First comes the drone of the sci-fi supercharged tamburas, fluxing and oscillating, too high up in the mix for the bureaucrats and professors at All India Radio, way too high. It’s like the rush of a marsh on a midsummer night with a million crickets, or the howling wind stirring the power lines outside a cabin in backwoods Idaho, or the hushed roar of the stream in front of a hermit’s cave above Dehradun: see the blue-throated god lying there, recumbent and still, his eyes shut, the dangerous corpse of the Overlord waiting for the dancing feet of his bloody, love-mad consort.

This was the sound La Monte Young heard the first time he heard any music from India, Ali Akbar Khan’s 1955 LP Morning and Evening Ragas, in a Music City Records promo-spot on the radio in Los Angeles. Young drove over, bought the record, and brought it back to his grandmother’s house, where he locked himself in his room and listened as the musicians were introduced by violinist Yehudi Menuhin, along with their instruments — this is Mr Ali Akbar Khan on sarod, this is Mr Chatur Lal on tabla, and this is the third instrument, the tambura, played by Mr. Gor. The sound that follows this final introduction lasts only a few seconds on the recording, but it had a dramatic impact on the young composer, who heard in it the basis for a music built around sustained tones and a sublimated, slowed-down rhythmic pulse.

If minimalist music as we know it was in some sense an emanation from that first tambura on the radio, it seems safe to say that it was another tambura that midwifed the birth of its more intimate, disparate heirs. Pandit Pran Nath’s tambura was louder, higher, and harder; it hits you deep in the body with its synesthetic sine wave vibrations and cascading overtones. Hear the world poised at the brink of some radical unfolding, the macrocosm in a bare moment, the maximum minimum, the music of another set of spheres. You haven’t heard the tamburas sing this song before because Pandit Pran Nath was a lifelong student and devotee of these incredible machines’ unearthly sound, adding a special finish of his own fashioning to their resonant lower gourds and tuning them up for hours until they turned into the lightning-black curtains and magenta-midnight light for the Malkauns, a raga with a special place in his repertoire.

It isn’t just the quality of the drone that distinguishes Pandit Pran Nath’s performance of the Malkauns, recorded at midnight in a studio in Soho in 1976. What really stands out in this recording — identified by his former student Henry Flynt as one of the two or three most important ever made — is his voice, stony and austere, with a subterranean intensity. When he hits the tonic note — what in Indian music is called the shadaja — and then slides it slowly, microtonally, downward, you can feel it inside your chest, an impossible emotion somewhere between awe, erotic desire, and annihilation. Some ragas are light-footed maidens dancing through springtime, at play on swings in the flowered groves along the Yamuna riverbank; Pandit Pran Nath’s are cremation grounds, the blue-black color of smoke rising softly from the smoldering log of a sadhu’s fire, the moon on the mountainside.

A musicologist will tell you that a raga is a specific mode, a series of notes that serve as the basis for improvisation, but Pandit Pran Nath and his students would tell you something else, that a raga is a living soul the performer invokes like a celestial, numinous presence moving behind and between the notes, a cosmic teacher that the performer, if he is successful, embodies and transmits, dissolving the boundaries between singer, listener, and song. Each raga comes assigned to a certain time of day, but many artists ignore them in performance, regarding the designations as conventional and dispensable; Pandit Pran Nath only sang midnight songs at midnight. The Malkauns raga is one such, a druggy pentatonic nocturne that some superstitious musicians refuse to play on the grounds that it attracts demons; it works like a powerful narcotic, replacing clock time with another temporality altogether. Do not attempt to operate a motor vehicle under its influence. Put on the recording from 1976 and prepare to lie down on something soft: those four simple syllables Pran Nath sings — go vin da ram — are the name of God.

I first came across the name of Pandit Pran Nath after listening to a recording by La Monte Young and his partner, the artist Marian Zazeela. Often referred to as “the black record” because of Zazeela’s dark kaleidoscopic cover design, it was released in 1969 in a limited edition of two thousand by the Munich-based arts impresario Heiner Friedrich on his Edition X label. The LP quickly became a founding document of the avant-garde underground, a scriptural touchstone for noise music, as well as a cult legend in post-minimalist psychedelia and sound art. Side two comprises “23 VIII 64 2:50:45 – 3:11AM The Volga Delta From Studies In The Bowed Disc,” an extended, highly abstract noise piece generated by Young and Zazeela with a gong given to them by the sculptor Robert Morris. But what caught my ear was “31 VII 69 10:26 – 10:49PM Munich From Map Of 49’s Dream The Two Systems Of Eleven Sets Of Galactic Intervals Ornamental Lightyears Tracery,” which takes up the entirety of side one. The track, recorded in Friedrich’s gallery in Munich in 1969, starts in media res, with two voices — Young’s and Zazeela’s — keening and pushing against each other, sliding up and down against an electronically generated sine-wave drone.

