Sometime in the middle of the 1970s, a glistening, barrel-chested, tri-colored robot of Japanese provenance entered the lives of Lebanese youth. Wing-like protrusions emerged from his incongruously teeny head like a set of bull’s horns. His arms were Herculean, substantial enough to hurl any enemy into a distant abyss, while his robot hands seemed always to be clenched into little balls of fury. On occasion, he would commune with a flying saucer, which allowed him to soar over the sky at light speed as he battled a malicious empire run by a galactic dictator named Lord Vega the Great and his equally malicious associates. The robot, the savior of humanity, was called Grendizer.

It was more than a little tempting to extend this tale into the lived world; Lebanon was in the midst of being torn into a million pieces care of its civil war, and later, by Israel, as that state’s forces marched into southern Lebanon in 1982. Grendizer’s text, translated from the Japanese to French, and then to Arabic, would call for the forces of good… To battle the infidels! To seek honor! To demand resistance! Indeed, the lines between Mughamarat Al-Fadaa, or “Space Adventures,” and real life became confused. Legions of children grew obsessed with Grendizer. They memorized the theme song, sung by a cheesy Lebanese pop star named Sammy Clark.

Like many members of his generation, Fadi Baki (inexplicably known to his friends as Fdz) cut his teeth on the giant robot, collecting his action figures and comic books. Grendizer was a crucial part of his subcultural education, a milestone on the road to nerd-dom. Years after the civil war had come and gone, after college at the American University in Beirut (AUB), and even after going away to London to study film, he and three similarly inclined friends came together to create a comic book of their own — in, of, and for Lebanon. One of them, Omar Khouri, had gone away to the States to become a painter. Another, Lena Merhej, had gone to New York to study design. And there was Hatem Imam, a shaggy-haired polymath who had also studied fine arts in the UK. By 2000 or so, the four of them were back in Beirut, communing in the cafes of Hamra and scheming their separate schemes. And then, like a band of heroes — or, perhaps, a Japanese robot — they came together to create an incubator for local versions of the pop-cultural products they’d imbibed as kids. Drawing from the world of superheroes, from science fiction, and from history, as well as the incomparable stuff of everyday life, their trilingual anthology of comic art was launched in late 2007, with some meager funds for printing, a lot of will, and very little sleep. Four issues later, the Samandal gang are still at it, plotting the conquest of the Middle East and teasing each other in the meantime.

Negar Azimi: Who was the biggest Grendizer head among you?

FDZ: That would be me. My first email address was dyezer@yahoo.com. My earliest memory was of the cartoon playing an hour after I came back from school. My watching ritual always involved me stuffing my face with something sweet. I’d either be neck-deep in a jar of Nutella or chugging my fiftieth Pepsi or whatever would drug me into sugary nirvana as Grendizer beat the shit out of other giant robots on TV. This conduct hasn’t changed much over the years. I played with the action figurines, too, the sugar blinding my rationale to the point where I’d shoot Grendizer right out our seventh-floor window to make a giant dent on our poor neighbors’ cars beneath. I have a clear memory of losing my favorite Grendizer toy at one of my mother’s hairdressers. I had a figurine that was fully articulated, with arms that could shoot out and a flying saucer that he could be inserted into, and I was using the salon’s various equipment to unleash giant robo-hell upon its customers. The hairdresser, a man called Mimo, was a towering militia-type with a jet-black Gandalf mustache and a frizzy Afro. He claimed that he was a Grendizer fan, too. As he surgically operated on my mother’s bouffant, we hit it off. I was proud of myself, a noisy seven-year-old with a budding camaraderie with an older man — especially when Mimo held up the figurine in admiration and demonstrated to everyone his knowledge of all of Grendizer’s weapons. When we finally left, Mimo gave me a wink and a Halls drop, and I was smitten. I was going to grow up to become a hairdresser. When I got home, my action figure was gone.

NA: Wait, do you think Mimo stole it?

FDZ: Yeah, a few hours later I realized that I didn’t have my action figure with me anymore. My mom immediately called the salon to see if it was there, but Mimo said it wasn’t. The fucker stole it! I still catch myself festering over that toy, boiling with the knowledge that somewhere Mimo’s mustachioed child is playing with my Grendizer instead of me.

