It’s hard to know who was the first to say: “Art is anything you can get away with,” but chances are good it was Marshall McLuhan, not Andy Warhol. We live in curious times when both eloquent and abrasive arguments can be made to say whether mopping a palazzo floor with the diluted blood of a drug war (Teresa Margolles), cooking dinner for a crowd of strangers (Amal Kenawy), or flipping a light switch on and off 2,000 times to communicate with neighbors (CAMP) qualify as art or not. As the field of contemporary art grows ever more diffuse, the works that are the most fun and effective tend to be those that push hardest at the boundaries of what constitutes art at all. Once radical gestures, meanwhile, get a little dull when they gather consensus and are given a name. Research-based practice, for example, has become so establishment it even sounds boring.

For the artist Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, however, research is far from solemn or dry. It is more like a torrent of associations and obsessions, a method of working that tumbles after captivating leads, loose threads, dead ends, and tunneling digressions. Abonnenc was born in French Guiana and raised in the capital Cayenne. He moved to France when he was fifteen, went to high school, and lived in Marseille for a while. These days, he is nominally based in Paris, though he spent the first few weeks of this year setting up a new studio in London, as an artist-in-residence at Gasworks.

Abonnenc’s research sketches out a complex map running from France and Portugal to West Africa and the West Indies. As those trajectories pass through revolutionary movements, civil wars, and other intractable conflicts, they splinter off toward partisans in Cuba and Algeria, patrons in China and the former Soviet Union, and financial backers in the Gulf. Most of the works he has produced over the last eight years delve into the histories of colonization and decolonization. Each of them picks at the tangled relationship between a struggle for independence and the formation of identity, tests out the delicate balance between a desire for liberation and the longing for some sort of home (which invariably becomes a kind of trap), and digs into tender notions of desire and time.

Underlying these investigations is an inquisitive, childlike wonder, as Abonnenc falls headlong into fascinations with radical figures, revolutionary movements, and those moments in time, in a messed-up place, where something totally unbelievable suddenly seems possible. But he also pushes past the wild details and colorful characters to ask critical questions: Why do some of the most tortured episodes in history provoke some of the most mind-blowing works of art, film, literature, music, and graphic design? Do those works fictionalize history as it happens? When those works are revived, decades later, are they mistaken for real events? Which is more revealing, the glint of nostalgia that revolutionary relics produce or the experience of the search, measuring a distance that can never really be bridged?

At Gasworks, Abonnenc has filled his studio with stacks of Tricontinental, the Havana-based magazine of third-world liberation movements, known for its avant-garde art direction (see “Revolution By Design” in Bidoun #22); copies of the Algerian journal Révolution Africaine from 1963; issues of Angola Bulletin, published by the Netherlands Institute for Southern Africa; the first set of postcards printed in newly independent Guinea-Bissau; and piles of black-and-white photographs taken on the location of an ill-fated film. All of this material feeds into a work titled Foreword to Guns for Banta, which is Abonnenc’s most ambitious project to date. As of late January, he was lost in the transcripts of Portuguese soldiers who fought colonial wars in Africa. “I spend days and days reading these testimonies,” he said.

Over the course of a Skype conversation and a fitful exchange of emails, Abonnenc touched on Frantz Fanon, the poet Édouard Glissant, the literary movement Négritude (vexed, capacious, and much criticized), the left-wing publisher François Maspero, the filmmakers Chris Marker and Flora Gomes, and the brief history of a collectively produced genre of militant cinema. Talk to Abonnenc long enough and you start to see connections everywhere, like mesh over your eyes. It all sounds incredible — research as a real and active pleasure — and yet you wonder how he finds the time or focus to get anything done.

Between 2004 and 2007, Abonnenc retraced the expeditions of a doomed nineteenth-century explorer to produce a suite of dazzling, deceptively decorative wall-size drawings, Paysages de Traite (Slave-Trade Landscapes), and a series of haunting photographs called Terra Nullius, meaning land belonging to no one according to Roman law. His starting point was a bound collection of Le Tour du Monde, a weekly travel journal launched in 1860 by Hachette in France. Famous explorers such as Richard Burton and Henry Morton Stanley were dispatched to the far corners of the globe and returned with tales of adventure in exotic, untouched lands.

