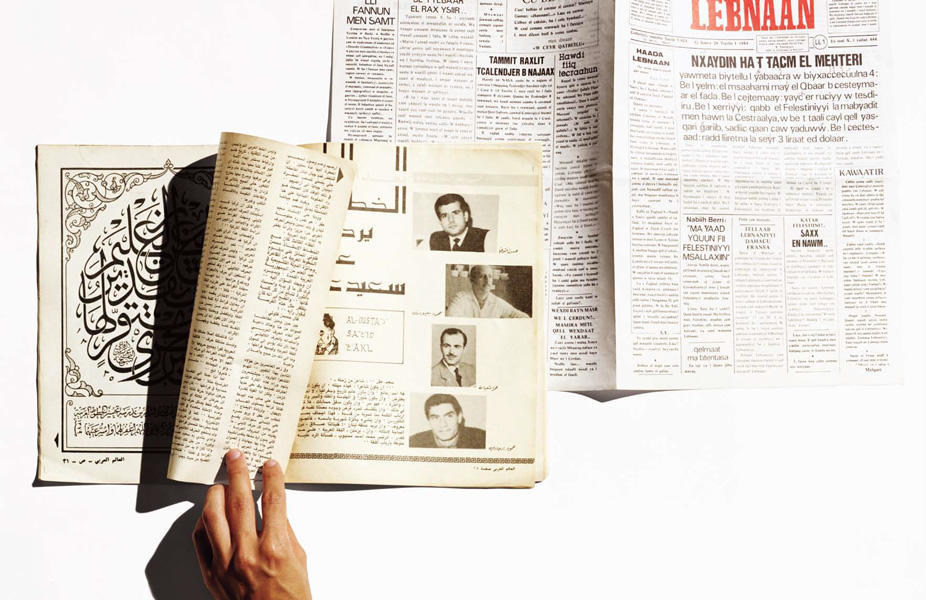

In the beginning, there were Phoenicians. More recently, there was Lebnaan, reminding the Lebanese of their beginnings. The paper’s founder and editor, Said Akl, deplored classical Arabic and printed his own language in its place: “Lebanese,” he called it, a Latinate version of colloquial Arabic, rooted in ancient Phoenician script.

Akl’s approach to the spoken Arabic was controversial from the start. Especially critical were calligraphers, who insisted that the language was inseparable from the script itself. But for Akl the Arabic language was the Lebenssprache of its speakers in their own place and time. He didn’t advocate a literal return to the language of the Phoenicians, but rather to the spirit of their contribution to all languages, the phonetic alphabet. He might have found more allies if he were not given to proclamations like “I would cut off my right hand just to not be an Arab.”

Akl signed his contributions to Lebnaan “Melqart, king of the city,” after the legendary demigod and protector of the Phoenician city of Tyre. His cosmology had a similarly epic scope. For Akl, Lebanon was the center of the universe, the seat of Canaan; its people, the ancestors of the Jews, had invented the written word, the color purple, and Europe.

Though Akl’s own personal journey was and remains idiosyncratic — it was the poet who suggested to General Michael Aoun to begin his speeches with “O Great People of Lebanon” rather than, say, “Ladies and Gentlemen” — his desire to create a new form equal to the task of representing contemporary speech was something he shared with many of his political enemies. A secularizing Pan-Arbaism was one of the forces driving the movement to formalize Modern Standard Arabic as a literary language not exclusively rooted in the Qur'an. A similar animus towards ecclesiastical authority led to the Latinization of the Turkish alphabet in 1928 as part of Mustapha Kemal’s modernization project. And a very different form of neo-Arabic has achieved far greater success across the Arab-speaking world — an unintended consequence of the rise of text messaging, whose practitioners deploy a combination of Roman characters and Arabic numerals to express the full range of Arabic consonants.

Lebnaan persisted for nearly fifteen years, despite finding limited favor among the people it aimed to seduce. (Not only was the language invented, it was an idiom specific to his hometown.) Yet it has readers. “In the Soviet Union,” vouched S. Yazimoov, the Soviet ambassador to the country, in a 1984 issue, “when we want to know what’s happening in Lebanon, we always read what Said Ald writes.”