Jerusalem

The Jerusalem Show Edition 0.1

Al-Ma'mal Foundation for Contemporary Art

July 9–19, 2008

There was no permit to enter Jerusalem. Not for the Ramallah-based artist Inass Yassin, whose specially commissioned paintings were on view at the opening of this edition of the Jerusalem Show, and not for myself. Still, we were both adamant about going, and after much brainstorming, we found an imperfect solution: someone would have to smuggle us. According to Ra’fat the driver, we needed an ajnabi, or foreigner, who would be willing to play the casual game of “salute the soldier” as we drove into Jerusalem. We found one, a Mexican artist who, oddly enough, was here exactly one year ago, at the first Jerusalem Show. So it was our Mexican “smuggler” who got us in after all, with a litter of laughs and much, much anxiety.

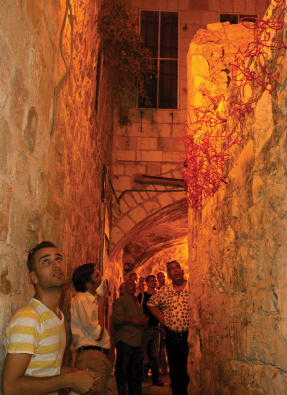

On opening day, some two hundred people were crammed into the alleyways leading to the Al-Ma’mal Foundation, anxiously awaiting curator Jack Persekian’s signal to start the tour. Inass Yassin’s paintings, hung in the old gallery rooms, made it possible to accept the long walk ahead. Her large-scale canvases — landscapes composed of pastel strips layered over drawings of buildings, rooms, or even banal Washingtonia palm trees — were stirring. In each painting, there was a subtle trace of migrating birds, almost as if they were passing from one canvas to the other. The birds seemed to signal a movement away from the claustrophobia of the urban.

This year’s Jerusalem Show came with a subtitle: Walks in the City. We found ourselves following Persekian around on one of the many walks led by him and others. I like to think of Jack as the ultimate flâneur in this context. How do you deal with a place laden with doom except with a fine dollop of humor, combined with a patience that can only be born of familiarity? How do you navigate a place that shuns you?

Perhaps by using the space as a tool in and of itself, by positioning oneself, literally, within its confines and walls. Artist Manar Zuabi, for example, installed red cable wires in the cracks of the walls in the city’s Alleys of Kisses (Zqaq Al-Bos), in a piece entitled O’shb Akhdar Akhdar (Green Green Grass). Nida Sinnokrot invited us to take a phantasmagorical journey searching for his light installation Untitled Cracks, composed of fairy-like firefly lights that shone a brilliant blue. These lights were positioned throughout the Old City, within the cracks of the walls, and were truly difficult to locate — which only made the search more satisfying.

Another piece took the architecture of the city itself as a point of departure — Sulieman Mansour’s Introducing the Other. Last year, the artist took portraits of people from both the Armenian and African quarters; he wanted to place the photos of the Armenians in the African quarter and vice versa. Apparently the Armenians refused, for no clear reason. It was going to escalate into a feud, and a sulha (settlement) had to be arranged in order to contain it. This year’s episode was between the Syrian and Roma communities. As far as we know, no drama resulted.

Sophie Elbaz’s impressive photos allowed us to visit a place at two moments in time. In 1991, she came to the area and took images in the midst of the first Gulf War. In the show, she juxtaposed images of the place, one next to the other, in a series of diptychs, allowing for their contamination via organic bacterial processes. Located in the depths of an abandoned bathhouse, these banal images were distorted by time and the elements — a welcome riposte to the stereotypical nature of imagery as it tends to be evoked in this corner of the world.

Tarek Al-Ghoussein’s Blue Diptych was composed of three projections onto walls. In one of the images, a solitary figure was juxtaposed against a blue shroud or tent, while adjacent to that image were two expanses of open desert land. At some points, the central image altered to show the figure engulfed by the shroud. Emily Jacir, in the meantime, presented Untitled (servees), a daytime site-specific sound installation in front of the Damascus Gate, composed of sounds of the “servees” (service taxi drivers) calling to take people away, from Jerusalem to Beirut, to Amman, to Baghdad and even to Kuwait. Her installation couldn’t help but evoke nostalgia for a lost mobility, a jostle of memories and goosebumps. A toast to the long-gone cosmopolitanism of a forgotten mecca.

Likewise, Luchezar Boyadjiev’s work seemed to epitomize many of the artists’ insistence on a lost cosmopolitan. The artist literally provided cinema seats on the tops of buildings in the Old City, in order to turn the viewer’s gaze to other cities. In his site-specific installation A City with a View(s), one found oneself encapsulated by the city, entranced by its limitations, mysteries, and tragedies.

Unfortunately, many artists seemed intent on falling into the trap of pity and forgiveness. Artist Henrik Placht, for example, should stick to his wonderful paintings, depictions of light and color from Jerusalem, and offer no apologies. I am referring specifically to his piece Apology, in which he installed the words “We Apologize” in red neon light on top of an old building in the Old City. He also had the word “Sorry,” written in Arabic, Hebrew, and English, distributed as pins for visitors to wear.

All of these works provoked important questions: Can we move beyond pity/piety? Can we look beyond the exalted image of what Jerusalem was, or are we destined to revisit it time and again, whether for the allure or just for the view?

Maybe pilgrimages in a place like Jerusalem are doomed to be endless hermeneutic loops toward an imagined past, exercises in nostalgia. The Jerusalem Show Edition 0.1 at its best gave us the opportunity to revisit such claims and think aloud about whether we could work toward a new version of the cosmopolitan — a strange one in which the Mexican with whom we began this journey may hold all the keys.