A team of in-house engravers illustrated their stories for a public newly attuned to the aspirations of travel. The journal was wildly popular. None of the engravers had ever left France. Their illustrations were born of the imagination, and they were basically all the same, like Victorian wallpaper in varying patterns for Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Abonnenc found the issue on French Guiana, informed by the adventures of Jules Crevaux, a doctor who explored large swathes of the country’s interior. Crevaux made four expeditions to French Guiana. On his third, he studied botanical specimens, which were illustrated in Le Tour du Monde. On his fourth, he was clubbed to death by a group of fishermen suspicious of his intentions. For the exhibition Watchmen, Liars, Dreamers, installed in the Paris art space Le Plateau last fall, Abonnenc delved deep into the work of Julius Eastman, a largely forgotten American composer. Eastman gave minimalism a pop twist and wrote three notable pieces for multiple pianos in the late 1970s — Evil Nigger, Crazy Nigger, and Gay Guerrilla — before dropping out of the avant-garde music scene with a crack problem. He died in 1990 at the age of 49. In an obituary for the Village Voice, the critic Kyle Gann noted, with regret, that Eastman was brilliant, and that most of his scores were lost.

Abonnenc contacted the composer Mary Jane Leach, who spent seven years tracking down and compiling those scores, and invited her to give a lecture. The two then orchestrated a performance of the aforementioned pieces, along with If You’re So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich? Eastman’s music had never been performed in France. Abonnenc left two baby grand pianos in the venue for the duration of the show, and looped the recording of the concert.

For another, more low-key performance piece, Abonnenc periodically recasts a reproduction of a ring he inherited from his great-grandfather and lost. The silver piece is embellished with an ornate skull and engraved with the line “I will maintain through reason or strength,” the motto of Counani, the Republic of Independent Guiana, which established itself for five short years, from 1886 to 1891, before it was re-appropriated by France and Brazil. Abonnenc has been researching this ring for ages, but he’s gotten nowhere. He has no idea what it means, how his great-grandfather was involved in Counani, or whether the family lore that says he was a freemason is credible or not. True to his interest in copies and fakes, Abonnenc reproduces the ring over and over again, and gives it to other people to wear. Every time he recasts it, the legibility of the engraving fades.

Two years ago, Abonnenc decided to look for the six reels of an unfinished film that went missing in 1971. At the time, he had no idea whether the reels still existed. To this day, he still doesn’t know. The story he has pieced together so far is curiously inconsistent and maddeningly inconclusive, but somehow, the soft spots are also the most compelling.

