Jace Clayton and Kelefa Sanneh have lived faintly parallel lives. Both grew up in New England as children of mixed marriages. Both went to Harvard College, where they each found a welcoming niche in Boston’s various musical scenes. Both have made careers out of their love of music — Clayton as a world-renowned DJ, producer, and blogger, Sanneh as a music critic for The New York Times and now as staff for The New Yorker. And both of them owe it all to noise.

Noise can refer to all kinds of sounds, of course. Often it describes something jarring or disagreeable, nonsensical or annoying. Improbably, a musical genre emerged in the 1980s that called itself “noise music.” Almost inevitably, that genre ended up in Japan, where it sprouted what was either a subgenre or the end of the genre, depending on whom you talk to: Japanese noise.

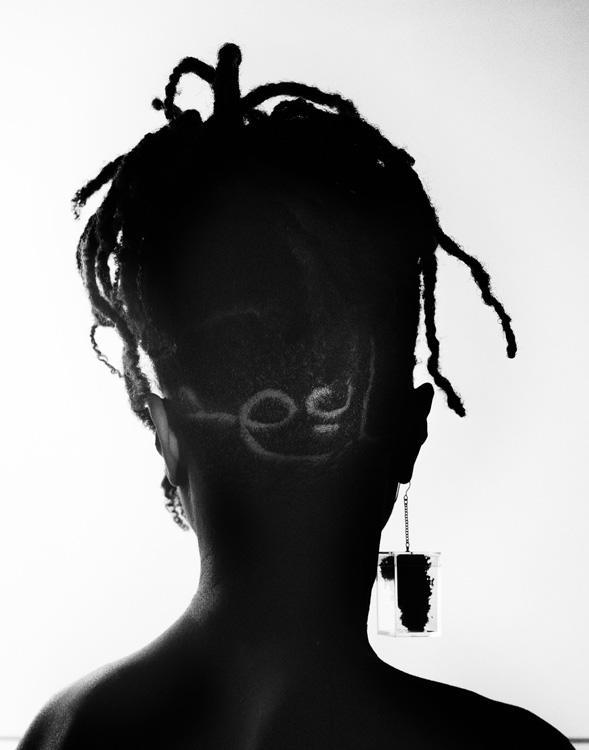

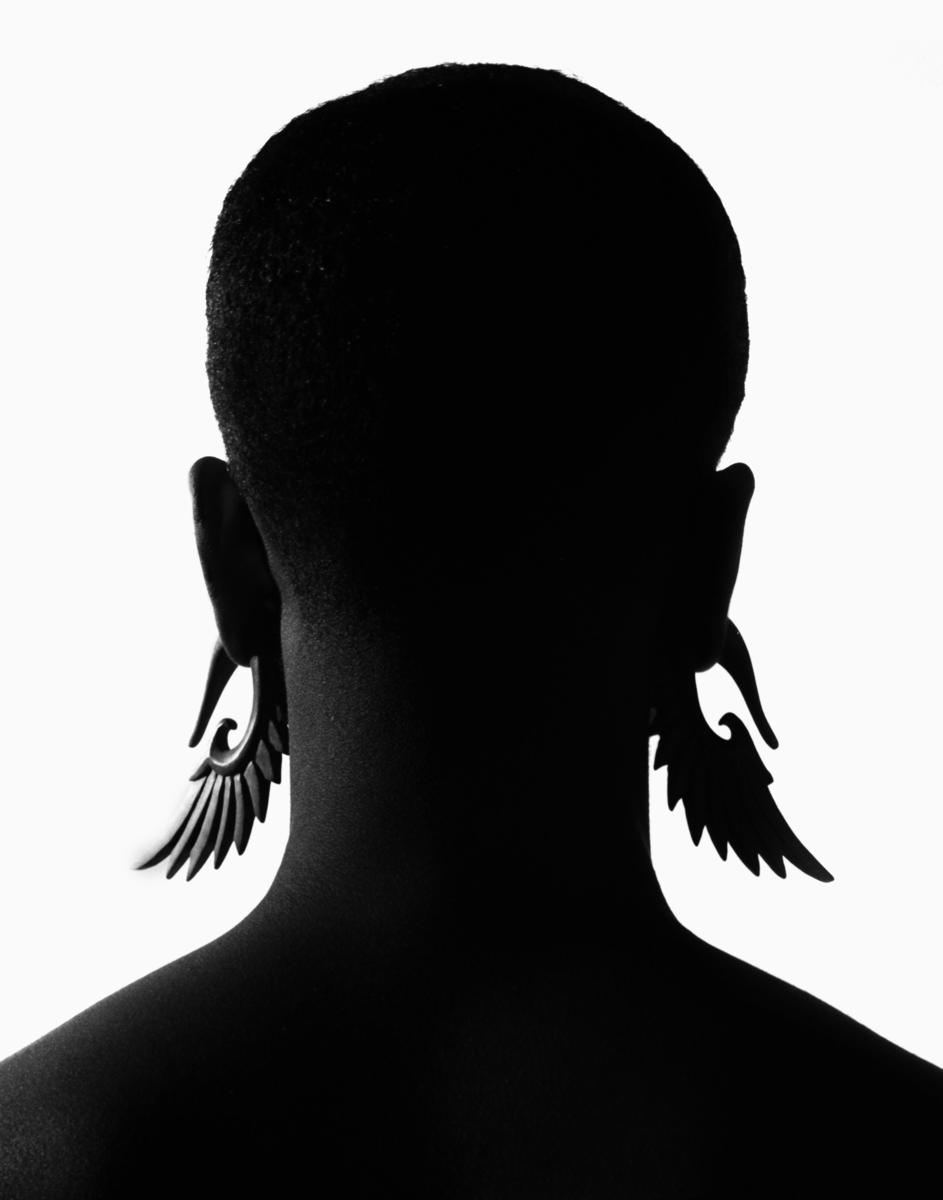

In what follows, Sanneh, also known as K, and Clayton, aka DJ /rupture — two of the most distinctive and articulate voices in contemporary music criticism — discuss their own musical trajectories into and out of noise music, while giving us a glimpse of what a John Hughes film might have been like if it had featured nerdy black kids from the suburbs.

Kelefa Sanneh: What was it that drew you to noise music? Was it a structural thing or more of a sensual thing? Like, “Oh, I love the way this sounds” or more “This sounds fucked and everything I know sounds not this fucked”?

Jace Clayton: It was sort of sensual in the broadest sense, I guess. I remember being physically shocked by the very first track on my first noise cassette.

Michael Vazquez: Which was?

JC: It was by Hanatarash. The cassette was Eat Shit Noise Music, a compilation on RRRecords. It came in the mail; somehow I had gotten one of their catalogs.

MV: RRRecords was like the flagship noise record store in America. But weren’t they pretty close to where you lived?

JC: Close enough. I remember going there to interview RRRon, the guy who ran the store, for my fanzine in high school.

MV: Your fanzine?

JC: It was great! We did two or three issues, like Xerox, hit-and-run style. It was called Infusion.

KS: Mine was Ttttttttttt, the unpronounceable fanzine. [Laughter] That’s exactly eleven t’s. There were maybe five issues.

