Desert Hot Springs is a tiny universe of churches, meth labs, and boutique spas. At its hot and sandy center, closeted in a one-room public library, is a neglected cardboard box, stuffed with newspaper clippings that amount to the local history archive. Many of these snippets, now colored khaki by time, are devoted to a certain Cabot Yerxa, a small man who spawned quite a few tall tales. In the popular fable that recounts the creation of Desert Hot Springs, Yerxa grew so tired of walking fourteen miles every other day for a drink that he eventually dug a hole by hand — forty feet deep under the desert sun — until he struck 140-degree, lithium-rich water. From this hole sprang Desert Hot Springs, the self-described City of Health, originally operated “for the sake of suffering humanity.” The sick and elderly came from around the world to this Fountain of Youth, looking to put some new life back into their old bones. In recent years, though, it’s Hollywood types who’ve been soaking up the most water, wine in hand, for their own leisurely convalescence.

Cabot Yerxa is best known for his eponymous pueblo, which he built in the style of the Hopi Indians. Although the building is a sprawling creation that accreted over twenty-three years (there are 150 windows and sixty-five doors), he built the place to fit his diminutive stature, so it feels somehow miniature. Over the course of decades, wood, nails, poles, and windows were gradually transplanted into Yerxa’s imitation Hopi pueblo from the abandoned settlements of homesteaders who had given up or otherwise deserted their domains.

