You can buy everything with money except a gold medal.

—The Iron Sheik

Every 1,000 years, history gives us one Michael Jordan, one Muhammad Ali… and one Iron Sheik.

—Eric Simms, ESS Promotions

One hot, sticky afternoon last May, the former professional wrestler known as the Iron Sheik stood before a full-length mirror in his home in suburban Fayetteville, Georgia. Later that evening, before a not-quite-sold-out crowd, the sixty-six-year-old would be inducted into the National Wrestling Alliance Hall of Fame at Atlanta’s Philips Arena. He examined himself from the front, the side, the back. He has always been a large man, but over time his vast Herculean figure has gone soft, settling into a less distinct, though still formidable, girth.

He wore a blue pinstriped suit, a brightly colored vest of ambiguous ethnic origin, and a red and white checkered kaffiyeh on his head. Around his neck hung a gold medal he won as a Greco-Roman wrestler at the Amateur Athletic Union national championship in 1971. It is easily mistaken for Olympic gold, which is, of course, the point. The Sheik, pronounced “chic” by his followers, massaged his twirly moustache with a dab of gel. “Let’s eh-go,” he said.

One hour and one trip to the liquor store later, he rolled up to the arena’s back entrance with an entourage that included his agent Eric and his driver Eddie, a chronically stoned Puerto Rican with an extravagant lisp who never seemed to be in any condition to drive. Five young fans stood outside a modest barricade, dressed in black and waving publicity photos of the wrestler performing his trademark move, the “camel clutch.” They yelled “CHIC! CHIC! CHIC!” as he lumbered out of the car. He turned to one of them and offered a wide grin, revealing huge white teeth. “Okay, Baba, who is the best? Who is the best, Baba?” They yelled again, “CHIC! CHIC! CHIC!”

Like Bon Jovi, Margaret Thatcher, and Don Johnson, the Iron Sheik is a product of the 1980s. The 80s were his decade, his coming out, his alpha and his omega. On December 26, 1983, not three years after the release of the last of the American hostages in Tehran, an Iranian would take home the crown jewel of the wrestling world in a title bout that would change the sport of wrestling forever. It took all of ten minutes. The Sheik slammed, suplexed, clotheslined, pinned, and washed and dried six-time reigning world champion Bob “Howdy Doody” Backlund until his manager threw in the towel, leaving the former champion splayed out motionless on the sweat-drenched mat. “Victory!” cried the Sheik’s manager, “Classy” Freddie Blassie, as he leapt up into the ring. The audience was aghast. It was the dawning of a weird and occasionally twisted age that wrestling’s most ardent fans still refer to as “the golden era.”

But who was this camel-clutching, curly mustached, genie-booted Iranian who had taken the world by sandstorm?

Hossein Khosrow Ali Vaziri was born on March 15, 1943, in the South Tehran neighborhood of Char rah-e Galobandak, not far from the capital city’s labyrinthine bazaar of carpet dealers, tea merchants, and hustlers. His father, Haji Ghasem Vaziri, was an illiterate farmer who grew pistachios outside the city and wrestled in the neighborhood zurkhaneh, or traditional wrestling house. Hossein had a sister named Masoumeh and two brothers who were named after the prophet’s sons, as he was.

Iran in the 1950s and 60s was a country of stark contrasts. While the vast majority of Iranians carried on with their traditions — toiling on the land, marrying children off to their cousins, saving up for a decent burial spot, and so on — the country had become an especially sweet place for people with money. Under Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi’s tight-fisted rule, oil prices were soaring, expatriates headed many of the country’s schools and companies, and rich young people socialized in the fashionable clubs of Lalezar Street.

At the time, the country’s greatest hero was a wrestling legend named Gholamreza Takhti, a four-time Olympic gold medalist who, like Vaziri, had spent his childhood in the neighborhood around the bazaar. Vaziri and Takhti could almost have been brothers, with their square jaws and puppy-dog eyes. It was this heroic doppelganger that inspired the scrawny fifteen-year-old Vaziri to try his hand at wrestling. Later he would have the number 90 tattooed onto his right arm, just below the elbow: Takhti’s weight in kilograms when he won his first Olympic gold. Takhti was, in Vaziri’s words, “the greatest eh-wrestler in the history of the eh-Persia.” (Like many Iranians, Vaziri adds a telltale “eh” before most any English noun.) “I wanted to show my parents I could be big just like him.” Three years later, following in the illustrious footsteps of his hero, Vaziri won the national high school championship in both freestyle and Greco-Roman wrestling.