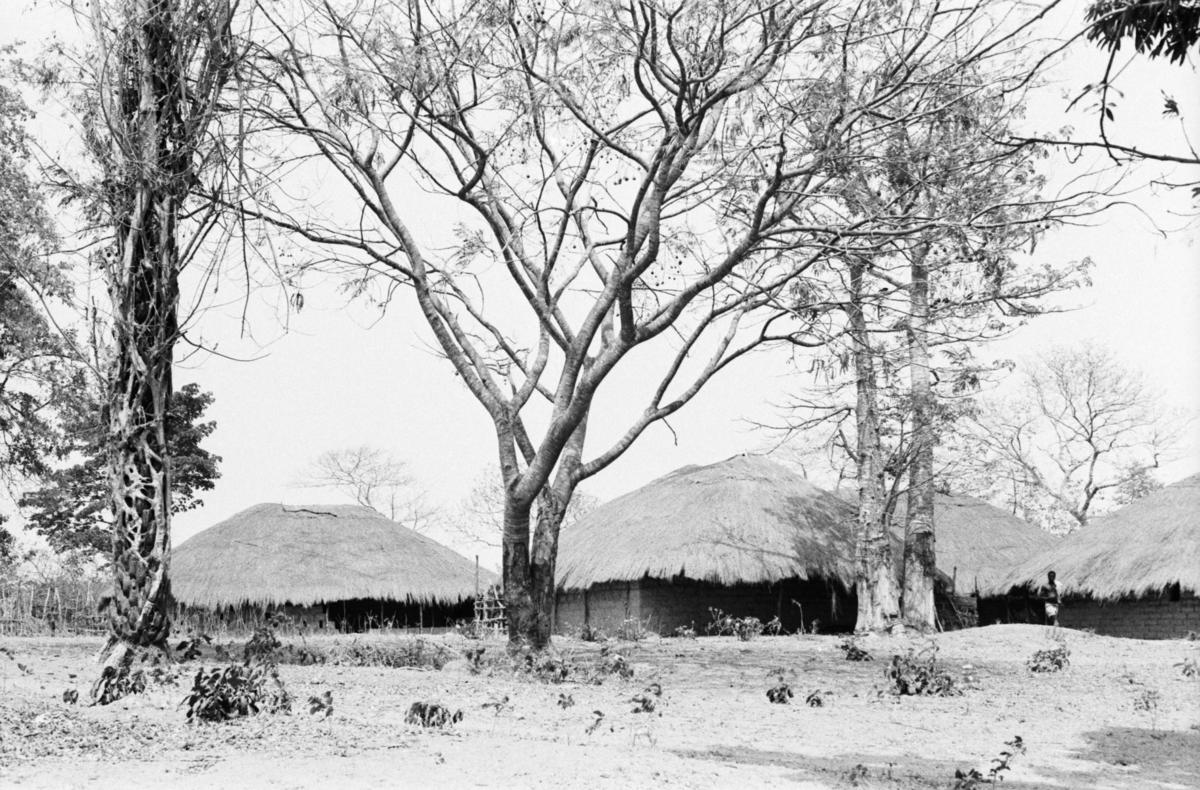

The film was called Guns for Banta, directed by Sarah Maldoror. Born Sarah Ducados in France to a family from Guadeloupe, Maldoror moved in a circle of revolutionaries and was actively engaged in the armed struggle against colonial rule in Africa; her nom de guerre paid tribute to one of Surrealism’s forebears, the darkly comic anti-hero of Lautréamont’s poetic novel Les Chants de Maldoror. In 1970, Maldoror began shooting Guns for Banta on an island in the Bijagós archipelago, off the coast of Guinea-Bissau.

This was three years before Guinea-Bissau’s independence from Portugal, in a time of conflagration and war. This was also three years before the assassination of Amílcar Cabral, who was amassing arms and consolidating power for the PAIGC, a revolutionary movement that sought to join Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde in a federal, socialist state. Maldoror knew and greatly admired Cabral, who, in addition to establishing the PAIGC, had founded the MPLA, a like-minded revolutionary movement in Angola, with the poets Agostinho Neto and Mário de Andrade. Andrade, incidentally, was Maldoror’s lover and husband.

Maldoror had made her first film, the 17-minute short Monangambé, the year before. Based on a short story by the dissident writer José Luandino Vieira, it captures the early days of the resistance movement in Angola in an allegorical tale about a woman visiting her husband in prison just before he is brutally beaten by the Portuguese police. With a loose, languid style and a soundtrack by the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Monangambé was shot in Algeria, and supported by the National Liberation Front (FLN) and the National Popular Army (ANP).

For Maldoror, Algeria was the mother of the world. She lived there with Andrade, and the cinémathèque in Algiers was their school. The director, Jean-Michel Arnold, initiated the first pan-African film festival in 1969, and invited filmmakers from all over the world to present and defend their work. “We trained and were trained through criticism,” Maldoror told Ecrans d’Afrique in 1995.

As with Monangambé, the Algerian government financed Guns for Banta. This was relatively new. Algerian cinema had been synonymous with the revolutionary movement from the start. It developed through the mechanisms of the FLN, and almost all of the films produced in Algeria at the time dealt exclusively with the war of liberation. Maldoror had been the assistant director on Gillo Pontecorvo’s landmark film The Battle of Algiers, so she had something going for her. But for the FLN to support films made in and about liberation movements in Portuguese-speaking colonies was something of a stretch. An Algerian technical crew joined Maldoror on location in Guinea-Bissau.

