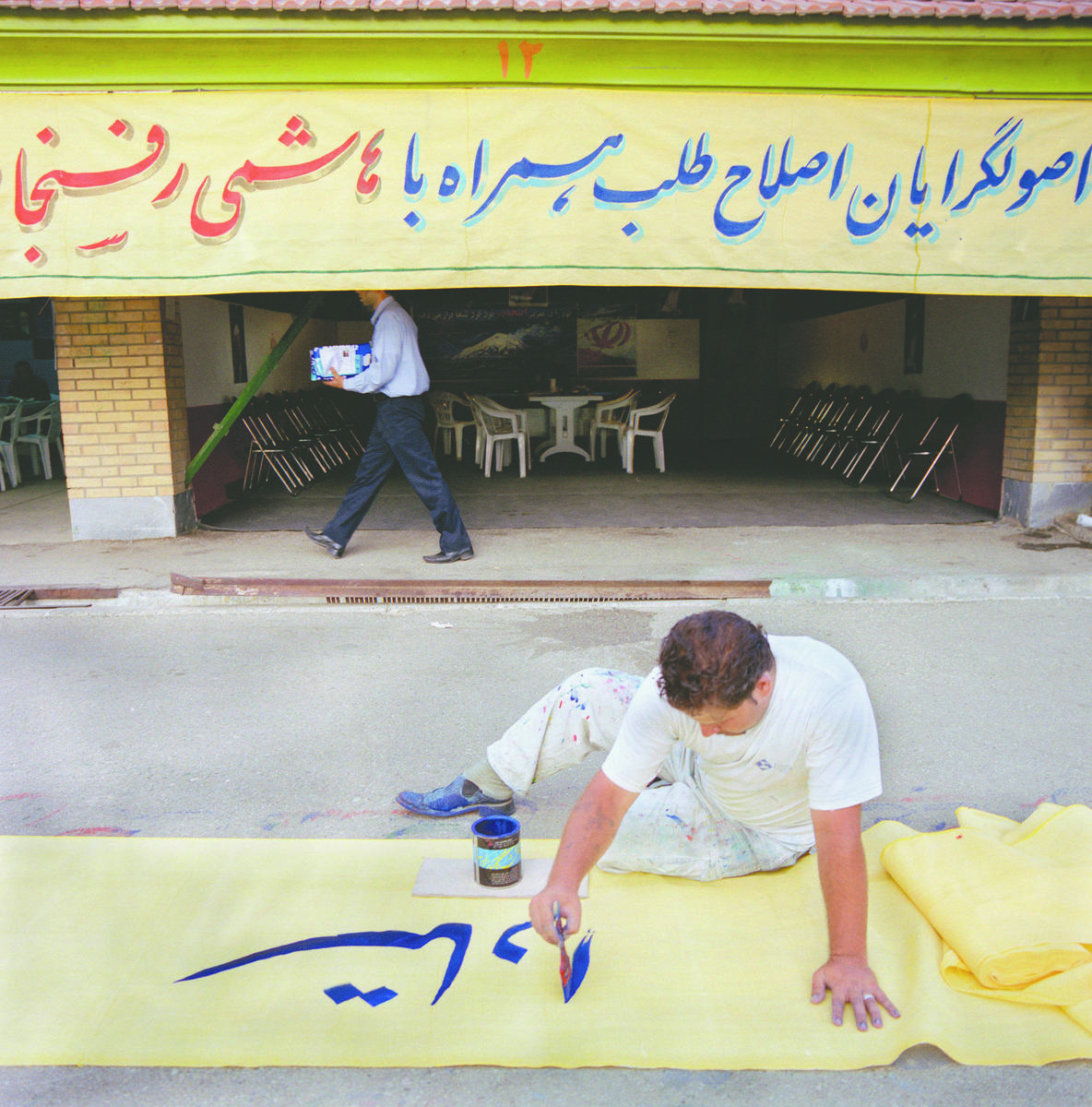

Ducking the election flyers thrust through my car window one evening, I found myself face to face with a shapely midriff. A teenage boy’s abdomen, undulating beneath a thin cotton t-shirt had been further tapered by campaign stickers for “Hashemi.” In last summer’s presidential election, several candidates pursuing the youth vote (two thirds of Iranians are under thirty) set out to capture Iran’s imagination by way of north Tehran’s designer teenagers. For police chief and Revolutionary Guard veteran Mohammad-Baqer Qalibaf, this meant sweeping his revolutionary credentials under the carpet and rebranding himself as a sharp-suited moderate in Ray Bans. For Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, a cleric and the hot favorite for the presidency, it meant paying uptown kids to drive around town in their parents’ sports cars, swathed in his “Hashemi” stickers, playing German techno on their stereos.

