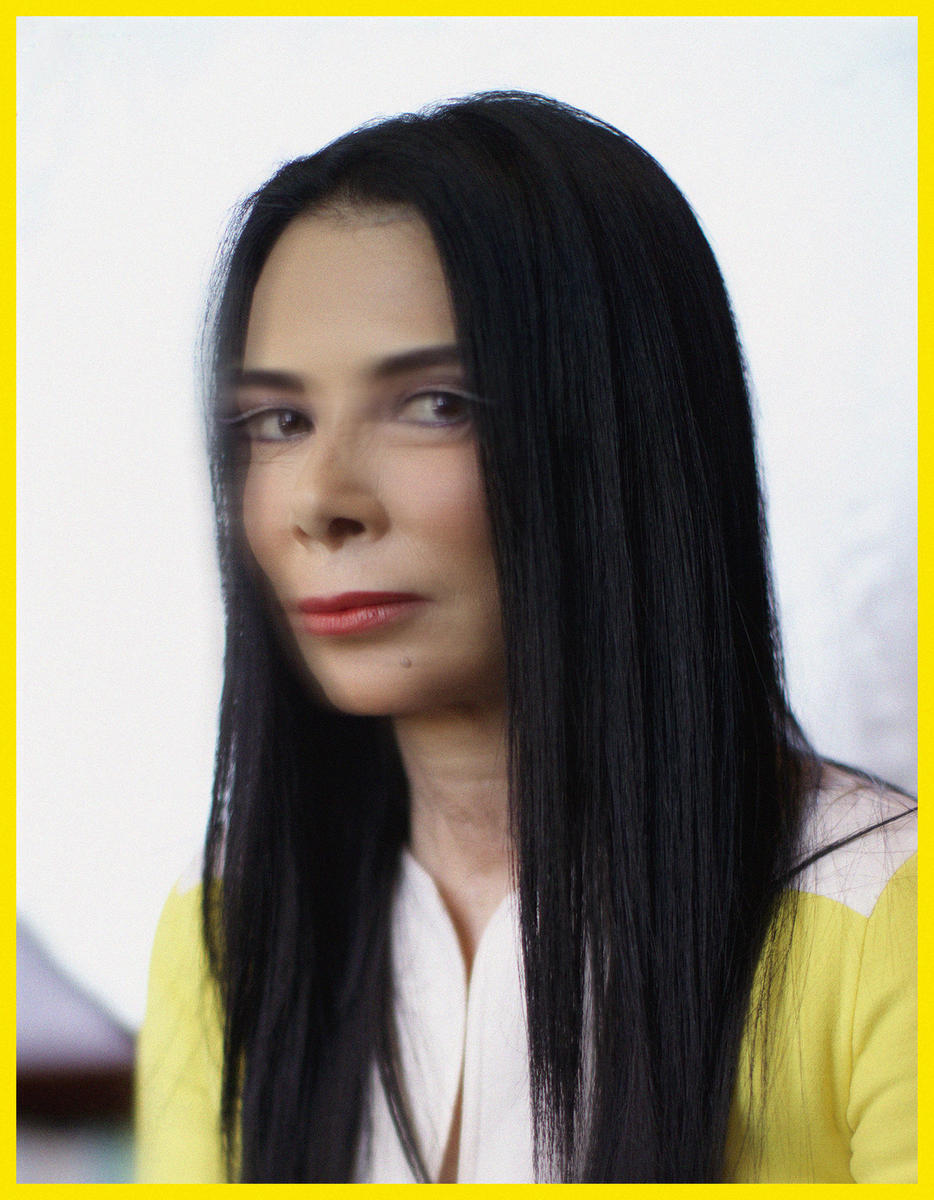

The day of the interview at Mary Boone’s midtown gallery, which looks out on Fifth Avenue and the Plaza Hotel, I was shown to an office behind the larger gallery space, to a seat at a glass table to the right of the gallerist herself, who was on the phone. Mary Boone’s hair is black as Nefertiti’s, though much shinier, and she wears it long. Her features are chiseled, the eyes large and dark like those on a Fayum portrait, the mouth small and well-drawn; there is a certain resemblance to Michael Jackson. Anointed “The New Queen of the Art Scene” by New York magazine in 1982, Boone — born Mary Toney to an Egyptian immigrant family — was a key figure in the careers of such artists as Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Eric Fischl, and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Nearly all of her artists from that era were featured in “Fast Forward: Painting from the 1980s,” an exhibition at the Whitney Museum that Roberta Smith had reviewed in the New York Times a few days before my visit. Smith celebrated the show and the artists who “broke painting wide open” while registering her ambivalence for a decade she has characterized as “a veritable pit of macho swagger, nostalgia, and money.” Boone rejects the charge. “I like heroic art,” she once said. Today Boone shows a mix of artists, old and newer, from Francesco Clemente, Barbara Kruger, and Ross Bleckner to Peter Saul, G.T. Pellizzi, and Ai Weiwei.

