One afternoon, Jill Magid, small, pale, black-haired, walked into the headquarters of the Amsterdam police and offered them a project. She told them she wanted to do an art piece about their surveillance cameras. The Dutch policeman at the front desk was unimpressed. He passed her off to someone on the phone. “We don’t work with artists; we’re a police station,” he said, and that might have been that — for someone other than Magid.

Instead, the rejection hooked her. There’s nothing more enticing than an absolute no for an artist whose work is as much about the process of penetrating closed systems, stitching vulnerability into icons of security, as it is about the product she ends up with.

Back in her flat, she researched the history of the Amsterdam police and found that they were tuned to the power of aesthetics, that they’d even won an award for the design of their cop cars. So instead of approaching them as an artist, she came back as the consummate contemporary businesswoman — Jill Magid, consultant. She curated a portfolio of fancy surveillance cameras, donned a business suit, and presented the police with her new business card: Jill Magid, System Azure Security Ornamentation Professional.

A conversation began. The police weren’t sure they wanted to advertise their surveillance cameras. But weren’t they supposed to be a deterrent? she offered. She flattered them with their own self-image, how they cared about their relationship with the public and cared about aesthetic appeal. Why not ornament their surveillance cameras? After several months of negotiation, they hired her. She began climbing ladders in Amsterdam and adorning those cold surveillance machines with cowboy kitsch, rhinestones color-coded for police ethics — green for justice, red for “full of love,” blue for strictness, and white for integrity.

But is that art, you might ask? Rhinestone-studded surveillance cameras? Not really. For Magid, the art is the process of getting intimate with systems, of subverting technology into sensuality, seduction, a love affair. On the System Azure website, she documents all her encounters with the police; the process of seduction is her art.

Magid first began “intimatizing” power and public space in New York. Recently out of college, she began photographing spaces between buildings, shadow-spaces in old piers, drawing soft architectural models and sewing bubbles into urban parentheses. Later, when she got to MIT’s art and public space program, her teachers suggested that without millions to build the huge structures she was imagining, she ought to distill her ideas into an essence. Her “kiss mask” embodied that sensualizing project. It’s made out of wire from heating ducts and meshed fabric. It forces kissers to gaze as if in a mirror at their partner in the same mask. (It looks like kids in pretty gas masks trying to smooch.)

Magid wanted to film the space inside the masks in order to document the kiss, and it was then that she discovered spy products. For $179 she could order a lipstick spy camera. She knows that most artists working on surveillance started with a political notion. But for her, it was what she refers to simply as “feeling” that brought her to technology. The feeling of wanting to bring the hyperworld down to the fingerworld. To wrap the Empire State building or the Reichstag in flesh, or create a kiss out of industrial debris.

“I seduce systems of power to make them work with me,” she says. It would be easy to engage that system with the snide superiority of the urban artist, making easy political statements, mocking the battlers of terror and crime. But she was looking for something more. She wanted mutual accountability, an exchange of power and vulnerability. Artist as gift-giver and -receiver.

EVIDENCE LOCKER

Liverpool city center is monitored by 242 surveillance cameras. But is it really guarded?

The cameras film twenty-four hours of real time, then move to time lapse at three frames per second. The footage remains computerized for thirty-one days; after that it cascades off the system and is swept into oblivion — with one exception: If you, fill out a Subject Access Request Form, which tells who you are, where you were, and what you were doing, and then send it along with a little photo of yourself and ten pounds, by law the police have to take the footage of you and store it in an evidence locker for seven years.

Magid entered the Liverpool system as a researcher. She turned her access forms into love letters describing what she was doing, feeling, and thinking and sent them to the police. She got obsessed with the idea of storing her memory in an evidence locker, offering herself as a guinea pig to their system. She’d wear a red trench coat and red boots, and they could track her through the city for thirty-one days.

She played with the trope. She knew they were following her through the city, and she knew where the cameras were. One time she shut her eyes for a minute in a public square. Later the police told her they were nervous watching her do that because they couldn’t protect her. “What I loved about that is they saw the fault in their own system. It’s one-way. They couldn’t help me.”

Things twisted further and further until the borders were broken down. Who was the artist? Whose gaze was on whom? Who was representing whom? Who was the surveiller and who the surveyed? No longer the artist as voyeur, she was the artist as subject of voyeurism. She loved the feeling not only of being followed, not only of seducing systems of power, but of monopolizing the surveillance grid until it ditched its purpose — whatever that was — for an addiction, an obsession, the lady in the red coat.

