Sophia: For starters, Jean is a lesbian.

Dorothy: Ma.

Blanche: What’s funny about that?

Sophia: You aren’t surprised?

Blanche: Of course not. I mean I’ve never known any personally, but isn’t Danny Thomas one?

Dorothy: Not Lebanese, Blanche. Lesbian.

— Golden Girls, “Isn’t It Romantic?”

My cousin Hadoi Ka’awit is five years old. He still likes to cuddle with his three older sisters and mother Fatima. He’s got legs and arms as skinny as a goat and long lashes that fringe his big eyes. He’s sweet and sensitive and likes to pad at my hair with a brush and sponge at my face with cakey makeup and chatter about his two favorite things: the mantis-faced Bratz dolls that belong to his sisters and Freej, the blockbuster Emirati cartoon sitcom about four old biddies in Dubai.

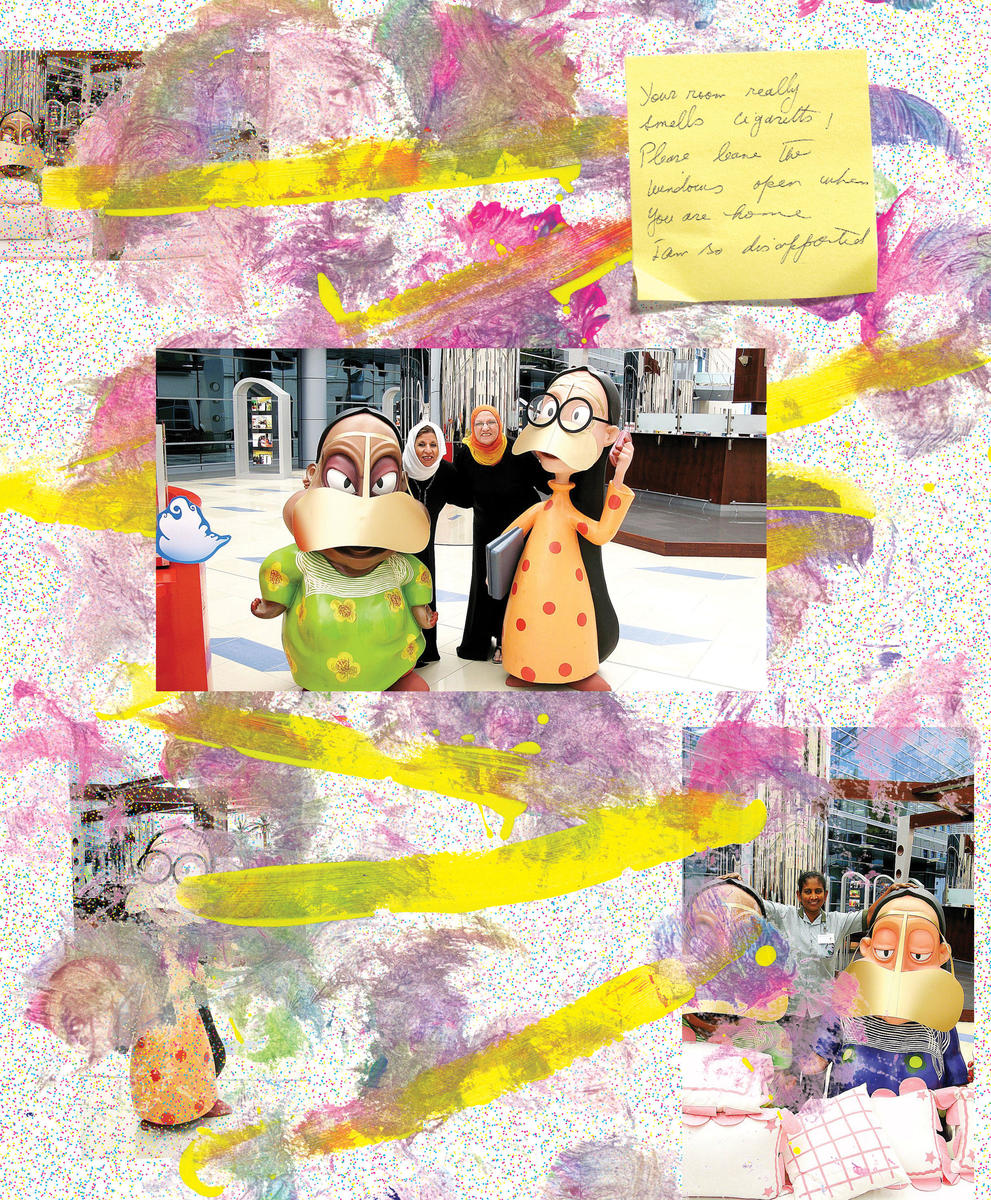

Since its debut in the coveted iftar primetime slot in 2006, Freej has emblazoned the diva-like Um Khammas, sporty Um Saeed, tech-savvy Um Allawi, and ditzy Um Saloom onto the hearts and minds of people across the region. Freej means “neighborhood” in Gulfi Arabic, and the Ums chill together at Um Saeed’s place. Um Saeed’s little mud-and-straw house is center stage for the show, a dusty sanctuary where the four merry widows banish their dead husbands from their lives, hatch schemes for fame and riches, plan vacations and retreats, and are completely free from the constraints of Gulf society, notwithstanding occasional visits from children and grandchildren.