While I waited, I was brought a glass bottle of Evian and a slender hexagonal Venini tumbler. Boone was discussing a painting she was thinking of buying but had never seen in real life. The conversation continued for some nine minutes, as Boone and her employees tried out different wordings for an agreement. The whole space was remarkably orderly. Four identical glass desks, each equipped with an Apple display, a wireless keyboard, and a mouse, formed a large rectangle around an empty space. The geometric arrangement of the desks configured the room into a permanent conference of objects as well as humans. The sameness of the things repeated four times, the neatness all around them, lent the space a theatrical presence. I noted that Mary Boone’s feet were clad in black velvet loafers with a gold insignia, possibly depicting a bee.

Occupying two of the desks were Jacob Billiar, registrar, and Naomi Kramer, controller — both young, good looking, and discreetly immersed in their screens. Clearly, the interview was to be conducted in their presence. This is, I was told, the way Mary Boone likes to conduct her work. She has no secrets.

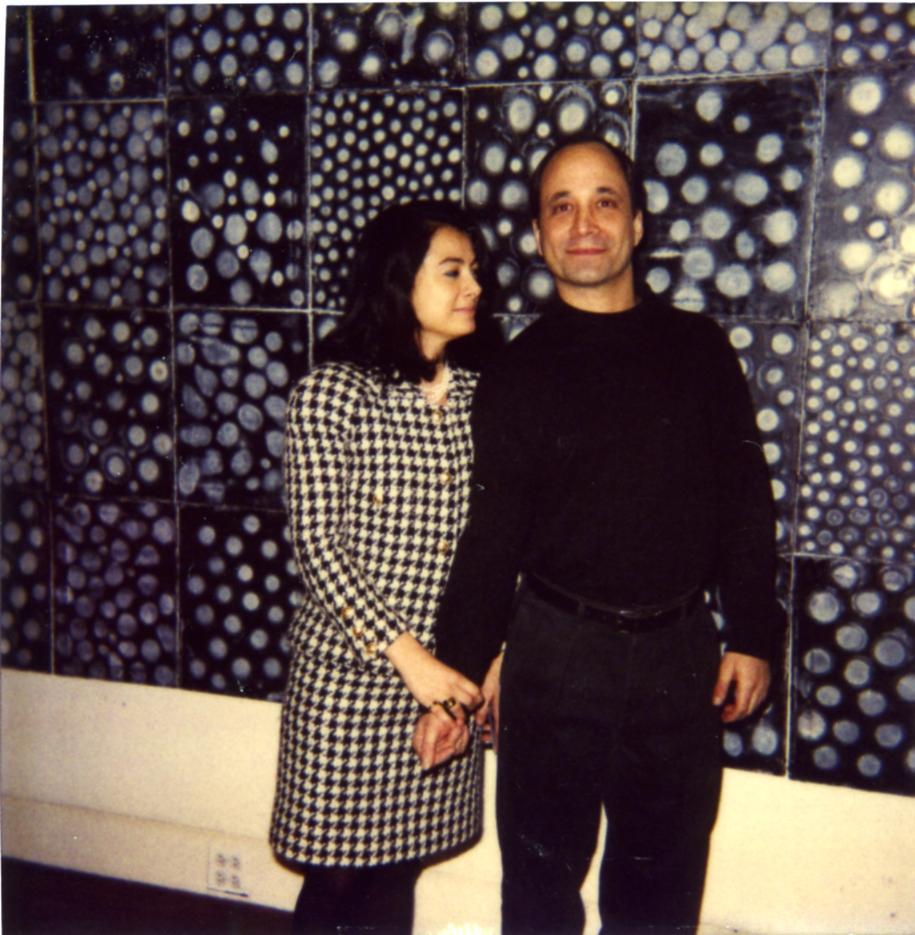

Boone was twenty-six when she opened her first gallery in 1977, on West Broadway in SoHo, at the dawn of an art scene that came to be synonymous with that neighborhood. Her inaugural show featured artists more or less her age, like Schnabel, Salle, and Bleckner, most of them painters. Boone had met many of them while working as a secretary at Klaus Kertess’s Bykert Gallery. In 1979 she married the German art dealer Michael Werner, who represented Polke, Immendorff, and Baselitz and who also championed European painters in the “Neo-Expressionist” style. They had a son, Max. Although they later divorced, Werner was and is an influence on Boone and her program of exhibits. More recently, Boone has worked with the independent curator Piper Marshall, who is credited with bringing more women into the gallery.

Few would deny that she venerates artists, whether men or women. She is known to guard their interests fiercely, making sure, for one thing, that they are paid in good times and in bad. She is famous for issuing invoices the instant a sale is concluded, and for paying the artist equally fast. She is famous, too, for spoiling geniuses. Boone once invited Jeff Koons to lunch at the Jean-Georges at The Mark Hotel on East 77th Street and encouraged him to order anything he liked. He proceeded to order one of everything on the menu. (She went back to the kitchen to give her regards to the chef—and arrange to pay the bill in installments.) On another occasion, she asked the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard to write an essay for a Sherrie Levine catalog. Over lunch she asked him whether $5,000 would be an acceptable fee. Baudrillard, whose English was far from fluent, mumbled a non-response. “Okay then,” she said. “Let’s make it ten.”

