain way, the resulting characters spell “victory of revolution.”) Not long after her arrest, Fusako published a book, her sixth, in the form of a letter to Mei: I Decided to Give Birth to You Under the Apple Tree (2001).

Fusako Shigenobu founded the Japanese Red Army (JRA) in 1971. It is not to be confused with the Communist League–Red Army Faction, the late-1960s radical student group whose members (including the bass player of the visionary Japanese noise band Les Rallizes Dénudés) hijacked a Japan Airlines flight in March 1970 with samurai swords and a bomb. Nor is the JRA the same as the United Red Army, a paramilitary ultra-leftist group as infamous for murdering its own comrades as for its major terrorist operations, a robbery at a gun shop and a hostage-taking at a ski lodge. But the JRA was related to both groups, as indeed it was related to the Red Army Faction of Germany and the Red Brigades of Italy, and, especially, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).

The Japanese Red Army was actually based in Beirut, Lebanon, where Fusako and her crew had journeyed in 1971. Like other aspiring radicals at the time, Fusako was inspired by the dramatic successes of the Palestinian movement, especially the PFLP, which had inaugurated the era of international terrorism in 1968 with the hijacking of an El Al jet. The JRA would learn from and collaborate with the Palestinians in their struggle against the Zionist entity, while building up a revolutionary base from which, one day, they would return to Japan and lead the student left in overthrowing capitalism and the monarchy.

Over the next two decades, there would be hijackings and hostage-takings in Dubai, Kuala Lumpur, Dhaka, Jakarta, Manila, Rome, and Naples, among other places. There was the occupation of the French Embassy in The Hague in 1974, an operation that netted the JRA $300,000 and the release of a captured comrade, and for which Fusako was ultimately convicted. The group’s most notorious action was the 1972 assault on Lod Airport in Tel Aviv. Three JRA members opened fire on a baggage carousel, killing twenty-four people and injuring seventy-eight more. The name Mei translates from Japanese as “life,” but the daughter Fusako bore in 1973 was named after the English word for the month of the Lod attack. (Indeed, her name is sometimes given as May.)

Fusako was arrested in 2000 near Osaka, Japan, shortly after her secret return to the country of her birth. She officially disbanded the JRA from her jail cell, though the group had been moribund for years—the passing of the Soviet Union and the other Eastern European communist states in 1989 had wiped out the last vestiges of a support network that had sustained groups like the JRA, while the rise of Islamist tendencies in the Palestinian national movement and the signing of the Oslo Accords further undermined the JRA’s ideological position. From her jail cell, Fusako has written books about her life and Palestine and maintained her blog, full of hope and idealism in the face of oppression by her old enemy, the Japanese state. A book of her haiku, Jasmine on the Muzzle, appeared in 2005.

Anonymous-San@My Belly is Full:

I don’t care, just let me fuck her!

Mei Shigenobu is now a media celebrity. She hosts a news program on TV Asahi, one of Japan’s largest networks. She has written two books, including From the Ghettos of the Middle East (2003) and Secrets: From Palestine to the Country of Cherry Trees, Twenty-Eight Years with My Mother (2002), the latter an account of her life growing up without a nationality in and around Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. And she has become a kind of muse for aspiring radicals, as well as some members of the older generation, for whom her mother once played a similar role. Needless to say, she is involved in the Free Fusako Shigenobu Committee, though its efforts have not thus far had the desired effect. (Fusako is nine years into her twenty-year sentence; she will be seventy-five when she is released.) She is, in her own way, an incredibly effective spokesperson for the Palestinian cause, which has led to protests from at the Israeli Embassy. Of Japan she observes, “I always felt I should be here. I’d never been before, but always felt I belonged. I think it must be the same feeling that young Palestinians who have grown up in camps have about their own homeland.”

Mei’s most remarkable role in her new Japanese life is her star turn in director Nobuyuki Oura’s “avant-garde documentary” 9.11-8.15 Nippon Suicide Pact (2005). A philosophical road movie and journey into the visual and political history of twentieth-century Japan, the film stars Ichiro Hariu, a seventy-something leftist critic of literature and art, and Mei Shigenobu, who is described by the director as “an embodiment of the past and the future, dream and reality, nihility and hope, discontinuity and solidarity.” In one scene, Mei visits the home of Chi-Ha Kim, a South Korean poet, philosopher, and democratic activist. Mei tells him that her name means “life” in Japanese. She explains that she was exposed to many wars growing up—the Lebanese civil wars and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict—and that the experience taught her to respect the lives of everyone she encounters. Kim says he identifies with Mei as a fellow global citizen, that the meaning of her name resonates with him. He says he has a hunch that Mei will contribute immensely to world peace in years to come. In the 1970s, Kim was imprisoned for seven years and routinely tortured by the South Korean government for his advocacy of democracy; so perhaps his intuition is worth considering.

In a YouTube clip related to the film, Mei talks about her experience acting in Suicide Pact. At the time of the interview, she was thirty-four years old, and right away one thing is clear: she is hot. As her various media images testify, she is charming and articulate, “one of us,” if not a better person than most of us. As her writings testify, she is knowledgeable, down to earth, and compassionate. What seems eerie—to me, at least—is the interview’s complete normalcy. In Mei’s world, her mother never killed anyone, never conspired to kill anyone; she is not contrite, because she is innocent. And based on the interviewer’s tone of voice, it wouldn’t be surprising if he turned out to be Anonymous23 from the chat room. Mei seems to respond to his flirtation, which in turn is directed to the viewer. She is talking about how she always wanted to be an actress, how she has finally managed to step out of her famous mother’s shadow. Dreams that any girl would entertain. Lightness surrounds her. In this lightness, unburdened by the trail of dead bodies her mother left behind, Mei Shigenobu bobs from screen to screen, her hot face shining through each one.