Istanbul

8th Istanbul Biennial: Poetic Justice

Various venues

September 20–November 16, 2003

The Istanbul Biennial has ventured a leap into the elite international league — but at what price?

The dazzling city of Istanbul, framed by the Golden Horn, the Bosporus and the Marmar Sea, played host once again to the Istanbul Biennial. Situated at the crossroads to Asia, Istanbul became the meeting point for 85 artists from 42 countries, enticing art enthusiasts to enjoy the beautiful surroundings of this new hotspot for eastern art exhibitions. The continental crossover has played a significant role in Istanbul’s history, putting a unique stamp on the city. The character of Istanbul invites one’s imagination to leap between the East and the West. This connection between eastern and western elements, so often considered incompatible, seems effortless here — at least upon first glance.

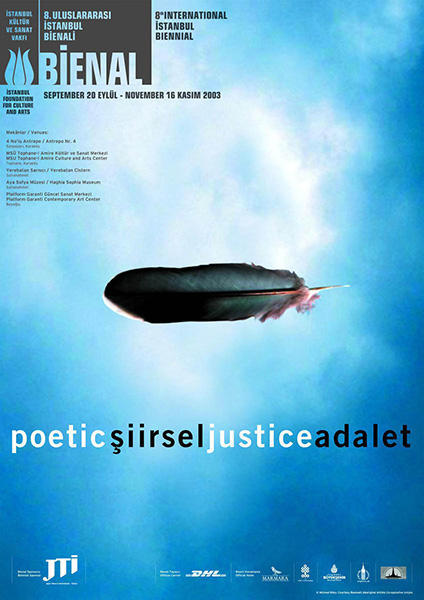

Compared to previous Biennial shows, what immediately became apparent was the increased number of art critics, curators and cultural journalists who flooded the city during the opening week of the event, due to Istanbul’s growing stature as “the city to be,” gained over the last few years. Perhaps even more significantly, the Istanbul Biennial has carved a reputation which can no longer be ignored. This year’s poster featured the theme “Poetic Justice,” and was flaunted at the entrance to the main exhibition hall on the harbor side of Karaköy. However, the allegory of this theme — the weightless feather of a dove lost in the midst of a blue sky — poses various questions in terms of what the artist is trying to tell us. Poetics — meaning light and free as a feather or lost in space? The plume of a true poet who is able to show us a way out of misery and leads us to a freedom which is just — but justice for whom? Does the combination of the terms describe a just poetry — or a poetic justice?

These questions may lead us down a rabbit’s hole. Nevertheless, once an exhibition is framed in a metaphorical way, as the curator Dan Cameron has done, things tend to become problematic. Through this curatorial superstructure, not only Dan Cameron but all the artists and visitors involved fall into the same trap:the search for a form of justice which is universally valid. Unintentionally, many presentations merely meet one another within the confines of a bubble. The title “Poetic Justice” hovers with pregnant meaning over the exhibition while at the same time hanging a Damocles’ sword over the artwork. And as hard as the viewer may try, she is not able to remove the tinted glasses that this title has placed before her eyes. She may try to study the works with concentration, squint her eyes together or take a step back from the piece she is regarding, but in the back of her mind a nagging question always seems to crop up: What is the link to justice? Once the works are judged in terms of their “poetic justness,” the “poetic” tends to quickly fall away. And then only “justice” remains in its condensed form, fluttering down at the spectator’s feet. It may very well be that Dan Cameron was cunning enough to understand this as the process of “poetic justice” in a figurative sense: the impossibility of a truly unbiased contemplation and therefore its non-existence; a synonym for the impossible search for “justice.” TO what bar can justice be measured against in light of its daily infringements, the misuse of the term itself and its continually expandable interpretations? An extremely vague interpretation …

But Cameron has not done any favors to the artists being shown under this title. Despite the fantastic quality of many of the exhibition rooms and interesting presentations, many of them appear to be isolated or even lost within the space. This particularly applies to works that, while attempting to deconstruct the subject of “poetic justice,” merely remind one of a quiet echo to bygone times and are left sitting in the room without fully taking shape.