It immediately reminded me of North Indian classical music: Zazeela’s vocal accompaniment quavering slightly alongside the sine wave; Young’s reedy, sliding modal lines. The tone was so mysterious and shifting — especially at the lower end of his range, Young’s voice sounds alien — and yet somehow wrenchingly human with intakes of breath, tiny imperfections, audible effort. I started to feel drugged and overwhelmed, and roughly handled, plied with disturbing visions and physical effects. The music was so serious, so dark and intensely somatic, so utterly forbidding, with no nods or winks, no toeholds; you either laughed off the black record and turned away, or you came away changed.

It didn’t fail to occur to me that what I’d heard might have been the product of some gross act of appropriation, but it just seemed so odd, so disinterested in pleasing me or anyone else. If this was appropriation, its motives were obscure. Then I learned about La Monte Young’s relationship with Pran Nath.

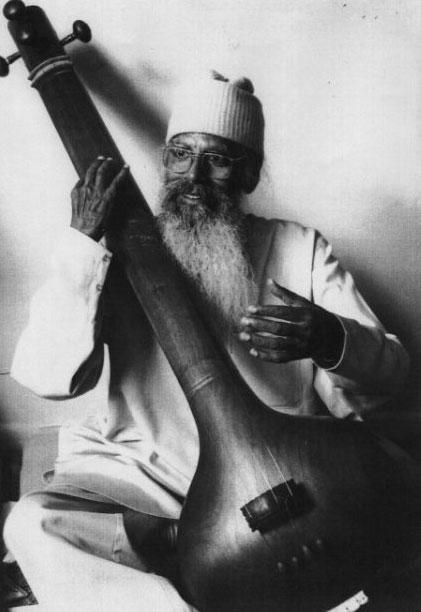

Pandit Pran Nath arrived in New York in 1970 after years of struggling to survive as a vocal instructor in Delhi, and soon established himself as a key figure in the downtown underground music scene. If the influence of Ravi Shankar expressed itself in ersatz sitar-lite solos and bubblegum neo-Orientalist psych-pop beloved by millions, Pran Nath’s took the opposite course, targeting tiny circles of elite connoisseurs — rock snobs of the highest order, drone junkies, and white sadhus. What resulted were life-defining metaphysical commitments and electro-shamanic experiences of aesthetic rapture. He was there, like a force field, at the founding of some of the contemporary art world’s most revered institutions, including the Dia Art Foundation and The Kitchen, with a roster of students and devotees that reads like a who’s who of the American experimental fringe, including the progenitors of drone-rock, post-minimalism, No Wave, world music, and ambient. He reinvented the Indian gurukul, a centuries-old pedagogical institution, for a new era, positioning his practice as an Indian singer squarely within the most avant-garde corner of the American avant-garde. For all this, he’s disappeared from the history of Indian contemporary art, as well as the history of Indian music. Indeed, he barely registers in our contemporary accounts of the development of music and sound art in the 1970s and ’80s. All narratives are based around exclusions, of course, but Pran Nath seems to have found a way to be excluded from every single one.

Untangling fact from legend in Pran Nath’s biography is as difficult as untangling the teacher from the student who tells the story. Born in Lahore in 1918 to a wealthy Hindu family, he is said to have run away from home at age thirteen to live in the house of a singer named Abdul Wahid Khan, first as a servant, then as a student. Khan was a reclusive and Sufi-minded ustaad, or master, in one of North India’s gharanas, extended family-based institutions something like musicians’ guilds that combined pedagogy, stylistic peculiarity, and performance. Abdul Wahid Khan’s was called Kirana, taking its name from a small town near Delhi where a legendary singer-saint named Gopal Nayak had settled some eight centuries ago. According to gharana lore, the Sultan of Delhi had taken Nayak, the finest musician of his age, in tribute after the sacking of the town of Devgiri, along with elephants loaded with precious jewels and gold. Nayak, then, was the first link in a continuous chain of performers that carried his deeply spiritual performance style unchanged into the present day.