Just before the elections, the country erupted onto the streets after Iran’s footballers beat Bahrain 1-0 to reach the 2006 World Cup finals. That night I watched a blond siren dance on her car roof in front of a group of gyrating boys. Carried away by the euphoria of pre-election street festivities in a country where parties go on strictly behind closed doors, I and countless others were sure that Rafsanjani had it in the bag. The mood in Tehran had shifted tangibly, the youth were on the streets and the exuberance of those flag-waving football fans seemed certain to carry him and his promises of economic liberalization and continued social freedom to victory. My tip for second was Qalibaf. I’m not sure I could have told you what he stood for, but I was won over by his casual-cool wardrobe and his slick graphic design.

I had no idea that a diminutive blacksmith’s son from Garmsar, whom commentators had written off as a right-wing oddball, would mobilize seventeen million Iranians to vote him into power — silencing the stereos. While allegations of vote rigging and coercion by the Revolutionary Guard hover over Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s passage through to the second round of voting, it’s hard to argue with the decisive sixty-two percent of the vote with which he trounced Rafsanjani, the Godfather of Iranian politics, in the run-off for the presidency.

With the luxury of hindsight, the wrap around sunglasses and long haired poster boys of the Rafsanjani campaign seem a miscalculation: the emphasis on the youth vote had been a red herring. Ultimately it was not the lop-sided demographic of Iran but another statistic that turned out to be the key to the election: high unemployment, fifty-two percent of which is that of youth.

Rafsanjani tried to stir up hype around a kind of Ronald Reagan “trickle-down” model for wealth creation. Ahmadinejad’s supporters wore looser t-shirts and tighter headscarves and were unconvinced by Rafsanjani’s intentions to open Iran to the free market economy. Like the surprise win of India’s Congress Party in 2004 over the BJP’s India Shining campaign, Iranian voters chose a man who at least promised to look after the poor.

Nationally broadcast campaign films became the wider arena for jostling between candidates. Rafsanjani asked filmmaker Kamal Tabrizi, fresh from the success of his film The Lizard, to produce two campaign videos. The Lizard is a comedy about a thief on the run who dresses up as a mullah, and Tabrizi was a brave choice for the cleric whose wealth is rumored in the mega millions. The films, however, were duds. Farcical depictions of the loneliness of power, Rafsanjani weeps on camera in one sequence, while a young girl talks about her disillusionment with Iranian politics. As contrived as the tears were, the films soon became a laughing stock.

Meanwhile Ahmadinejad chose his university contemporary, film maker Javad Shamaghdari, to make his election broadcasts. Director of Love and the Sun, an adulatory biopic of Ayatollah Khomeini, Shamaghdari was determined to make a film of which the Islamic Republic’s first Supreme Leader would have approved. His un-flashy and seemingly un-spun filmmaking struck a chord with the electorate. Unlike other candidates, Ahmadinejad didn’t bother with the catchphrases of “democracy” and “human rights.” For Hossein Kermani, a student and member of the Basij, Iran’s volunteer force whose block vote helped propel Ahmadinejad into the second round, these are “meaningless phrases imposed on Iran by the West.” Instead, Ahmadinejad’s film talked up “social justice” and his determination to serve “the people” before he hugged a distressed Azeri farmer with financial problems and promised, in the farmer’s own language, that he would sort things out.