Vaziri next joined the military for his mandatory national service, where he swiftly took the army wrestling championship. He went on to work as a technician for the state television, occasionally tending to the lighting at fancier events such as state visits and concerts. When the Empress Farah Dibah launched her avant-garde arts festival in the city of Shiraz, Vaziri was picked out of the crowd to work as a bodyguard. A sequence of black and white photographs he keeps in clumsy plastic covers, Weegee-like in their accidental art, sit in his home as a trace of that time. There is the empress with her exquisite cheekbones, surveying a modern art exhibition of some sort, and there is Vaziri in the corner of the photo, stone-faced, a curious footnote to someone else’s history. Vaziri speaks readily of the empress, whose name he pronounces with two short bursts of air. “FA-rah! She was eh-Woman of the Year. She was very kind to me,” he told me, evoking the creepy intimacy that exists between people who have never properly met.

In 1968, Takhti — the legend — would meet his end in a hotel in downtown Tehran. Though his death was ruled a suicide, thousands of Iranians believed that the shah’s secret police, the SAVAK, had put the chivalrous, if slightly autistic wrestler to sleep for his political activities (he defended the poor). Vaziri went into a deep depression. “I knew I had to leave. If Iran was not good for eh-Takhti, it was not good for me”. He moved to America and got a job with the Minnesota Wrestling Club as an assistant coach. There, he met and married his wife, a blond girl named Carol Jean Peterson who worked at a Ramada Inn. He took the gold at the AAU championship in 1971 (Muhammad Ali gave him the medal) and served as assistant coach to the US Olympic squad. In 1979, after years in the regional leagues, Vaziri made the leap to the World Wrestling Federation (WWF), wrestling as “the Great Hossein Arab.” An Iranian impersonating an Arab dressed as a Turk, he was part pirate, part djinn, all man. The WWF that Vaziri joined was in the midst of reinventing itself under the leadership of Vince McMahon Jr, wrestling’s very own Hugh Hefner. Where professional wrestling had generally involved a patchwork affair of small-time regional clubs, each with its own stars and champions, McMahon imagined wrestling as a form of “sports entertainment,” with a nationwide audience. The typical WWF story line was not unlike a soap opera with its share of jealousies, domestic abuse, and torturously elaborate yet clumsily choreographed narratives. Through its scripted performances, professional wrestling evoked the circus, the variety show, and the high-camp musical at once.

There was a pleasing consistency to these storylines, as if the use of an imagination would be superfluous or even threatening to their inner workings. In these narratives, the “faces” (good guys) inevitably confronted the “heels” (bad guys) in bouts that would continue literally and figuratively outside the rubber ropes. Heels, whose ranks included the Undertaker and the Mongolian Butcher, were choleric, hirsute, animal-like. They threw chairs, they wielded knives with abandon, they often traveled with henchmen, they cheated. Faces, or babyfaces — Andre the Giant, Sting, Hulk Hogan— dedicated their victories to their mothers, waved to wheelchair-bound children in the crowd, and always insisted on playing by the rules. Some storylines went on for the length of a match. Most went on, like the best soap operas, for years, occasionally for decades. The faces always won in the end.

By the early 80s, with the advent of cable and pay-per-view, wrestling had become one of the top-rated shows on television in America. McMahon’s primary contribution to sports entertainment was undoubtedly WrestleMania, a pay-per-view extravaganza that was and is the Super Bowl of wrestling (now in its twentieth year, it continues to attract millions of viewers around the country).

Enter the Iron Sheik, the wrestler fans loved to loathe. Iran, with a scowl-faced ayatollah at its head after the 1979 revolution and with American hostages in its grip for 444 days, had become the locus of a new form of fear-mongering and hysteria in Ronald Reagan’s America. He bore Khomeini’s face on his paraphernalia, occasionally muttered a few words of incomprehensible Farsi along with resounding calls of “Ya Abolfazl! Ya Hossein!” before a match, and brought traditional Persian wrestling batons along with him, challenging his opponents to an unfamiliar show of acrobatic strength by swinging them over his head. (Few took him up on it.) In the anti-elliptical lexicon of wrestling terms, this was Vaziri’s “gimmick”.

School children around the country rooted for the Sheik to lose, while the goths and malcontents cheered him on. Of course, the Sheik was only the latest product of a marketing machine that had been generating heels and faces for decades. Just as every superhero has his nemesis, every babyface has his heel. The Iron Sheik was blessed to play heel to one of the defining faces of the 1980s, “Hollywood” Hulk Hogan. In their encounter, the old formula came to life under a spangle of neon lights and before an audience of heavily intoxicated white men: an American hero, defending all that was good, decent, and free against a defiant minion of the ayatollah.