When bent on landing an artist or clinching a deal, she can be direct to the point of rudeness. But there is an endearing awkwardness to Mary Boone. At her own openings she is everywhere, hovering, watching over everything but by no means “networking.” I have met Mary Boone many times over the years but at her office last February we had our first real conversation.

Gini Alhadeff: I’d like to begin with your childhood.

Mary Boone: With what, honey?

GA: With your childhood.

MB: Ugh, my childhood. We have to go all the way back there?

GA: Well, everything begins there.

MB: My childhood. I’m sixty-five — that’s a long time ago. I was born in this country, in America, to Egyptian parents. I grew up in a Middle Eastern ghetto in Erie, Pennsylvania. Besides Egyptians, I remember a lot of Syrians and Lebanese. I think a lot of Middle Eastern people went to Pennsylvania.

GA: Why did they go there?

MB: I don’t know. Why do Germans go to Wisconsin or Minnesota? I don’t know. So, my mother is a great cook and I grew up —

GA: Really? What kind of cook?

MB: I think probably the best food in the Middle East is Lebanese, so everyone kind of takes from that. I don’t remember the food we ate as being particularly Egyptian. I remember the bread they call Syrian bread, a flat bread. Pita. My mother even cooked for me when she would come here and Max was little, before she got so old. It makes the house smell so good when you bake bread. That’s what I remember. That’s my youngest memory — this enclave of lots of cousins, lots of family, and lots of food. Then when my father died —

GA: When did he die?

MB: My father died in 1955. He was twenty-nine. I was three and a half.

GA: So young. What did he die of?

MB: Of congenitally high cholesterol… which they didn’t understand in the 1950s. And my mother had me and my two younger sisters. So we moved to Los Angeles, where his family lived, and we were out there for like five years. Hmm… It’s kind of strange to think of it, now, but they actually had an arranged marriage.

GA: Your parents?

MB: Though they really loved each other, too. At least in my little remembrance. I remember them being a very beautiful couple — he was very tall, and my mother, short like me. And… hmm, but my mother remarried like seven years later. She was only twenty-five when he died.

GA: Your father’s death must have been a shock to her. They’d left Egypt together?

MB: No, they met here. They were children when they came over. But the families knew one another from Egypt.

GA: I see.

MB: And my mother — she would hate to hear me say this — didn’t even finish high school. I only say this because I think it played into my psychological being when I became an art dealer. I think growing up in an environment where women were so suppressed definitely had an effect on me. In two ways — I submitted to it on some level and reacted strongly against it, kind of almost at the same time. So that’s always been a contradiction for me.

GA: So your mother was not somebody who could work.

MB: She was very much a mother. She was like an Arab woman — she cooked, she took care of us. She lived for her family and her children. She was very smart. Even though she didn’t have any degrees and wasn’t well educated, she was very smart. Instinctually smart. And she pushed me a lot, particularly after my father died. My sisters, too. She pushed all of us to get a very good education, because she saw that as being a kind of guarantee. And then of course — because you and I are the same age, you’ll remember this — the Women’s Movement came about just as we were coming onto the job market. I think that gave us a lot of opportunity but also a lot of doubt. I remember hearing Gloria Steinem at Hunter College. She said, “I know that all of you are thinking that there is a lot of freedom for women now — but will you really be able to succeed?” There was a lot of fear, a lot of doubt. “Okay, if I get the opportunity, am I going to be able to utilize it?” That’s the kind of environment that I came into the world with. And, you know, I started out working as a secretary.

GA: At the Bykert Gallery. But before that I am interested — and excuse me for interrupting you — what kind of house did you grow up in?

MB: A small house. I grew up poor. The houses I remember… one was in Pennsylvania, on Cherry Street, and that was a tiny little clapboard house. And then the house in California, a little pink stucco house.

GA: That was your father’s family’s?

MB: Uh-huh. We mostly lived with family, extended family. I never got the impression that that was uncommon. But I think it’s more uncommon among wealthy people. You know, they don’t live with —

GA: Well, these days… [Laughter]

MB: Now it’s coming back. [Laughs] Kids get out of college and they go live with their parents.

GA: So, one story I heard about you is that you lived on a reservation for a time. Was that in California?

MB: Uh-huh. There was a period when my mother was dating a man named Rodd Redwing, who’d played the Indian in all the Walt Disney westerns. Disney actually built a reservation for Indians, and we lived on it.

GA: Really? Was it a particular kind of Indian reservation?

MB: I think it was Hopi? No… it was really mainstream Indians, actually. I didn’t know Walt Disney, but I think he was a pretty imaginative human being. He wanted the Indians who starred in his movies to be happy, so he made them their own little home. You have to realize that Los Angeles wasn’t built up the way it is now. Where Burbank is, and the studios, they had a lot of land. It was the old Hollywood.

GA: Was that strange for you, living on the reservation?

MB: I don’t remember it, except for in pictures.

GA: And you could easily pass for American Indian.

MB: One thing that moving to California did prompt was feeling like an outsider. Because it seemed that everyone there was blond with blue eyes. They were tanned, but from the sun. And here I was with black hair, my olive skin —

GA: You felt that way even on the reservation?