JC: Was it about music?

KS: Yeah, though we were more interested in humor and some stupid highly conceptual comics. I did it with my best friend Matt. He had a recurring feature, a comic strip, called “Bob the Dead Cat.” It was mostly stuff like that, parodies of things. But then also, band interviews with whoever would talk to us.

MV: Like who?

KS: Like, Alice Donut? They were an East Village scum-rock punk band, freakish. And they were on Alternative Tentacles, which was the Dead Kennedys’ label, so to us they were huge. But they didn’t really play New Haven, so we had no idea if they had fans or if they were a band that everyone cared about or no one cared about.

MV: Wasn’t there some primal scene for you, K, when you suddenly discovered punk rock? Maybe you were listening to Ice-T…

KS: It was two things, actually. One was Ice-T, the Iceberg/Freedom of Speech record, because Jello Biafra from the Dead Kennedys did the intro. “‘Attention! America is now under martial law.’”

JC: Oh yeah, that sample…

KS: And then there was the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Mother’s Milk record. I had seen their cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Higher Ground” on MTV — not knowing, of course, it was a cover. And I was like, “This is awesome” — it was loud and energetic and weird and that dude’s got stuffed animals on his pants. So between those two things, Matt was like, “If you like this stuff, you might like punk.” And he gave me a mixtape, I think for my birthday. This was the end of my freshman year. It was a cross section of anything you could get your hands on — the Dead Kennedys and the Dead Milkmen, the Dickies, along with some alternative rock bands. A lot of it wasn’t really punk, it turns out, but for us punk just meant weird or funny or loud. I heard that tape and I was like, “Yeah, I will never listen to the Rolling Stones again.” [Laughter] Not the most prescient thought I’ve ever had, but still. The point was that it was literally an either/or thing. I don’t know if it was that sharp for you, Jace, but for me it was stark. “From now on, I’ll never listen to regular music anymore. I will only listen to weird music.”

JC: Actually, I never listened to regular music. I started off weird.

KS: [Incredulous] You never listened to Michael Jackson?

