New York

The Road to Damascus: Discovering Syrian Cinema

Film Society of Lincoln Center

May 5–18, 2006

Cinephiles across North America have at last begun getting to know Syrian cinema after a prolonged obscurity for the country’s filmmakers, care of a touring retrospective packaged by the international arts nonprofit ArteEast. Having gestated fitfully for years, the series, titled The Road to Damascus or, alternatively, Lens on Syria, is at once the least bidden and most intriguing repertory discovery of the season.

The series encompasses nearly half of Syria’s total film output of the last thirty years — feasible because no more than two or three projects are completed annually, with virtually all production and distribution managed by the governing Ba’athist party’s centralized, Soviet-style National Film Organization. Redolent of Marcuse’s “repressive tolerance,” there’s just enough promise of artistic freedom to keep Syrian filmmakers negotiating a bureaucratic labyrinth, as decades wear past between finished films. (The Faustian turn is that praise garnered by those films that have sporadically surfaced in international venues may be leveraged indirectly as cultural capital by the Assad regime.) Nonetheless, the confounding and unifying trait of this daredevil cinema is its steadfast oppositional temper.

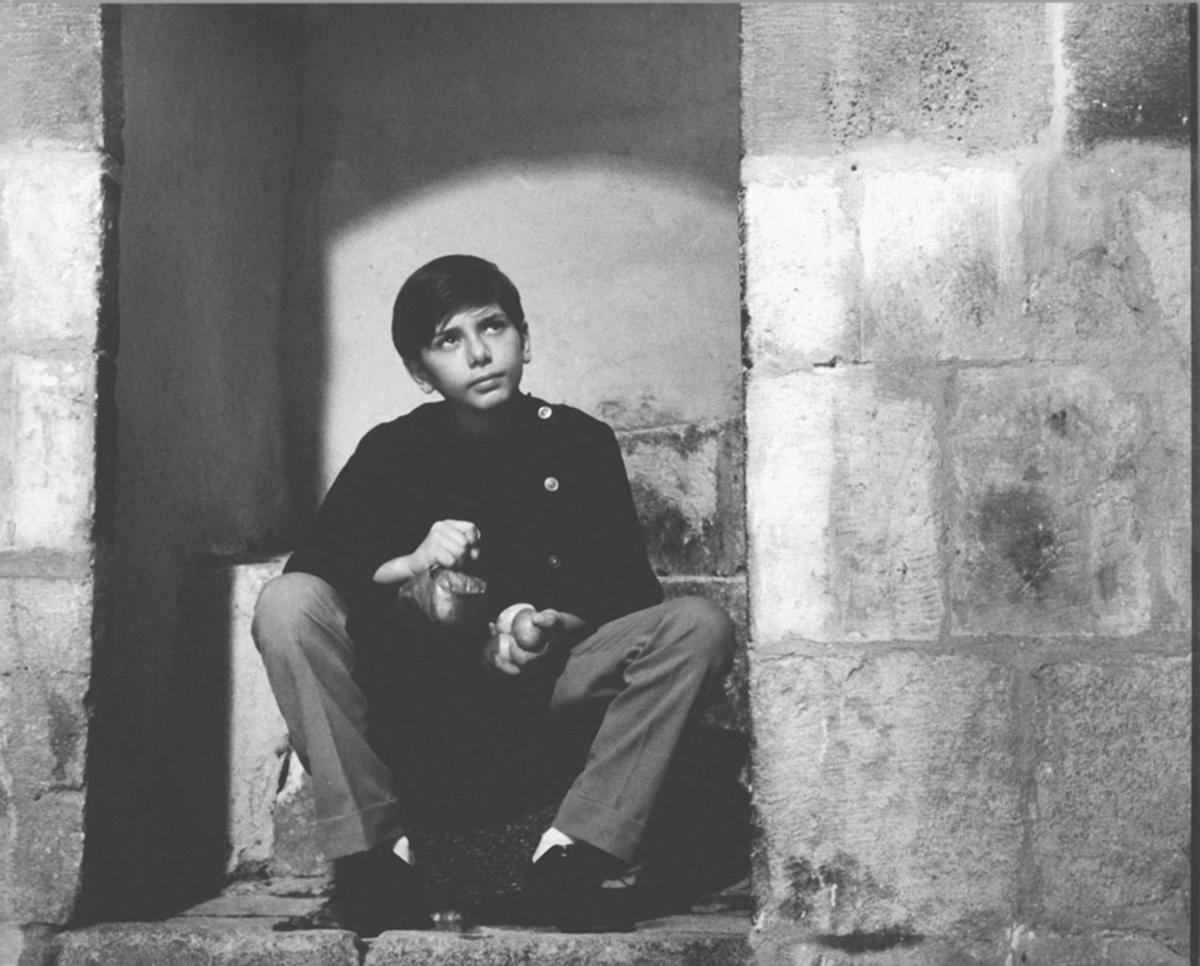

Besides making these hitherto elusive films available, the series also frames a canon, to the extent one has arisen from this straitened and politically isolated terrain. Included are all the milestones: The Dupes (1972), a Syrian production by Egyptian director Tewfik Saleh; Mohammed Malas’s Dreams of the City (1983); Oussama Mohammed’s Stars in Broad Daylight (1988); and Nabil Maleh’s The Extras (1993). Several of these directors share a sensibility marked by eidetic tableaux suggesting a private cosmology with affinities to the Symbolist poetics of Aleksander Blok. Indeed, Oussama Mohammed’s Sacrifices (2003) is a bucking tilt-a-whirl of Symbolist excess. An imposing, elderly patriarch expires without naming an heir, and the families of his three grandsons tussle in a delirious dynastic-succession allegory; viewers will leave reassured that their own kin are pillars of sanity.