NA: Okay, so who among you is the biggest comic geek, historically?

FDZ: That would be Omar.

Omar Khouri: I practically learned Arabic from comics. I read Grendizer, Batman, Asterix, Calvin and Hobbes, Garfield. I liked Superman, too. It was translated from the English. The pages were printed as mirror-images of the originals so that they could be read from right to left, as Arabic is read. So the “S” printed on Superman’s torso became a “Z.”

NA: What about the rest of you?

Lena Merhej: I read Loulou wa Tabouch, Samer, Glenat, and later L’association, the French comics. I had a boyfriend who was into them. I got into them again years later, when I was living in New York and I started writing to Omar. I wanted to keep a comic journal from New York, like Julie Doucet or Linda Barry. Before that I would read German children’s books at the Goethe Institute in Beirut. But I couldn’t speak German, and I guess this gave me the interest and later the motivation to “write” in images.

Hatem Imam: The first comic I read as a kid was Majallat Majid. I was living in Abu Dhabi back then. I read all of it, the comics, the letters to the editor, the submission guidelines, the text in the subscription call out… It was the only thing available to read.

NA: What about TV? Did you watch TV?

HI: It’s a completely different thing.

FDZ: You can’t take TV to the toilet.

HI: For me, comics were always related to bedtime. I read them there. I can only read them in bed. I’m pretty much the same now.

FDZ: I read while I’m on the toilet. I guess I had difficulty transitioning. I have a bookcase in my bathroom.

HI: But you don’t have any space in your bathroom! You can hardly fit into it.

NA: Tell us more about Majid.

HI: It was a mix of influences. I think it was published in the UAE by Al Ittihad Publishing House. Some of it was done by people in the Gulf. I remember one story clearly: “Moza and Rashoud,” on the last pages. I think it was actually illustrated by an English person.

NA: Were Moza and Rashoud lovers?

HI: No, they were “friends.” Actually it was pretty boring. Most of the stories were boring. All of them were mediocre, somehow. It was the idea of having a comic that was most thrilling. There was a section in the magazine where readers would fill in blanks of text and send in their submissions and win prizes.

FDZ: Did you ever write to them?

HI: No. I was lazy. But other people did. You could also write to all the characters. When they raised the price to 3 dirhams, people wrote in complaining. The characters would write back. There was one character I remember distinctly, called Kaslan, or “Lazy.” Anyway, Abu Dhabi was just really boring. I rarely left the house. Sometimes we went to the beach. School, which was all boys, was horrible, I had no friends.

NA: What was the typical storyline of a Majid story?

HI: It was pretty preachy. Like — it was no good to be kaslan. Bad guys were always losers. There was religion, too. Actually, there was one more exciting story, called “Shamss wa Dana.” I think they were stranded on this island and had a weird relationship to animals.

NA: Like, they had sex with them?

HI: Negar! No! Magid never had sex in it.

FDZ: How old were you, anyway?

HI: Twelve or thirteen.

FDZ: And you already had dirty thoughts?

HI: No, that was later…

NA: Fdz, what was your first comic book memory?

FDZ: For me, it came in phases. I was in Beirut until I was eight, reading Superman in English and locally produced Grendizer. I also read comics on the back of cornflakes boxes. Then I moved to Syria during the war. There were no cornflakes in Syria. So I stole Asterix from the library.

NA: Stole?

FDZ: Stole. The librarian trusted me, and I abused that trust. And then I finally came back to Beirut, and I remember the first MAD Magazine I saw. And I tried to read Arabic Superman, and my father was like, What are you doing? That was what I spent my pot of money on, Arabic Superman.

NA: Zuperman!

FDZ: I didn’t know it was translated! Arabic Superman was original Superman for me. They were translating stories from the golden era of Superman… with Krypto the Superdog. I only noticed later that in our version they covered the short sleeves, and they drank juice instead of booze.

NA: Who did the translations?