She taught the police film theory at night. She urged them to film her à la Godard. Imagining herself as Brigitte Bardot, she told them to trace her as if she were indeed BB. Finally, she suggested that they put a microphone in her ear; she’d close her eyes, and they would keep her safe, their voices guiding her through four cameras and eighteen minutes of tape in the city. The piece is called Trust.

The installation of Evidence Locker was shown at the Liverpool Tate and FACT (and many other places). You can enter the locker here: www.evidencelocker.net/story.php. When you register, you’ll receive thirty-one files, every hour or every day, her diary to the police, and a daily surveillance clip of the lady in the red coat on a wet Liverpool street.

WAYS OF SEEING

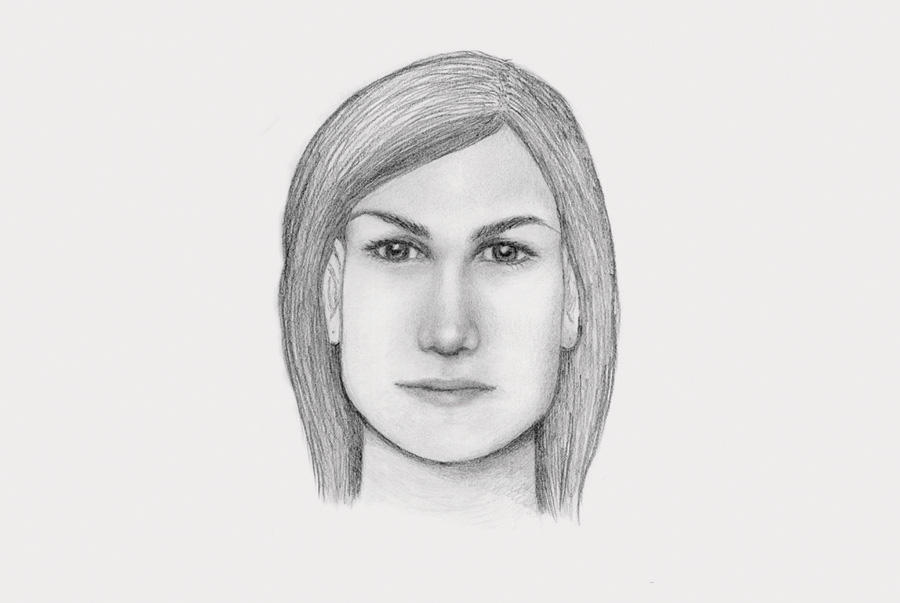

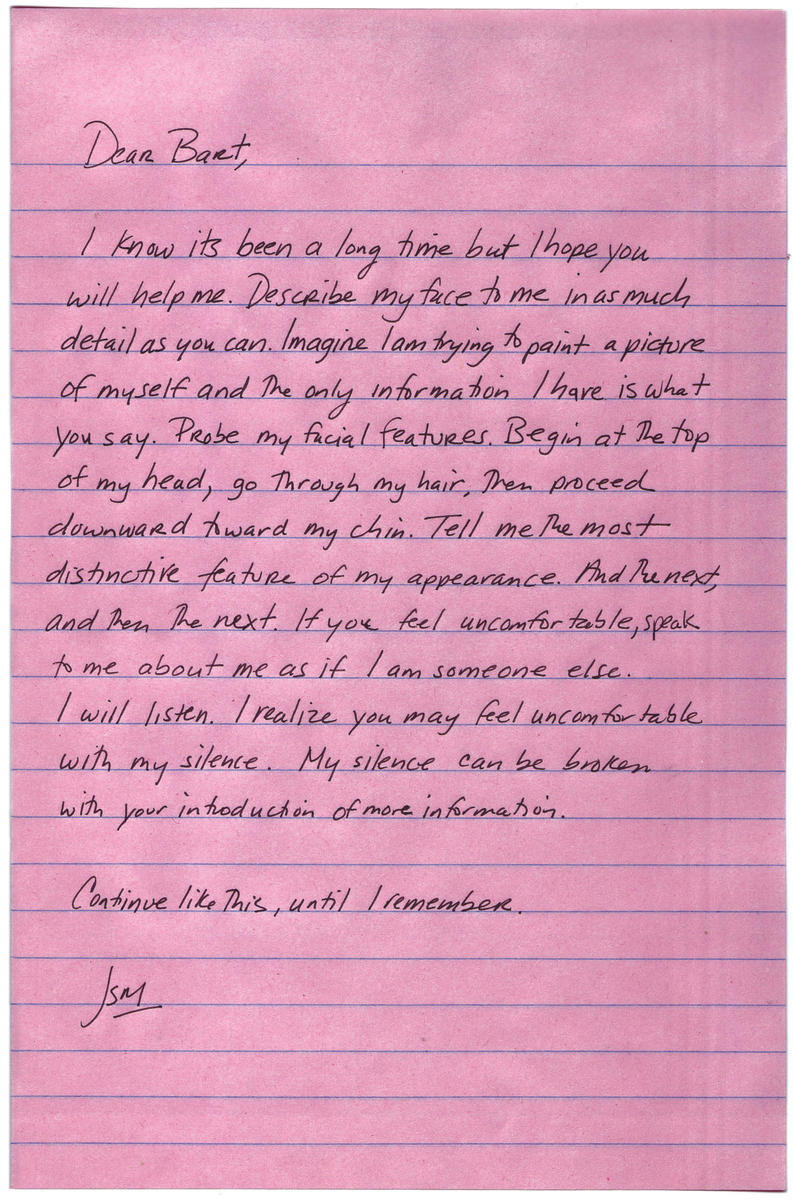

In the Amsterdam police library, Magid came across new methods detectives were using to induce better recall in witnesses. “It almost sounded like a love letter or a sexual manual,” says Magid. Which is in some ways how she reads most potential encounters. In a project she calls Composite, she rewrote the rules of interrogation as into a letter and sent it to all her ex-relationships: “I need you to remember my face.” They’d write back, and she would forward the description to a series of forensic artists, writing, “There is a woman who is absent. I can provide you with her description. Will you help me realize her?” She became a mediator between the forensic artist — who needed more details — and the ex-lovers. “My favorite one went eight times back and forth, and the letters got so beautiful. He said, ‘I can’t remember anymore whether she looks like the drawing or my memory.’ And the more he tried to remember the more he forgot what I looked like” — memory as a way of seeing or failing to see. By handing over the drafting to her lovers and to the forensic artists, Magid evoked a tradition of self-portraiture and documentary. The work became a kind of bildungsroman, a portrait of the artist conceived by her but drawn through the eyes of those who saw her most intimately, with the hand of a complete stranger.