Subject of a capsule tribute tucked into the series, the documentarian Omar Amiralay emerges as perhaps the most incisive talent in the cohort. Having decamped for a time to Paris on learning he was slated for state reprisal, Amiralay tapped European financing streams and honed the forensic method of his early efforts like Everyday Life in a Syrian Village (1975). The auto-critical impulse felt in many Syrian auteur films is most apparent in Amiralay’s later revisionist statements. A Flood in Ba’ath Country (2003) deconstructs his own naïvely triumphalist Film-Essay on the Euphrates Dam (1970), and There Are So Many Things Still To Say… (1997) retraces the setbacks of the Arab-Israeli conflict from the cancer ward where playwright Saadallah Wannous, Amiralay’s collaborator on Everyday Life, lays dying.

While there’s often a tumid quality to the features in this sense, the discipline of the short form has yielded at least two trim nonfiction masterworks: Amiralay’s The Chickens (1977) and Mohammed Malas’ The Dream (1981).

Resembling agitational “third cinema” in close-contrasted monochrome, The Chickens is a rapier portrait of assisted economic ruin. The desperately poor villagers of Sadad are induced with state subsidies to try their hands at poultry farming; blindsided by disease, overhead costs and their own cupidity, they end up facing demise. Amiralay skips from slicing windmill blades to a rotating Mercedes-Benz hood ornament to a lit-up hotel logo swiveling on an axis, mocking the villagers’ base materialism while associatively implying a chain of guilt. Elsewhere he graphically matches the honeycomb of stacked egg cartons with the vacant windows of freshly built proletarian housing blocks.

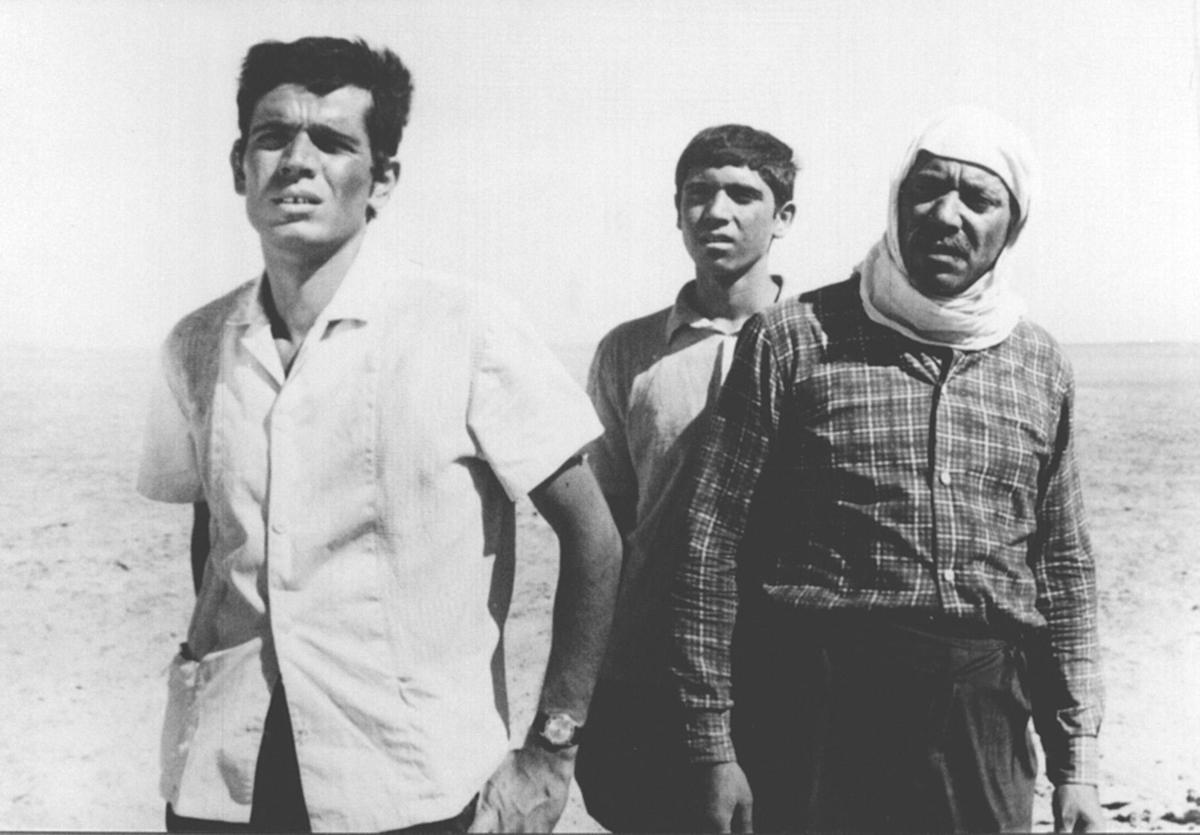

Malas was in Beirut a few months prior to Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon,and with a small crew visited the Sabra,Shatila, Burj al-Barajneh, and Ain al-Hulweh refugee camps, filming interviews with ordinary Palestinians, civilians and militants alike, most of them among the hundreds later massacred by Gemayel’s Phalangist militia on Israeli watch. The Dream is a rainbow at midnight, fearfully beautiful in stippled 16mm pastels, preserving the refugees’ voices and gainsaying their misfortune through recollected dreams interspersed with song (“Father, I have seen eleven planets”). One rickety matron shows off the makeshift carbine supplied by her son, declaring, “Of course it works!” There is disarming humor — one militant is seated before a poster of Che Guevara, their tousled manes merging in outline — and above all, a frank, easy fellowship, that in hindsight loads the film with tragic ballast.