MB: No, and I think that’s why I kind of liked it there. Kids are very cruel, you know. The funny thing is that my son went to nursery school at the Presbyterian church here — this beautiful boy who is very pale-skinned and has beautiful brown hair and is fair, like his German father, and he comes home after the first day of nursery school and he says, “Mom, why isn’t my hair the same color as yours and why don’t I have dark skin and why don’t my eyes go like this?” [Gestures] So everyone wants to be what they think is the norm. In California, most of the time, I was surrounded by beach babes — you know, blondes — and that’s what I wanted to be. But then my son was in a culturally mixed environment, like New York is —

GA: So he felt too white.

MB: I just thought it was funny. Did you ever feel like that, or no?

GA: Oh God, yes.

MB: The kids would ask me if I was an Eskimo. [Laughter] I wasn’t even old enough to know that that was insulting. But I knew when I told my mother, because she said, “Who asked you that? Who was it that asked you that?”

GA: [Laughter] Kids can be horrible. When I was in school in Japan, they made fun of me for being tall, unusually tall.

MB: Well, that’s very funny. The opposite happened to me in Japan. When I first opened my gallery Leo Castelli introduced me to this big company, the Seibu company. A lot of his artists did very well in Japan — Jasper Johns is a big hero there. So Leo chose me to follow him. The Seibu family welcomed me and they came to pick me up at the airport. And they were shocked, because they thought from my name that I would be a tall blonde, and here I was this little person who looked like their people. And it was great, actually. I did all kinds of talk shows and interviews; a lot of young women wrote to me for years after that. It was a great thing. The other thing that made me think of that was that they had gotten me a special room at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo that had Western beds — big long beds. [Laughs] I had a bed ten feet long! [Both laugh]

GA: Can you remember a particular moment when you became interested in aesthetics?

MB: I always was.

GA: Was there something that influenced you?

MB: No. I knew you were going to ask that question, so I was thinking about it last night. People always want to know when you knew, the moment you felt that art was your calling. But for me, it was just something I grew into. It’s funny how your path is kind of decided. We moved to Michigan when I was ten, after my mother re-married, and we lived in Detroit, Bloomfield Hills, Lansing. We would go to Traverse City in the summers.

GA: Why did you move around so much?

MB: My stepfather, Mister Boone, was an inventor. He invented a coupling system for trains that’s still in use, for instance — things to do with cars, which is why we were in Detroit. He also worked for Kodak and modified the camera for the space shuttle. He was an engineer and designer. He was a pretty amazing guy — my mother was lucky! So in Traverse City one summer I met a woman who went to the Rhode Island School of Design. And then we spent the next summer on Block Island, so it was easy to go to Providence and visit RISD. I just decided that this was a place I wanted to go to. After that I came to New York to work at a museum, which lasted exactly one week. I was a secretary for Marcia Tucker at the Whitney and Marcia Tucker told me, “You would be really great working in a gallery, because you seem to like artists.” In those days museum people didn’t work with artists as much as they do now. I told this to Lynda Benglis and she said, “Oh, no problem — my boyfriend has an art gallery.” And her boyfriend was Klaus Kertess, which is how I landed in the best gallery in New York.

GA: How did you know Lynda Benglis?

MB: She was my teacher, as was Robert Morris. Both of them were great teachers, and very, very generous.

GA: This was at RISD?

MB: No, they were teaching at Hunter. My first year and half in New York, at Bykert, was part of my work-study and I got credit for it. But I met Lynda when she was giving a lecture at the Rochester Institute of Technology. I had gone to visit my parents at Thanksgiving and —

GA: This must have been when your stepfather was working for Kodak?

MB: Yes. And that’s when Lynda was doing those big sculptures out of urethane that were phosphorescent.

GA: The ad in Artforum of her holding a long, latex dildo was around the same time?

MB: It was all during that time, yes. I think that ad was… Bykert was open when that ad went in. I think it might have been 1973 or ’74? You know there were several ads — there was hers, and Robert Morris’s response to it, then she did another. It was all carried out in a very public way. Funny. I really admired her. I was looking for role models. It was hard to find women that you could use as mentors in the 1970s, even though the Women’s Movement was in full swing.

GA: Because they didn’t occupy those roles?

MB: Yeah. Ileana Sonnabend was another. Leo Castelli and Michael Werner were role models to me, too.

GA: What was it like working for Klaus Kertess?

MB: Oh, he was a wonderful person to work for. He was a scholar and he loved art and he loved artists. At Bykert I met people like Brice Marden and Chuck Close. Michael Snow and Paul Sharits. It was a pretty diverse group, not just painters. The 1970s was a great time to learn because there wasn’t that constant concern about money. I mean, the city was bankrupt, so the focus was more on the art. Artists took a lot longer to develop than they do now, and I think they became truer to themselves as a result. Even now… someone like Barbara Kruger was such a great artist because people didn’t understand her right away. I mean here she is, she is about seventy-two, and pieces she did even thirty years ago are relevant today. It’s hard to be like that as an artist.

GA: Do you remember the first artist you ever dealt with?