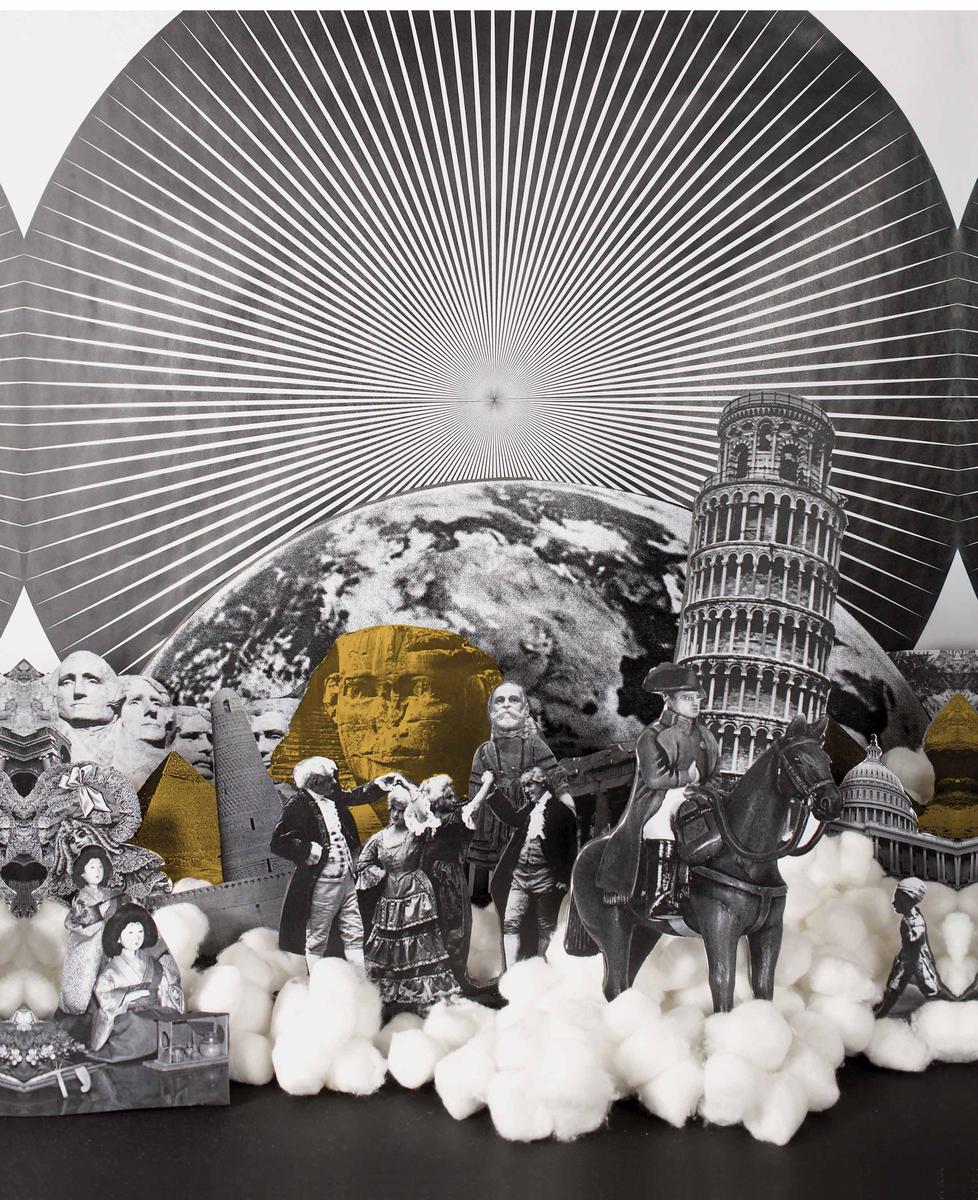

While Yerxa is celebrated in local lore, no one in Desert Hot Springs seems to know anything about his quixotic counterpart, a true miniaturist, Betty Hamilton. Her memory is kept afloat by just one clipping and a few photographs in the library’s cardboard archive. “Kingdom of the Dolls” was Hamilton’s labyrinthine project, a museum of history that packed exhibit upon exhibit into a plain and modest building on Pierson Boulevard. In it, she single-handedly reconstructed the history of civilization, depicting scenes and events as faithfully as she could, all at the scale of eleven-inch dolls.

Although the earliest scenes in the kingdom were a cluster from 2000 to 1000 BC — the Minoan palace at Knossos, ancient Egypt’s Temple of Karnak, and the Wailing Wall — Hamilton began her project with the Palace of Versailles, which was populated with twenty-cent dolls modified to become Marie Antoinette, her ladies-in-waiting, Louis XVI, and courtiers. Over the course of more than twenty years, Hamilton assembled dozens of tableaux, all based on her studies of photographs and artwork, including the beheading of Anne Boleyn; an 1880s San Francisco street scene; a depiction of the Colosseum complete with Romans, Christians, and lions; the fraudulent trial of Mary, Queen of Scots; and a Black Sabbath concert with Tony Iommi collapsed onstage. For some time, Hamilton built and stored the exhibits in her home. But when they grew in size and began to congest the hall-ways, closets, and floors, her husband constructed a building in the front yard that was to be devoted entirely to her passion.

Hundreds of dolls from the five-and-dime were sculpted, painted, and outfitted in the painstakingly detailed period costumes that Hamilton made. She crafted the architecture entirely from discarded odds and ends. The wheels on Napoleon’s coach, for instance, were made from ice cream container lids, and its hubcaps were champagne corks. A partial inventory suggests landfill: paper towel tubes, carpet scraps, coffee grounds, lollypop sticks, split ping-pong balls, an air conditioner filter, garter pins, hair curlers, thumbtacks, a pie tray, and Hamilton’s own hair. But the one photograph of Hamilton standing, beaming, beside her handiwork gives the impression that for her it all came together as a satisfying depiction.

If there’s anything unsettling about the photograph, it might be that the scale of the dolls and their kingdom seems a little too big. Hamilton is almost dwarfed by the miniature San Francisco, and its denizens appear quite capable of insurrection. When compared to the photograph of the exterior of the museum, one can’t help but wonder how many scenes could possibly have fit into the building. The article about “Kingdom of the Dolls” closes with Hamilton saying, “There’s still room in the middle of the floor. But when that’s gone, I don’t know. It’s going to be a terribly sad day when I run out of room.”

Desert Hot Springs is booming now. A wave of development has crashed in from Los Angeles, a hundred miles away, and the open space is being built up into generic suburban homes with rounded corners, volume ceilings, and automatic sprinkler systems. In between the houses are wide roads, transplanted palm trees, and rocks in all the right places. The churches, meth labs, and spas are still around, in the older part of town, and Cabot Yerxa’s pueblo is a historic landmark. But here, on a quiet road bridging old Desert Hot Springs with its new developments, there is a real estate office where Hamilton’s kingdom once stood. “Brand new construction,” reads its placard.