From there it was just a short step to a piece she called Head. She went to the Utrecht hospital, got a catscan of her skull, contacted the number one forensic 3-D modeler, who usually works on murder victims or anthropological subjects. The forensic modeler (named Maja, who never met or saw Magid) was fascinated by the prospect of doing a live skull. She called it “Maja’s Ghost.” Ostensibly playing off of Salvador Dali’s “women in ecstasy” series, Magid got the modeler to make a forensic bust of her in ecstasy. Complete with a hair sample, model skull, a cast of teeth, and fake skin, the head sits on a pedestal alongside a forensic report and conjures the horror film F/X, or Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Theresa.

PLEASE BE ADVISED YOU MAY BE SUBJECT TO SEARCH

The words drop in amidst the New York subway rider’s jostling thoughts, slipping into a kind of surveillance white noise. But for Magid, after many years away from New York, this intercom phrase was an entry point, a way to insert herself into the urban landscape among people she’d come to find familiar — the cops. She needed permission, access.

One day she asked a subway cop to search her. He was taken aback and told her he couldn’t because she was a woman. Then train me, she said. It took a phone call and more encounters, but eventually she convinced him, and for the next four or five months, every night at 10:30pm, she would wait for him to get his assignment and then meet him at the station stop and subway line.

She recorded every detail in photographs, video, voice recordings, even producing a book and installation called, Lincoln Ocean Victor Eddie — those are the police call signs for love. “It became this incredibly intimate story of us at night in these tunnels, and all the beautiful things that happen down there,” she said. More than that, an exchange developed between the working-class cop from Staten Island — who has never left home, reads the tabloid Daily News, supports the war in Iraq (a place he mis-imagines) — and the liberal artist whom he saw at the start as partly to blame for a decaying America. Through recounting their late-night intimate moments, Magid complicated our facile reading of the cop, helped us to identify with him, his dreams, his attitudes.

One night at about 4am, the two were down in the noxious Nostrand Station, the kind of place dead bodies would turn up. Suddenly they were engulfed by birdsong. She was mesmerized. He confided that he loved working there because of those birds; he’d close his eyes and imagine he was somewhere else. From then on, whenever she couldn’t meet him at night, he would call her when the birds began singing.