MB: Julian Schnabel.

GA: Really? You must have had others before him?

MB: Well, the first show that opened after I started working at Bykert was Chuck Close. A wonderful person. He always says, “You met me first, and it was downhill from there.” [Laughter] He was sweet. In fact, all the Bykert artists were very sweet to me. We exchanged stories — that was a lot of how you learned. Actually, the first artist I really met was Ross Bleckner. That was at Bykert. And Ross introduced me to Julian, because Julian was painting his ceiling at the time. Not like the Sistine Chapel — he was just painting Ross’s studio.

GA: [Laughter] So it was Ross Bleckner you met first?

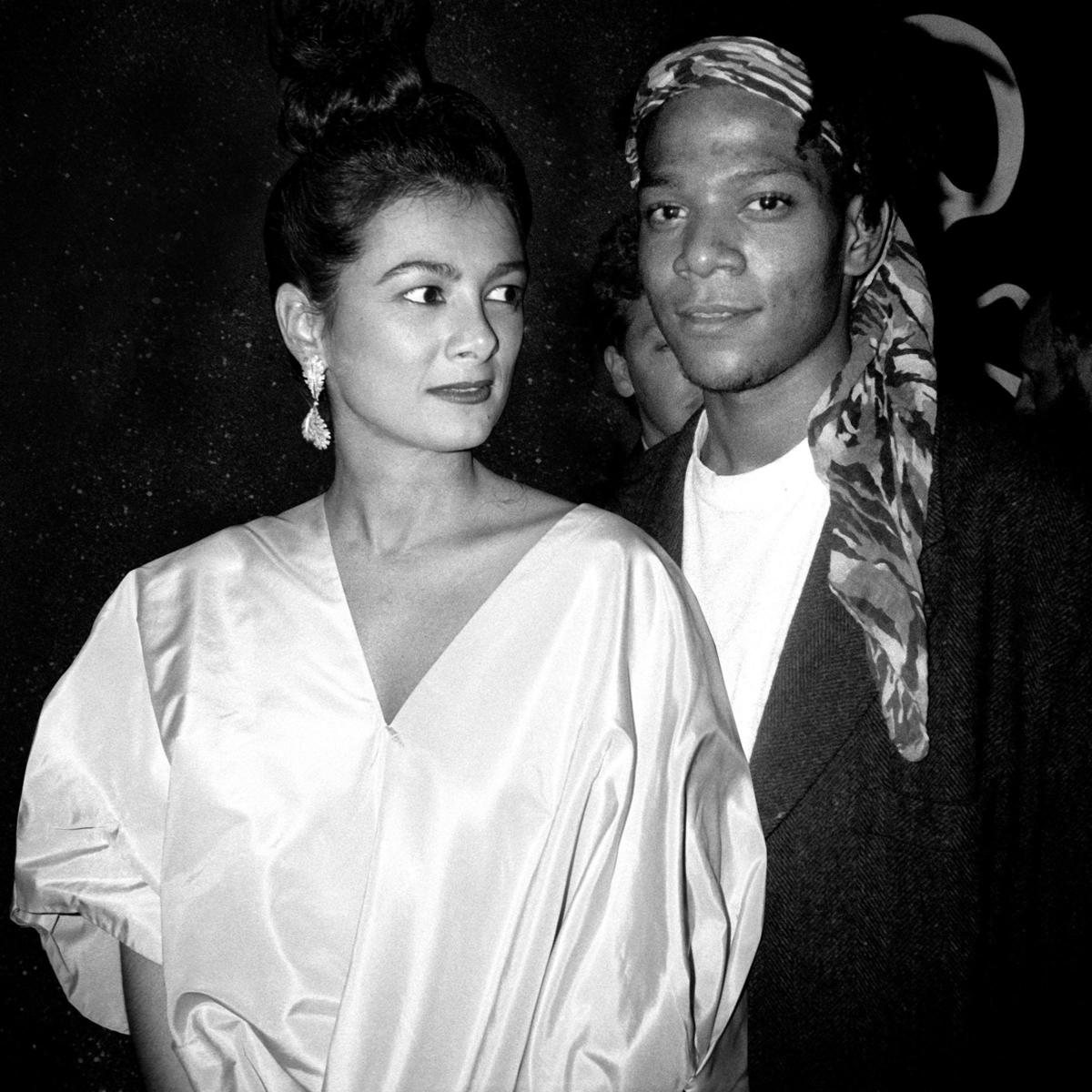

MB: Yes, and he introduced me to Julian and Barbara Kruger and then the whole CalArts group, which was David Salle and Eric Fischl, Sherrie Levine. And then separately, I met Jean-Michel [Basquiat] and the Italians, particularly Francesco Clemente.

GA: So the very first show you did in your own gallery was with Ross Bleckner?

MB: No, it was a group show with all those people — Ross, Barbara, Julian, Andy. David Salle. We all hung out together. It was a generation of people who basically knew each other.

GA: Was it one painting for each artist?

MB: Uh-huh. I covered every surface of my tiny one-thousand-square-foot space.

GA: That’s interesting. I didn’t realize Andy was involved so early.

