In 1974, the children’s publishing house Dar El Fata El Arabi was launched in Beirut. Over the next decade, Dar El Fata — staffed by artists, designers, and writers devoted to bringing attention to the Palestinian cause — produced some of the most visually striking and progressive children’s books in the region. Bidoun sat down with Mohieddin Ellabbad, one of the cofounders of the publishing house and its first and most influential art director, as well as Nawal Traboulsi, a leading expert on children’s literature and reading habits, who got her start as an amateur illustrator hand-picked by Ellabbad to work with him making books.

Mohieddin Ellabbad: I remember the first time I walked into the Dar El Fata offices. Right away I noticed how plush the office was — wall-to-wall carpeting, a long row of telephones, fresh coffee and orange juice. I had come to Beirut under the assumption that conditions would be very difficult. In Egypt we had a fantasy that all things Palestinian automatically meant suffering. I imagined I would be sleeping in an iron bed with six other people in the room. But I was willing to suffer considerably for the cause. I had just scrapped a long-planned sabbatical in Paris, in which I had invested all of my savings, to come to Beirut and work with a novice publishing house linked to the Palestinians.

My first meeting was with Nabil Shaath who was the director of the Palestinian Planning Center and also in charge of the publishing house. He was also a member of the Revolutionary Council of Fatah; later he would hold various positions in the Palestine Liberation Organization and the Palestinian Authority. In Shaath’s office, I immediately noticed a stack of typewritten papers on the corner of his desk. In response to my inquisitive look, he told me that it was material he had approved for publication, and proceeded to dramatically ask one of his aides why it had not already been sent to the print shop. Another employee interjected that it was necessary to first design and prepare the manuscript. And of course, there was no designer. That was how I came in.

Nawal Traboulsi: Dar El Fata was the PLO’s cultural program, though there was no direct political guidance. Dar El Fata was very creative and progressive, although of course there was a definite, and genuine, enthusiasm for the Palestinian revolution. But the money came from the PLO.

ME: Actually, that’s not true. The money came from private businessmen. At the time, it was common for projects like this to be launched with private donations. But it was founded by Abu Ammar — Yasser Arafat’s nom de guerre — after Black September and the expulsion of the Palestinians to Lebanon. An Egyptian doctor who had been imprisoned by Nasser in the fifties, a Marxist, donated a sum of money to Fatah with the suggestion that it be used to fund something that would signify the revolution’s persistence — its ability to take the long road when necessary. A document for the education of children was being drafted at the same time, and thus the idea of launching a publishing house geared toward making books for children started to gain currency.

NT: I was twenty years old, and I was studying philosophy at the French university in Beirut, drawing on the side as a hobby. I had some work in an exhibition at a cultural center in the city, and I was very lucky that Ellabbad saw it. Though they informed him that I was only a student, he insisted on meeting me anyway. He asked if I was interested in doing drawings for children’s books. To be totally honest, at the time I had never done any drawings for children. What’s more, he said that the publishing house was to be primarily about and for Palestinian children, and at the time I had no relationship to Palestine or the Palestinians. But Ellabbad told me not to worry, he would guide me in the process. And in fact, he was so authoritarian! We called him Monsieur Millimeter because of his sharpness and precision. I ended up illustrating around ten books. I got to meet artists like Nazir Nabaa, Kamal Boullata, and Helmi El-Touni. All these Arabs then living in Beirut, “foreigners.” For a Lebanese French-speaking student from the 1968 generation, Dar El Fata opened my horizon onto the Arab world. I was interested in where they came from, their conversations, their painting. But I preferred to stay in the shadows.

ME: When I started, it wasn’t clear what we were going to do. There was no marketing or distribution plan. I decided that if the publishing house was to survive, I’d have to come up with one. What soon became clear was that we needed to establish several distinct series for various ages, in different formats. I made our official goal to publish sixty-seven books by the end of that first year. It was a large but necessary number. We needed to have an extensive and diverse back catalog for the publishing house to establish itself, and to find retail outlets in the Arab world willing to carry our books. I had arrived in May 1974, and I wanted sixty-seven books by December. It was crazy. Somehow we actually, miraculously, met our target.