LOVE LIVES ON. OR DOES IT?

Using video, text, email, and performance to engage with the most alienating forces in urban life, Magid manages to eke out narratives at once coy and connected. Those narratives in turn conjure up and subvert a history of iconic film and opera femme fatales and tragic heroines. The red trench coat astray in Liverpool, the insomniac lonely girl wandering the underground, the lover contemplating her history of intimacy — even as she plays these roles, fully engaged and vulnerable, she’s also an observer and filmmaker directing masculine symbols of power.

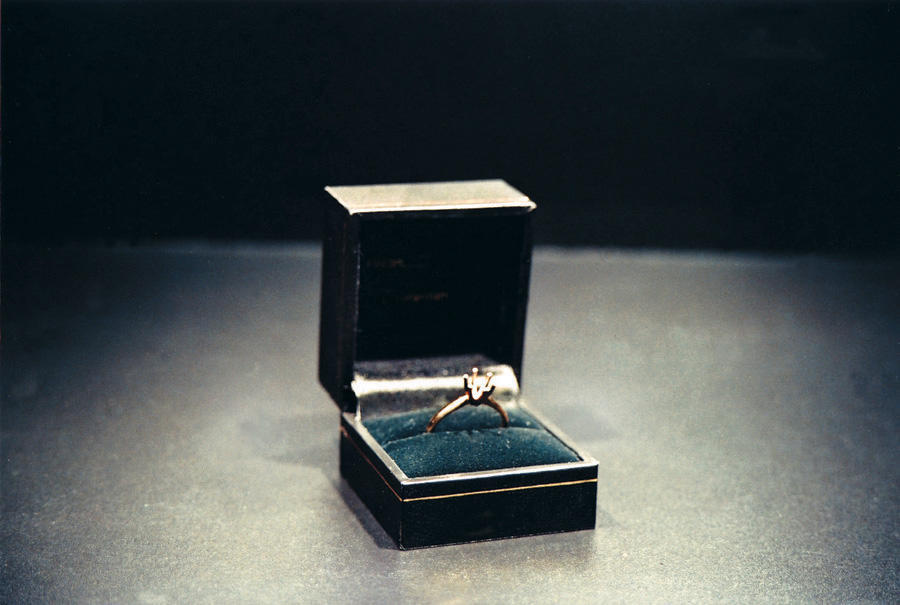

A strange confluence of events led Magid to perhaps her most morbid project. A rumor had long circulated in her family that her grandmother had found a giant diamond ring on the Chicago streets, when she was in her twenties, and then hid it in a safe deposit box for about thirty-five years. When she died, Magid’s family went to the box, and there it was: a 15.2 carat ring. Her parents were terrified. But to Magid, it was an amazing, somewhat tragic portrait of her grandmother. She’d weathered the Depression, a strong, silent woman, and kept this symbol of power and status and security hidden away her entire life. All Magid wanted was to photograph the ring. But her parents sold it off. She lamented the fact. The moment the stone sold was the moment her grandmother really died for her. By the time she tracked it down in the New York diamond district, it’d been ripped out of its setting. “I photographed the diamond and became fascinated with what a diamond means.” Magid’s gallerist at the time told her about a company that will turn your dead body into a diamond. “I looked at the form from the company and realized I had to make a piece with this and realized it should be me.”

Her parents were annoyed; she was over-romanticizing her grandmother’s savings account. She argued that yes, she was, but that’s what her work is about — romanticizing the system. “Some people call me a surveillance artist, but I’m interested in what makes people feel protected and held. A lot of times that’s mixed with power, and diamonds are also mixed with power. It’s also about protection.” Worried about the prohibition that states Jews shouldn’t be cremated, she met with rabbis from every background. Even the most conservative gave her their blessing, declaring that although it’s against Jewish law, the project had launched her on an unprecedented spiritual journey into the meaning of death, and they wouldn’t stand in the way of that. The Hassidic rabbi told her that in their tradition there’s a blessing that your children may become stars. “And this made him think about the body becoming a star or diamond.”