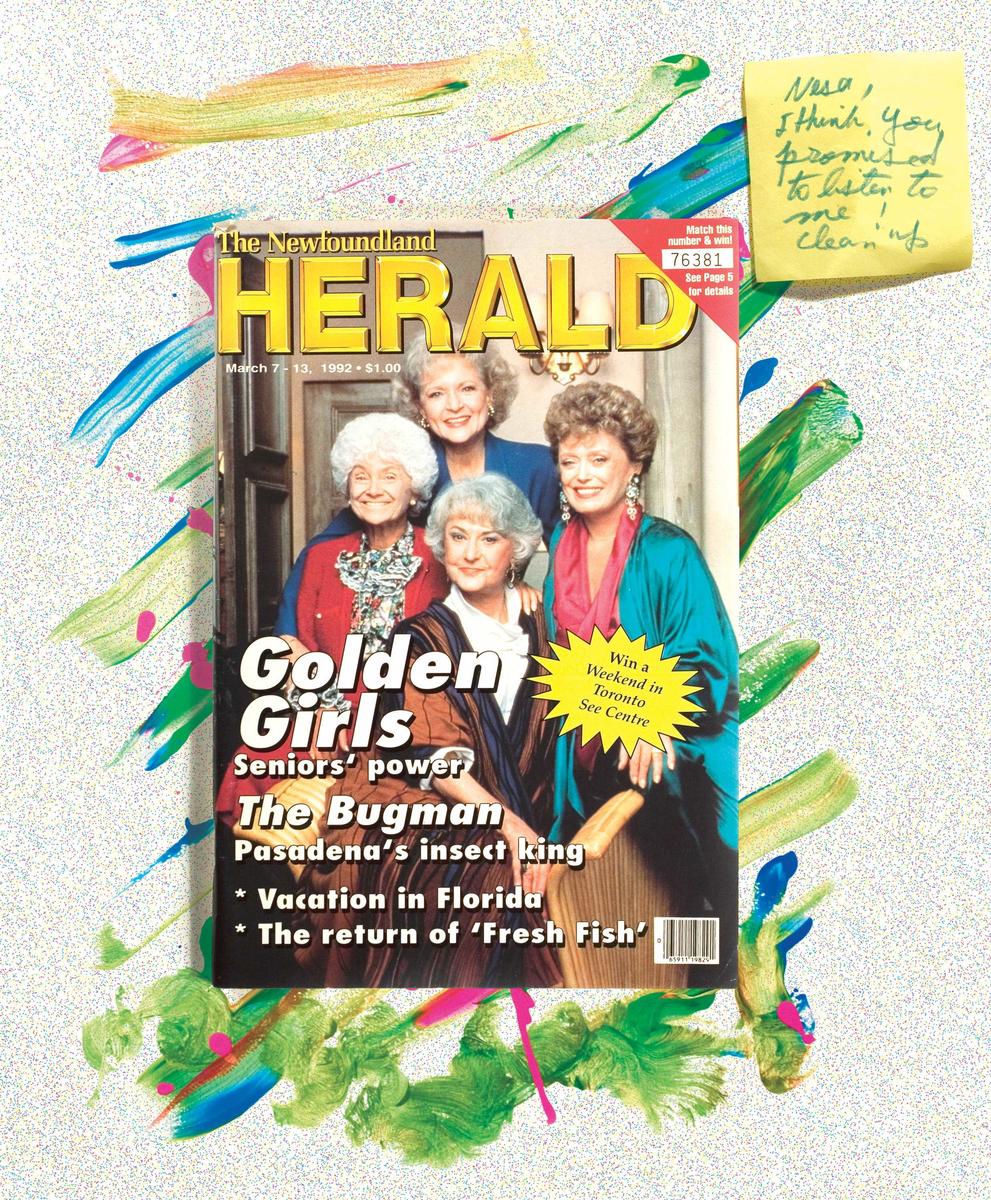

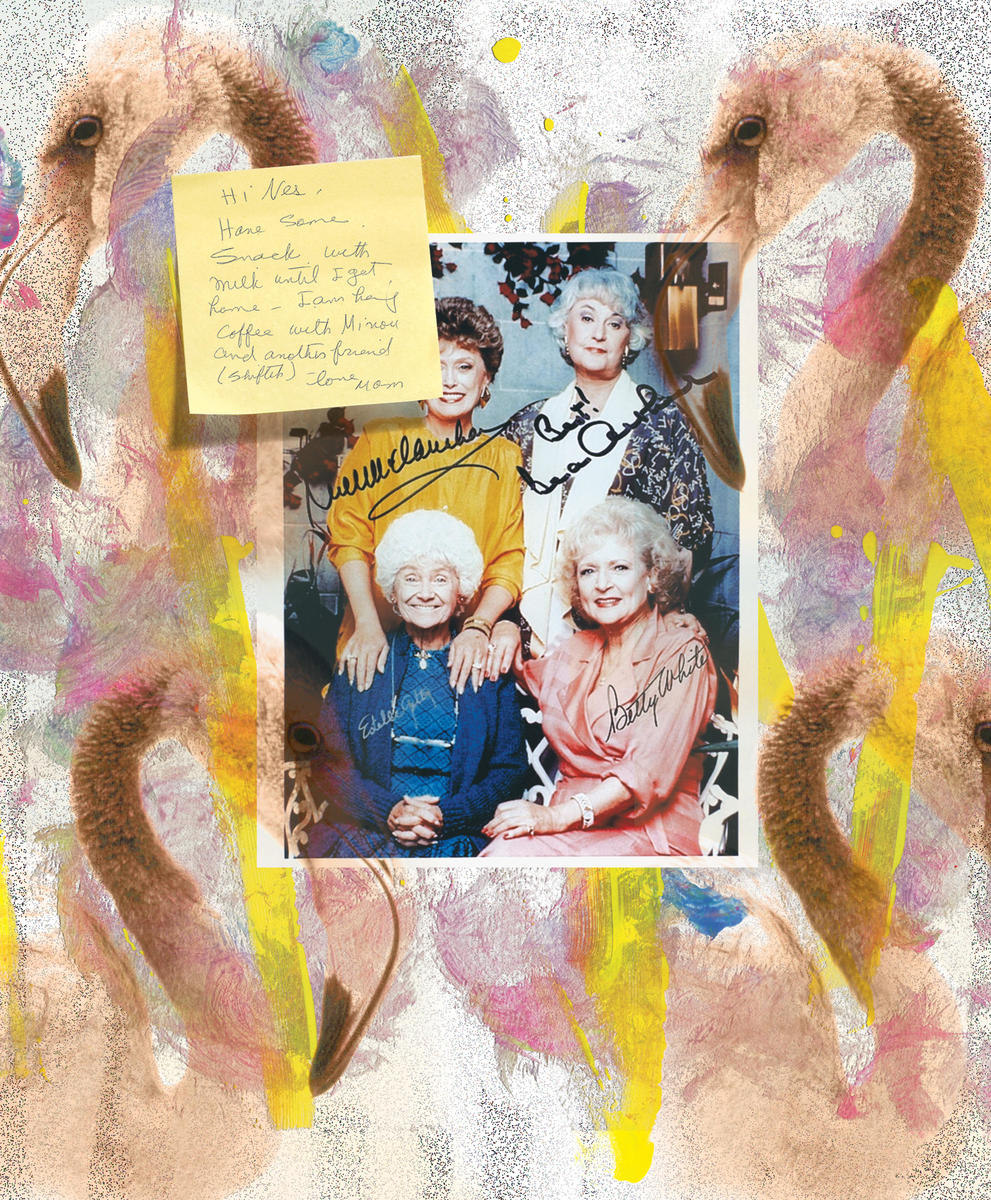

If this constellation seems a lot like a certain American situation comedy about four aged women bantering and bonding over coffee and cheesecake at an old friend’s house, it’s because Freej was directly inspired by The Golden Girls. (Mohammed Saeed Harib, the show’s creator said so in an interview.)