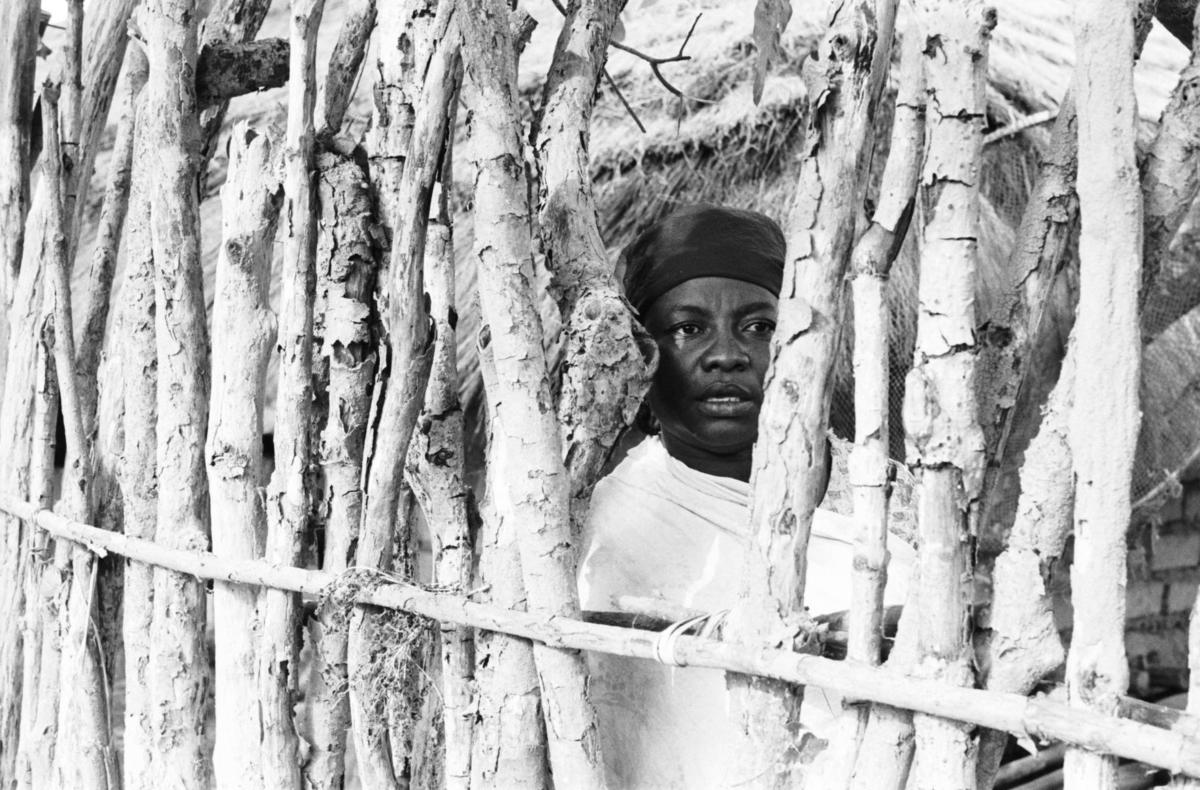

Maldoror assembled a cast of non-actors and guerrilla fighters, and worked from a spare script about a young woman named Awa, who joins the resistance after a party member arrives in her village and frames the struggle in terms of land and bread. She trains and fights and takes part in the ambush of four hundred Portuguese soldiers. When the colonial forces enact a bloody reprisal, she is killed. Or maybe there was a different ending. In two years, Abonnenc has located three different scripts for Guns for Banta, each with a different outcome, so he’s not so sure.

When it came time to edit the film, Maldoror clashed with the Algerian authorities (whether directly or through her handlers is unclear). She was doing Guns for Banta because she wanted to make the story of the liberation struggle known. But she also wanted to push a feminist point of view. “Wars only work when women take part,” she said in the interview with Ecrans d’Afrique.

“The role of women in the struggle is evident in Guns for Banta,” said Abonnenc. “Their political engagement was more obscure in Maldoror’s other films, but here, they really come into the fight.” Feminism was a tricky thing for the revolutionary movements of the 1960s and ’70s, not only in the context of decolonization in Africa, but everywhere. Class split one way. Gender split another.

Maldoror wanted creative control over her film. The Algerian government wanted the propaganda tool it had paid for. For Maldoror, she had lived the revolution, she had seen women carrying bombs on their backs, and she had the right to tell their story. The Algerian police disagreed and seized the film. For a politically engaged filmmaker who considered Algeria the heart of the revolutionary struggle (a war for independence that had actually been won), and the creative hothouse for the region’s cinema, this was a bruising betrayal. Maldoror left Algeria and stayed away for twenty years.

Ironically, that same year, Monangambé was selected for the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes. Soon after, Maldoror completed her second feature, Sambizanga, this time with funding from France. Sambizanga turned out to be Maldoror’s masterpiece. It won the Carthage film festival’s Grand Prize in 1972, and went into wide release in 1973. The New York Times hailed it as “a very fine film” and “a revolutionary picture.” The Village Voice praised Maldoror’s visual eloquence and capacity for capturing nuance. The critics anticipated great things to come.

Maldoror continued working — she has made nearly twenty films to this day, most of them documentaries about figures such as Aimé Césaire, Léon Damas, and Louis Aragon — but Sambizanga was her peak. Her career has been beset by irksome squabbles over who has the right to speak for authentic African cinema (the argument being that a French-Guadeloupian filmmaker does not) and the perception that audiences have tired of films positioning radical poets, painters, and playwrights in the middle of revolutionary politics, rather than to the side. Maldoror made three more films about Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, but none had the impact of Monangambé or Sambizanga, and who knows, really, what Guns for Banta might have been. A plan to make a documentary about Angela Davis fizzled. Maldoror hasn’t done much since the 1990s. Her legacy as a militant filmmaker — mining the same terrain as Flora Gomes or, for a time, Chris Marker — has vanished.