NT: Yes, and you managed to publish original works! At the time, the few existing children’s publishing houses were busy translating already published books and copying their images. Even more impressive was that you published modern texts about modern children, the children of the 1960s and 70s. Furthermore, Dar El Fata was an Arab publishing house with authors and illustrators from every Arab country, which was a totally new and progressive practice. It was not a publishing house that merely reflected the owners’ tastes, as is common now, and at the same time it was not the property of any one country. Because it was dedicated to the Palestinian cause, which especially at that time was the cause of many Arabs, it was truly a pan-Arab endeavor. And it paid attention to children. Writing and publishing quality books for children was not common or trendy in those days — to even think about children was revolutionary!

ME: After the first year we conducted an internal assessment that pointed out the utter failure of our administrative and distribution system. What I suggested as a remedy was to become a much smaller operation, a sort of atelier de création, focusing only on the production of content. Nabil Shaath was very unhappy with my proposal, he wanted us to be something big, like Akhbar El Yom, the Egyptian newspaper giant, with their huge nine-story building. He wanted to be a big corporation that produced video for broadcast. I thought, “We can’t produce a sixteen-page book for children and distribute it properly.” He tried to convince me to stay, but I decided to leave after the second year. I returned to Egypt after the civil war erupted. Two of the office boys had already been killed in the fighting. But I did keep working with Dar El Fata through a project that I initiated in Cairo, the Arab Workshop for Children’s Books. We coproduced several books together.

NT: After Ellabbad left, nobody from Dar El Fata contacted me again. So it was a brief but influential two years for me. It was clear how crucial Mohieddin Ellabbad had been to the project. He was demanding about which artists he chose to work with, and he refused to have any artists forced upon him because they were Palestinian, or had certain political convictions. I remember that I was astonished to find that I was being paid exactly the same as other illustrators, although I didn’t consider myself a professional like they were. Ellabbad told me that he paid for the work, not the “name” of the person. It was a new and fair way of dealing, and I was proud to work in an institution that operated under such rules. Ellabbad gave Dar El Fata its Arab face — he made sure that it didn’t just become another tool for propaganda. He sought out writers and artists from Sudan, Morocco, Yemen, everywhere in the Arab world.

ME: To ensure my independence, and in order to keep the administration from interfering too much, I consciously made a point of doing my work away from their offices. I would keep the entire process under my control until I presented them with the final results. At this time, Hegazy, Adly Rizkallah, and Mahmoud Fahmy all came from Cairo and stayed at my house — four beds in a row, we lived and worked together. We worked so hard that we didn’t really have a chance to experience the Beirut you hear about, the Beirut of nighttime pleasures and good food. When we Egyptians went to Beirut in the Seventies, we made a bigger impact than is usually acknowledged.

