I bought my first accordion in Ukraine. It was shiny and red, small enough to carry back on the plane to New York but with a big sound, bright yet mournful. I could bring that little accordion anywhere. “Hey, weren’t you the one playing accordion?” People would say. From impromptu shows in Philadelphia and Estonia, I discovered that my accordion could start conversations where I thought I had nothing to say.

In 2007, I got a fellowship to report in Afghanistan. As my date of departure approached, I started to freak out. What did I know about Afghanistan beyond what anyone could see on the news? I didn’t speak Dari or Pashto. And if there had ever been a good time to be an American in Kabul, that time was over.

So I had brought my little red friend with me when I landed at Kabul Airport. Customs gave me a raised eyebrow but let me through. A few days later, on a freezing Kabul night, I was typing up some notes by the woodstove in my rented living room. My colleague and translator Najib lay on his back doing abdominal crunches. He’d fling his legs into the air with a loud grunt; another guy, a house guard, would grab them and fling them back down. The room was dead quiet except for his exertions. I went and got my accordion, and Najib seemed thrilled — he started doing his crunches even louder and faster. I played another song, and then a third, and that’s when Najib stopped, looking surprised.

“Hey!” he asked with a smile. “How do you know Afghan music?”

I looked at him, utterly confused. “This isn’t Afghan music,” I said.

“Yes, it is!”

“No, it’s not — this is a folk song from the 1960s called ‘Those Were the Days.’ My mom used to sing it.”

“No!” he insisted, equally confident. “That song was famous for being sung by a singer who was our Casanova. His name was Ahmad Zahir. Famous Afghan singer.”

He and the guard sang the song for me. It didn’t sound anything like the song I knew, and as a result, I dismissed the incident.

But then the same thing kept happening. Every time I played my songs for people I met in Kabul, they’d say, “Hey, isn’t that by Ahmad Zahir?”

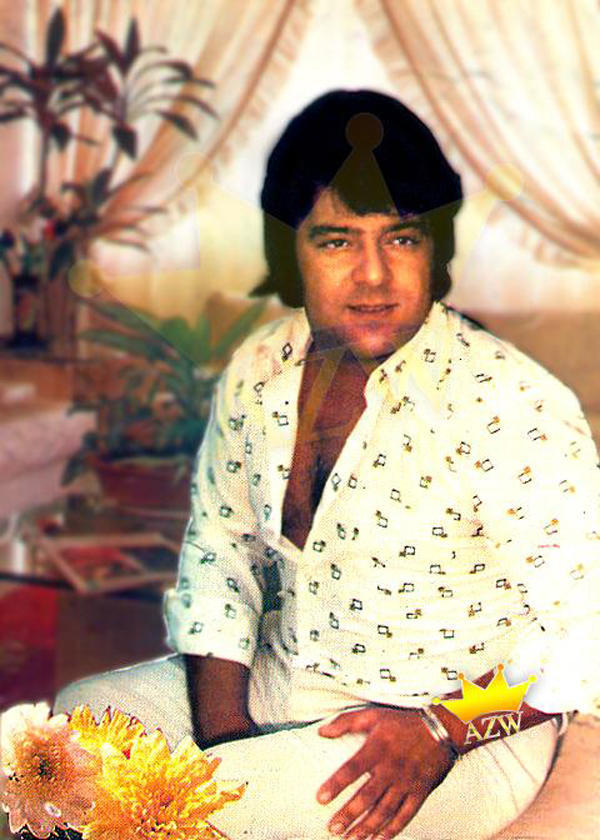

I asked Najib to help me do some research. He handed me a CD collection of Zahir’s music. Each colorful CD sleeve featured a stout Afghan man with smoldering eyes, a cocksure smile, and thick sideburns. The ’burns and his big pastel collars made him look a lot like Elvis Presley. “They called him the Afghan Elvis,” Najib said.

I put on the first CD. Zahir’s songs had all the elements of traditional Afghan music: the tabla, the wailing strings of the dumbra, the crooning vocal style. Yet as I listened to more of his records, I heard one Western riff after another. There was a lot of Elvis, yes, but also John Lennon and Nat King Cole. Some of the melodies seemed like Afghan versions of Western songs. When I listened to the song “Tanha Shodam Tanha,” the one Najib thought sounded like the song my mom used to sing, it did sound familiar. I emailed the track to a friend in St. Louis, who wrote right back: Oh yeah, that’s an old Western disco hit, “El Bimbo.” He was right — it was “El Bimbo,” same melody, same key. But something didn’t fit. “El Bimbo” had been an international hit in 1975, recorded by a pair of French guys who called themselves Bimbo Jet. But “Tanha Shodam Tanha” was the big hit from Zahir’s album Lylee, released in 1971. So Najib had been partly right. Even as Ahmad Zahir was cleverly, lovingly Afghanizing everything from Elvis to folk rock and film scores, at least one of his songs was being craftily, cannily Westernized.