Such is the case with the video piece Surrounded 2003 by Danica Dakic (Bosnia-Herzegovina/Germany), placed on view in the historical rooms of Tophane Amire Cultural Center, a former war and cannon manufacturing facility and barrack, first constructed in 1451 and now converted into an exhibition space. A 20 minute film loop runs on a screen attached to the ceiling of the room. Within the inviting darkness of the historic exhibition room, the light of the video work entices the viewer onto a circular, velvety mattress. One perceives various voices filling the room in alternating intervals projected from several loudspeakers. Lying back and staring at the ceiling, the spectator gazes upon a scene which takes on the appearance of a holy apparition: six naked figures as God created them — men and women of various colors — gathered in a circle and filmed by a camera rotating clockwise. Face forward, they crawl on all fours towards the circle, where they crouch over a book and begin to read. What the audience hears are passages from the holy scriptures of the six main religions.

Any initial pleasure upon viewing this scene is quick to pass — what remains is the sense of having been deceived. Something has been glossed over: unclear religious elements have been removed (the depiction of naked humans symbolizes the origin of mankind; in their bareness all people are equal). This is combined with hippie and pop art quotations from the 20th century (John Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance” and Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream”), blended together into a tidy television commercial using the most convincing advertising aesthetics. The “United Color of Ben” … sends its regards! Maintaining a balance between intellectual sophistication and pleasing one’s audience is always risky.

But there are also counterexamples. The exhibition’s concept functions best with those works that are developed freely from the task at hand. A good example is Emily Jacir’s (Palestine) “Where We Come From,”1 a piece originally developed for her own community. Jacir examines in quiet fashion the idea of what wishes she can grant to her compatriots who aren’t able to travel to Palestine, either because of possessing the wrong passport or having none at all. Within this context, Hana (born in Beirut to parents who fled from Haifa) asks Emily to travel to Haifa and play soccer with the first Palestinian boy that she meets. Abdulhadi (born in Kuwait, parents from Abu Dis, East Jerusalem) asks her to eat knafa from Jafar Sweets in Jerusalem. And then there is Mohannad (born in Cairo, parents from Jerusalem) who requests Emily to light a candle upon witnessing the first rays of sunrise over the beach in Haifa.

Equipped with a camera, she investigates these wishes and documents their realization. In her presentation, each photograph is accompanied by the written request as well as brief biographic data of the person involved. “Where We Come From” is an installation of photography and text which achieves its own form of reduced poetry. This is a quiet, personal pictogram of Palestinian history, the restrained quality of which stands out agreeably against the surrounding cacophony of loud and attention-grabbing pieces. It is also one of the few exhibitions in this Biennial which comes close to achieving “poetic justice.”

One may suspect that the inability of some works to speak to the viewer stems from a lack of communication between artist and curator on the subject of “poetic justice.” In talking to the young artists, a general dilemma surrounding overambitious exhibition concepts was confirmed: the lack of time as well as the large number of participants made a creative exchange between them impossible. Contact was limited to a written invitation from the curator. Discussion did take place about whether it really makes sense to compete in an artistic league that includes Venice and Kassel — or whether Istanbul should reorient itself completely.

Where does the Istanbul Biennial stand today? After the experiences of the last 16 years, it certainly seems plausible that the Biennial has achieved its goal of international art show status. never before has the Biennial attained such a high level of media interest and discussion in international trade magazines. So it comes as no surprise that the who’s-who of the self-proclaimed curatorial elite were flown in. Befitting the theme of the Biennial, the panel discussion entitled “Justice and the Creative Art” included Carolyn Christov-Bakargiew (curator and writer, chief curator at Castello die Rivoli Museo d'arte Contemporanea, Rivoli, Torino), next to such luminaries as Christian Haye, Vasif Kortun (Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center, Istanbul) and Professor Ute Meta Bauer (Founding Director of the Berlin Biennial for Contemporary Art, Office for Contemporary Art, Norway). During the podium discussion, which was surprisingly free of content and does not deserve and closer rendition, panelists examined the age-old question of whether art merely serves itself or carries a social responsibility. One advocate of the ‘pure’ art message (l'art pour l'art) was the New York curator Christian Haye. He maintained that art should not be burdened with the dilemmas created by politicians, and went on to say that art only serves itself and should therefore simply be allowed to exist, free from expectations.