At times it can seem as though the primordial archetypes of Rose, Blanche, Dorothy, and Sophia have been dressed up in polka-dot djellaba and let loose upon the Gulf. Jokes, morals, situations, and set pieces are freely borrowed; even the thatch-and-carpet décor at Um Saeed’s house seems like a muted echo of Blanche’s wicker-laden home in the heart of Florida’s retirement community. When the Ums attempt to impose a “cultural makeover” on their neighbor’s yoga-posing, English-chattering “bohemian teenage daughter,” I immediately remembered the full-court press the Golden Girls delivered to Blanche’s slutty niece when she came down to visit them in Miami. Freej is full of witty jabs at crusty Khaleeji society, too, and it has made a name for itself with its frank airing of taboo topics, including religion, death, and plastic surgery. In the episode “False Alarm,” Um Khammas’s doctor gives her just ten days to live, and she goes on a religious bender, spreading goodwill and doing good deeds. It’s a great episode that seems to pay homage to the classic Golden Girls episode “72 Hours,” in which a close call with HIV leads Rose to completely change her life (for a few days). Of course, some “issues” are not, as it were, translatable. One very special Freej treats demonic possession, as our ladies witness a series of exorcisms, including that of a snooty British jinn named Michael who wants to go on safari and an Egyptian jinn named Fatakat who just wants to ride in a Land Cruiser.

The cast of characters on Freej is extensive. There is Abdullah Bil Khair, a traditional singer with a Saddam mustache and a penchant for colorful sashes and ruby-red beads. Um Khammas’s terrifying and blind mother Um Khammas often drops by for a jab at the girls. And then there are the hangdog faces of the various Filipina and Indian maids, salesmen, and drivers. The good-natured racial “satire” on the show is one of the less attractive elements of Freej, but it’s also one of the funniest. Think of the classic Golden Girls gag in which Sophia mistakes Blanche in a mud mask for a black man or spews, apropos of nothing, “I’m an old white woman. I’m not supposed to have color. You want color? Talk to Lena Horne.” It’s possible that we wouldn’t allow ourselves to enjoy these not-so-elaborate jokes if the protagonists were younger. But the crone occupies a unique place in comedy as the insulting and cruel truth-sayer. We have to pardon her with a chuckle, however serrated her stories and aphorisms.

Jason: Isn’t she the most beautiful mother you have ever seen?

Sophia: Grand, just grand.

—The Golden Girls, “Even Grandmas Get the Blues”

In 1992, when The Golden Girls went off-air, I was nine years old and living the dream in Puyallup, Washington. I had a beautiful grandmother who wore Hush Puppy high heels, baked yellow cake with chocolate frosting once a week, and had a fluffy white permanent just like Rose Nylund’s. It’s a mystery why every kid’s favorite Golden Girl is Rose, but for my part I always confused Betty White with my grandmother. I was confused about a lot of things, including the mechanics of sex, which I had begun to speculate about in my diary. I drew pictures of body parts in code — ice creams topped with cherries that were actually boobs, a woman in a short skirt with labia that hung down so low that I put shoes on them to make it look like an innocent picture of a woman with four legs. Having never seen a penis in our family of women (Grandpa was dead; my aunts were both divorced; my cousins, all single white females; my father, in Abu Dhabi; my sibling, a girl), I drew boys from school with twigs and lightning bolts on their crotches. I tried out words like dildo and humping in cursive. When my mother found the diary, she was horrified and made me rip every page out and into little pieces while sitting in the closet of her bedroom, facing the wall. She said it was a lesson learned, for both of us, but it left me with a sense of shame and fear of writing that took many years to overcome. The only person who kept calm throughout the diary ordeal was Grandma. She took me under the soft folds of her arm-waddle and squeezed me into the rocking chair. It was as satisfying and comforting as a “lesson learned” at the end of a Golden Girls episode about forgiveness and understanding. I curled against her round hip and sucked in Alf and The Cosby Show. I lived under Grandma’s protection for a week, staying up every night to watch TV while my mother sat in the kitchen weeping on the phone to my faraway father about my disgusting diary.