MB: I think he started coming around because he felt more idolized by these young artists that I was showing. He didn’t feel part of the generation he belonged to — that whole Black Mountain group, like Jasper Johns and Bob Rauschenberg. Cy Twombly.

GA: The Black Mountain people weren’t as interested in Warhol?

MB: No, they cut him out. Even Leo never really understood the work.

GA: Castelli? Really?

MB: I loved Leo. He was a great person. An important person. He was a gentleman. He was literary and he was cultured. He loved art and he wasn’t motivated by money and it kind of informed a lot of people. He set the tone for the art world, and I think it was a very different art world because of him. He was a real role model for me, as I said. But he definitely never understood Andy. That’s why Leo didn’t lend Andy’s work as much as that of his other artists.

GA: Wouldn’t lend it?

MB: Didn’t consign it. In one of my group shows, fairly early on, I had a Warhol Mao painting. I got to choose from about twenty of Andy’s paintings, and it was only about twenty-five thousand dollars. And it didn’t sell. I mean, Leo obviously hadn’t sold any — he had like twenty in his racks. Anyway, Julian and Jean-Michel and Francesco certainly idolized Andy. And there was more of a connection between what Andy was doing and some of the German artists I was showing, particularly Polke.

GA: That was after you met Michael Werner?

MB: Yes, after I met Michael — but that was in 1979.

GA: Ah, such a short time, I didn’t realize. One thing I was curious about is that early show of Julian’s work you did with Leo Castelli. How did that happen?

MB: Well, I’d had the idea of getting Leo involved because I thought it would help me. It was easy to see that Julian was very ambitious and wasn’t long for my tiny little gallery, so I wanted to buy more time by getting him a museum show. And showing with Castelli was like showing at MoMA, in my mind. But when I first went to him Leo said, “Oh, no way. I haven’t taken on a new artist since Richard Serra and that’s been ten years. I couldn’t possibly do that.” Then Barbara Jakobson went and talked to him. She is so smart and she was really a great friend to me through all of that — I still consider her a friend. And she told him that it would be a good idea.

GA: Really? [Laughter] I’ve known Barbara for forever. She was a publisher of a magazine I edited out of her guest-room in the late 1980s. And a longtime MoMA trustee, as you know.

MB: It was her. She talked him into it. And it did bring a lot of excitement to Leo’s gallery. Though also some controversy. Because not everyone believed that these were good artists. Don Judd, for example.

GA: He didn’t like Schnabel.

MB: Definitely not. Roberta Smith quoted him in her review of the Whitney show — she made sure that that Judd quote was very visible. She’d worked for Don and they were good friends. “David Salle might learn how to make art and maybe Julian Schnabel will grow up,” or something. [Laughter]

GA: She quotes him as saying that “talent may strike” Mr. Salle…

MB: It was insulting. Hilton Kramer wasn’t very enthusiastic, either. There was a lot of controversy with these artists at the time. Listen, when I showed Picabia, they said terrible things about him. He was scandalous. And he’d been dead for thirty years already.

GA: When did you show Picabia?

MB: In 1983. It was thirty-five paintings from 1929 to the end of his life in 1953. They were beautiful, beautiful paintings…

GA: Where did they come from?

MB: Michael had been collecting them for years. That was Michael’s vision. I loved those paintings; they connected very much to David Salle and Sigmar Polke. Picabia was just a great artist. And now MoMA did kind of the show we did, but thirty years later.

GA: So when that show went up it was criticized?

MB: The review in the Times was so upsetting. I was on the phone to Francesco in tears and Francesco, being who he is, said, “Oh, but Mary, can you imagine? If an artist can be scandalous at his age, when he is dead — you know, that’s such a great thing.”

GA: [Laughter] That’s wonderful.

MB: The funny thing is, we only sold seven of them. But of those seven, five of them went to artists, including Francesco and including Andy.

GA: I was thinking back to your first gallery and wondered what was the first space you ever determined — the first place you lived in, that was your space? Was it at college?

MB: Yes, probably at RISD. You know it’s funny that you say that, because I’ve always been… I never studied architecture or anything like that, but I’ve always particularly identified with spaces. Even when I had my tiny little one-thousand-square-foot gallery, I tried to make it as beautiful as I could. People said that I brought an uptown aesthetic downtown, but what they really meant was that when the galleries downtown started out, they weren’t at all like mega-galleries are today. They were very funky. They slowly got more and more finished.

GA: Speaking of funky, do you remember that store called Paracelso next to your gallery?

MB: It was still there on West Broadway until a year ago. Someone was talking to me about her at an opening that I was at on Saturday.

GA: She’s still around? Did you know that her name was Luxor Tavella?

MB: I did not. I always thought that Alba Clemente and Helen Marden kept that woman in business.

GA: You think that’s true? It was the strangest store.

MB: It was all kind of Indian and Middle Eastern… clothing, pretty much, wasn’t it?

GA: Yes, all sorts of exotic feathers and chiffon layers. And she had many tattoos and a lot of henna —

MB: She had a lot of henna.