The rivalry between Hulk Hogan and the Sheik is undoubtedly one of the most epic stories in wrestling history. Hogan, who was snatched up by WWF’s McMahon after making his acting debut in Rocky III, would defeat the Sheik a mere four weeks after the Iranian took the championship from Backlund. In their epochal 1984 match, the Hulk lifted the Sheik up in the air by his chin, spat on him and executed the “Boston crab,” which involves sitting on your opponent’s ass while forcing his legs toward his head. Though the Sheik was stripped of his belt that night, it went down as an honorable loss. Later, it was revealed that Verne Gagne, Vaziri’s former coach, had offered him $100,000 to break Hulk Hogan’s leg. The Sheik refused. “I am Shia Muslim,” he explained, when I asked him about the incident.

Over the following years, the Sheik would do battle with Sgt Slaughter, an American patriot who eventually had a GI Joe character named after him. He also teamed up with Nikolai Volkoff, whose gimmick entailed singing the Soviet national anthem. (The duo won the World Tag Team Championship in 1985.) Perhaps it makes perfect sense that WWF wrestling came of age during the 80s. It was a wondrous time: actors became presidents; Michael Jackson changed colors; Tom Hanks became famous for dressing up like a woman on TV. Only in this weird new world could an Iranian become a “sheik.” He went to coke parties with Cyndi Lauper and Mr T and starred in a Toyota commercial. And he, too, was immortalized as an action figure, his likeness stamped in plastic — a tiny mass-produced monument to wrestling greatness.

One day in May of 1987 on the New Jersey Turnpike, the bubble burst. In town for a wrestling event and fresh from the Newark airport, the Iron Sheik was pulled over by state police with fellow wrestler “Hacksaw” Jim Duggan — his most recent enemy. Face or no, Duggan was drunk and had weed on him. The Sheik was high on cocaine, with more stashed in his suitcase. The scandal shook the wrestling world: sworn enemies in the ring were not just caught together, but caught getting fucked up together. Duggan was let off with a warning, and the Sheik received a one-year probation. “In the New Jersey, you cannot drink and drive,” he reflected when he told me the story.

It went downhill from there. Vaziri left the WWF in 1988 and reappeared only in 1991, just as the first Gulf War was brewing. Like the hostage crisis, the war provided a narrative that could propel him into the limelight. It also provided him with a new identity: the Iraqi Colonel Mustafa. The Colonel was allied with General Adnan, an (actual) Iraqi wrestler, as well as with Sgt Slaughter, who in the intervening years had turned heel and become a Saddam sympathizer. Hulk, in the meantime, toured US military bases as the bombing began, draping himself in the American flag with every victory. But the Mustafa gig couldn’t outlast the war itself. The Sheik made one final appearance on the scene in 1997 as co-manager of a wrestler called the Sultan, but it was clear the glory days had passed.

Wrestling, too, was suffering. There were allegations of steroid abuse, sexual abuse, corruption. Wrestlers were dropping dead before the age of 50 — from car accidents, suicides, drug overdoses, heart ailments. When television ratings started to dip in the early 1990s, the sport had to reinvent itself to keep people coming back for more. There were declarations of a “new generation.” There was more sex, more scandal. Traditional babyfaces like Hulk Hogan turned heel in what was referred to as the “attitude era.” When in 2000, the World Wildlife Federation forced the WWF to change its name, it truly marked the end of an era. To old-school fans, World Wrestling Entertainment had surrendered to crass, crude commercial values. That same year, the Sheik sold his pointy wrestling shoes on eBay for a hundred dollars.