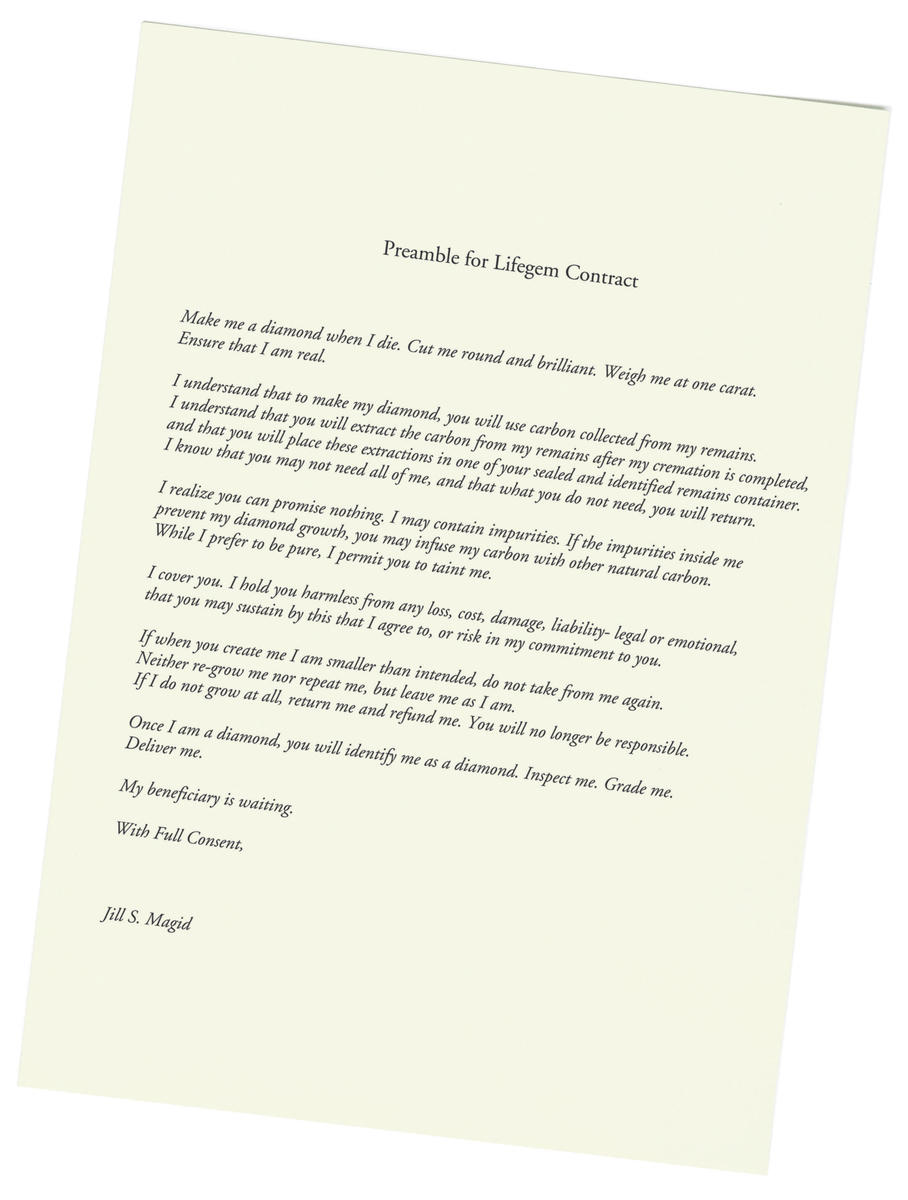

Magid has now made a contract with the company that when she dies she’ll be a one-carat diamond. The piece, called Auto Portrait Pending, is shown as a gold setting (“because of my grandmother”) with an empty one ca-rat diamond. The diamond sits in a black box that’s almost a grave. A standing vitrine shows three documents. One says, “Dear Lifegem, Make me a diamond when I die.” As Magid says, it’s a postmortem marriage with art. There’s a creepy element to all this — once a collector buys the piece, her body is legally no longer her own. “Isn’t that crazy,” she says. “And there’s a collector who wants to buy it.”

THE SEDUCTION OF SECRETS

Back when she was at MIT, Magid spent a lot of time thinking about recognition and identity. She extracted a lot from a New York psychoanalyst named Jessica Benjamin, who wrote The Bonds of Love, a treatise on domination and submission in relationships. “She talks about getting into that intimate space where you lose your own boundaries… you’re so intimately connected with the spaces around you that you feel no separation between you and the other person, and that’s a beautiful space I am always trying to find, and I try to find that with a system that ignores me.”

What could be more indifferent than an impersonal governmental ministry, her latest, still-secret project — or rather, system to be penetrated. The only clues she’s giving out are these excerpts from one of her deepest influences, Polish author Jerzy Kosinski: “Let’s say I’m a protagonist from someone else’s novel.”