In 1994, when the BBC’s legendary radio host John Peel traveled to Istanbul to explore the city’s modest underground music scene, he was immediately directed to Serhat Köksal, aka 2/5BZ. The Istanbul native performed live audiovisual collages — noisy collisions of kitschy Turkish melodramas and action movies, traditional songs and bleating Casiotones. “Of all the music I heard in Turkey,” Peel said on air after returning to London, where he began playing Köksal’s work regularly on his show, “I liked 2/5BZ best.”

Regardless of how much music Peel did in fact hear in Turkey, he wouldn’t have come across anything like 2/5BZ. The Istanbul scene’s most adventurous players were experimenting with metal and goth; as far as Köksal knew, he was working in a vacuum. “There was nobody else making music that drew on folk, pop, commercials, and improvised and electronic music,” he says. His influences were Stockhausen and Turkish psychedelic music, film soundtracks, comic books, and video games. Köksal dates his birth as an artist to 1982, when, at the age of fourteen, he produced what he describes as his “first finished work”: a cartoon on a notepad, called “Men Playing Ping Pong and Ajda Pekkan vs. Supertrashmen.”

Satellite television arrived in Turkey in the early 1990s, breaking the state’s stranglehold on information. Köksal remembers it as “a massive bombardment of popular culture.” He began to tape what he saw and integrate the clips into his performances; he skewered government-sponsored images of Turkey, juxtaposing them with clips from 16mm films that he recovered by haunting Istanbul’s flea markets. (Many of those films had seemingly become trash overnight, unwelcome reminders of an era that the military coup of 1980 had brought to an end.) The lo-fi collages he cobbled together from those disparate materials have since evolved into complex, even symphonic, audiovisual performances. There are breakbeats that fuse grime and dub with chintzy Oriental tunes and the occasional unadulterated Anatolian folk song; droning monologues are backed by the serpentine whine of ancient horns, which are interrupted by news reports, speeches, and opera snippets. The gritty palimpsests call to mind the archival resurrections of Boyd Rice / NON, the manic plunderphonics of Negativland, the enthused appropriations of the Sun City Girls, and the cut-ups of William S. Burroughs. For all this, they’re not aesthetic exercises so much as harrowing postcards from Turkey’s experience of globalization, real and imagined.

So there was a certain irony to Köksal’s emergence onto the international art-music scene radar by way of the BBC. Peel, of course, was a genuine supporter, and a connoisseur of music he found to be compelling, challenging, and novel. That included music from home or abroad that flashed the bird at the Queen. And yet the titles of Köksal’s compositions and performances are relentless in their critique of commodified world-music culture: “No Cultural Pipeline No Energy Dialogue”; “No Turistik No Egzotik”; “No Gasionalism No Pipeline Bridge No Goethe No Hafez No Biennial”; “No Ethnic Market No Exotic.” (Of course, it was an insight of punk that negation could be good for business.)

Köksal’s work has long been characterized by what it rejects: global biennials that turn artists and their work into emblems of the exotic; the promotion of tourism that does the same to a country’s citizens; the establishment of economic bonds between nations by and for their elites, under the guise of what he calls “dialogue fetishism.” Beğenal, a program of concerts, video screenings, performances, and political theatrics shadowing this year’s Istanbul Biennial, which ran through November 8, is the latest project to take up these criticisms. Pronounced almost like “biennial,” beğenal is Turkish for “if you like it, buy it”; the project’s logo is a man-as-red-star caricature vomiting up various corporate-style logos, responding to the biennial’s slogan — courtesy of Brecht: “What Keeps Mankind Alive?” — with “This Is How Mankind Pukes!” Köksal’s sardonic parroting of corporate artspeak stems from “the shared approaches of national ministries of economic affairs, global corporations, and major cultural programs, which all use the same standard, artificial language — everything is a ‘dialogue’ or a ‘bridge’ — whether to brand a city or a product or an artist, all in service of the integration of the international economic system.”

But Köksal is no mere refusenik. For the last year, he has been spearheading the International Roaming Biennial of Tehran, a nomadic exhibition of work that has traveled to Berlin, Istanbul, and Belgrade and will soon alight in Beirut. The biennial’s inaugural theme is Urban Jealousy. During a trip to Tehran in 2001, while he was working on the soundtrack to a documentary called Tehran 1930, he met a number of artists whose work he liked. He entertained the idea of showing their work in Istanbul, but thought it would be too much “like all the other exhibitions of Istanbul artists held in Europe, which have some terrible theme, and some of the artists are flown in to attend.” On a later visit, though, he heard some artists joking about how lucky they were not to have a biennial in the country. At which point Köksal and his Iranian co-curator Amirali Ghasemi decided to give them one. In Köksal’s typically tongue-in-cheek style of presentation, the biennial is also described as an effort to bring Iranian artists to the market so that they can get “a chance to share the profits” made at art fairs and auctions held annually in Sharjah, Dubai, and Istanbul — traveling like nomads will only make them more appealing to buyers looking for a rare prize.

