On December 12, 2024, the Lebanese artist Myriam Boulos (b. 1992) posted a photo of an AK-47 on her Instagram. The gun sits upright and slantwise in a floral-patterned armchair. Aside from the dark brown and black tones of the rifle and its army green strap, the picture is a study in ivory, from the painted walls and tiled floor to the plastic bag and paper coffee cups resting at the foot of the armchair to the small, rumpled book perched on one arm. The room has seen better days — the baseboards are mottled with water stains, the tiles have moss growing between them — but the image is somehow regal, the AK-47 assuming the air of a warrior with stories to tell. It is more a portrait than a still life.

The picture was posted four days after the collapse of the regime in Syria, but Boulos was careful to sidestep the political contretemps that erupted on social media in the wake of Assad’s fall. Amid starry-eyed endorsements of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham — the US-supported Islamist group that led the offensive — and tankie lamentations over this blow to the Axis of Resistance led by Iran, Boulos offered something different. “Please follow the work of Syrian photographers documenting their reality on the ground and outside of Syria too,” she wrote, in English, directing her followers to the account @al.ayoun, a self-described “space for Syrian storytellers, photographers, and filmmakers.”

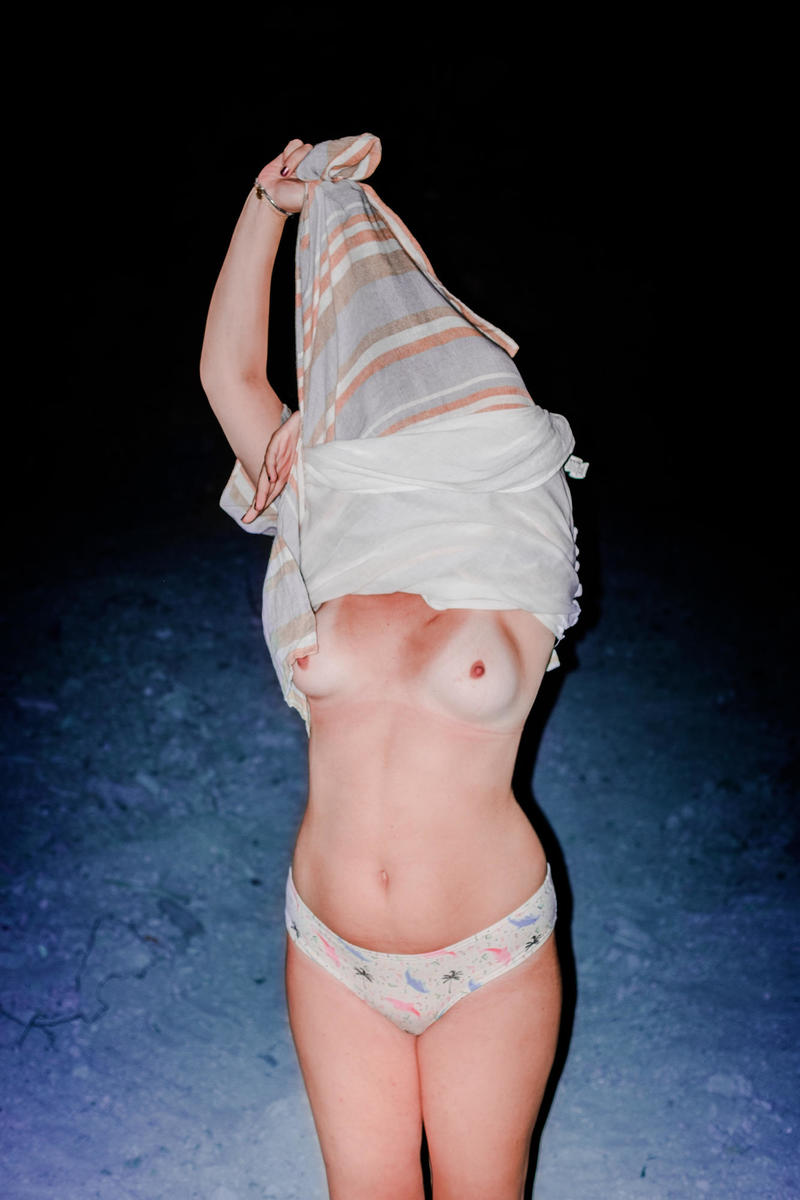

Boulos’s reference to Syrian photography as a site of “reality” is instructive. As her syntax suggests, this reality is not universal or invariable but keyed to the specific experience of each photographer, since a photograph is, famously, both objective and subjective. It is at once evidence and icon: proof that something happened, that someone was, and a social object invested with personal meaning, not just by the photographer or her subjects but by viewers, too. In Boulos’s work, the forensic and intimate aspects of photography don’t so much coexist as bleed together, such that any difference between news and portrait photography is obliterated. People at protests are shot as fondly — or as ravenously — as a nude, while nudes appear monumental, as if desire itself were a front-page story.

