Film festivals, where screenings begin at 8:30am to the groggy, jet-lagged dismay of critics, are not always the best places to debut a film. Between the early starts and the five-hour cine-essays about ethnic abjection or industrial ruin, it’s easy to get jaded. Still, the highlight of this year’s Cannes Film Festival, for me as for many of the assembled pen-pushers, was Waltz with Bashir.

Directed by Ari Folman, it’s an animated documentary about the massacres that took place at the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in 1982. Those massacres are hardly unknown; indeed, they were declared acts of genocide by the United Nations General Assembly in December 1982 and led to Ariel Sharon’s dismissal from the post of defense minister. Folman’s innovation was to use them as the apocalypse of a more personal narrative based on his own experiences as a draftee.

Waltz with Bashir begins with him, now an established writer and director, confiding to a friend a recurring nightmare in which he is chased by savage dogs. This is interpreted as having something to do with his military past, a past he has blocked out over subsequent decades. He decides to track down and interview fellow IDF soldiers who were serving at the time and who bore witness to the bodies of the dead, in order to recover, or at least reconstruct, his lost youth. The stories he hears — about shooting and being shot at, about the disdain many of them held for Palestinians — amount to a form of “memory work,” an anti-Grand Tour of his ballistic biography.

The film, realized with the help of art director David Polonsky and animation director Yoni Goodman, was initially conceived as a small-budget short. Four years and two million dollars later, Folman had created a bold synthesis of investigative documentary and arresting animation. The voices of his interviewees, among them a falafel magnate living in the Netherlands and a karate-chopping, patchouli-oil-addicted tough guy, have been retained, their stammers, mumbles, and testy pauses lending grit and texture to their words.

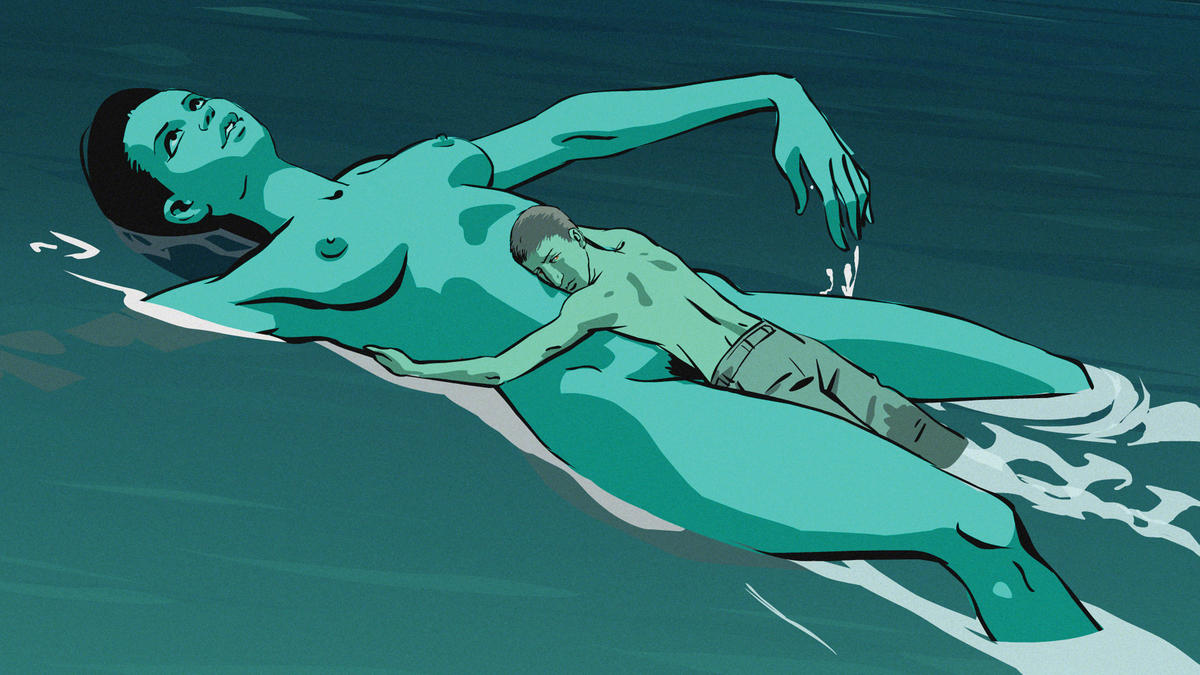

Waltz with Bashir’s ninety-page script was filmed with live actors and the footage hand-drawn by a team of artists working at the rate of six minutes of the story per month. What makes the finished work so arresting, though, is its skill at depicting the surreal, jumbled-up lives and experiences of its callow teenagers. Startling images of dying horses and a young girl’s head sticking out of the rubble are supplemented by bawdy sequences in which soldiers watch porn films involving German plumbers and trippy, hallucinatory scenes in which Folman dreams of resting his head on a giant, naked woman floating out to sea.

Elsewhere, OMD’s “Enola Gay” provides the soundtrack for soldiers on a commando boat, hollering cheerfully, in a heady evocation of soon-to-be-lost innocence; images of Sharon are underscored by PiL’s “This Is Not a Love Song.” Paranoia, the discombobulation of war, the difficulty of recovering authentic experience from the distortions and erasures of the media archive: the film resembles, and certainly mines themes explored by, Richard Linklater’s A Scanner Darkly.

Some critics have remarked, acerbically, that few Palestinian directors would have been financed to create this withering a denunciation of the Israeli war machine. Others have quibbled over the film’s treatment of some of the more nuanced historical details. But that shouldn’t take anything away from the boldness or artistic success of Folman’s undertaking, itself part of a wave of recent Israeli documentaries — among them Ari Libsker’s Stalags, an exploration of the early-60s vogue for Holocaust porn, and Jonathan Ben Efrat’s Six Floors to Hell, about Palestinian illegal migrants scrabbling for jobs — that are willing to enter and navigate paths through previously hidden corners of Israeli society and culture.

There will be those who fundamentally disagree with Waltz with Bashir’s suggestion that Israeli soldiers were as much victims of their nation’s war machine as they were its agents. Yet it seems to me that Folman already dramatizes vividly the fuzziness and sometimes elusory nature of ascertaining truth — especially around such a historically contentious event. There is something valuable, too, in seeing the history of the massacres from the point of view of the aggressors, and in the way Waltz with Bashir poses for Israelis the question of how to engage the legacy of shameful memories perpetrated in their name.