Köksal attributes his satirical bent to the influence of Aziz Nesin. The infamous Turkish writer and activist, who once called his country “a capitalist scrap pile,” was a perennial thorn in the side of the state and turned lampooning the bureaucracy into a heroic act. Nesin’s pairing of humor and vitriol is evident in a series of new films Köksal called “gentrifisuals”: TV advertisements for cities where gentrification is occurring, sun-kissed scenes of the bourgeoisie at play among the remnants of history. So far, he has produced ads for Istanbul, Berlin, and Belgrade, all of which play on the branding of cities as hubs of the so-called creative class, empty vessels (or lofts) ready to be filled with new money and aesthetic pleasures. As with his mock-biennials, artists and other creative types are used to develop an appealing image of the city for potential visitors and investors. “I don’t take these expositions of culture seriously,” Köksal says, “because they’re mostly there to serve the stewards of the global economy. They exist only as decoration or window dressing.”

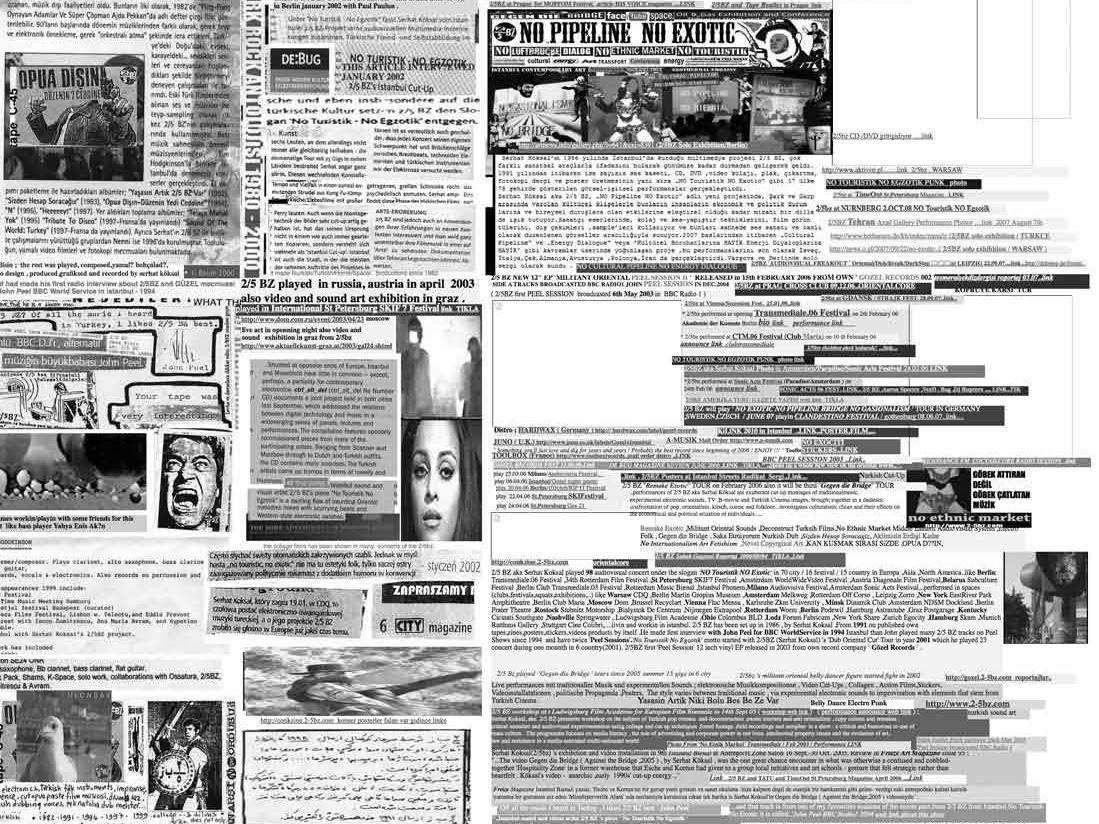

As an antidote to that system, Köksal set up his own record label, Gozel, a one-man multimedia production house that puts out CDs and DVDs, zines, stickers, posters, tapes, and vinyl. But his aesthetic, and all it represents, is perhaps best embodied by the 2/5BZ website, a massive tangle of information that looks like a primitive MySpace page plastered over a Bulletin Board System laced with punk flyers. There is a word for it, a gelatinous byproduct of industrial production that has come to signify the lowest common denominator of the technologized global economy: spam. Köksal’s site hosts a nearly indecipherable mess of images, Technicolor columns of text, film clips, posters, articles, stray phrases (Orientalcore, DECONSTRUCTING TURKISH FILMS & REMAKE, Belly Dance Electro Punk), and links to his seemingly endless stream of projects — a thousand bits of information bleeding in colloidal suspension.