In fact, this insistence on the “living link” was as much a product of modern anxieties as it was an objective assessment of musical pasts. Cultural nationalists developed a revisionist historical narrative that sought to minimize the authority of the gharanas, casting them as ignorant and illiterate remnants of a once great and glorious “classical” (read, “ancient Hindu”) tradition. The project of proto-nationalist musicology was framed as one of a grand recovery of a lost essence, and the formidable, secretive, and predominantly Muslim ustaads — often steeped in esoteric and heterodox religious beliefs — were seen, at best, as impediments to that project. Reformists, many of them English-educated colonial elites, were easily scandalized by practices and institutions that failed to conform to their evolving notions of “authentic” Indian culture, and for some of them, the gharanas were embarrassingly visible reminders of India’s incoherent medievalism. Increasingly, Hindustani musicians were expected to shoulder the burden of representing not only their own gharana, but the putative Indian nation as well.

Understanding the politics of classicism and revival in twentieth-century Indian music is essential for mapping Pran Nath’s impact on the American avant-garde. To his students in New York, he was the very embodiment of the timeless and unchanging voice of antiquity; this was a key part of his appeal. But his persona and story — presented by his disciples and improved upon by enthusiastic music critics and promoters — was very much a legacy of India’s early twentieth-century culture wars. In a milieu that placed musicologists and musicians in opposing camps, laying exclusive claim to “the origin” was the ultimate trump card. The most successful of the old-school ustaads carved out a space for themselves by premising their authority on performance rather than transcription — by taking the musicologists’ dismissive label “illiterate” and turning it into a badge of authenticity. Real Indian music, they suggested, was learned by ear, through a process of initiation, repetition, and memorization. Real Indian scales escaped the musicologists’ staff notation, just as real singers always exceeded the rubrics of Western-derived musicological modernity.

In the case of Pandit Pran Nath’s Kirana gharana, this intractable resistance to academia and thorny insistence on the primacy of orality found its natural complement in a style of singing that represented Hindustani vocal music at its most ethereal, solemn, and majestic, focused almost entirely on pitch rather than rhythm, on solitary meditative aesthetic experiences rather than entertainment — on the slow and often unmeasured introductory alap section of a raga, rather than the crowd-pleasing virtuosity of the fast drut. At some point in the early 1940s, Pran Nath pushed this system of musical values to its logical limit. He took up residence at Tapkeshwar, a cave-temple of Shiva near Dehradun, and lived there as an ascetic for five years. According to his students, much of that time was spent singing a single note, the shadaja, accompanied by the sound of the stream that rushed past his hermit’s cell. The story goes that in the late 1940s, his old teacher, near death, tracked him down at Tapkeshwar and beseeched him to abandon the ascetic life, to take a family and teach the Kirana style. A newly independent India was being born, the subcontinent divided. Pran Nath came down from the mountains.

But his passage was a bumpy one: the picture that emerges of his life in the New Delhi of the 1950s and ’60s is one of a recalcitrant and disaffected performer, unhappy with the constraints of university teaching and disgusted by the musical trends taking shape around him. The memoirs of Sheila Dhar, his student at the time, depict Pran Nath before his American reinvention: an immensely talented but eccentric outsider, impoverished and unpractical, utterly out of step with the times. The new nation had institutionalized a certain idea of “classical Indian music,” promulgated by the state-run All India Radio and musicology departments of universities, but Pran Nath either could not or would not make the leap. It must have come as a relief to him when a new type of student started trickling into Delhi in the mid-1960s, seekers without the usual baggage, looking for someone to revere. These Westerners found a stubborn middle-aged man with a limited but oracular command of English, a voice of astonishing power, and an otherworldly mien. Pandit Pran Nath became gurujee, and then a few years later he was gone, leaving behind an Indian cultural scene increasingly hostile to a performer of such suspect religious leanings — he was a devotee of the Chishti Sufi saints, as well as a Nada yogi and mystic — not to mention such stubbornly contrarian tastes.

