In December 1971, Iannis Xenakis penned an open letter to Le Monde, defending his participation in the Shiraz Arts Festival earlier that year. The Greek composer had created a massive sound and light show for the festival, part of the Persepolis celebrations, a thirteen-day extravaganza celebrating 2,500 years of Persian monarchy. It was his third time at the Shiraz Festival, but that year’s instantly notorious event provoked a hailstorm of criticism, not least from Iranian exiles in Paris.

In his letter, Xenakis cited his “deep interest in this magnificent country” and the “warm reception my musical and visual propositions have encountered there by the young members of the general audience” as primary motivations. But he also insisted that “it is impossible to name one single country that is truly free and without multifaceted compromise, without any surrender of principles.” Whatever “multifaceted compromise” Xenakis was willing to make to work for the shah, he was by no means alone. John Cage was a Shiraz Festival regular, and the 1972 festival was dominated by concerts by Karlheinz Stockhausen. (See “Ornament and Argument” in Bidoun 13 for more on Persepolis and the avant-garde.)

Nor was music the only focus of the ambitious arts program launched by Empress Farah in 1967. At that time, Iran coproduced a number of European and American films. In most cases the Ministry of Art and Culture provided funding — and sometimes backdrops or extras — but most of the films went nowhere, at great expense. (Orson Welles’s F for Fake is one exception; another Welles film, The Other Side of the Wind, was abandoned after the revolution). Most of the directors who made the trek to Iran to produce new work were given big checks and vague commissions; the particular concept of the work was less important than that it reinforce the shah’s projected image of a glorious and progressive Iran, at once ancient and modern. Participating filmmakers included Agnès Varda, Claude Lelouch, and Albert Lamorisse, the inventor of the board game Risk and the director of the beloved 1956 children’s classic The Red Balloon.

Lamorisse was commissioned by the Ministry of Art and Culture in 1968 to create a documentary interpretation of Iran. Like Xenakis, Lamorisse was enamored with the country. But whereas Xenakis took inspiration from ancient mythologies and artifacts of civilization, Lamorisse’s interests were of the spiritual variety. Contemporaries describe a gentle man, petrified of Tehrani driving and enchanted by mystical Persian poetry. He lived among a group of French expats with spiritual inclinations. He is said to have had premonitions of dying over water in the Caspian Sea.

The film he made, Le vent des amoureux (The Lovers’ Wind, often referred to by its Farsi title, Baadeh Sabah) is an aerial epic. Traversing vast, mainly rural, Iranian landscapes, the film is lyrically narrated by the voice of the Lovers’ Wind of its title. Lamorisse shot the film using Helivision, a steadicam rig he developed himself, especially for use with helicopters. Other contemporary aerial films used a camera mount that had the angle of surveillance pointing straight down. But in Lamorisse’s setup, the camera pointed forward, recording what approached. This forward view lends a slow, rhythmic pace to each long shot, allowing every subject to enter the frame at a distance before being filmed up close through a skilled combination of zooms and actual swoops-in near to the ground.

The effect, as Lamorisse and his crew graze over mountaintops, vast fields of grass, and ancient villages, can be dizzying — at times it’s difficult to tell if the wind being pictured is meteorological or an effect of proximity of the helicopter’s own propeller. In one scene, a magisterial view of hundreds of Persian rugs left to dry on a serene mountainside grows turbulent as the wind begins to disturb the rugs, eventually flapping them wildly into a sandy tumult, then gliding onward over a grassy field beyond, never looking back. The voiceover explains the scene as the working of Baadeh Div, the Evil Wind, who comes from between Baadeh Sabah’s legs, causing harm. (Other winds from Iranian folklore make appearance in the film, including Baadeh Sorkh, the Crimson Wind, whose force shapes mountains, rock forms, and islands too severe for humans to survive.)