GA: Speaking of henna — and as you know, Bidoun is very interested in your Egyptian background, so I would be remiss not to ask — have you ever been to Egypt?

MB: No. Bad me.

GA: Do you ever see any Egyptian relatives, then?

MB: Oh, yeah. I mean, they all live here.

GA: But your parents didn’t teach you Arabic?

MB: No, they never taught us. Do you speak Arabic? You were born in Egypt, weren’t you?

GA: I don’t.

MB: I know, I should.

GA: I spoke it as a child.

MB: Really?

GA: Yes, in Alexandria. I spoke French and Arabic, first, and then I had to learn Italian, so I think the Arabic went out of my head.

MB: Well, they say that that’s the best time to learn a language, when you’re really little, because then you speak it with no accent.

GA: I would interpret for my mother when I was three or four.

MB: That’s what I always envied about Leo — that he spoke five or six languages just fluently. And easily moved back and forth. I think it makes people feel comfortable. Now it would be a particularly happy thing to speak Arabic — Arabic or Chinese.

GA: Do you know whether your parents came from Cairo or Alexandria?

MB: Cairo, both of them.

GA: Presumably it was their families who decided to come here?

MB: Oh, I’m sure. My mother was born in 1929, and my guess is that they came over here when they were still young, so probably right after the war started. A lot of people changed locations, then.

GA: Do you know what their religion was?

MB: My guess is they were probably Copt because they came here and they went into the Greek Orthodox Church. My mother broke away from that as a teenager, wanting to be independent, and became a Presbyterian.

GA: That is so interesting. And you are Presbyterian also, no?

MB: Uh-huh.

GA: All I know is that they give out nice little sandwiches at Easter.

MB: They do?

GA: On soft white bread. I got them once when a friend took me to that church on Madison and 74th Street.

MB: But that’s my church! I like that church because they have a big outreach program. They work a lot in the community.

GA: They used to have a pool, no?

MB: They have a bowling alley. I love bowling.

GA: I love bowling! So they have a big outreach program —

MB: They have a homeless shelter there, and a program for the children that go to nursery school there, and a grade school. They have a program for children to visit patients who have Alzheimer’s and read to them. Max did that and he was really great.

GA: Do they have yoga classes? I heard that you do a lot of yoga.

MB: Oh, I love yoga. But I’m not very good at it. I love to do my yoga, particularly at the ashram, but you know I’m too… You have to be really flexible and disciplined.

GA: Where is the ashram?

MB: In Calabasas, California.

GA: In Calabasas?

MB: It’s near Santa Monica. It’s beautiful.

GA: And is it an American ashram, or an Indian one?

MB: Oh no, it’s American. It started in the 1960s. It’s kind of like Esalen. They’re vegan and they raise all their own food.

GA: How did you find it?

MB: Oh, a lot of people I know go there. They have a very rigorous hiking program and they have very good yoga. The guy who invented Bikram Yoga started out there.

GA: Was it called Bikram?

MB: No, no, no — the ashram is just called The Ashram. It’s very pared down. It’s not fancy at all. There are much fancier places, like the Golden Door. This is really about exercise and eating right and, you know, spirituality.

GA: What sort of spirituality?

MB: Meditation and yoga.

GA: It’s not Hindu or Buddhist?

MB: No, it’s not religious. It’s spiritual. You know Max goes, too — that’s how he started doing yoga. He asked to go.

GA: He asked to go?

MB: Yes. It was so funny. He said that every time I came back I always seemed so happy.

GA: That is sweet. [Laughter] I have to admit that I find it amazing that you’ve never been to Egypt. You never felt like it?

MB: No, I felt like it, but… the thing is that most of my travel has been to do with the gallery. And I’ve never… I mean, now would be the time to go to Egypt, with the art fairs and artists. I used to travel all the time. All during my twenties and thirties, I was on a plane every other week. I think I kind of used up that interest in travel. I know this wonderful collector, Nazim Ahmad. He lives in Beirut, Lebanon. An incredible collector and just a wonderful person. He buys from his heart. I feel like he knows me so well and I feel like I know him so well. And we’ve never met! He doesn’t like to travel, either.

GA: Did your parents go back to Egypt, though? To visit?

MB: No, they never went back.

GA: So they really left forever.

MB: They weren’t the kind of wealthy immigrants who traveled over here and then had the freedom to go back. But also, I think, to a certain extent… they just wanted to be in America. I mean, I remember when my grandfather, who never even really learned much English —

GA: Your father’s father?

MB: No, my mother’s father. He never really learned English. And he never went back. He lived in a Middle Eastern ghetto, and he talked to all of his brothers and sisters and cousins. But, with his grandchildren… I never had a real conversation with him, I never could understand what he was saying.

GA: Because he spoke Arabic.

MB: His English was butchered. All I was saying is that they were so happy to be in America.

This was in the 1950s, my memories of it, but they came over I think in the 1940s.

GA: I wonder what prompted it. Do you have any sense what made them come here?

MB: I don’t know. Didn’t all immigrants come over here because they thought they would have a better life? I mean, what was it like during the Depression in a third world country? They came over here and they worked on the assembly line for General Electric, or —

GA: That’s what they did?

