Sacred Heart Chaldean Church juts out like an overgrown shed on a street of abandoned shops with names like Happiness Club and American Store. Thirty-odd years ago, Saddam Hussein donated nearly half a million dollars to fund the church and the cultural center across the street, which now serve the largest population of Catholic Iraqis outside the Middle East. For years, the squat wooden church was a gathering place for new immigrants, many of whom had come to Detroit’s east side precisely to escape Hussein. The church’s pastor, Jacob Yasso, calls the former Iraqi president “a very generous, warm man who just let too much power go to his head.”

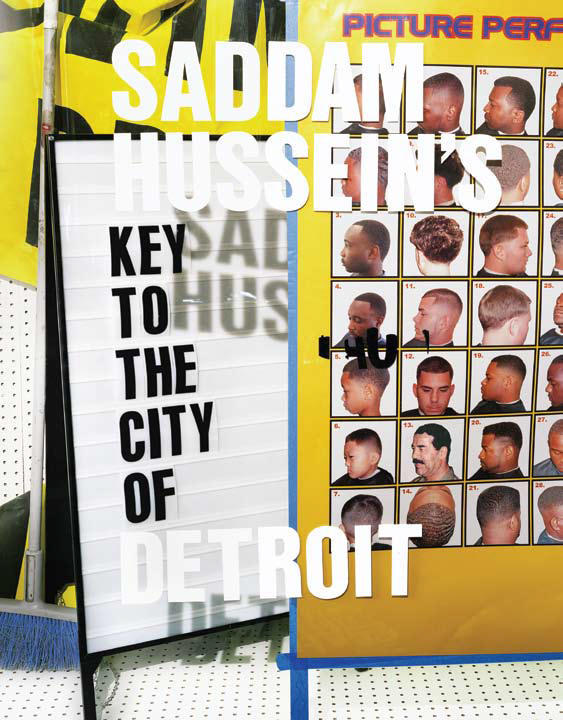

Yasso met Hussein in 1979 at a banquet in Baghdad, where the pastor gave a speech commending the president for his kindness to Christians. “Saddam was 100 percent American then,” he says. “He arranged for the government to pay for my trip and [for me to] stay at the best hotel in Baghdad.” After learning that Yasso’s Michigan parish was in the red, Hussein promptly wrote a check, the first of two, for a quarter of a million dollars. After Yasso’s triumphant return, an influential member of his flock convinced Coleman A Young, the controversial mayor of Detroit at the time, to give Hussein the key to the city.

Young, a cheerfully polarizing figure who had become the city’s first black mayor in 1974, displayed little interest in international politics — he had a habit of dismissing world leaders with names like “mean sucker” or “old prune-face” (though, to be fair, he also used that language on his suburban counterparts). Young handed out more than a hundred keys in his twenty years as mayor — he once called it a ritual “overbloated with meaning” — and it’s unlikely he gave much thought to making Hussein an honorary citizen. But the “dirty key” was important to many Detroit Chaldeans, who saw it as a reward for their hard work and a sign of their commitment to the city. “Young didn’t give a damn about anything outside of Detroit,” says Amir Denha, former publisher of the Chaldean Detroit Times. “The gift was for us, not Hussein. He was proud of us.”

Today there are 120,000 Chaldeans in southeastern Michigan. Like other Iraqis — indeed, like most of the groups that ended up here — Chaldeans were drawn to the area by the auto industry in the first half of the twentieth century. Though the majority of them no longer live in Detroit proper, they own most of the grocery, corner, and liquor stores in the city, having taken over the businesses from departing whites before and especially after the 1967 riots. They promote themselves as model citizens, patriotic entrepreneurs, and family-oriented conservatives. To make themselves appealing to their neighbors, the Chaldean community distributes a brochure to business partners, city leaders, and schools, touting their history and entrepreneurialism and featuring a collage of images of Chaldeans at work — a priest, a US soldier, and a supermarket owner reaching into his freezer.

Since the American invasion in 2003, more than half of Iraq’s remaining Christians have left, many of them bound for Michigan. There is talk of Detroit becoming a permanent Chaldean city-in-exile; area leaders have requested that the patriarch of Babylon protect himself by transferring headquarters, based in Iraq for over five hundred years. (He has declined, repeatedly.) Last summer, the Chaldean Mother of God Church purchased 160 acres from the city of Detroit to use as a summer camp for Chaldean children; on the grounds, a new church will sport a replica of a shrine to Saint Gorgis (the original is grafted into the side of a mountain near Mosul). This spring, the first-ever Chaldean museum is set to open, which will trace the people’s history from ancient Mesopotamia to the vacant strip malls of outer Detroit.

There is in all this an element of Chaldean exceptionalism. Most Chaldeans pointedly define themselves as not Arab; the language they speak — those who still speak it, at least — is Aramaic, “the language spoken by Jesus”; the Assyrians, their ancestors, are numbered among the earliest Christians, supposedly converted in the first century by the Apostle Thomas, on his way to India. (When The Passion of the Christ came out, some members of the Chaldean community were offended that reporters kept referring to Aramaic as a dead language; others complained about Jesus’s accent.) More ambitious Chaldean nationalists, nothing if not nimble, will tell you that their ancestors are both “the American Indians of Iraq” and the inventors of writing, astronomy, irrigation, the number zero, bronze weaponry, and beer.

Thousands of Iraqi refugees, many of them Chaldean, are expected in Michigan in the coming years. Jacob Yasso hopes the influx of immigrants will help reinvigorate his church, which is now attended almost exclusively by the elderly. But for Detroit’s old Chaldean Town, as for the city itself, the prospects are not good. Detroit’s population is down to the size it was in the 1920s, when the first Chaldeans came to America by sea.

Among the remaining parishioners at Sacred Heart Church, there is a sense of nostalgia that they acknowledge as desperate, even perverse. There hasn’t been such a fondness for Hussein for decades. Yasso speaks bitterly about the war and America’s unwillingness even to think about compromising with its former friend and ally. “Saddam was good for Christians,” he says. “Now he’s murdered, and look what happened.” He still keeps a framed photo above his desk of himself and other Michigan delegates handing Hussein the key. Yasso never found out what became of it. “Ask the US troops,” he laughs hoarsely. “Maybe they’ve recovered it in one of his palaces.”