FDZ: It was done locally by Al Imlaq publishing house in Beirut. And it was out of order. That was the general problem in my childhood — all our childhoods, I guess. Bad serialization. It was all out of order! Same thing with television.

HI: Yeah, cartoons were just filler to the station, so, like, forty-five minutes into a show, they would just cut it off —

FDZ: — and you’d be devastated because you would have no idea what happened at the end.

HI: You know Jazeerat Al Kanz? Treasure Island. We would all go home at 6pm on Thursdays and watch it. They showed all of them except the very last episode.

NA: What about Grendizer, was that dubbed?

FDZ: Again, we never thought it was dubbed. It was just Arabic.

HI: It was proper fossha — classical Arabic.

FDZ: It was the most exciting cartoon on television. Giant robots, giant dinosaurs, explosions, everyone looking for their dead mother or father, high drama, post-apocalypse. What can compete?

HATEM: Remi?

FDZ: Remi!

HI: I hated that shit. For me there was Tom and Jerry. Except, whenever there’d be any flirtation between Tom and some female cat, they’d cut that out [in the UAE].

FDZ: And if they got drunk…

HI: They got drunk a lot!

FDZ: They would cut that, too.

NA: Wait, did you mean Remi Bandali?

FDZ: No, it was a Japanese program based on a nineteenth-century French story. The terribly depressing story of an orphan child sold to a mentor with dogs. A monkey and dogs that would get rabies?

HATEM: Yeah, it was depressing. Everyone dies, actually. In the last episode, Remi finds his mother and his brother, and his brother is a cripple, and they all live on a boat.

FDZ: That is pulled by two horses.

NA: A boat pulled by horses?

FDZ: Yeah. And in the last minute of the last episode, the horse runs, and the brother is in a wheelchair and it rolls into the river, and while he’s sinking, he’s looking up at Remi.

HI: It was sad, but we used to watch it anyway. There was nothing else.

NA: Did you watch Grendizer, Hatem?

HI: Of course.

FDZ: That show was awesome to watch. They got really good voice-over actors, like theater actors, and we had at least five years of really excellent dubbing. What’s the studio called? Studio Baalbeck or something. They had great voices.

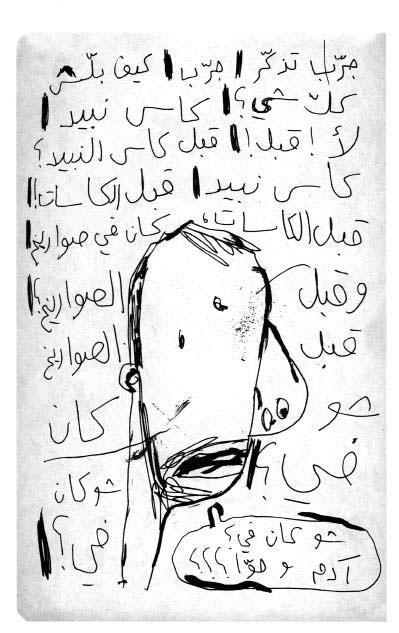

HI: And good names, too. “Oloolo” was one of the monsters.

FDZ: The T. Rex general of Satola’s Dinosaur Army!

HI: And they used fossha in exciting ways. Fossha was always related to geography and reading class and suddenly we had fossha — but talking about dinosaurs and robots. Which shows you the richness of the language. Fdz and I have long conversations in fossha. It’s great, you can find the weirdest adjectives.

NA: Why was it so awesome?

HI: It was just crazy. They would say things like “Oghrob an wajahi ayuhal waghed” for “Get out of my face, you bastard.” It’s a bit like making jokes in the language of the Qur’an.

NA: Language seems very important to you guys. As far as I can tell, Samandal is the first trilingual comic ever. Very Lebanese.

HI: We wrote Issue 3’s editorial in fossha. To me, it’s hilarious. We’re used to this kind of thing, encountering fossha in Grendizer or dubbed.

NA: Where did you get the idea for Samandal?