For Qalibaf, however, the “big mistake was to dress up like a commercial rather than a military pilot,” said Shamaghdari, whom I met in his office at the Society for Islamic Arts a month after the election. “People know he’s a pilot because he flew MiGs in the Iran-Iraq war, and it was a mistake to try and hide it.” Shamaghdari, in the meantime, played up Ahmadinejad’s credentials as a war veteran (he ran covert missions behind enemy lines during the eight year conflict). The scene in which he hugs a chador-clad mother who lost three sons to the war brought tears to the eyes of many, among them Basij veteran Hossein Mohammadi. Only sixteen when he was hit by Iraqi fire, Mohammadi lost both legs and a brother at the front and now maneuvers around Tehran in a wheelchair and a converted golden cadillac. He feels that with Ahmadinejad’s presidency, “Our time has come. Ahmadinejad will make our sacrifice count for something again.” Staring at his brother’s portrait on the wall, he tells me “Look at Tehran’s streets. They are full of lost kids in bad hijab doing drugs. Khatami called it freedom but I call it a prison of sin. Ahmadinejad has come to bring them home.”

Mohammad and others describe Ahmadinejad’s victory as a second revolution, the only difference being that the ousted ringleader of a corrupt elite was wearing a clerical turban and not the Pahlavi crown.

Shamaghdari’s film could not have been more explicit about Ahmadinejad’s attitude to conspicuous consumption. After a tour of Ahmadinejad’s simple house in the unfashionable district of Narmak, his camera took us, like voyeurs, through the empty halls of the mayoral mansion occupied by Ahmadinejad’s predecessor, but later donated by him to the city. As though entering the scene of a crime, we creep past the marble staircase and the chandeliers, through the French windows to the swimming pool and sauna. The horror of the material nature of it all!

Shamaghdari compiled a rousing soundtrack for his film. He plucked tracks not only from Spygame (Iran has no copyright law) but also from Oliver Stone’s Alexander the Great: “Alexander put out the lights on the Achaemenid Empire’s party.” Ahmadinejad put an end to Rafsanjani’s.

One campaign poster of Ahmadinejad announced his zero tolerance on corruption like a call to arms: a row of images showed a colonnaded villa, a high security wall and a flashy Mercedes Benz, while underneath them scrawny kids in a hatchback are sandwiched between a shack and a mud partition. Twenty-seven years after a revolution that was meant to close Iran’s social and economic divide, the poster mainlined the same bitterness as images from 1979. That year, photographer Kaveh Golestan plastered black and white photos of child workers and destitute orphans to the walls of Tehran’s University. He wanted to draw the world’s attention to what lurked behind the pipelines and glittering parties of the Shah’s oil aristocracy. Golestan’s photographs were put up a stone’s throw from what became Revolution Square, the epicenter of the uprising that sent the monarchists packing and ruined the Pahlavi party.

Today, Shamaghdari’s office is two streets away from that square where he once marched as a student activist. His calm demeanor as he asks me to leave my shoes by the door belies the excitement he feels to be at the center of this “second revolution.”

Iran’s eight years of progressively freer social codes are over and Ahmadinejad is now busy implementing his particular vision for Iran. Nuclear capabilities aside, he has sent the presidential carpets to the National Museum, moved the receptions for visiting dignitaries from the Saadabad Palace in the north of the city to offices in mid Tehran, and arranged for arrests of oil executives on charges of corruption. A young bearded man in an Islamic Republic souvenir shop sold me his last poster of Iran’s new president because “Ahmadinejad wants the paper to be used for school books instead.” He was excited to be part of a movement “that will bring justice and jobs to the people of Iran.” The message, like the films, appears so straightforward.

Heavy on words like “justice” and “equality” and much lighter on detailed plans to tackle inflation and create jobs, Ahmadinejad’s campaign, however, left plenty of room for speculation as to what the future holds. Along with much of the world, the upper echelons of Iranian society are less enthused by new developments. Nervous of Ahmadinejad’s seemingly antagonistic approach to relations with the West and worried by the specter of wealth redistribution, my better heeled acquaintances are relieving the tension with jokes about their new president’s personal habits. The election has certainly touched up the paint on old battle lines, and whether you laugh at the punch lines or glower at the insult depends on which side of Iran’s enduring social divide you stand. Ali, a student at Azad University, spent his twenty-first birthday in the company of the Basij after they broke up his party and arrested him and his friends. “They hate everything about us,” he says about Basij vigilantes whose nighttime terrorizing tendencies have stepped up noticeably since Ahmadinejad’s victory. “They don’t want what we have, but they can’t bear for us to have it.”