MB: That is what I imagine. I know that my grandfather worked for General Electric. My mom’s dad. Whose name, funnily enough, was Michael. I was named after my mother, actually.

GA: And your father’s name?

MB: George. Geōrgios. But isn’t that like all the Koreans and Chinese — they come over here and they get American names?

GA: So in a way they remained in an Egyptian community, but separate from both Egypt and America.

MB: Yes. But I get the feeling that all of those first-generation people grew up in ghettoes. You really see that in New York with German Town and Little Italy.

GA: Okay. You know, I remember, one Saturday in the late 1980s, not far from Little Italy — at your gallery on West Broadway — hearing two women coming out of an Eric Fischl show and one of them saying to the other, “Oh yeah, that Mary Boone, she’s a real tastemaker.”

MB: Well, that’s sweet. Listen, I feel my legacy is about all the artists that I’ve helped — that, to me, is the most important thing. And I guess being a tastemaker is part of that.

GA: Have you always seen your role in those terms? As helping artists?

MB: Pretty much. I find the whole notion of celebrity embarrassing. I never know what to say when people come up to me and say, “This is such a great show.” Yeah, I provided the walls and the lighting, but… the artist made all the work, the artist took all the risks. It is the artist’s neck that’s on the line when the reviews come out and everything. I think the dealer is in a pretty modest position, and the more in the background they stay, the better it is for the artist. Usually. And also the idea of being, you know, unselfish, or selfless — I think that is important, too. Which is hard to explain to people now. Sometimes I’ll hire people who think that working in a gallery is about going to openings and drinking champagne and wearing fancy clothes and being on television. I mean, these guys [nods at her gallery staff, sitting at their desks] are definitely millennials, but they are wonderful, hardworking, dedicated.

[The gallery staff does not look up]

GA: Fischl said something wonderful about you. He said that you —

MB: Must have been a long time ago… [Laughter]

GA: I don’t know when it’s from, but it gets quoted a lot. He said that you’d “changed radically. Dramatically but slowly, if that’s possible.” That you’ve become “somebody who — through her spiritual development, her revelations — serves her community.”

MB: I what?

GA: That you serve your community.

MB: Yes. You know what? I like to help people. I do like to help people. I don’t think I’ve changed, though, I think Eric is wrong about that.

GA: So no revelation?

MB: I don’t think I’ve changed, I like to help people. I always saw a gallery as a kind of educational tool. I believe that art can change the way people look at things, how they think. I even feel optimistic about this horrible time we’re going through.

GA: Really? How so?

MB: If you look back on the 1960s, which was another really dismal time, politically, a lot of great art got made in more or less direct reaction to that. And everything is politicized now. When we were in the Obama era and things were peaceful and nice and people were proud of the person that was representing them, people didn’t really think about politics. They just let everything go. Now everything is a political issue. And everything Donald Trump does is questioned; it’s questioned by the courts, it’s even questioned by the people who voted for him, I think. And nobody takes anything for granted. Living like that is a very creative way to live. That’s the way artists live all the time — they’re always looking for the way something can be done better. So I feel hopeful that a lot of good art and artists will come out of this time.

GA: When did you start showing much younger artists? Was it in the 1990s, or later?

MB: I always showed artists pretty much at the beginning of their careers. I like being there in the beginning, when you can really help make a difference. Although people like Brice Marden and Richard Artschwager… Well, Brice I knew from when he was maybe twenty-eight, twenty-nine, but when he was in my gallery he was in his late forties, early fifties. But his career was still a young career. He felt that he wasn’t getting the kind of attention from museums and collectors that he wanted, and we were able to change that. The same thing for Richard Artschwager, who was at Castelli for twenty years and never had a review in the Times. So sometimes we’ve taken on older artists that still had young beginnings. But mostly we’re with people at the start of their career, like Jeff Koons or Jean-Michel.

GA: You had shows with Jeff?

MB: Just one. And with Jean-Michel, the same thing — I mean, he was nineteen when I started to show him. But what I was going to say is that we still show artists who are in their twenties and thirties, but now that I’m so much older, they all seem so much younger. [Laughs] It used to be that artists and myself, it was like we were sisters and brothers. Now I’m as old as most of their parents. We showed Sadie Benning and I met her father who is pretty much my age. And Leidy Churchman. Silke Otto-Knapp is in her mid-forties, too, or early fifties. Oh — tell Bidoun! Tala Madani is an artist we’re going to be showing next season. She’s from Iran. She’s… how old is Tala?

[A voice calls out from the office]

She’s thirty-six. She just had a baby. So she is young! [Laughs]

GA: Your program has changed a lot over the years.

MB: I hope so. I’m really thinking a lot about women artists. But I have to say, I don’t think of myself as being a proponent of “macho male” painters. Roberta Smith wrote that, in connection with the Whitney painting show. She originally wrote that in 1991 in a review of a Barbara Kruger show I did. And actually neither David nor Julian were with my gallery in 1991. But also, I look at Julian’s paintings — what makes those paintings macho?

GA: There’s something quite feminine about them, actually.

MB: Yes. They’re made with dishes.