The fact that Dan Cameron does not entirely share this opinion can be seen not only in the title — even if contested — of this year’s Istanbul Biennial. It also becomes clear after having worked one’s way through his eight page preface to the catalogue. In addition to statements about art and its responsibility to society (“The role of the artist is to call attention…”), he uses this platform to support his personal opposition to American politics. His text is framed by contributions from prominent, open-minded thinkers such as Arundhati Roy, including a wonderful excerpt taken from her last book, Power Politics. This writer and activist from India discuss the privatization of her country’s energy sector and the politics of writing. Here, powerful governments and their corporations become the modern Rumpelstiltskin, the potentate, powerful, pitiless and armed to the teeth.

Significantly more controversial than the official podium discussions at the Biennial was the theme discussed at an event hosted by the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). With a workshop series entitled “East from Europe,” the Turkish section of the AICA directed its energy towards young curators and art historians from more eastern regions — that is, eastern from the viewpoint of Western Europe. The young representatives from countries such as Lebanon (Sandra Dagher), Egypt (Mai Abu El Dahab, Khaled Hafez), Greece (Efi Strousa), Serbia-Montenegro (Zoran Eric) and Georgia (Tea Paichadze) exchanged their experience and insights while debating on the side about issues surrounding the current Biennial. All were unified in declaring both the title of the exhibition problematic as well as the reduced participation from artists in the region named above. Levent Calikoglu, one of the representatives of the Turkish section of the AICA, pleaded for a stronger integration of the Biennial in regional environments, with all its associated challenges. Despite the Biennial’s reputation and international inclusiveness, the status of Turkish artists has barely changed, according to Calikoglu. Although a select few have achieved the leap into international recognition, not much has changed for local artists. What is the sense and purpose of a Biennial in Istanbul: securing an international audience or securing stronger integration into the regional environment? Artists from non-European regions are still branded with the stigma of gaining recognition primarily as representatives of their home countries, and not for the uniqueness of their art itself.

This position also received support from independent Turkish artists, such as representatives from the group “Oda Projesi,” an artists’ initiative in Istanbul, which seeks a stronger exchange with artists from the Near East and hopes that the cautious process of convergence can be accelerated. A stronger reflection of the political and social environs was also requested by the Lebanese gallery owner Sandra Dagher — especially in a city whose neighborhoods have just recently been coming to terms with terminology such as “justice” and “terror.” But as the curator Mai Abu El Dahab (Cairo) formulated in her closing remarks, despite this critique, it must not be forgotten that the reality in Egypt as well as in most other countries of the Near East makes it extremely hard to offer a Biennial of an equivalent artistic and organizational standard. “Let’s not kid ourselves — we would be overjoyed to host a similar Biennial!”

From a political perspective, weak regional integration of the Istanbul Biennial can only be expected. Istanbul — less of a bridge between the Orient and the Occident and more of a springboard towards the West? Beginning with the legacy of Attatürk’s work towards integration within the European Union, Turkey has not necessarily been sending positive signals towards its eastern neighbors. Similarly, the government’s tortured decision-making process during the second Iraq War has clearly shown the precarious balancing act which Turkey is forced to maintain: on the one hand, the desire to ally itself more closely with the West, and on the other hand, remaining a good eastern neighbor. With a majority Muslim population, Turkey’s tightrope walk will continue to be a very difficult venture. Certainly the geographic position of Istanbul, as well as its democratic situation, offers the city the chance to serve as a bridge. But little in this direction can really be perceived yet. However, with encounters such as the one made possible by Beral Madra with the AICA event, first steps have certainly been made. These could give wings to the Istanbul art scene for further leaps between the East and West.

1 Installation with 32 mounted photos of variable sizes, 30 framed texts and 1 American passport.