In December of 1985, James Vance and Raymond Belknap, age twenty and eighteen, respectively, shot themselves in the face after many hours of beer drinking and dope smoking in a church parking lot in the town of Sparks, Nevada. In the trial that ensued, the boys’ parents alleged that subliminal messages embedded in the Judas Priest song “Better by You, Better Than Me” had inspired the unevenly successful suicide attempt. (While Belknap died, Vance survived for years, horribly disfigured and addicted to painkillers.) The trial, which began in 1990, went on for five weeks and featured any number of legal innovations, including the appointment of a special “listening expert” and a court-ordered a cappella rendition of the song in question by Judas Priest lead singer Rob Halford (special attention was paid to his pronunciation of the word “me,” or in Halford’s rendition, “meee-yaa”). Five weeks later, the case was thrown out, but not before going down as one of the odder cases in legal history and perhaps the most iconic in a field that has come to be known as “forensic listening.”

Lawrence Abu Hamdan was only five years old when James Vance Vs. Judas Priest took place. Yet the case is emblematic of a series of questions that are pivotal to his practice as an artist. Abu Hamdan, who lives in London, has spent the better part of the last decade thinking about what is at stake when one speaks aloud. Raised between Amman and North Yorkshire, he developed an interest early on in how sound is channeled, received, and rearticulated. He played in his first band at fourteen (punk), and grew fascinated by the ways in which his voice could be manipulated through elaborate and not so elaborate sound systems. He went on to study sound art at university, and subsequent projects have extended his aural investigations, including Model Court, a collaborative work that modeled the spatial and sonic experience of a court room, and Marches, which involved the sonic articulation of choreographed marches through the city of London (marchers were equipped with customized footwear that would squeak).

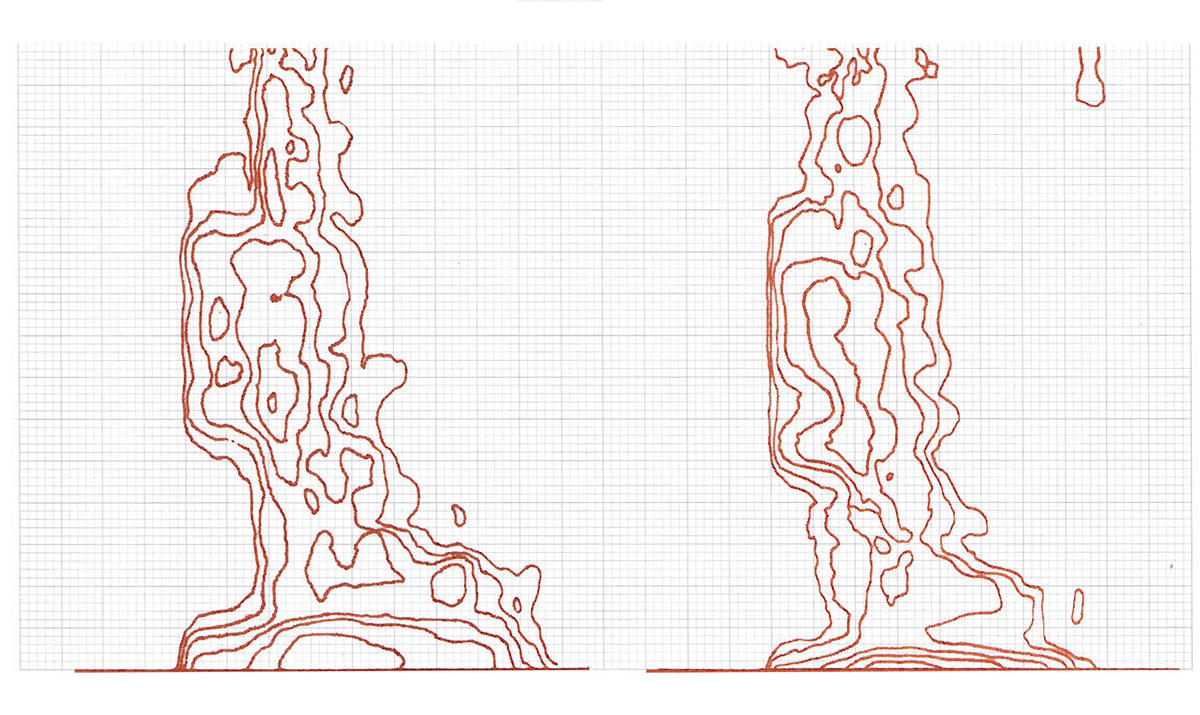

In 2010, Abu Hamdan met with a leading forensic speech analyst named Peter French. Unlike many sound theorists who focus on sound’s ephemeral and immaterial qualities, French’s approach was markedly material. While the dominant school, associated with the likes of scholar Don Ihde, puts forward the impossibility of fundamentally grasping sound, French’s formulation rendered sound dissectable, understandable, even replicable. Spending hours armed with “accent atlases,” listening for the most minute fluctuations in vowels and consonants (running late, layte, lite), you could say he is emblematic of a peculiar form of what various avant-gardes have referred to as “deep listening.” French, who runs a private lab called JP French and Associates, is often seconded in crime cases for a number of duties — from reenacting the sounds of a crime scene (what could have reasonably been heard?) to speech and speaker analysis. He has worked on over 5000 cases since 1984, the year the seminal legislation in the UK known as PACE required all police interview rooms to be equipped with audio recording facilities. Says French of the post-PACE period: “All of a sudden it was as though there had been a thunderstorm and it started raining cassette tapes.”