Someone recently observed that Rose is the most deceptive of the GG crew. She blithely tags along on adventures, revealing with perfect comedic timing that those dainty hands castrated bulls back in St. Olaf, or that she’s killed multiple partners with her bare sex. I don’t know about the sex part, but in other ways my grandmother really was like Rose. Later in life I found out how the gentle grandmother who treated our scraped knees with severed aloe vera stalks and cold-creamed her face every night had started working in a cannery at fourteen; how at thirty she owned a successful Tacoma tavern; how in her forties she took a bullet in her belly, the tiny scar highlighted by the pink band left by her cinched apron; or how at sixty she survived breast cancer and went blind but continued to run a five-acre raspberry farm and raise two Arab granddaughters from her stable of all-blonde, all-female offspring. She never retired to sunny Florida or gave up running a farm for a manageable allotment in the neighboring Golden Rose trailer park, where many of the townsfolk Grandma had been around her entire life had ended up.

The Golden Rose sprawled on the other side of the squash patch where our property line petered off. It was a sherbet-colored, pink-flamingoed, Kiwanis-spawning fantasyland for pensioners who couldn’t make it to sunnier climes. Our closest neighbor was Gladys. Her trailer was covered in sea-foam aluminum siding, and her small patch of dusty miller and fern was crammed with garden ornaments, cast-iron bucks, and a wooden cutout painted to look like an old woman bending over to reveal polka-dot underwear. Her garden straggled into the gravel path leading up to ours, and she made the trip between houses at least twice a week, sometimes to tighten Grandma’s do and stink up the house with perm solution and other times just to chatter over pie and coffee about her dead husband, her deadbeat sons, and the vulture-like surveyors who’d been hanging around, eyeing the property for development. Gladys was beautiful, but not like my grandmother. Grandma wore seersucker dresses and no perfume and pickled horseradish for fun; Gladys sported slick pantsuits, dyed her hair black, wore orange lipstick, and smoked a pack a day. At the end of Gladys’s visits she would always stub out her cigarette, lift an eyebrow, and point a hooked acrylic fingernail at Grandma, saying, “So stick that in yer pipe and smoke it,” before ducking out the back door with her Pomeranian, Tootsie.

I idolized Gladys and the other, less frequent lady callers from the Golden Rose and spent a good chunk of time after school with the TV on mute so I could eavesdrop on their conversations. And hanging almost exclusively around old ladies had an effect on my sensibilities. I felt more comfortable clipping my grandmother’s toenails in front of the five o’clock news than I ever did going to Kalles Junior High’s Winter Tolo. Every Sunday, well into seventh grade, I copied and memorized dance numbers off the Lawrence Welk Show, wearing velour tracksuits at a time when velour tracksuits were reserved for eighty-somethings. For a long time, I existed in a kind of dejected in-between place, with few friends my age and the sensibilities, sarcastic and sartorial, of an old lady. Friends of mine today sometimes say that I am a gay man trapped in the body of woman. I am not entirely sure what that means, or how to think about it. Mostly I’m flattered. But whatever they’re seeing in me is undoubtedly yet another legacy of my childhood among the golden girls of the Golden Rose and my redoubtable grandma, Grace.

Blanche: I don’t really mind Clayton being homosexual, I just don’t like him dating men.

Dorothy: You really haven’t grasped the concept of this gay thing yet, have you?

Blanche: There must be homosexuals who date women.

Sophia: Yeah, they’re called lesbians.

—The Golden Girls, “Sisters of the Bride”

My cousin Fatima is worried about Hadoi. Worried doesn’t quite describe it — she has an almost hysterical fear that his favorite TV show is turning her son into a homosexual. Hadoi hoards advertisements and flyers and coloring book pages that have to do with Freej, carrying them around in a makeshift junior version of a man-purse (which is actually a purple canvas lunch bag with a Velcro lip). Fatima frequently finds Hadoi hidden under the stairwell or bed, having abducted one of his sister’s dolls, singing to himself and snapping the sculpted plastic feet on and off Jade’s peg legs. Hadoi is gentle when he chatters to his plastic female friends, engaging in elaborate conversations about clip-in hair extensions and the glitter accessories he’s scavenged from under the beds and cupboards in his sisters’ room. He talks to me the same way while braiding my hair.

