Bamako

Sixth African Photography Encounters: Another World

Maison Africaine de la Photographie

November 10–December 10, 2005

Over the past twelve years, Mali’s biennial ‘African Photography Encounters’ has become a key fixture on the global photography calendar. Since taking over in 2001, curator Simon Njami has brought in diasporic and other international photographers to show in Bamako and multiplied the number of sidebar exhibitions; this year, the biennial included work from approximately sixty countries. In addition to master classes in Mali, workshops are now held in Burkina Faso, Congo and Gabon. Njami seems aware of the potential pitfalls of the “international exhibition” held outside of what is typically assumed to be the “international world,” and maintains that the festival must first and foremost be “anchored to Bamako.” ‘Another World’ aimed to confirm the status of the city as the capital of African photography and the event as a survey that crosses both geographical and artistic boundaries.

In the 2003 biennial, ‘Sacred Rites, Profane Rites,’ several notable female photographers, in particular Gabon artist Myriam Mihindou, attained international recognition. Mihindou’s 2003 series The Relic for a Domestic Body was a moving collection of images of sculptural icons that explored the particular tension that precedes violence. Nigerian Fatimah Tuggar, who received the 2003 Jury Prize for her digitalized pastiches of postcolonial Africa, here exhibited a video, Fusion Cuisine (2000), in which she pursued her “critical meditation on the reproducibility and the effects of globalization.” Together with Jane Alexander, Lien Botha, Malala Andrialavidrazana, Fatima Mazmouz and Sarah Sadki, Mihindou and Tuggar mark the emergence of a generation of female contemporary photographers from the continent. The international prize was awarded to Rana El Nemr, an Egyptian born in Germany in 1974; her images of women on the Cairo subway is a subtle study of über-urbanization.

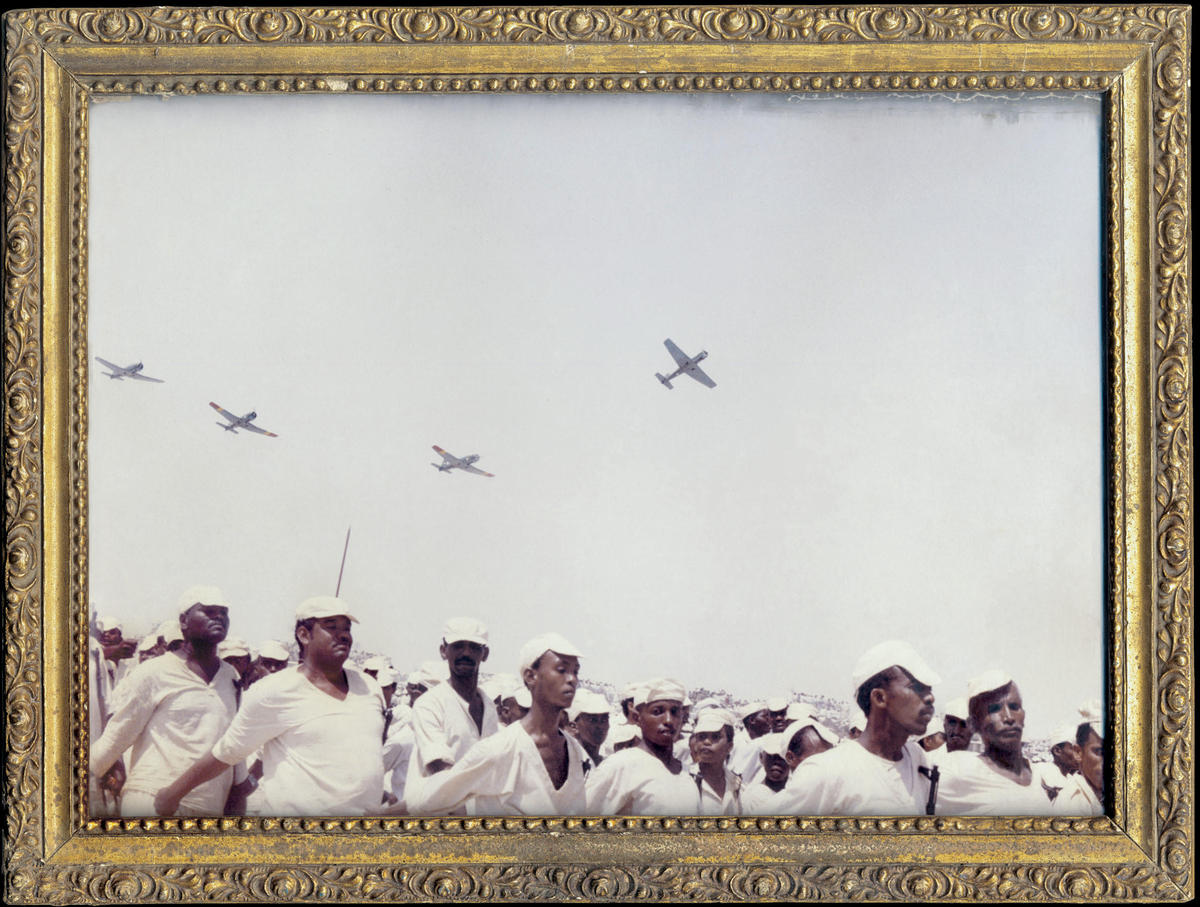

The biennial also attempts to trace the photography of a “forgotten country,” which this year was Sudan. Images by a range of photographers, dating from 1935 to 2002, were about heritage, rather than testimony and aesthetics, and included private city and bush studios, documentary images, and art and society photography. In its sixth year, Bamako also sought to confirm its statusasthehome of African photojournalism, highlighting in particular work by South African Guy Tillim. In a more complete survey of his oeuvre than the solo show at Madrid’s Photo España in June 2005, the biennial included his documentation of Johannesburg’s inner city transformation from white enclave to a genuine “African city.” Tillim’s taut framing and remarkable use of color take his images out of the field of reportage and into that of visual art.

Among the continent’s younger practitioners, Nigerian photographic collective DOF (Depth of Field) stands out. Emeka Okereke won the African Prize at Bamako in 2003; the 2005 biennial included dramatic color images by two other DOF members, Zaynab Toyosi Odunsi and Uchechukwu James Iroha (who had already received the French Development Agency’s Elan prize for his coverage of the blood bath that is a Lagos abattoir. Among a strong selection of work from Algeria, curated by Michket Krifa, was some outstanding work by another up and coming photojournalist, Zohra Bensemra, who works for Reuters in Algiers. Her images map events in Algeria through the “hell decade” of the 1990s, including the Ain Temounchet earthquake and Kabyle demonstrations, and the local elections boycott in 2002. In a more understated but equally potent series, Nadia Ferroukhi drew parallels between Algeria’s murky, trash-filled street corners and the fate of women abandoned in social centers.

The Bamako festival highlights the diversity of African photography — once seen as the domain of the portraitist à la Seydou Keita — and the gradual acceptance of African photographers as artists. The process comes with its own irony. Take the buoyant Bamako studio photographer Mamadou Konaté, winner of the African AccorTalent prize, who has abandoned his studio practice “to crop the heads of people [in his images]” in order to “make contemporary art.” The art market for images of Africa-throughthe-eyes-of-Africans may be nonexistent in Africa, but it’s beginning to show signs of awakening, thanks in part to Bamako’s ‘Another World.’