Many in New York first heard the name of Pandit Pran Nath in 1970, in an April issue of the Village Voice, in an article written by Young. “Nadam brahmam,” it opens in Sanskrit, “Sound is God. I am that sound that is God.” The article introduced Pran Nath as a singer-saint, recounting his background and eventual retreat to the mountains where, at “the age of 28 Pran Nath chose to become a naked singing saint, or naga, and so for five years he sat, clothed only in ashes, singing for God.” This is the most powerful image Young leaves with the reader, that of the naked yogi, the wandering Sufi singer, whose absolute control over pitch and tone constituted a kind of esoteric science, a bridge between the singing of the Vedic gods at the origin of time and the cosmic, vibrational physics and neurochemistry of the future-shocked freaks. It was perfectly in line with the shifting mood downtown. Gone was the cool Zen reserve and rational skepticism of Cage and Stockhausen: Truth had been found, God had been located, and the counterEnlightenment had begun, with Pandit Pran Nath as its spiritual guide and Young as his chief apostle.

It was the first glimpse of an unusual bond between Pran Nath and a man who, by the mid-1960s, was already being hailed as the definitive American composer of the post-Cage era. Young was the father of minimalism, an enfant terrible of the Fluxus movement and one of its earliest escapees; with his Theatre of Eternal Music he had already virtually invented avant-rock, blowing circular modal saxophone lines over the droning accompaniment of John Cale, Tony Conrad, and the frenzied Luciferian pulse of Angus MacLise’s hand drums. In the sixties multimedia underground, where boundaries between film, music, sculpture, and happening were porous at best, the loft he shared with Marian Zazeela was a central node in the network that included artists like Walter De Maria, Robert Morris, and Yoko Ono, and musicians like Terry Riley and Henry Flynt. It was a scene where the high modernism of the fifties was being challenged by a populist performance idiom somewhere between concert and ritual: the Theatre of Eternal Music began playing before the audience arrived and finished after they left, consciousness-altering improvisations that were equal parts hillbilly, dervish, and jazzman. Even John Cage was suddenly square, out of step with a social mood shaped by the Civil Rights Movement and Bo Diddley, the Vietnam War and the assassination of JFK. La Monte Young was at the center of this shift when he met Pandit Pran Nath.

In the grand tradition of American white-man music-swindles, the composer might have just ripped off his style and moved on. Instead something unexpected happened: Young and Zazeela took formal initiation as his students and disciples, beginning a twenty-six-year relationship that would only end — or, as they might say, shift registers — with Pandit Pran Nath’s death in 1996. The really radical impact of this relationship wasn’t in the move away from the piano keyboard scales of the Western tradition toward South Asian microtones and modes, nor in the embrace of improvisation: these were all already happening in an American avant-garde pushing away from European tradition, away from the sterility of staff notation and equal temperament. The really radical break was Young’s emblematic subordination of himself to a teacher, in the fullest possible sense. This was a confrontation with Eurocentric modernity that went far beyond how a piano was tuned or what drugs to take or where to perform; it was a total rejection of a certain way of thinking about personhood, about the role of art, about knowledge itself. Pran Nath became the guru to a generation of American underground art makers who found it in themselves to stick it to the professors and the gallerists and declare themselves important, to experiment outside the bounds, to estrange themselves into other worlds where old distinctions didn’t matter.

Of course, their art changed, too. Jon Hassell practiced ragas on his trumpet for three years sitting by Pran Nath’s side, developing an electronics-enriched cosmopolitan sound without which the “world music” that followed would be inconceivable. Rhys Chatham did sound for Young and Pran Nath while assembling noisy sound installations of his own and curating the first music series held at The Kitchen. Yoshi Wada transformed himself from Fluxus prankster to mega-drone shaman. Henry Flynt crafted a dissident strand of raga-infused hillbilly freak-folk. Don Cherry went mystical. Terry Riley, Young, and Zazeela became like a wandering band of American sadhus, dressed in traditional Indian clothes, performing their own compositions and accompanying Pandit Pran Nath on travels to India and beyond, leaving scratched heads and blown minds on more than one continent.

Pandit Pran Nath’s music changed, too, though in less obvious ways. In a sense any changes in his style had to be less obvious: the role he had created for himself on the American scene was, after all, as the bearer of a timeless revelation. Change, for him, could only be characterized as a kind of platonic unforgetting, a return to divine origins. The invisibility of his innovations are, then, a testament to the success of his art; his new audience and entourage gave him the freedom to take his already unusually slow and severe style of singing and pare it down even further. His insistence on performing ragas at their appropriate times of day became, rather than a simple matter of tradition (as it was and is for many Indian performers), the parameters for ritual happenings. In his concerts, Hindustani vocal music itself, performed beneath op-art light installations in cutting-edge galleries and in Soho lofts, became a kind of post-minimalist liturgy, an aesthetic experience of shared, visionary transcendence that was, at the same time, deeply lodged in the bodies of the listeners and performer. It was ancient and exotic and Other; it was space-age and downtown and Ours.