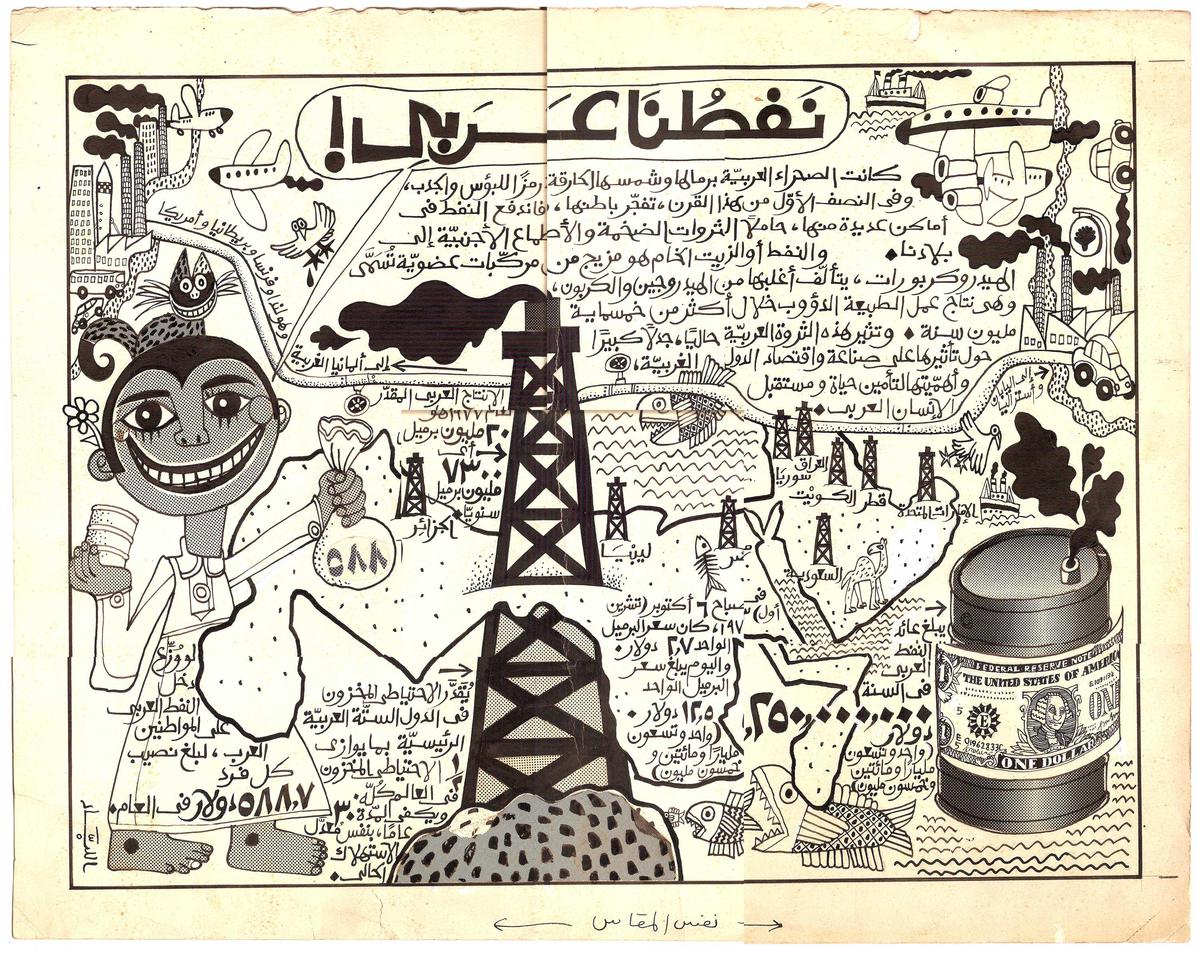

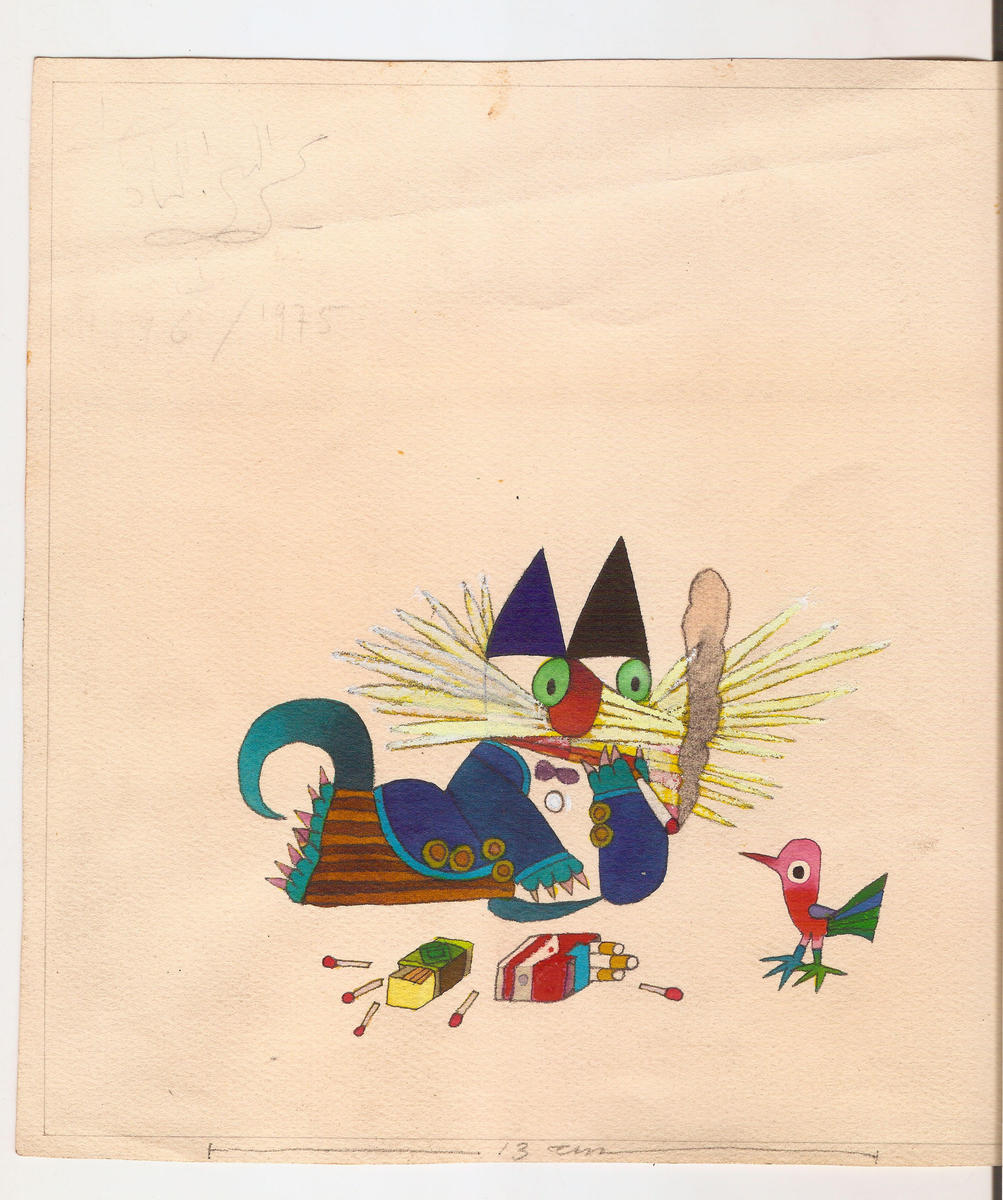

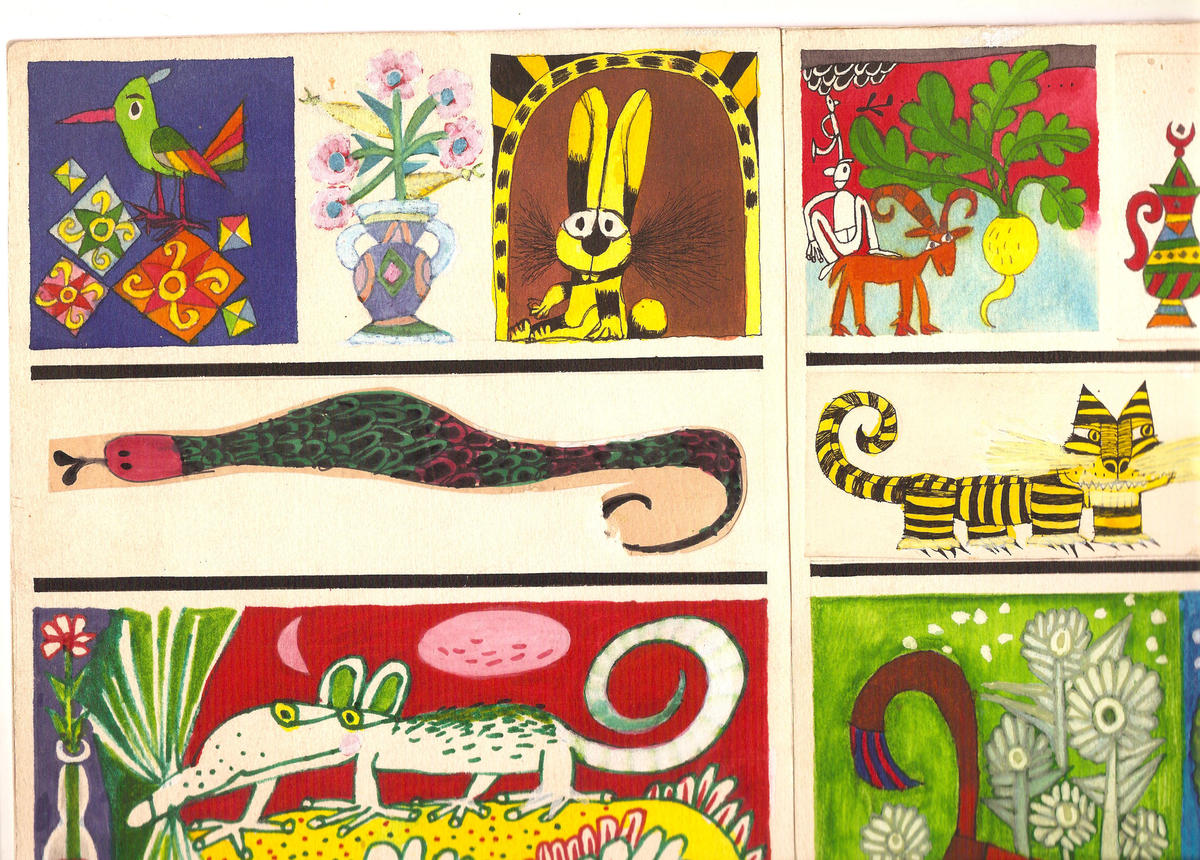

One thing I remember unconsciously doing was to use the publishing house’s catalog as an opportunity to publish a visual manifesto of sorts. I collected different drawings and juxtaposed them to produce a cover for the catalog that represented the kind of visual world we were interested in. We got rid of Mickey Mouse and Tom & Jerry type drawings. The idea was to present a new “rough” aesthetic that was at the same time visually powerful and artistically complete — something that was local and that rejected the sentimental and bourgeois nature of the dominant form of illustration at the time. What we wanted were rats, dogs that looked like the ones you see walking down the street, cats smoking cigarettes. That was what I was looking for, not to be just driven by the demands of creating images for propaganda. Anyway, everything I suggested was accepted!