The backbone of Abonnenc’s practice is an abiding obsession with the Martinican revolutionary Frantz Fanon. When he was seventeen, Abonnenc found a copy of Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth in his mother’s library. He read the first chapter, “Concerning Violence,” and the last chapter, “Colonial War and Mental Disorders,” over and over again for a year. “I keep trying to understand Fanon’s radicality,” he said. “Glissant wrote that Fanon’s was a difficult path to follow.” When Abonnenc met Sarah Maldoror by chance in 2006, she reminded him of Fanon; he decided to follow her path instead.

Maldoror was giving a lecture in Paris on the poet Léon Damas. Abonnenc didn’t know Maldoror but he was curious about Damas, because he was one of the three founders of Négritude and because he was, like Abonnenc, from French Guiana. After the talk Abonnenc introduced himself to Maldoror and asked if he could see her documentary on Damas. They met and discussed this and other works. Now they are, in a way, friends. They talk often and visit museums together. Abonnenc’s Foreword to Guns for Banta is not only a complex study of Maldoror’s work; it is also a sincere effort to bring her back into circulation and give her the recognition she deserves. This sets Abonnenc’s current project apart.

Abonnenc has made a deal with Maldoror that if he finds the missing reels they will complete the film together. But Abonnenc knows he is chasing a movie that may turn out to be a myth. Though he has interviewed Maldoror for hours on end, the fact is that forty years have passed. She remembers some sequences from the film but not others. The most obvious thing for Abonnenc to do would be to go to Algeria at once and find out if the film exists. It says something about Abonnenc’s project that he is wending his way around Maldoror’s story slowly. Maybe he is gauging the distance; maybe he is building the fiction.

“For me as an artist, this is a very precise point,” he says. “All the people [Maldoror] met in Guinea-Bissau were liberation fighters, but the story of Guns for Banta is fictionalized. I really wanted her to tell me the story. Among filmmakers following the decolonization process in Africa, she’s unique. She was also the wife of Mário de Andrade, so in a way, she did this because she was in love. So the story is also about desire. But it took time. She’s reluctant to speak of certain moments that were tough. She’s been tricked many times. I am not working on dead pictures or past facts. I am working with someone who is alive, and my relationship with her is the core of the work.”

Foreword to Guns for Banta is an installation of accumulated archival materials arranged around a slide show of still photographs with a voiceover narration. The photographs, taken by war correspondents who were there when Maldoror was shooting her film, fill in for the missing reels, though gaps and holes remain. Some of the images come from other sources. “This is a way we work now, in 2011. We have so many pictures; we just have to find the places to search, and to ask, what can we say about all these movements now?” Abonnenc wrote the voiceover narration in three parts — the heroine of Guns for Banta, a filmmaker, and an artist. Read by three women, their lines intersect and overlap such that you repeatedly lose track of who’s speaking.

“It’s mixed up. You don’t really know who is talking. I wanted everything to blur. It’s not a testimony. Foreword to Guns for Banta is a way to produce a discourse,” said Abonnenc. Given the dire inheritance of so many liberation movements in Africa, as elsewhere, “What went wrong?” he asked. “This is a major question. There are so many things to connect, so many places and points of view. It’s incredible when you’re on this path.” But it must be tinged with a terrible sense of melancholy, too. All of the men who were in Maldoror’s orbit at the time of Guns for Banta are gone — Amílcar Cabral, Agostinho Neto, Mário de Andrade, all of them gone. The cause they fought for — hers as much as it was theirs — never really crystallized in the just or equitable society they were so committed to creating. Instead, revolutionary struggles gave rise to civil wars, appalling exploitation, and a politics of cynicism.

To meet Maldoror and sift through her memories is a rare occasion to revive the potential of that utopian moment as someone lived it. But there is also the risk that the moment itself will crumble as soon as it is exposed. “Foreword to Guns for Banta is a way of telling a story,” Abonnenc said. “It’s a way of saying: this exists, can we deal with it now?” If the aesthetic of Maldoror’s time privileged the image of the young heroic martyr dying for a revolution, the ethic of Abonnenc’s practice touches on the afterlife of that image — the militant who has lived long enough to look back and wonder why the first line of Fanon’s last chapter is still so apt: “But the war goes on.”