New York

Welcome

Kashya Hildebrand Gallery

March 3–April 16, 2005

He’s produced living rooms in solid gold, packaged veils for sale “as seen on TV,” and brought the imaginary spoils of the US-Iraq war to a Chelsea gallery. Artist Farhad Moshiri has now turned his hand to curating, here taking on the notion of the “ethnic artist.” Glitzy, tawdry, and highly relevant, the show poses critical questions through an ambitious claim to have “turned the art market on its head.”

The work on view is largely coherent, original, and visually compelling; it is also wholeheartedly spectacular and unashamedly seductive. The eight artists in the show demonstrate a range of approaches to themes, materials, and representations from Iran’s popular culture. The gallery entrance frames a pair of cowboy boots and a biker jacket straight from a Wild West flick set in ancient Persia: Designers/artists Michael and Hushi have created a wearable collage that recycles both Tehran and Las Vegas. From the opening line, Welcome is a play with the cowboys and Indians game of “otherness” in art, via visual strategies that blur distinctions between high and low, East and West.

Moshiri extends his native Iranian hospitality to the viewer, but continuously reminds us that it’s pure spectacle. Sofreh, a collaboration with Shirine Aliabadi, fills the center of the gallery with an imaginary Persian meal; each of the gilt-edged plates is printed with a different iconic image, from actors and athletes to advertising slogans and greeting cards. It’s an apt metaphor for an exhibition that illuminates consumerist ploys, brilliant (and unintended) humor, sentimental urges, and a decorative flamboyance that is by no means exclusive to Iranian society. Moshiri could have strengthened his statement by including artists from other regions, and he is quick to admit being daunted by the practical aspects of such a project.

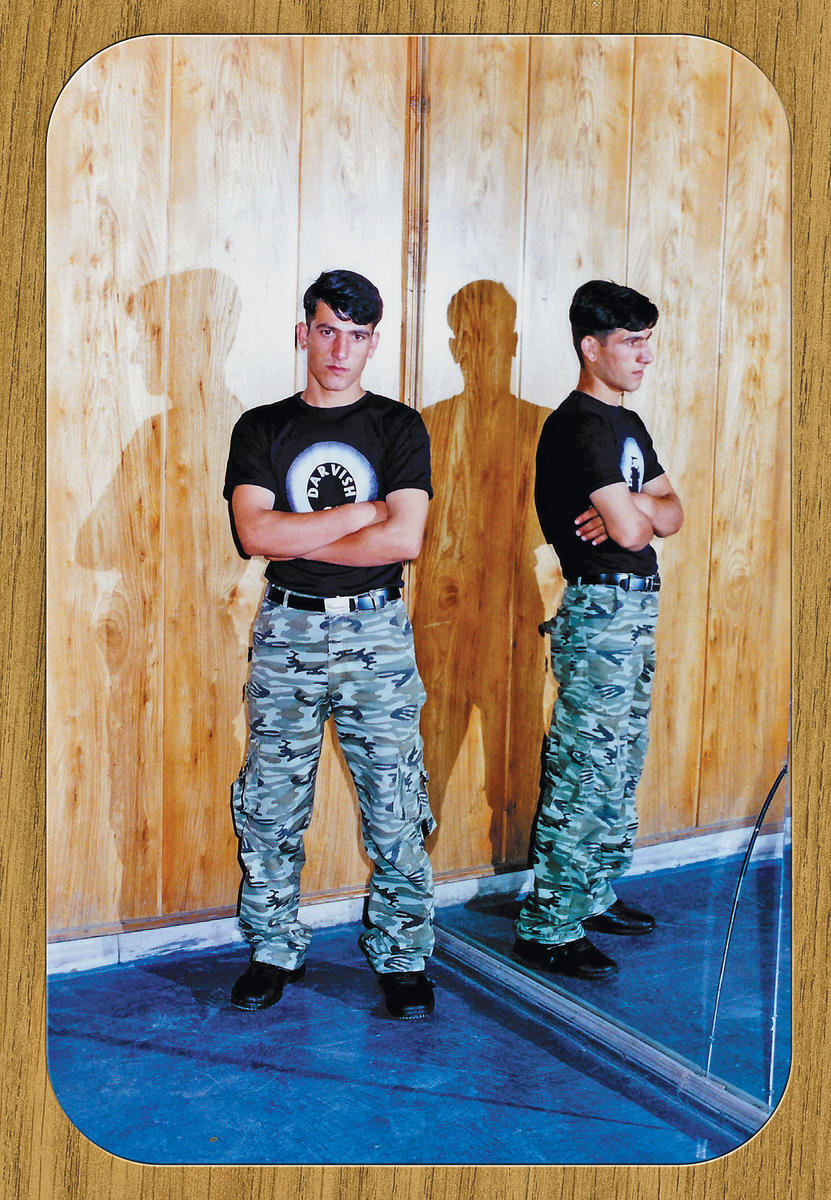

The main attraction of the banquet is Moshiri’s own work, which dominates the exhibition as he plays gleefully with the idea of curatorial license. This may be an advantage — where else would we find avant-garde maverick Fereydoun Ave cheek-by-jowl with a vernacular photographer from Tehran’s Imam Khomeini Square? The grouping is unexpected but not that arbitrary: Ave’s collages of wrestlers, roses and Cy Twombly–esque splashes of paint reference the same local notions of heroism and masculinity as the poignant studio portraits of Bahram Afandizadeh and Mehdi Hosseinzadeh.

But while the contemporary stylistic devices of Ave, Moshiri, or Aliabadi put the “kitschy” appeal of the work in quotation marks, local craftsmen/artists Afandizadeh and Hosseinzadeh are practicing their craft in earnest. Placing them in the same show runs the risk of presenting the latter artists as naïve and their work as only valuable in terms of kitsch. And what is a celebration of “Orientalist kitsch” but a compounding of western condescension towards “other” cultures? Negar Azimi’s catalogue essay makes an important point in referencing the local meanings and histories that vernacular photography represents, but she too recognizes the pitfalls: “Where does his craft end and your Art begin?”

The art world is often quick to neglect local histories, and playing cheeky with Orientalism has its dangers. How obvious must a critique be, and can it play the game without complicating the issues? Moshiri has considered the consequences of taking sides: In an interview with the editor-in-chief of Bidoun included in the catalogue, he demands an answer to “the valid criticism of perpetuating cultural clustering.” His own answer, it seems, is provided a few pages back in Tirdad Zolghadr’s contribution to the catalogue. “Strategic essentialism,” Zolghadr believes, “remains the most efficient key to penetrating the Center of the Real.” Luckily, Moshiri’s show is more communicative than Zolghadr’s essays are accessible. It appears that the authors believe in addressing the center-periphery problem from within the art market, following the tendencies of “contemporary” or “internationalist” art in order to subvert its models of supply and demand.

Michael and Hushi’s cowboy boots, then, are a highly appropriate symbol of challenging the western art world from within. The western tradition of staging so-called primitive cultures has a long history; a need for defining the other that has doubtless evolved since the days of parading “authentic” Sioux Indians at the World’s Fair, but continues as a staged phenomenon of exotic display. The questions that Moshiri raises are important ones, but remain unanswered, localized and slightly glossed over by the sheer spectacle. It should not however, be overlooked that Welcome is a valuable experiment in testing the boundaries of “selling” and “exhibiting,” “kitsch” and “art,” “self” and “other” — concepts I gingerly place in quotations, for as the exhibition demonstrates, they are by no means mutually exclusive.