NT: I remember during the civil war a meeting that Mohieddin and I participated in where some colleagues voiced the opinion that instead of drawing killings and corpses we should be drawing optimistic and hopeful things. I was quite critical of this position, as I believed we should be drawing what’s around us, the terrible reality we were living. I had also become involved in the Palestinian cause by that point, and I agreed with Mohieddin that art should exceed reality so that the audience could register reality itself. The whole period was marked by revolutionary ideas everywhere.

ME: Dar El Fata being connected to a political organization still meant that there were pretty sticky situations sometimes. People I had never seen before would suddenly show up and stand there, watching us while we were working. In such situations, I tried to be both polite and firm. After the customary but curt greetings I would find out who they were, usually people from the Palestinian Planning Center, on some kind of investigation to find out what we were up to exactly.

In 1975, the Emirates paid for the media campaign that accompanied Abu Ammar’s historical address to the UN, and suddenly there was funding for us to do something cultural to accompany his trip. The decision was taken to translate a few of our books into different languages to demonstrate the kind of books Palestinian children were being exposed to. The mere existence of a children’s publishing house was already an achievement, but fortunately the books chosen were of an aesthetically high standard, not mere propaganda. But the problem with the administration was that they couldn’t always differentiate between propaganda and art. Our efforts were always bound up in propaganda, so in a sense we never fulfilled our true potential.