Describing music with words is inherently difficult, perhaps even more so in the case of a music like Pran Nath’s — so minimal and non-discursive, so profoundly alien to a Western ear — but it is essential to at least try and convey something of its intense charismatic presence. Without that, it would be hard to understand how this uncompromising and eccentric singer, who had traveled so many unlikely roads, became, in 1979, the spiritual touchstone and centerpiece of an art-installation in Soho that was, on the level of its scale and ambition and funding, a close cousin to Donald Judd’s Marfa Project, James Turrell’s Roden Crater, and Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field. La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s Dia-funded Dream House, located from 1979 to 1985 in the old Mercantile Exchange Building at 6 Harrison Street, was set up to be the laboratory for a fringe-science of sound, exhaustively archived and recorded with the best possible equipment, its upstairs rooms pulsing with Young’s incessant electronic sine waves, lit by Zazeela’s magenta op-art neon tubes and calligraphic fantasia. What was once the trading floor became the venue for five-hour performances of Young’s microtonal magnum opus, The Well-Tuned Piano; downtown heads would come to lie or sit in the lotus position on a thick shag carpet, dreaming to Pandit Nath’s cosmic drone.

The Dream House was emblematic of the early days of the Dia Foundation under Heiner Friedrich and Philippa de Menil, who used her fortune to fund the financially impossible mega-projects of solitary geniuses, to realize mad hermetic visions that combined minimal means with maximal scale. Like other early Dia projects, the Dream House positioned itself as the structure for a transcendent, visionary experience; Pran Nath’s voice found its partner in the elemental, aerial physics of Turrell’s volcanic Hopi neo-kiva. The idea was to push the listener inward, inside the earth, inside the body and self, to experience art as a means of flight, as a private experience of aesthetic rapture and embodied, emotional ecstasy. In its explicitly metaphysical intentions, the Dream House was perhaps the paradigmatic early Dia project. “Sound is God,” Young had declared, and this was its temple. When the first phase of the Dia Foundation began to fall apart, and a coup replaced Friedrich and De Menil with a more business-minded board of directors, the Dream House was among the first of the great Dia projects to be shuttered and spun off, its building sold, its inhabitants left to fend for themselves.

The collapse of Dia funding was unsurprising to cynical onlookers, who saw Young and Zazeela’s project as a grand folly, their clothes as an affectation, and their spiritual guide and mentor as little more than a “raga teacher.” Pran Nath relocated to the West Coast, where he continued to teach and practice despite declining health. Young and Zazeela moved back into their old loft at 275 Church Street, opening a scaled-down version of the Dream House that still exists today, along with the Kirana Center for Indian Classical Music. Thirteen years after Pran Nath’s death, they remain committed disciples, making available the precious few publicly released recordings of their teacher at the height of his powers — including Midnight: Raga Malkauns, mentioned above — and hosting annual concerts and listening parties in his memory. At the heart of this story is the remarkable and stubborn fact of their guru-bhakti — their absolute, devotional discipleship. It was — and remains — an astonishing act of surrender, and provided Pran Nath, an eccentric and until then somewhat obscure Indian outsider, with a platform to extend a powerful influence over the American underground art scene at a formative moment.

During an era when, in India, self-consciously “classical” musicians were expected to democratize their idiom and adhere to purificatory standards set by a rigidly hierarchical system of state-sponsorship, Pandit Pran Nath forged an alternative, cosmopolitan model for the future of South Asian traditional music, one focused on advanced sound technologies, spiritualized sensibilities, and a circle of elite connoisseurs, neo-nawabs, and princesses of the underground, holding strange court in a new world. He was a nomadic innovator, an idiosyncratic original, and the godfather of drone; and he’s been written out of the history of Indian contemporary art and music, first by nationalist historians and critics who didn’t know where to place him, and now, by a contemporary commercial scene that scarcely knows his name. But the South Asian art world is changing quickly these days, increasingly focused on new media and electronic arts, on unpredictable collisions between national and global cultural flows, and on manipulations of identity. Perhaps the time is right to sift through the archives again and look harder for the Pran Naths hidden there, lost or hidden lineaments of the avant-garde and the Outside. Pran Nath means “Lord of the life-breath” in Sanskrit — his destiny, and a promise.