I insisted that Najib tell me more of the story, though it turned out almost anyone could have told me about Zahir, one of the best-loved figures in Afghan history. His father had been a diplomat and politician and had hoped his son would follow in his footsteps — which he did, after a fashion. Zahir toured several neighboring countries, including Iran in 1973 at the invitation of the empress. And his lyrics, some of them based on folktales and old ghazals, were interpreted as radical by the government as well as his legions of fans, some of whom began to call him the “Conqueror by Music.”

Najib then drove me to the outskirts of Kabul, where we knocked on a locked gate — a piece of corrugated tin — until a man with white hair opened up. This was Sadat Dardar; he’d known Zahir since the fourth grade. The gate closed behind us, and suddenly the scene changed: we walked out into a garden with flowers and a small pond. Dardar pointed to a moss-covered stone fountain. He said something to Najib, and Najib started laughing. “He says, this is the fountain where Ahmad Zahir used to sit and play his accordion,” Najib translated. “And forty girls were lying around here listening to him play.”

While I processed this news — Ahmad Zahir played accordion? — Dardar recounted the dark end of Zahir’s story. In the 1970s, as the winds of change swept over Afghanistan, his freedom-loving lyrics and his fiercely apolitical stance infuriated some in the government, especially the Communists. The Communist Party would ask him to play its dreary political showcases, and he would refuse. At the same time, his own concerts were always sold out.

In 1978, Nur Muhammad Taraki seized the presidency with the help of the Soviet Union. Many of Zahir’s friends fled the country and urged Zahir to follow; there were murders and rumors of torture in Taraki’s secret prisons. Taraki had a personal grudge against Zahir and had him arrested a number of times on various charges, though nothing he did could diminish the singer’s popularity. When Taraki’s own daughter was getting married, she demanded to have Zahir play at the wedding. She didn’t know that Zahir was, at that very moment, sitting locked up in one of her father’s prisons. President Taraki begged her to accept any substitute, but she stamped her foot and demanded Ahmad. So Taraki had little choice. He sent his officers to Zahir’s cell. The singer agreed to perform but refused to change out of his prison garb. The ballroom crowd gasped as he strode onstage in a dirty uniform and started to sing. Women swooned. The president seethed.

On June 14, 1979 — his thirty-third birthday — Ahmad Zahir was killed. The government said he had a traffic accident; everybody else says he was shot in the head. News spread through the country like a shock wave. Young girls committed suicide. Mourners were so numerous at his funeral that people were trampled in the crowd. Later it was said that when Ahmad Zahir died, he took the light of the country with him. A few months later, the Russians invaded, and Afghanistan plunged into war. The war with the Soviets was followed by civil war, and then by the Taliban. The Taliban tried to obliterate popular culture. They banned instrumental music and destroyed the small monument that had marked Ahmad Zahir’s grave. Only when American troops arrived in 2001 did the radios came back on. And whose voice came out of them? Three decades after his death, Zahir was still the top-requested artist on Afghan radio stations. His iconic style reminded Afghans of happier times.

For me, Ahmad Zahir was an unexpected entrée into Afghan culture. It was as if, when I played my music, music I thought of as my own, Afghans heard it as something uniquely theirs.

I experienced this a few weeks after that first performance for Najib. I was up in the northern Afghan city of Mazar-e-Sharif, reporting a story for National Public Radio about a big music festival there. I came to the last standing theater in the city, where one of the bands was playing traditional Afghan music. I had brought my accordion with me, thinking I might get the chance to jam with some musicians after the show. But being the only Westerner in the room, I stood out, and the festival director saw my instrument and asked me to perform.

I didn’t know what to say. These men in the audience were not Western-educated types like Najib and his friends. These were traditional men who had come to see traditional music. Then a short man with a long beard was shoving me onstage. I introduced myself to the crowd, and then I played a song I knew well, by the late great American singer Johnny Cash. The tune was “Ring of Fire.” I hit the chorus and the whole theater went wild. They cheered and clapped so loudly I could barely hear my own voice. I pumped my little red accordion as loudly as I could. “Drowned, by desire,” I sang.

“I fell into a ring of fire.”