Lamorisse’s decision to include a first-person narrative from the perspective of the wind itself neatly sidesteps the ethnographic dilemma many of his contemporaries faced when charged with documenting Iran, not only to the rest of the world, but to itself. The “we” of the voiceover refers to the Lovers’ Wind and its siblings; it also positions the narrator as a universal character, a myth that blurs the genres of travelogue and documentary.

Upon its completion, Baadeh Sabah was rejected by the Ministry of Art and Culture. The majority of the footage depicts pastoral landscapes, with the odd wolf or bird crossing through them. The first half of the film is almost entirely uninhabited by people, and the few who appear later are mainly farmers and nomads, a far cry from the students, intellectuals, and modern professionals the shah was looking to see. Lamorisse’s film was too soft-spoken, too folkloric; crucially, it showed none of Iran’s industrial triumphs. The shah called him back to shoot additional footage, which might then be stitched into the existing piece to create a fuller, more nuanced, picture of contemporary Iran.

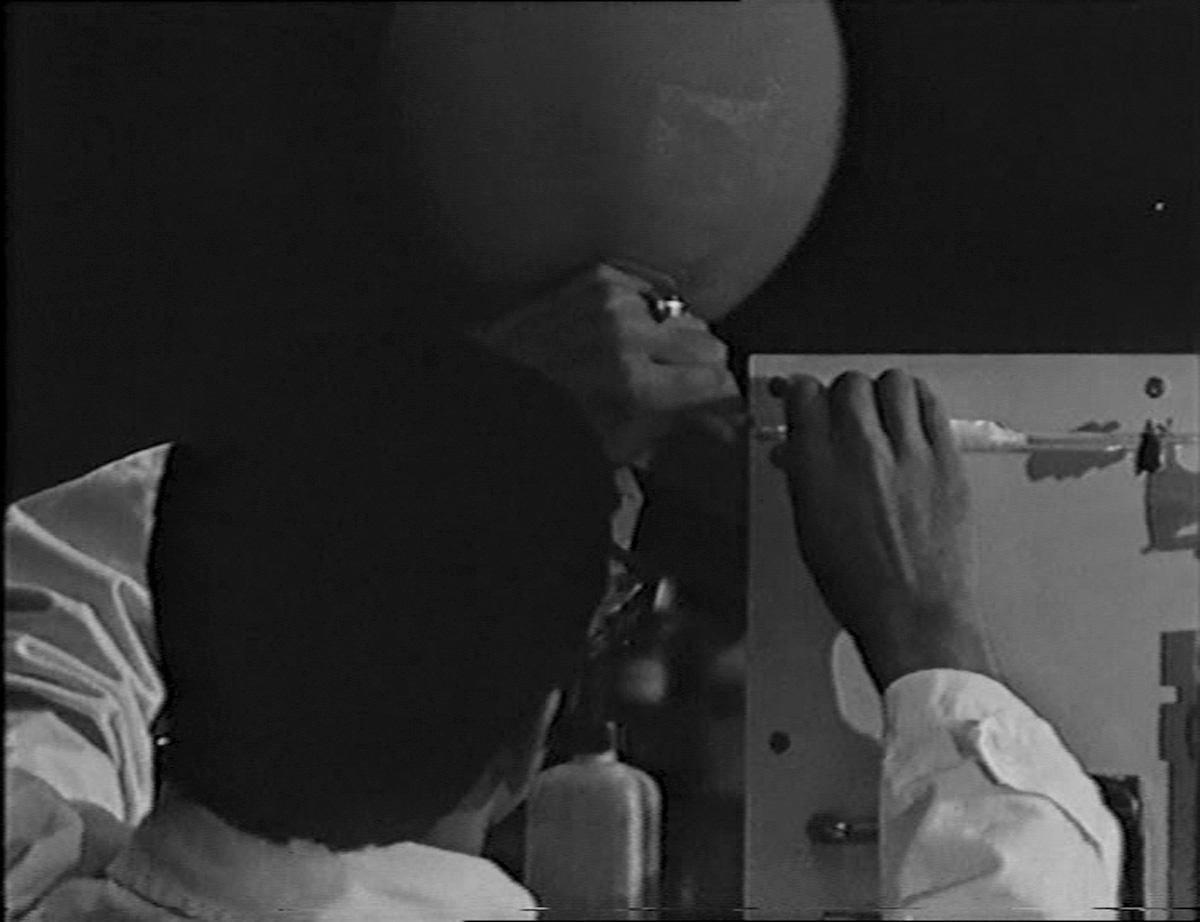

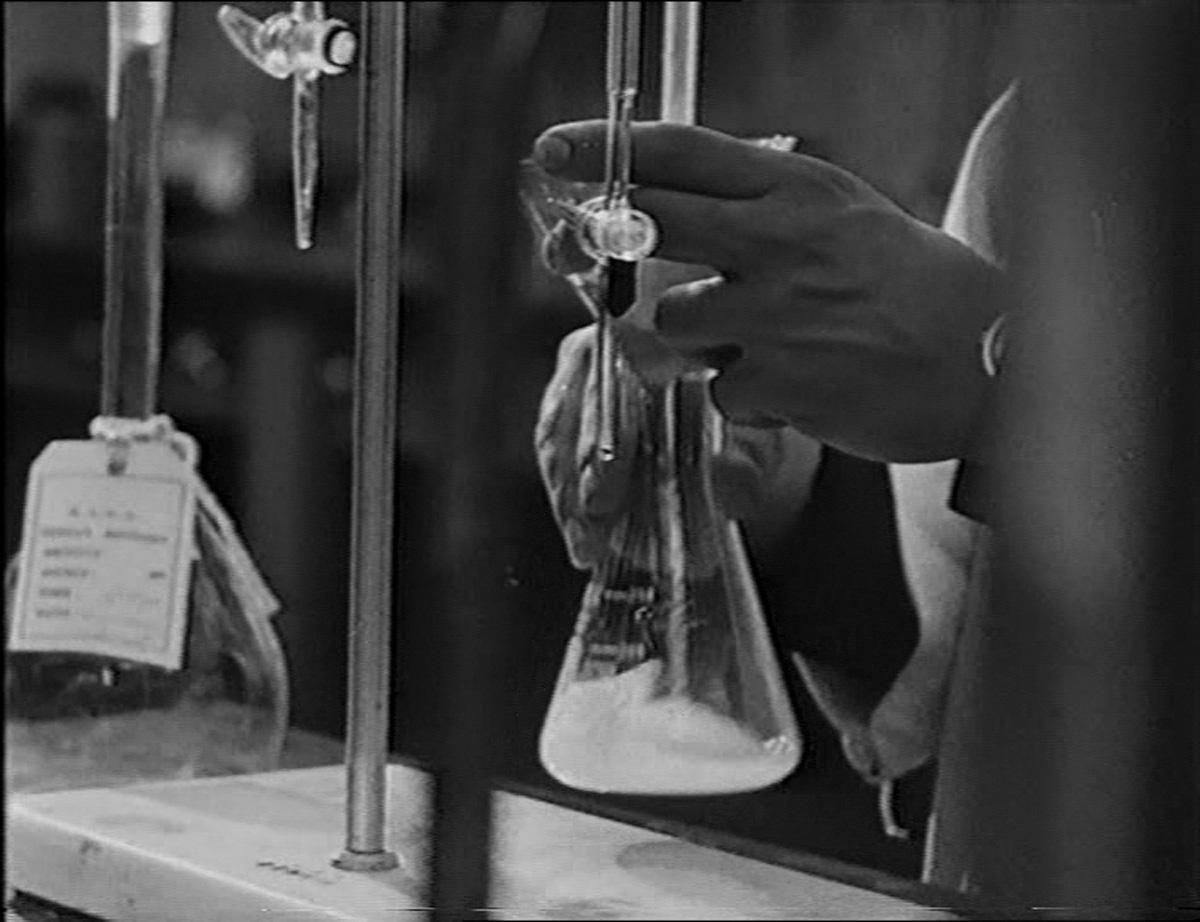

Lamorisse was reluctant. The ministry’s demands contravened the spirit of his creation, and while it offered to pay for his return to Iran, it refused to cover the costs for his crew; he would have to go alone. Further, this time