JC: Never listened to Michael Jackson.

MV: How did you not listen to Michael Jackson?

JC: My mother had this Thriller aerobics record, and I remember hearing that over and over again. But beyond that…

KS: Weren’t your friends all listening to it?

JC: It never sunk in. The thing is, I wasn’t even interested in music. My parents weren’t really music people, so I never got interested in their records or rebelled against them or anything. There just wasn’t much music in our house.

KS: It’s funny, this stuff is so social, you know? Some of the first music I ever liked was Run-DMC. Which, in concrete terms, was a lot more radical than most of the ostensibly weird stuff I was into. You hear that now and it’s like, “Wow, there’s no music there at all. They took out all the music from this music.” It was just a beat and two guys shouting at you. [Laughter] But Run-DMC was the music of all the regular kids at school. It did not seem weird at the time.

MV: Did you keep listening to rap?

KS: Sure. I watched MTV as much as I could back then — we’d just gotten cable— and this was 1990, when Yo! MTV Raps was on. NWA videos were on all the time; a few years later Snoop Dogg hit. So I saw all those videos. But that show 120 Minutes was a bigger deal for us, because it was the only way to see the videos for any of those alternative bands we were getting into. The thing is, that stuff was presented as alternative. It felt really different from Yo! MTV Raps, which was presented as, if not mainstream, as aspiring to join the mainstream. It never occurred to me that rap was more alternative than the alternative.

MV: How did you find out about stuff, Jace?

KS: Radio. North Andover is within striking range of the Boston radio stations, so we got tons of college stations. And once I started getting into weird music, it was like I’d hit the jackpot.

KS: See, we didn’t have any radio in Connecticut. Matt and I had a rule where we couldn’t both buy the same album. One person bought it, the other taped it. In this way we could maximize our musical universe. And we were buying stuff mainly based on the label. Somehow we’d figured out that that Jello Biafra from the Dead Kennedys ran a label called Alternative Tentacles, so we bought everything on Alternative Tentacles. Fugazi was on Dischord, so we had everything on Dischord. And then somehow we got into that label Shimmy Disc. That was how we ended up buying the Soul Discharge LP by the Boredoms and John Zorn’s Naked City LP. And we were like, “Oh. Oh! What’s all this?” [Laughter] Because besides humor, the most important thing to us was weirdness. When we heard that band Half Japanese for the first time? Music where you couldn’t quite tell the mental state of the people making it? That childlike shouting over horrible noise? We were like, “Perfect.” [Laughter] Actually, that Boredoms album was just probably my favorite album. It’s where my high school yearbook quote came from, me trying to transcribe a little bit of Soul Discharge…

MV: What was the quote?

KS: I have no idea! It’s like a bunch of gibberish. I don’t know Japanese…

MV: So, do you have an idea about why you guys found yourselves questing after horrible noise made by very possibly insane people?

KS: Sure! I mean, for me this stuff was always kind of structural. Its appeal was precisely that it defined itself in opposition to the mainstream. Which is to say, it presupposed that you had an opinion about music. That was such a novel idea for me! When I was listening to the Beatles blue tape or the Beatles red tape, it didn’t seem like they were asking my opinion about what they were doing. But when the Dead Kennedys did “MTV — Get Off the Air,” they’re presupposing that you have opinions about MTV and the kind of music MTV played. And even if those opinions are dumb, the fact of it was an exciting thing. The appeal was kind of unmusical, actually. It wasn’t like, “Oh, those guitars sound like I’ve always wanted guitars to sound.” It wasn’t songwriting. It wasn’t even like, “Oh, this music makes me sad or makes me weep or helps me channel my anger.” It wasn’t any of that at all. It was just — this stuff is far from what’s regular. And once we started to hear more abstract, noisy stuff, it was inevitable that we would try to find out how far you can get from what’s regular. What is the craziest shit ever?

MV: The noise arms race.

KS: So we got one of those Dry Lungs compilations and there was some truly weird Japanese stuff on there. And what we began to realize was that there were these people in Japan that were making, not only the craziest music we’d ever heard, but in some really pure mathematical sense — that they were getting close, in a kind of asymptotical kind of a way, to the weirdest music it was possible to make. Which would be noise! And which would be, totally formless noise. Now of course, once you get to that point, once you start listening to noise music, it’s like you’ve entered a slightly different galaxy. The rules of music start inverting themselves. For one thing, it turns out that the noisiest noise is the one that has all these violent events in it — which is to say, the one that’s actually the farthest away from white noise, which sounds kind of peaceful. [Laughter] So we were like, “The less noisy noise is, the noisier it is?” For example. Or, equally, if you’re in this zone, this world of noise music, and noise music exists in part to fuck with listeners, and fuck with what listeners think music can be, then the only way to fuck with noise music listeners is to rebel against that. So like, The Gerogerigegege puts out “White Christmas White Sperm,” which is just someone singing “I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas” and the sound of a guy jacking off. And the fact that it’s a song, and a pop song, and a very well known pop song, is like the most fucked thing you could do in that circumstance. And there’s that single — remember that Gerogerigegege single, I think it was a bootleg? We weren’t even sure if the band knew about it. It was just two pop songs, two Japanese pop songs, one on each side. But in the context of noise music, that was like, the noise music of noise music. Some sort of weird black-hole physics applies. [Laughs]