OK: I was working on this comic (“Salon Tarek El Khurafi”) in 2006 and wanted to publish it in Lebanon. It needed to be serialized, and there was no publisher here that did that with comics, so I thought I could give myself, as well as other frustrated aspiring comics artists like me, a periodical platform to show our work. I was reading a lot of Japanese manga at the time and was fascinated by their magazine formats, where you get about six hundred black and white pages a week of different comics, some serialized and others complete, as opposed to American comics, which are usually single issues of about twenty-four pages. I thought something similar on a smaller scale would be appropriate, especially since it would allow a number of artists from different places, using different languages, to mingle. The size of Samandal is also taken from manga, Book 1 of Akira by Katsuhiro Otomo-sensei. We also got a push after Hatem and I went to a talk by Jad Khoury at AUB. He had started his own comic for adults in the 1980s with some friends, Beirut 89. They had a collective called the “Jad Workshop” — him and his wife and some other people, who lived in the same house during parts of the war and produced this thing. So we went to him after the talk and explained our idea for Samandal.

NA: What was his response?

OK: He urged us to do it in Arabic. Beirut 89 had been in Arabic. And he had his doubts we could pull it off. He didn’t think we could get one hundred pages together!

NA: What is your relationship to a place like Egypt, where fewer people speak English, and even fewer French?

FDZ: You know, our first expansion would be to Egypt. One of the first reactions we got was, “You can’t do this Lebanese shit in Egypt.” But at the same time, people read us there. Well, there’s a huge readership of comics there.

HI: There’s a tradition of illustration, too. And then there was the whole children’s books thing back in the 1970s. There was a sense of the whole world being consumed by Arab nationalism, and you see that in the children’s books. Children were the future. Now there is something similar that binds us — but instead of Arab nationalism, it’s that we despise our own regimes and are fed up.

NA: What’s the relationship between children’s books and comics in the Arab world?

HI: All those guys, Hejazi, Mohieddine El-Labbad, Helmy Touni, they were producing comics for kids. Their work was often ideological, most of them were secular progressives.

FDZ: And you also had Dar El Fatah El Arabie here in Lebanon, too, a Palestinian publishing house that produced children’s books. Some of those artists were involved in pan-Arabism, the Palestinian situation.

HI: There was this book called El Beit (The House) that went around to international festivals and won awards. El Beit starts by saying that the chicken has a home and it’s called a coop, the horse has a home and it’s called a stable…

FDZ: … and the Palestinian has a home and it’s called Palestine — but wait! He doesn’t, really.

HI: And then you turn the page, and there’s an image of a Zionist, and he has fangs and is all green.

FDZ: Isn’t he in a tank? The Zionist?

HI: Really?

FDZ: There’s a Kalashnikov, anyway. And these guys were doing comics!

NA: But that generation of Egyptians was somehow important to you?

HI: Yeah. Labbad has a series of books that deal with visual culture, including one about hieroglyphics. He talks about Western comics — he looks at Tarzan, and it becomes a critique of colonialism. It’s the best writing on visual culture in Arabic I’ve ever read.

LM: My favorite book as a kid was The White Sail, and it was produced by Dar El Fatah El Arabie. I was mesmerized by the character drawn by Hejazi. And the boat was made out of a newspaper in the book. But I couldn’t even read it at the time. I only started reading Arabic for pleasure in my late teens.