A series of conversations with French and others resulted in Abu Hamdan’s The Freedom of Speech Itself, an audio documentary listenable at the Showroom in London this past winter. Part Adam Curtis, part John Cage, the 34-minute documentary draws heavily from Abu Hamdan’s evolving archive of sound-related ephemera, but mostly centers around the deployment of forensic speech analysis in asylum and immigration cases. We learn that the practice became widely used in Scandinavian countries in particular starting in the early to mid-1990s in trying to understand an individual’s identity, or in the case of asylum claims, an individual’s credibility. Over time, the practice was privatized, and outsourced to specialist firms with names as creepy as “Sprakab.” Suddenly, science was adopted in the name of politics, and forensic speech analysis joined a cast of unseemly policing methods that also includes the use of iris scanning and thermal emotion sensors.

Of course, like any science, forensic listening is far from fail-proof, and in The Freedom, Abu Hamdan captures its human fallibility, its penchant to be hijacked, and the occasionally disastrous consequences of its use. Peppered throughout the documentary are anecdotes drawn from the artist’s motley research. One hears of a persecuted Afghan man from the Hazara tribe whose asylum claim is denied because of his use of a hard “t,” which convinced analysts that he was not an Afghan at all but a Pakistani. We hear an anecdote about how the word “tomato” was used by Phalangist militias at check points during the Lebanese civil war to detect who was an enemy Palestinian or not (the telltale Palestinian bendooora meant one had to get out of the car and face an uncertain fate). In another memorable case, a Sierra Leonean is mistaken for Nigerian and deported back to “his country.” He wonders aloud as to where he will go once he arrives at the airport in Lagos.

Later, Abu Hamdan interviews an unidentified young man.

So, where are you from?

What do you mean? I’m from Hackney.

Hackney but, you’re Danish right?

No, I’m Palestinian. Well, I grew up in Denmark.

From where in Palestine?

I’m not from Palestine.

So where are you from?

Well, we’re Palestinian from a refugee camp in Lebanon, Ain Al-Helweh.

Okay, so you were born in Lebanon?

No I was born in Dubai.

So how come you have an America accent?

What do you mean?

You have like this American twang to your English…

Well, you know, Eddie Murphy, Stallone and all those guys.

So you’re from Hollywood?

No, I’m from Hackney…

Abu Hamdan conjures a universe which makes little room for the organic collision of cultures, whether born of travel, forced migration, or even television and radio. (How many people do you know who speak perfect BBC-informed English but have never been to England? I know three.) Suddenly, sound has moved from science to politics, with grave legal consequences. We may be free to choose the words we speak, but we do not get to choose the way we are heard.

His sound archive, meanwhile, is growing. From a slapstick scene in Woody Allen’s Bananas in which stenographers obliterate a court statement attesting to Allen’s character, to the use of pitch distorters to disguise witnesses testifying in court during the trial of Saddam Hussein (they made their voices sound like those of children), Abu Hamdan is interested in the ways in which listening technologies work — and don’t work — as well as the ways in which sound is increasingly deployed (and contested; Slobodan Milosevic didn’t at all like the woman’s voice that was translating him in court at the Hague) as a legal tool. What might save Abu Hamdan from the trappings of trite anti-hegemonic political art (after all, the rise of profiling and other post 9/11 policing measures has inspired a windfall of bad identity-inflected art) is his insistence on and interest in the very medium of sound, regardless of what valence it carries. Abu Hamdan is as interested in the fact that MGM’s roaring lion was the first “non-musical” sound to be copyright-protected as he is in Colin Powell’s peculiar and evidently persuasive use of sound recordings in making his now infamous case for the invasion of Iraq.

In 2011, Abu Hamdan, who spends more and more time in Beirut, held a sound workshop at 98Weeks, a modest two-floor project space in the Mar Mikhael neighborhood of the city, run by the cousins Mirene and Marwa Arsanios. There, through an open call, he worked with participants to create an audio version of Italo Calvino’s “A King Listens.” The short story recounts the tale of a despotic king who compulsively eavesdrops on his subjects from tunnels underneath his kingdom. A victim of his own paranoia, he hears everything and nothing at once. According to a friend who took part in the Beirut workshop, participants worked upstairs in the project space, while Abu Hamdan — the artist–king — worked downstairs, producing the play, which was then broadcast upstairs. “We were trapped,” she said. “Which I hated. Claustrophobia. But I guess it totally worked, conceptually.”