Fatima doesn’t want Hadoi picking up the swift backtalk or funny walk of his favorite, Um Khammas. So she encourages him to take after my least favorite character on the show, Um Khammas’s grandson, Abood. The boy is a kind of Bart Simpson or Dennis the Menace type, except meaner: he steals money, disrespects his elders, tortures animals, and generally acts out, in the mode of countless spoiled boy-children across the Gulf. Fatima dresses Hadoi in Abood pajamas, showers him with Abood paraphernalia, and even bought him a bottle of watermelon-scented Abood cologne. I don’t understand what my cousin is thinking, just as I can’t figure out for the life of me why this amazing, charming, subversive show makes such a fuss over this loathsome tyke. My cousin Afrah insists it’s just the pleasure of recognition: “We all know somebody like Abood.” Unfortunately, this is true. In Doha, in my father’s extended family, that somebody is my cousin Azooz.

Like Abood, Azooz is mischievous and cute. Like Abood, Azooz drives me kind of crazy. I think it’s the animals. Like Abood — and like Jeffrey Dahmer — Azooz likes to kill things. During one of our camping trips, he bashed a newborn goat on the head with a rock. We found the brained kid next to a sack of feed, its twiggy little legs curled up under it and its body surprisingly small.

One night I caught Azooz jabbing the butt of a toy bunduqiya (spinning rifle) at his sister and Nora Ka’awit, who were cowering in the toilet. I grabbed him by the nape of his thobe and dragged him into the hall. He was scared and struggling before I even went at him in English. The girls scampered off silently, just as frightened by my outburst as they’d been by Azooz’s violence. His mother, Zayna, came storming in at the sound of her baby’s wail. She picked him up with one swift sweep and told me off like I probably deserved.

“It’s okay if I yell at him, but you! You’re just his cousin! And you’re strange to him, and he’s frightened when you talk in Engleesi!”

“Good. You should have seen how he scared the girls.”

“No, they like playing like that.”

“What are they playing — war crime?!”

The hardest part for me is that Fatima wishes her own and only son would be more like Azooz. Naturally, Azooz torments Hadoi.

The worst was a wedding night — I don’t remember whose. The Ka’awit brood had gathered to watch their mother get ready, powdering and primping at her vanity mirror. Azooz stood in front of Fatima, adjusting his tiny sunglasses and wrapping his Emirati-style hamdania at various jaunty angles. Hadoi came veering into the room, his voice a high-pitched whine, his eldest sister in hot pursuit.

“Uma! Saweeli!” he begged, tugging at his mother’s satin dress with one spindly arm and wobbling beneath a huge bottle of Curious by Britney Spears, thrust up on the other arm like a glass shot put. The contrast of Azooz’s miniature masculinity and Hadoi’s ridiculous cries to be “done up” with perfume were funny until Fatima’s hennaed hand snatched the sloshing bottle away from him. “No, that’s for girls. I gave you boy’s perfume. I’ll put that on for you.”

Azooz pounced on Hadoi’s weakness, pushing him hard and giving him that signature double-middle finger-bang move so totally inappropriate for a kid his age. Azooz skipped out of the room yelling “Khwani!” at the top of his rotten little lungs. Hadoi was crying then, wailing and lunging up at the bottle of Curious, just out of his reach on the mini-fridge where my other grandmother kept her insulin. Fatima ripped open the Velcro on Hadoi’s lunch-bag purse to find a nest of Bratz paper scraps, the plastic bottle of Abood little-boy-body-spray missing.

“Where is it?” Fatima shrieked, gesturing fast and sharp with her arms to frighten Hadoi into a confession.

Then, suddenly, she collapsed onto the carpet in a heap of pleated taffeta and cheap, clangy jewelry. Her daughters, flounced to the nines in tulle, and her only son grudgingly wearing a “dancing” thobe with sleeves dangling to the floor, clustered around her.

“Get out!” she bellowed. My aunt Sarah and I ushered the kids out to the Nissan and went on ahead to the wedding. Of course, while the other boys flitted back and forth between tents, Hadoi stayed in the women’s tent with us, munching on seeds and silently watching the old women in coppery batoolas sing and beat their drums, occasionally pointing at the fattest and most formidable singer and saying, “Shoofi, Um Khammas!” For him, seeing a rotund wedding singer in a green djellaba was the same as spotting Minnie Mouse at Disneyland.

I feel bad for my cousin. Fatima missed the wedding, broken down over a missing bottle of watermelon-scented spritz. Anyone could see that the Abood merch, the bicycle, and the days-out-with-daddy intended to bait her son into hetero pursuits were doomed to failure. If Fatima had been ever seen The Golden Girls, she’d realize she just has to learn to love him for who he is. Blanche was a raging homophobe, too, but she managed to love her brother anyway.