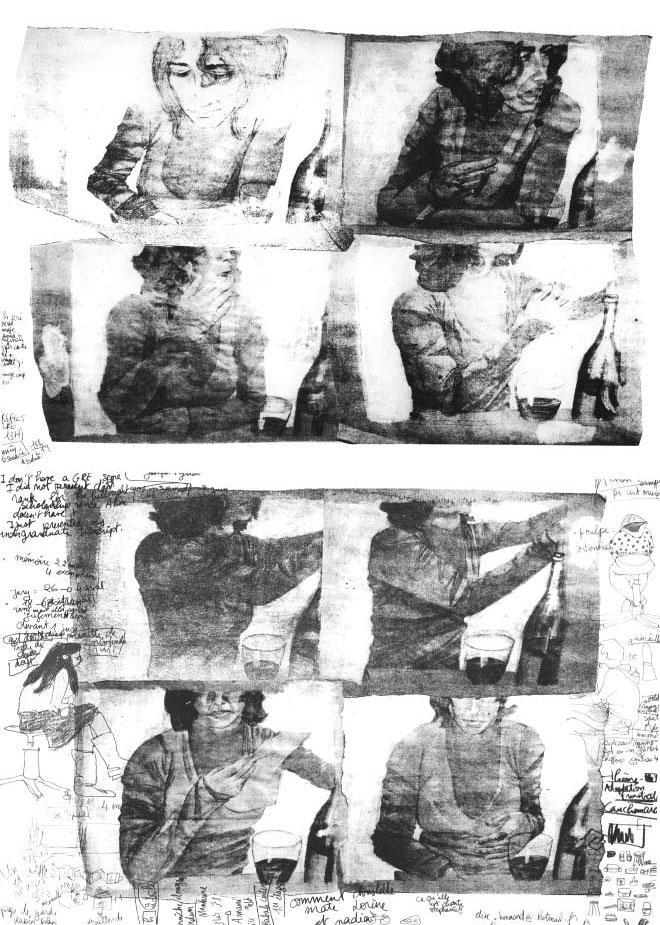

NA: Tell me a bit about your comic in Samandal, Lena. It’s about you and your mother, right? Does she read it?

LM: I read it to her. She’s losing her sight, so I’m trying to finish it at least so that she can see it, but it’s hard for her to read.

NA: And why is it called “Yogurt and Jam”?

LM: She eats yogurt with jam, and in Lebanon we eat it with cucumbers and salt. So I felt that this was a German way… the stories are real from my memory. Some of them are about us during the war, about her being a foreigner in Lebanon. My mom was born in Germany and met my father in Beirut when she was working here.

NA: You guys prepared a comic for Bidoun once that was a collaborative effort and dealt interestingly with sex, in the form of a hot flight hostess and also some of the horrors of puberty — like getting your period and stuff. How do you guys treat issues like sex in Samandal — as part of being young, as part of the scenery, or what?

FDZ: Well, I personally want more sex in the magazine. But we know that we’re going to get in trouble if we get any more explicit. We had a sex scene in Issue 2, and we had to keep discussing what will fly and what won’t — that was the first time we had to wonder whether we’d have to censor comics that we publish. But sex shouldn’t be a topic reserved for private screenings in art-house theaters.

NA: Do you guys have a policy about censorship? I mean beyond avoiding it?

FDZ: Well, now we do, which came out of that experience with Issue 2. We toyed with the idea of blacking out offending appendages. But found ourselves revolted with the notion. So we decided to go with it and then advise artists to not get explicit with penises and stuff.

HI: We’re lucky that a lot of stuff can go under the radar, since no one takes comics seriously.

FDZ: Ogdie submitted something for Issue 1 that was essentially one long sex-and-drugs scene. We’d love to publish that.

NA: And?

FDZ: But the consensus was that it’d probably land us in jail.

HATEM: Big time.

NA: Who is Samandal’s target audience, anyway?

HI: We don’t all agree. I think Omar dreams of having a much wider audience than we have now.

LM: This access and class thing is important to us. How do we get Samandal out? But it’s difficult. Still, I know people from the Palestinian camps who know it.

OMAR: It’s true, I want it to be as accessible as possible. I think everyone should read comics. They’re an amazingly efficient way to get information across. Comics have just as much potential to be insightful literary and visual masterpieces as they do mindless flashy entertainment, or just a combination of both. As for artists, the point is to popularize it enough here so that it can become a profession and not just a hobby.

NA: Did you ever think you would grow up and make comics?

OK: I wanted to become a paid comic book artist when I was fifteen. I think Fdz as well. But it was completely unrealistic, given the country we live in. It would be cool if someday soon a fifteen-year-old kid can aspire to get a paying gig at Samandal.

HI: I feel like we don’t have to worry too much about people reading it. If we make a good comic, people will come. My dentist has Issues 1 and 2.

NA: Besides your dentist, who reads it?

HI: Realistically, people from Beirut. People interested in visual arts.

FDZ: I’m not sure about that…

HI: Illustrators, graphic designers, filmmakers. Adults. Though we do have contributors and readers in high school, too.