the locations would be determined by the ministry: an automobile manufacturing plant, handsome and spectacled university students, laboratories with Bunsen burners and flashing doodads, the spectacular seventy-six million dollar Karaj Dam constructed by the Morrison-Knudsen firm of Boise, Idaho. He would have to use equipment provided by the Iranians, including the helicopter. Lamorisse made his “multifaceted compromise,” and he returned.

He was worried, however, about the locations — the dam, in particular. Flying a helicopter amid the high-tension wires above the water there seemed prohibitively dangerous, and he sent one of his assistants to register his concern. The ministry was insistent. But if it would make him feel better, they would provide him with the shah’s own personal pilot.

As it happened, Lamorisse’s apprehensions were well founded. Although it was not the Caspian of his premonition, on June 2, 1970, his helicopter got caught in the wires and crashed into the bright blue water of the Karaj River, killing Lamorisse, his crew, and the pilot.

Lamorisse’s family received a sizable compensation package, and the project was officially abandoned. Shortly thereafter, his wife Claude, and their son Pascal, finished the film following notes Albert had left behind. In 1978 it was finally released. It was nominated for an Oscar for Best Documentary Feature just months before the Islamic Revolution.

But there is a postscript to the story, in the form of a six-minute film. After the accident at Karaj, Lamorisse’s camera was retrieved from the wreckage and its film developed in the lab of the Ministry of Art and Culture. The footage was then edited together by Iranian members of his original crew to create a tribute to the director and a memorial of his death. The short, tacked onto the end of Baadeh Sabah in some of the bootlegs that are currently circulating, is prefaced with a message from the ministry (here translated from Farsi):

The renowned French director Albert Lamorisse was fascinated by the diversity of the vast land of Persia and the Iranian civilization. With his camera, Lamorisse captured the colorfulness of this country, and thus Baadeh Sabah was born by combining Iranian myths. But the allure of this land and the diversity of the historical cities portrayed in this story do not capture the progress of the contemporary society and the gap between the Iran of today and yesterday. Lamorisse came back to Iran once again to picture the lost thread of the relation between the contemporary Iran and the historic one in the film Baadeh Sabah, but destiny did not grant him the opportunity to finish it. For his commemoration, the production group decided to include in the film the last scenes directed by this great filmmaker. Thus the viewers could keep close to their hearts Baadeh Sabah as a precious keepsake from a man who loved Iran and Iranians.