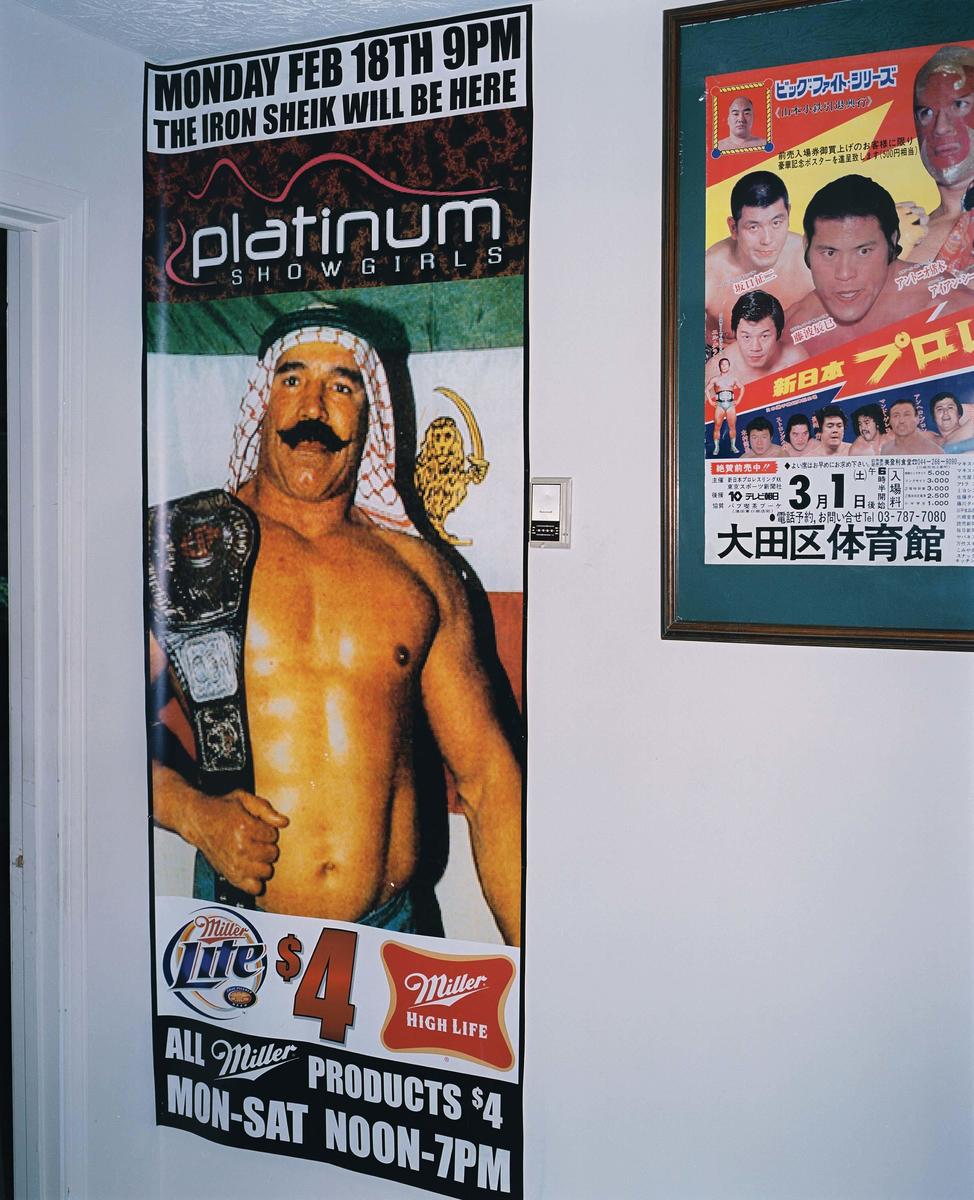

I met the Sheik in Fayetteville, a sleepy suburb of Atlanta, after calling 411 for his number. My initial phone calls were met with a confused rumble, and then deferral. “Call back tomorrow, it is better,” as if he had a terribly tight schedule. Most days the line was busy, sometimes even disconnected. Eventually, I arranged to visit him, driving up to a small apartment, half of a simple one-story house with a leaky ceiling, wall-to-wall carpets, and all the ambience of a Motel 6. Everything was brown. In the living room sat the Sheik, supine in his throne, a plump rocking couch that was the sole piece of furniture capable of accommodating his size. The room was sparse, with a mat depicting the Grand Mosque in Mecca (he is a haji, having gone to Mecca as a child), two creased WWF posters bearing his oiled physique, an Iron Sheik action figure, and a small, simple factory-made “Persian” rug. The Sheik was not above asking strangers for help. Over the course of the day we spent together, he asked me for money no less than three times. “Something small, Baba. Anything from my countrywoman?” (When I told him that I, too, am from Iran, he would not stop calling me his “countrywoman,” which was mostly endearing, until I began to worry it might be interpreted as the mistress from the country house.) “Please Baba? I love you forever.”

Also at the Sheik’s Fayetteville apartment was Eric Simms, who has worked as the Sheik’s manager and booking agent since 1988. They make for an odd couple. Simms, a pale, big-eyed native of New Jersey in his forties with a Sopranos accent, started out as a wrestling fan, eventually hanging out with the wrestlers after hours and booking gigs on the side. The Sheik ordered Eric around, plainly enjoying the idea of having someone who “manages” his affairs. “Eric Baba, get me the belt. Eric Baba, let’s have a drink.” For the most part, Eric ignored him. “My job is to make the Sheik shine,” Simms rapped. One does not doubt that he is skilled in the art of bullshit. The Sheik turned, smiling, “You see he is a Jew, Baba, and I am a Persian. I am open-minded guy.” Eric was Jew Baba. I was Country Baba. Khomeini was Ayatollah Baba. Everyone the Sheik deems okay enough is a Baba.