FDZ: There’re people who pick it up because they used to do comics.

NA: I feel like you guys are somewhat at odds with the prevailing tendency of the art world here. Your experience of the war was via pop culture. You’re less precious about your experience of being Arab, being the product of war, being Lebanese…

HI: Being Lebanese is overrated. But with pop culture, sure. When our parents were watching the news, we were watching Jazeerat Al Kens. To me, that show is more about the war than all the documentary footage that we see on Al Jazeera today.

FDZ: I think what happens is that, naturally, the following generation deals with the products of war rather than the war itself. So being Lebanese is about speaking three languages — because everyone emigrated during the war. It’s about being obsessed with Japanese manga and anime because we relate to the battle against invaders and the missing fathers.

NA: How do you guys position yourselves in relation to the art scene?

HI: One foot inside the circle, the other outside. Sometimes I feel the circle is not interested in the work I do, particularly Samandal.

NA: It’s not serious or critical enough?

HI: Exactly.

NA: Who needs them?

HI: Well, we all do. They’ll come around. The whole world is taking comics more seriously. We also need time — I think in a few years, the material in the magazine will be so much better.

FDZ: I’m not too sure about that. I think the interest in the Arab world and comics is frivolous. It’s a fad. In a few years it’ll be GI Joe and China. But we need to milk it for what it’s worth.

HI: I disagree. Maybe Samandal will be a fad, but using comics to make art…

FDZ: Comics as art comes and goes.

HI: When did it come? The entire world is into comics now because a bunch of them are being turned into movies — Sin City, Batman, Daredevil, Superman…

HI: I think it’s the other way around. It’s the world is interested in these books that they are being turned into movies.

FDZ: Perhaps. But the same applies to the Arab world. The world’s ears perked up after 9/11. Soon it’ll be someone else.

NA: Okay, so who contributes to it, besides you? Who’s your youngest contributor?

FDZ: Hashem Raslan. He’s in high school. He sent us a comic about killing his teachers. I think he’s the youngest. Then there are the girls in Tripoli — they’re maybe nineteen.

NA: Who are the girls in Tripoli?

OK: They contacted us with a submission. They are very shy and quiet — three veiled girls who are influenced most by yaoi manga, which are Japanese comics about beautiful boys that fall in love with each other. It’s a genre. I found it very peculiar.

NA: Do they know Japanese?

OK: No, they were reading online fan translations, which have horrendous English. They even have Japanese nicknames for one another. The comics they wrote were oriented from right to left, like Japanese comics, and their writing was in English. The girls submitted tales of unrequited love!

NA: What is the most surprising response, whether fan mail or criticism, you’ve gotten?

FDZ: We’ve received an odd, quasi-fundie threat telling us that we have been warned and to expect sudden death at any time, from anywhere. It was probably spam mail, though.

NA: What about politics? You’re a comics magazine for adults in a particular region at a particular time. I’m thinking of Omar’s comic, “Salon Tarek El Khurafi.” In Issue 2, your protagonist is arrested for manufacturing “imaginary artifacts.” He’s encouraging escapist, individualistic thought in pretty subtle ways. Do you see Samandal as an alternative space for…

OK: Definitely. For me, Samandal was a way to do political commentary in a way we don’t see it in Lebanese literature or media. Because commentary here is always so direct and tends to offend people in such a charged climate. Whereas this is a bit like Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta.

LM: I think the best thing about Omar’s comic is his ease with the unknown, the imaginary. We rarely see comics or books that go into the fantastic and the magical.

NA: Is there a tradition of science fiction in the Arab world?

OMAR: There used to be a tradition of fantasy a long time ago, like 1001 Nights — that’s extremely rich. I wanted to revive that and modernize it. My themes touch on religion, and I guess that’s very closely related to imagination and the unknown for me.

NA: Who are your characters?

OK: I have three main characters. Sura, a second-year design student who is trying to express her imagination visually in a place that heavily censors it. There’s Lulwa — her and Sura grew up in the same village. She’s moving to the city for the first time and is forced to stay with Sura. And there’s Malek, a physics student whose family life was ruined by a religious party.