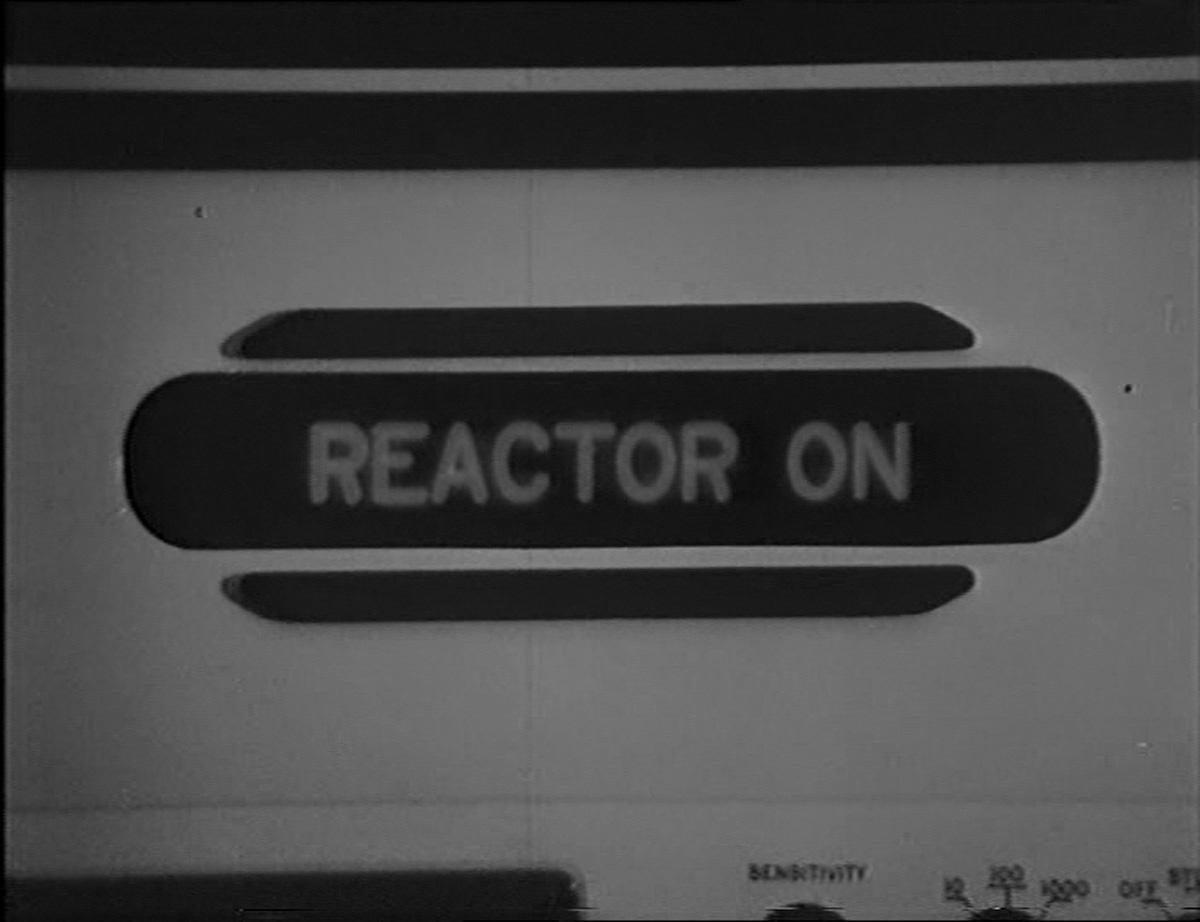

With its preface, the ministry declined to take any responsibility for the tragedy of Lamorisse’s death. But its eagerness to brush the incident aside may also have kept it from noticing the piece’s subtler implications — for the short actually painted a gravely sinister picture of the “Iran of today.” Although comprised of footage shot by Lamorisse, the tribute comes off in blunt contrast to Baadeh Sabah. The steady aerial glides are replaced by cold, hard, grounded images of factories, pipes, production plants — stock signifiers of progress. The editing is nervous and pronounced; at times the footage speeds up, while the music is tense and emotive. In the tribute, laboratories seem full of menace; the machines, soulless; the ambling students, zombie-like. The result is a hauntingly ominous and unsettling portrait of the shah’s coveted modernizations.

Midway through the tribute, the brooding electronic soundtrack gives way to a melancholy, minimal piano, and the anxious editing slows to repeated shots over the Karaj Dam — the final footage taken by Lamorisse before his death at forty-eight. Removed from its context, the short, like the feature, is beautiful and affecting. Inserted into Lamorisse’s personal story and the political narrative that had already begun to play itself out in the era of the Shiraz festivals, this “precious keepsake” is actually a jarring artifact of what may be the single most lucid allegory for the failure of the shah’s regime.

To watch these films, visit us on ubuweb