MV: And you executed this maneuver in high school, still?

KS: Oh, this was all high school. I mean, I still loved it in college, but my love of, like, those Japanese bands really peaked in high school.

MV: Was it high school for you too, Jace?

JC: Yeah, definitely.

KS: Did you know anyone who liked it?

JC: No! I really didn’t. It was like you were an individual dot in a constellation of listeners out there somewhere. For me it was all RRRecords mail order. Send them a check one day, get back a few cassettes two days late. Those compilation cassettes were the cheapest way to get ahold of things. I wasn’t a completist or anything — even then, at the height of my love for that stuff, I realized I wasn’t going to need, like, six records by Incapacitants. Just, you know, two of them. Laughter]

MV: Was your interest in noise as Japanocentric as K’s?

JC: Completely! I didn’t hear anything like the same level of noise anywhere else. And I was not really interested in punk weirdness or hardcore weirdness. But I did love the absurdist spirit of the Japanese stuff, as well as the sound of it. There was that Hanatarash record, William Bennett Has No Dick. And the whole ridiculous, “We don’t know English but we’re putting a collection of preschool potty words together.” The packaging, too, was often pretty tongue-in-cheek. But at the same time, there was someone like Merzbow, who was even then pretty… single-minded.

MV: Were either of you into Boyd Rice and NON or any of the British stuff? It’s interesting to me that for both of you the entrée to this world of noise music is specifically Japanese. Or did Boyd Rice have no sense of humor or something?

KS: Having no sense of humor was not the problem. Masonna was really, really funny… The Gerogerigegege was hilarious… Merzbow — not funny at all. Same with that John Zorn/Naked City stuff. It was… sort of funny? But there’s something about that stuff that is deeply unfunny. Not only deeply unfunny, but it kind of touched on that stuff that I was just like not interested in, all the like, bondage, Asian porn, violence against women.

MV: Which was a lot of the aesthetic.

KS: I understood it in an abstract sense as being fucked up. But it always seemed sort of goofy to me. And insofar as it was an actual fetish for a lot of those dudes, it never seemed hot to me. But Boyd Rice… I don’t think I ever heard that stuff back then. I missed all the British stuff. Maybe those records were too hard to come by? Or [laughs] it might not have been noisy enough…

MV: Sure. A lot of say, Throbbing Gristle, is not so extreme, despite its name…

KS: Exactly. I mean, if you heard a compilation track from, like, Masonna, and you managed to listen to one of their records in the store… you’d be like, “This sounds like the fucking world is ending. I’m buying this.” But with a group like Throbbing Gristle, the records you could get your hands on — we were like, “This is synthpop or new wave or something.” At a time when you couldn’t sample stuff on the Internet and there was no other way to find out, that would be enough to turn you off right there. Learning about a band was expensive. You were like, “Do I want to waste twenty bucks finding out whether I like Throbbing Gristle? Hell no! ’Cause I heard they might be synthpop.”

JC: Yep. I had that exact experience.

KS: And like, that feeling? Of literally being in the record store and seeing the CD in its wrapper or the cassette or whatever — and having to part with money in order to find out what it sounds like?

JC: Yep.

KS: It definitely helped inspire a certain kind of tribalism. It made you want to be like, “Oh, I’ll stick to this record label. Or I’ll stick to this scene. It’s Japanese noise music — you’re guaranteed it’s going to be screwed up.” Even a band like Ruins that was a little more musical, you were still guaranteed it was going to be crazy. And that the mythology behind it was going to be crazy. Like, you heard a rumor that the Hanatarash dude drove a bulldozer through a club. [Laughter] And you know, it’s not like there’s a book on Hanatarash. Or there wasn’t then. There’s no way to check this stuff. So then when I listen to their records, that’s what I’m going to be thinking about.

MV: Did Matt get into all the Japanese stuff, too?

KS: Yeah. It was three of us, actually — me, my best friend, and my girlfriend.

JC: Wow.