NA: Heavy. Do any of them stand in for you?

OK: All my characters are different facets of myself. But I’ve heard people say that the one that is most like me is Sura. Yesterday someone told me that they found it funny because she looks like my wife, wearing my glasses, but speaking like me.

NA: I like that, Omar in drag. Talk to me about “The Educator.” It’s very… evocative. It feels very Orwellian in ambition and tenor.

FDZ: Everyone loves “The Educator.”

HI: Not everyone.

FDZ: I think his art is quite striking. And when rifling through the magazine, it just leaps at you.

NA: And the girl is hot.

FDZ: The girl hangs in my bedroom.

NA: How so?

FDZ: A drawing. In a frame.

HI: Fouad Mezher, the creator, has managed to use the genre in a suitable way for Lebanon.

FDZ: “The Educator” is a subtle way of dealing with the situation. So is Omar’s comic.

HI: We totally need a crime-fighting vigilante.

FDZ: I don’t think we do. They’re all fucking vigilantes.

HI: But they don’t have cool costumes…

FDZ: Masks and costumes will only make them worse.

HI: I’m just saying, it makes sense for costumed heroes to appear in today’s Beirut.

FDZ: So Omar can liken the government to puppeteering automatons. Fouad can say that the institution is doping the people into submission. And I imagine we can get a lot nastier and specific and still get away with it. Ali Dirany deals with Lebanon in a very interesting way as well, in his comic. The main character lives in a constant state of psychosis, his eyes stare out vacantly, he walks around with a wrench through a psychedelic rendition of Beirut.

HI: I love how radical he is.

FDZ: And he deals with its best and worst with the same blasé numbness. I personally find Ali Dirany’s work, Misbah, more directly political.

HI: I agree. No allegories.

NA: I want to ask you guys about how you work. Where do you meet?

HATEM: In our homes.

NA: Which?

FDZ: Those that don’t have cats.

NA: You hate cats?

FDZ: No, Hatem is mortally allergic.

NA: So he’ll die?

HI: No, I’ll sneeze.

NA: What was the last big fight you had?

FDZ: We try to have them on a regular basis.

HI: It’s healthy.

FDZ: The makeup sex is good.

HI: What do you want to know? We’re not too keen on publishing our dirty laundry.

HI: I can say that the difficulty comes in part because of the crossing of friendship and work. That’s where things get messy.

NA: You and FDZ are BFF, right?

FDZ: Not forever.

HATEM: BFF?

FDZ: We do ten-year contracts. With the possibility of renewal.

HI: I gave you my heart.

FDZ: That was ten Christmases ago.

NA: But seriously, you met at AUB, right?

HI: Yes, we met at AUB. Fdz was the weirdest dude in class.

FDZ: What?

HI: And I was an absolute nerd. I was the loner. I had a cap on for a whole year. No one ever saw my hair.

FDZ: But we had different sides of the studio. Hatem was the unassuming gem in class. But too bad, he was surrounded by weirdoes.

HATEM: Fdz spoke of comics and radioheads and Star Wars.

FDZ: He sat next to Texas Boots.

HI: We used to call him Pifpaf. He was a pair of boots that grew appendages and stumbled into graphic design. He was known for his striking yellow turtleneck with black leather.

FDZ: And he had his phone in a hip holster.

HI: I would love to meet him again. He had the coolest rings.

FDZ: If we remembered his name, we’d show you his Facebook account.

NA: Is he, like, a venture capitalist now?

FDZ: Nah, he’s likely a shoe salesman.

HI: Or a dentist.

NA: Always with the dentist.

FDZ: Or a comics artist!

HI: Yes!

NA: Okay, we’re digressing. Last question, and it’s odd that I didn’t even think of this earlier. Why Samandal anyway, why this name?

HI: It’s “salamander” in Arabic. I guess it’s somewhere between picture and text. Like a salamander is between water and land.

NA: Salamanders are from fire, right? According to legend. And why is the subtitle Picture Stories?

HI: There’s no one word for comics in Arabic!

FDZ: But we’re kind of trying to change that.