Boulos garnered widespread attention in 2020 for a suite of photographs in Time magazine documenting the aftermath of the Beirut port explosion in August of that year. A disaster tied to decades of political corruption and financial malfeasance, the blast unleashed a wave of devastation that killed at least 218 people and injured 7,000 more, displacing some 300,000 Beirutis. The explosion epitomized everything that plagues Lebanon, a diverse and dynamic country ravaged by its resident kleptocrats. Lebanon’s afflictions — including food and water insecurity and scarce electricity, often as little as two hours a day — are borne by all its citizens, but young people are disproportionately affected. (The country’s median age is 28.6, and the youth unemployment rate is just under 25%; the global average is about 16%.) Boulos photographed individuals in the ruins of their homes and workplaces, amid dust and shattered glass — and tear gas, during the street protests that broke out days later. Like hot air over asphalt, Boulos’s images shimmer with frustrated energy. Her subjects have everywhere and nowhere to go, life and possibility pulsing past the edge of the frame yet simultaneously choked off by it.

The cover of What’s Ours (Aperture, 2023), Boulos’s first monograph, shows two women kissing, hands clasping each other’s necks, one tongue sluicing the other’s mouth. The image’s near-mirror symmetry is broken by mundane details: the black elastic hair band that circles the wrist of the woman on the left, the birthmark on the other woman’s cheek and the tiny red scab on one knuckle, barely visible as her hand tucks under her lover’s shirt. In one of the short, diaristic passages interspersed among her photographs, Boulos writes, “Some people have said that my images don’t represent us,” and then, a page later, “Lebanon is so layered I still don’t know what ‘us’ means.”

Queer life is one of her main subjects — or rather, provocations. Boulos’s images eroticize subversion in a country where repressive laws prohibiting “sexual intercourse against nature” and cross-dressing remain on the books, despite glimmers of reform and more than one active queer scene. When I look at Boulos’s photograph of two men embracing, naked, against a gorgeous purple sky, one man’s hands resting protectively over the face of the other, whose hands coast down his lover’s ass, I think of a passage from the American poet Kay Gabriel’s A Queen in Buck’s County (2022):

In June I backed my boyfriend into a rail yard, piled his cock out of his jeans and jerked him off between the freight cars, on a bed of shale… We tightened in on each other, flush in case a window we couldn’t see cut through the canopy behind us. Did I mention the L train going by, or the cemetery behind it? We stopped close enough to see the graveside decorations, pink and plastic… I put my free hand on the small of his back, pressing with a couple fingers into the top of the muscles on his ass.

Boulos’s picture is a record of just this sort of sublime exhibitionism, fraught with the dangers of being seen and lit up by the pleasure of being looked at with love.

An inverse of this image appears early on in What’s Ours. It shows two women (maybe the women from the cover) set against rain-spattered glass — the rear windshield of a car, perhaps, or the front window of some café or bar — and bathed in red and green light. One woman’s head rests on the other’s chest, her arm held at an awkward angle, her closed fist hovering just above the other woman’s arm. Her eyes, lined in bold strips of black and silver, are half closed, her expression happy and drowsy, maybe after a long night of partying. With her wavy red hair and sleepy eyes, she resembles a figure from a Pre-Raphaelite painting, as does her companion, who stares directly at the camera, her face framed by her long black hair. She grips the red-haired woman’s shoulder in a gesture that looks comradely, steadying.

