ISTANBUL FILM FESTIVAL

The annual Istanbul Film Festival, now in its twenty-fourth year, gives cinema-goers the chance to see a selection of noteworthy international films as well as classic movies. In the absence of any alternative cinema, the festival functions as something of a cinematheque for the city. Most screenings take place in the lively Beyoglu/Istiklal Street area, which gives the festival the feeling of a local event — despite the sheer volume of films (about 200 this year) and presence of international stars such as Harvey Keitel, Jane Campion and Neil Jordan. This year, Istanbul’s increasing popularity was reflected in the number of foreign reporters attending the festival, who were ostensibly there to take in a dose of Turkish cinema.

Their favorite, and the winner of the National Competition, was Istanbul Tales (Anlat Istanbul). A collection of five stories by five different directors, the film was a little romantic for local critics, although it did ably portray the chaotic nature of the city. Actorturned-director Ugur Yucel’s Dogme-influenced Toss Up (Yazi Tura) proved more of a local hit: A portrait of two disillusioned men returning from military service in southeast Turkey, where they’d battled with the PKK, the film took the Best Director prize. Meanwhile, Semih Kaplanoglu’s second feature Angel’s Fall (Melegin Dususu), the story of a young, withdrawn, working-class girl who lives with her father, deservedly won the FIPRESCI award. Built around characters rather than twists and turns of the narrative, the film was influenced by the minimal style of Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-Liang, Kaplanoglu told Bidoun. And while it went unrewarded, Erden Kıral’s Yolda was a noteworthy exploration of the making of a legendary film, the late Yılmaz Güney’s Yol, which won the Palme d’Or in 1982 and was banned in Turkey for sixteen years. Güney, in jail during the making of the film, originally asked Kiral to direct on his behalf, but later changed his mind, opting for Gören instead. In a tribute to the Kurdish filmmaker, and to come to terms with his own past, Kiral created a fictional memoir of the production.

Overall, this was a mediocre year for Turkish cinema. As Istanbul strives to become a European cultural center as well as an increasingly popular tourist destination, a lot rests on the city’s artists and filmmakers: This critic, for one, hopes that the many upcoming artistic events prompt more innovative explorations of local culture.

CANNES FILM FESTIVAL

It takes a while for the film world to go through the motions. Besides puffed-up Hollywood cash cows (Shrek II, Troy), Cannes 2004 was dominated by the scatter-gun, left-lite fury of Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11. By 2005, the festival had turned to a coterie of old-school European auteurs and American indies and their more subtle analyses of the struggling individual in today’s unpredictable world. Critics who fancy themselves as mass psychoanalysts naturally put this down to the post-Iraq War effect; the Guardian’s Mark Lawson, for instance, drew a Venn diagram of the competition films’ alienation and guilt-ridden angst, of “characters with bombs hidden in their biography.”

Okay, critical favorites David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence and Michael Haneke’s Hidden both feature middle-class professionals suddenly threatened by strangers; Jim Jarmusch’s cute Broken Flowers and Wim Wenders’s Don’t Come Knocking deal with the discovery of children fathered in the past; and the Dardenne brothers’ Palme d’Or-winning The Child with fatherhood itself — but it’s easy to stretch the analogy. After all, the only film directly concerned with today’s fear-driven political environment was British documentary The Power of Nightmares, a provocative, sharp analysis of politicians’ distortion of the “terror” threat.