Over the years, Eric and the Sheik have seen the worst of times together. At times, their script seems to borrow liberally from that of Cops. There have been legal problems, various shades of bankruptcy, accusations of alcoholism and drug abuse, a car accident that left the Sheik with an artificial knee. And there have been tragedies of a different order, as well. In 2003, the Sheik’s daughter was murdered by her boyfriend. And earlier this year his wife of almost forty years left him. Sometimes he blames her for his present difficulties with money. He subsists on a $725 check from Social Security every month, which he supplements by signing autographs at area high schools (when the school board approves), sports bars, and Wal-Marts; quickie appearances on the radio; and even, yes, The Jerry Springer Show (for which he received $500 and a limousine ride). “I can take him anywhere, restaurants, clubs, everywhere. His personality, his charisma, you can’t go anywhere without someone recognizing him,” Simms told me.

In 2007, a producer from the Howard Stern show heard him on a small-time radio station and invited him to be a participant in the program’s Killers of Comedy tour. In the show, he plays himself. He wheezes, grunts, explodes into Tourettic fits — insulting Jews, homosexuals, blacks, Hulk Hogan, whomever. (He has been temporarily suspended from the show for insulting Beetlejuice, a dwarfish actor with an unusually small head, but seems confident that he will be reinstated.)

Type “Iron Sheik” into YouTube and you will find a world of videos, all wincingly adolescent and more or less a variation of the same three themes:

Iron Sheik smoking crack 2007.

Iron Sheik’s views on Jews.

Iron Sheik talks about having sex with Hulk Hogan’s family.

Some have been viewed by nearly a million people.

In one video, the Sheik gets increasingly intoxicated and ejects a steady flow of verbal flotsam:

You fucken piece of shet…

You suck Hulk Hogan ass, you suck Hulk

Hogan deck…

“The videos help us get the Sheik gigs,” Simms told me.

The Sheik’s other daughter lives about five miles away. Along with Eddie the driver, who was still too stoned to drive, we made the short trip to a gated community of Lego-like ranch homes. “Say hello to Baba Sheik!” He was very excited to see his two tiny granddaughters, each with very thick, very Iranian eyebrows — a genetic gift from their Baba Sheik. One room in his daughter’s home serves as an archive of Sheik ephemera. There are stacks of old wrestling magazines, trophies, medals, pictures with Cyndi Lauper. It was here, with his family and most intimate possessions, that I thought I might get a glimpse of Hossein Vaziri, the man. I tasked him with a series of hopefully pointed questions.

I asked him about the greatest day of his life: “December 26 1983, the day I take the WWF title in the Madison Square Garden.”

about his favorite place:

“The Madison Square Garden in the New York.”

about his father:

“He was very strong man.”

about the Iranian Revolution:

“That was the hardest thing in the eh-Persia.”

about Ayatollah Khomeini:

“Some people think he was good for Iran, some not.”

about Mahmoud Ahmadinejad:

“Some people like him, some not.”

Switching from English to Farsi, his native tongue, didn’t help; he delivered the same truisms in both languages. There was no “offstage,” no knowing smile, no moment of candor. Worryingly, it seemed as though there was little beyond the gimmick.

Gazing at his WWF title belt hanging on the wall — a copy, mind you — he seemed intensely sad for one moment, his brows furrowed into a crooked V. All of it came together — the exile from Iran, the foiled Olympic dreams, the short-lived WWF title, the days of wandering the country doing gigs at Sizzlers and gnawing away at a schtick that went stale long ago, the bitter knowledge that Hulk Hogan had his own reality TV show and he didn’t.

My heart went out to him. I suggested a drink, and it was like the world had been born anew. A smile! A massive one! In a world of unlimited possibilities, the Sheik is a simple man with simple wishes: “I love to have eh-drink.”

Later that evening, after veering off the highway to buy vodka coolers (no cups!) en route to the awards ceremony, we spoke about how wrestling had changed. The WWE was riding high again, blanketing airwaves with a range of programs, from WrestleMania to Raw to SmackDown. But the new generation had strayed from the noble intent of the elders, he told me. This new wrestling was flashier, higher tech, less sincere. “Less psychological,” he said. The Sheik’s story, his bittersweet descent from meteoric success, seemed a distinctly American one. Hossein Vaziri had engaged in this mysterious thing called “show business,” had seen the top, had been inducted into a Hall of Fame or two. “I born in Iran, but I be in Madison Square Garden. For me, America was good.”