Unlike the male lovers, these women are fully clothed, their faces plainly visible. Their attire is vintage chic — a washed-silk blouse with cuffed sleeves, high-waisted jeans, a crushed pink velvet dress — and there, again, are the black elastic hair ties, worn around the wrist, and other details, like a small skull tattoo (it looks temporary) on the red-haired woman’s neck. What links these two images is the tenderness that saturates them, as well as the marriage of eroticism and decorum. Like her AK-47, Boulos’s couples — indeed, all her subjects — have a stately quality, and while her work is often compared to Nan Goldin’s, her tone more closely matches that of Chloe Sherman. Where Goldin’s subjects radiate vulnerability, Sherman’s images of queer life in 1990s San Francisco project confidence and hope. Her subjects seem to be stepping, however fleetingly, away from precarity, nudging pain into the background while they rejoice in the chance to exist as they are, to be seen as they see themselves.

Boulos’s portrait also recalls Two Women Disguised as Men, a well-known image by the late Lebanese photographer, Marie al-Khazen (1899-1983). Taken around 1920, the photograph features al-Khazen and her sister dressed in slim-fitting jazz suits, neckties, and Fez hats, sitting jauntily in overstuffed armchairs, a small side table set before them. Pictures of bourgeois women dressed à la garçonne were not uncommon in the Middle East of the early twentieth century. The scholar Yasmine Nachabe Taan suggests that the female body in such images becomes “a rich field for tracking the ambiguities of the modern,” a means of enlarging the contours of gender and sexuality and of mediating between traditional and cosmopolitan cultures. Boulos’s women aren’t dressed as men, but they nonetheless suggest a twenty-first century inquiry into a historical problem: how to celebrate sexual freedom and permissiveness without defining them in Western terms.

As Ali Behdad writes in his indispensable book Camera Orientalis: Reflections on the Photography of the Middle East, Orientalist photography in the nineteenth century often featured “harem scenes,” in which unveiled women were posed together in tableaux suggestive of the “boundless pleasure and perennial lasciviousness” that the colonial imagination associated with the Arab world. Today, the West prefers to think of Arabs — queer and female Arabs, in particular — as markedly unfree, persecuted by religious fundamentalists and savage theocracies. (Benjamin Netanyahu played on this trope when he mocked the resistance slogan “Gays for Gaza” as being equivalent to “Chickens for KFC” in his July 2024 speech to the US Congress.) Boulos’s images give the middle finger to Western assumptions about the Middle East as a place where LBGTQ people are uniquely imperiled, but they also intervene in a much longer history of Orientalist mythmaking, insisting on a multifaceted Arab femininity — and an equally complex Arab queerness — that is independent from, if still legible to, a Western gaze.

Boulos’s work never shrinks from the contradictions of modern Lebanese society. A pair of white jeans, splotched with reddish stains near the crotch, are described as Boulos’s own, shot “after a march against sexual harassment.” The stains look like menstrual blood, but Boulos doesn’t say, instead quoting a friend who saw a man set himself on fire, “because he was hungry.” A pat reading of this juxtaposition would insist that it is meant to underline the inseparability of women’s rights from human rights — that the Lebanese people are united in a struggle that fuses historically novel ideas (women should be free from sexual harassment) with more basic demands for food, shelter, and the like. A more subtle reading might suggest that Boulos is interested in the tensions among modern Arab feminism, anticolonial sentiment, and a national culture that remains strongly patriarchal.

Her images of protests, uprisings, and riots tend to focus on men; their bloody torsos and masked faces are lovingly captured, their rage and desperation matched by the delicacy with which they are shown touching, holding, clutching at each other. But feelings of solidarity can vanish in an instant: celebrating New Year’s Eve in Beirut’s Martyrs’ Square, ground zero for Lebanon’s 2019 anti-government protests, Boulos was taking pictures of a group of men when they turned and sexually assaulted her. “I went from smiling at them to screaming and shouting at them,” she writes.

Like Lebanon itself, Boulos’s work is a space in which you can find young women flashing their bras in the street next to hijabis running from tear gas, men making out with each other and men in balaclavas breaking glass windows. Sometimes these are the same people. What you will not find here are platitudes, whether visual or ideological. Nothing is stable; everything is agon. Each photograph is dialectical , embodying the paradoxes, incongruities, resentments, and aspirations of a population on the brink. Roland Barthes once said that the photograph is a record of the that-has-been, but for Boulos it is also a promise of the what-might-be. It finds in the present the glimmer of a possible future — hot, horny, exalted, free — and asks that it be remembered, insists that it is here.