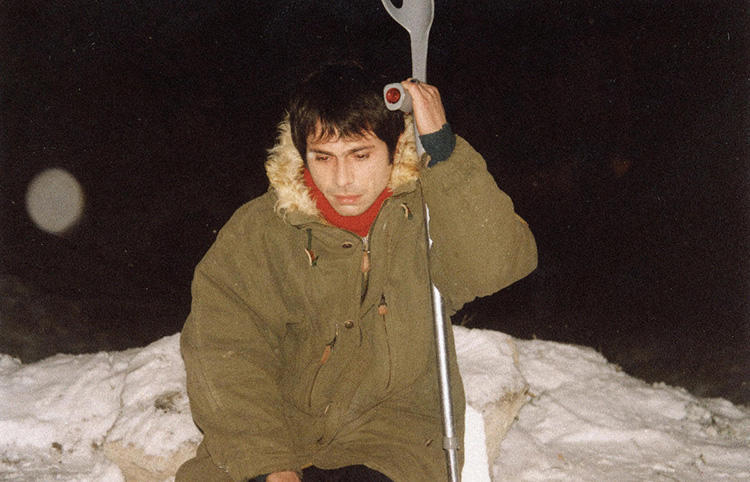

And was all this angst simply a tidy analysis for US-focused critics and an easy a hook for directors, if they really were inspired by such fears? Hiner Saleem, whose previous offering Vodka Lemon was a deft piece of surreal cinema, is one of few Middle Eastern directors to have tackled the Iraq war head-on. Kilometre Zero, hyped as the first Iraqi film to play in competition at Cannes, opens with an exiled Kurdish couple listening to a news report of the invasion which quotes an Iraqi — ostensibly the voice of the director — saying that they would have “welcomed liberation by France, Switzerland, Slovakia, but no one else came,” and ends with the couple shouting “We are free!” as the regime topples. In between these Paris-based bookends, the film flashes back to their life in Iraq in 1988 and Ako’s conscription to the Iran-Iraq war. As he is chosen to escort a fellow soldier’s corpse from Basra to Kurdistan, the film becomes something of a road movie, pitting a racist Arab driver against the Kurdish dreamer.

There were signs of the director’s quirky visual brilliance: Ako, ordered to keep out of sight in daylight, stumbles across car parks full of identical taxis with coffins on the roof, and a giant statue of Saddam on the back of a truck regularly criss-crosses the desert. But Saleem seems to stumble over his own emotions, resulting in a meandering storyline and stilted script. (He said that having rushed to Kurdistan after the war, the screenplay ended up being developed alongside the shoot.) Despite his somewhat disingenuous line that the film was not really political, prickly European journalists predictably took issue with his pro-war stance. It was a shame that proceedings were dominated by the usual predicament of the Middle Eastern filmmaker — never actually getting to discuss their films amid the politics — as Saleem had some winning stories about reconstructing the Saddam era in post-war Kurdistan, including having to bail his sculptor, mistaken for a Saddam enthusiast, out of jail.

Sadly, Masahiro Kobayashi’s Bashing, an exploration of how Japanese hostages in Iraq were shunned upon their return home, felt like another slightly wasted opportunity. Despite a fascinating premise, the film, based on true events, was relentless in its approach and took place entirely on the surface. The lack of background — even Iraq is assumed, as the location is never mentioned — impeded understanding of why the former hostages suffered such abuse.

Two competing films from established Israeli directors attempted a new perspective, with varying results. Avi Mograbi’s Avenge But One of My Two Eyes is a low-tech documentary structured around phone calls between the director and a despairing Palestinian friend. Their conversation is interspersed with footage of young American tourists learning about the myth of Masada, Palestinians suffering humiliation in their fields and at checkpoints, and an Israeli concert by right-wing veteran Kahana at which fundamentalists call for “revenge” on Palestine. Mograbi’s film, while hardly groundbreaking, includes some shocking footage and adds to the body of work by Palestinian documentary directors.

The selection of Amos Gitai’s Free Zone, however, seemed to defy all critical judgment. The first Israel-Jordan co-production on record, the film begins with a draining ten-minute close-up of Natalie Portman’s American character grieving over a break-up with her Israeli fiancee, but then descends into an unrealistic road trip across the border to Jordan’s industrial free zone. Ostensibly a tale of three women — Portman, Hanna Laslo as an Israeli taxi driver, and Hiam Abbass as a Jordanian-Palestinian businesswoman — the film boasted the festival’s most nauseatingly obvious yet implausible dialogue.