NT: Another artist and I made a postcard for the tenth anniversary of the Palestinian revolution. The image was also published in the An-Nawar newspaper, but it was attributed to a twelve-year-old Palestinian girl called Nawal Abboud, who didn’t exist. Although I felt like the Palestinian girl secretly existed inside me, like another secret me, and though I was happy that my work was selected and used for the Palestinian cause, as a poster and as a background for a Palestinian children’s play, it was ultimately an act of theft that didn’t respect the artist’s rights. But I didn’t say anything. I have a draft of the original illustration, and it seems, in retrospect, like a prescient illustration of the children of the Intifada in the late Eighties and early Nineties.

ME: It’s important to note that the experience of working in such close proximity to a political machine also influenced my practice positively, because it mixed up all the different channels. I used to work as a designer, a cartoonist, and illustrator — after Dar El Fata I started exploring the possibility of mixing all these different strands. There was a story by Zakaria Tamer called The Cat’s Banquet that I designed the cover for. At the time I was doing lots of caricatures about the infitah — Sadat’s economic open-door policy in the seventies — in which a vicious-looking cat is in the process of seducing a bird. I gave the cat a pack of Marlboros and a bottle of Coke.

This was the image of the enemy: extremely well dressed but with claws, like the West. Our original publications, while actually quite cheap, looked lavish. I felt that this was not fitting — to walk into a refugee camp with open sewers and to present such an expensive-looking book, which indeed cost 25 pt — a lot at the time. I did an analysis that showed that it was possible to produce a book for a quarter of the price, if we got rid of the cover. But that never happened. I also initiated a wall journal, in public, with spaces left for locals to fill in. We produced six of them. Other formal innovative and rewarding experiences include the work I did on a book by Zakaria Tamer, which was a sort of comparison between a free, wild horse and a domesticated, servile one. At the time, I came across an exhibition of paintings of horses in Yemen by Laila Shawa. So I asked her if she would like to illustrate this book for me. When she hesitated, I told her that we could do the book together. I said, “You do the paintings in whichever form you like, and just leave me some space for the text.” We laid out the book together, and it was really beautiful. I was always interested in finding new unknown or unprofessional artists who had something strong about their work. Like Nawal, Laila had just graduated from university and had a wonderfully free and naive style. But you need time to discover people, and time to work with them. Unfortunately, things were run quite erratically, and we also worked with people who were not really able to go beyond the dominant aesthetics of the time. Also, the goal of producing sixty-seven books that I had set for the publishing house dictated some of these choices. Sometimes you are not as big as your dreams, and the people you’re dealing with are not up to it. And maybe I wasn’t able to achieve the aesthetic criteria I had set forth in the manifesto.

NT: For me, my experience with Dar El Fata and the war afterward put me on the path I am on now. At the time it was part of a general ambience of revolutionary movements. I am from the generation that dreamed of creating a new world, a new Lebanon as a country of freedom and rights for all citizens, independent of religion, gender, or social class. The war went on to destroy everything in my life, but my work at Dar El Fata was the seed of everything I am doing now. For over ten years I have been engaged with children’s literature, libraries, and public reading. I’m one of the founders of the first NGOs in Lebanon to focus on the establishment and development of public libraries. Right after the war ended, Rafik Hariri was rebuilding the country in a bourgeois way, and a group of friends and activists began working on how to find alternatives through which to reconstruct this damaged country. So we focused on children, public schools, and libraries.

ME: After I left Beirut in 1976, the publishing house continued until the Israeli invasion of Beirut in 1982, when it left with the mass exodus of the Palestinians. It then came to Cairo, and a significant change took place. I guess politics finally became absolutely dominant. I am only guessing here, but I think that the house acted as a secret channel of communication between the PLO and the Egyptian government, who at the time were not officially communicating. I continued to design some books, and did some stamps for them, like the now iconic Falasteen Arabiyya (Palestine is Arab) stamp. When Israel participated for the first and last time in the Cairo Book Fair, with a pavilion next to the Dar El Fata pavilion, we volunteered to hold different events to support the publishing house and to celebrate Palestine. Later on we discovered that the PLO had allocated a budget for these activities. I wonder where the money went. By then, in the mid-Eighties, it was really over. Every couple of years a book might be published. The house was finally closed down sometime in the early Nineties. No one ever called to let us know.