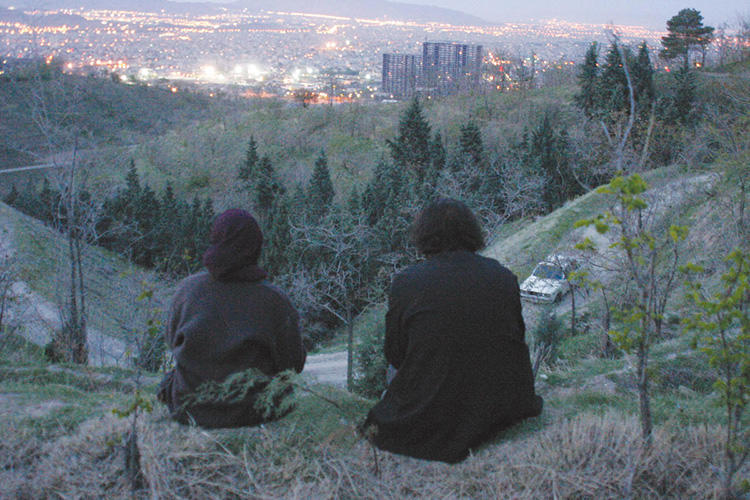

Still, there were bright spots both in the competition and the sidebars, even in a poor year for Middle Eastern films. While Mohammad Rasoulof’s Iron Island failed to win any prizes, it was a worthy closing night film in the Directors’ Fortnight sidebar. Set memorably on an abandoned tanker in the Gulf, it features veteran Ali Nasirian as Captain Nemat, a landlord who presides over the community of homeless, poor families on board. In an obvious yet compelling allegory of the disappointments of post-revolutionary Iran, Rasoulof gradually reveals that not all is as it seems: The more dictatorial than paternal Nemat is selling the sinking ship off for scrap piece by piece, and attempts by his young assistant Ahmad (Hossein Farzi-Zadeh) to assert his independence meet with a violent response. But this is no ham-fisted political tale: Rasoulof weaves an imaginative and well-paced narrative, ably assisted by Reza Jalali’s cinematography.

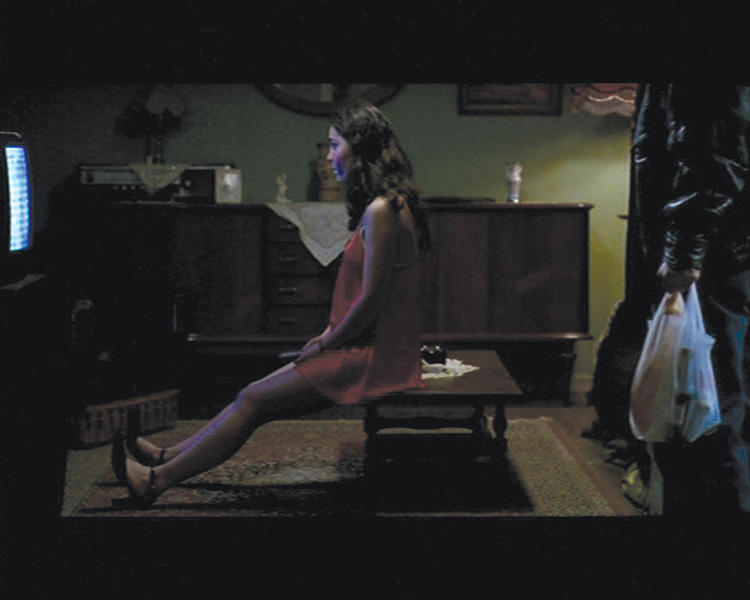

The other high-profile Iranian offering was matinee idol Niki Karimi’s feature directorial debut, One Night, a Kiarostami-inspired tale of Negar, a young woman (Hanieh Tavasoli) who spends the night on Tehran’s streets, hitching rides with three different men. While it tends to lose its way in the middle section, and includes some cheesy dialogue, Karimi has a bold style — outstanding scenes include the opener, in which she holds the camera still as Negar negotiates with her mother, waiting for her date, who remains unseen in the next room, and the end, when she again confidently freezes the camera as dawn rises over Tehran.

As another woman filmmaker from the Middle East, young Moroccan director Laila Marrakchi found Marock crassly lumped with One Night by some journalists but her teen tale couldn’t have been more different. Derivative and gauche at times, herfilm nonetheless presents a picture of mid-1990s Casablanca far removed from the “poornography” that represented Morocco in Cannes’ new Cinemas du Monde sidebar. The opening certainly sets the scene: Affluent, minimally dressed teenage clubbers make out in their flashy roadsters while a taxi driver prays, as the early 90s Snap number “I’ve Got the Power” plays in the background. Marrakchi’s cousin Morjana al-Alaoui plays Rita, supposedly studying for her end-of-school exams but more intent on partying with her Jewish neighbor/boyfriend Youri.

Marock was very obviously a debut, and it didn’t belong in Un Certain Regard, but the film will no doubt do well in France. It’s unfortunate that the sex and party scenes and overplayed Muslim/Jewish romance will preclude the film from screening in the Gulf, where a class of expat teens still live the affluent life that Marrakchi nostalgically pictures. She only touches on the upstairs/downstairs world of privileged Middle Eastern youth — Rita’s friends speak French to each other, Arabic to their servants—and the film leaves one crying out for someone to get going on an Arab Gosford Park.

The Iranian state Farabi Film Foundation always flies a bevy of representatives to Cannes, but the Arab world usually seems to miss a trick. With Hiner Saleem a loner, and Morocco with multiple films but no obvious country support, it was left to Lebanon to live up its stereotype and supply the PR panache. Although she had no films to screen, Lebanon was the only country to take a booth in the International Village, ostensibly to seek funding and promote projects in production. These include films by Danielle Arbid and Khalil Joreige and Joana Hadjithomas, which gives longsuffering Middle Eastern critics some hope for coming festivals.