MV: I take it your girlfriend was not into noise music, Jace? [Laughter]

KS: But yeah, a lot of the stuff that’s connected to noise music, or a lot of the ways in which other people were approaching it, I didn’t figure out about until later. You’re right, though, that a lot of that stuff is really not funny. Maybe it’s that when you listen to noise music you can kind of supply your own funny. You know, you’re in your room in Connecticut listening to Merzbow for an hour. That is such a deeply weird thing to do. Maybe funny is almost unnecessary at that point.

MV: Or maybe Boyd Rice is secretly really funny. Not long ago I saw these vintage films of Viennese Actionists in their heyday — sixties and seventies — engaged in legendarily “controversial events,” with the blood or animal parts or the sex or what-have-you. But the thrilling part for me, watching them now, was less the outrageousness or transgressiveness of their actions than the sense that they were having a ball.

KS: Sure. I guess… in retrospect there are all these contradictions. Not least the fact that when I was most into noise I was still listening to all this idealistic left-wing punk music. I had Dead Kennedys lyrics on my wall, I had all these political buttons on my jacket. I remember going to a big gay rights march in DC. I sort of took it for granted that noise music was political in that same kind of warmed-over New Left kind of way. Whereas, in fact, a lot of that noise stuff was either pseudo anti-left or nihilistic, same as that Boyd Rice stuff. Even some of the people in the noise scene seemed to be sort of right-wing. But I guess the important thing at the time was that it seemed so opposed to the mainstream, whether it was idealistic or not.

MV: In a way, the industrial scene seemed more right-wing, while the noise scene seemed more… amorphously anarchic. The noise thing didn’t have the same fascination with order and emblems of authority. There was definitely a romance of authority with the industrial scene. Even if it was supposed to be a deconstruction of it.

KS: Sure. I mean the industrial scene lived partly at that point where like, military culture and gay culture collided. [Laughter] You know, shaved heads and combat boots, this sexualized, quasi-military thing… which is kind of a right-wing, fascist phenomenon, but in a gay context means something totally different. And similarly the music had one foot in something really harsh and German sounding and another in something really clubby. But maybe it was just the times. This was when Nine Inch Nails and Ministry were emerging as commercial forces, and it just seemed obvious to me that this was glorified MTV music. So yeah, I didn’t interact with that stuff at all.

MV: But you did get into industrial stuff, right, Jace?

JC: At about the same time as the noise stuff, actually. And in the same way, through the radio.

MV: You had a sort of “great books” of weird music at your fingertips.

JC: Yeah! What was great, too, was that college DJs would sometimes play a song and then tell you a little bit about it. So I was like, “Okay, Belgian techno.” Then I would go to Harvard Square and the record stores and buy CDs.

MV: Had you always been a big radio listener?

JC: No, but my sister was, and when I started getting into music, in middle school, it was through her. She was a big fan of the main commercial alternative station, WFNX. That’s how I’d heard the Sugarcubes, which was the first band I ever got into. And then one day they played a song by this British band called Stump. And on this song, they had sampled frogs! There were all these timbre-ly, texturally weird elements in it. So then I went out and got myself a Stump tape.

MV: A Fierce Pancake, or the earlier one? Was it that song that goes “Charlton Heston Put His Vest On”?

JC: It was deeply weird. Stump wasn’t the kind of band they would normally play on FNX, but the band had broken up that day, so they made an exception.

KS: But then when you first heard actual noise music, did you feel like that was the end? That was the logical conclusion? Or was that just one more weird sound in a universe of sound?

JC: It definitely felt like an end. But also, really, a beginning. I had gotten that first noise cassette because it had Ruins on it — and Ruins, as you were saying, are still quite musical, if ridiculous and operatic and overwrought. But with Hanatarash, I was like, “What is this?” It felt like some sort of document of physical violence. That was the ripping open of possibilities right there. For me the idea of noise music is about violence against structure. It was literally audible in Hanatarash and more suggested in other stuff.

KS: Part of what is so confounding here is that the violence against structure, the violence itself, becomes a kind of structure. Hanatarash is violent, for sure, but it’s also recognizable as a genre. You can tell that it’s not some composer at Mills College who might approach noise from a totally different place but still be headed toward the same thing. The kind of violence that’s in music like Hanatarash implies all these other things. It implies loudness, for one. Which is obviously a totally nebulous concept, especially nebulous in the case of noise music. Like, what does it mean to make loud noise music? [Laughter] That’s crazy, right? But Hanatarash sounded really loud. Really aggressive.

MV: One of the nice things about noise music is the way that, from time immemorial, people have said, about a thing they don’t like, “Turn down that noise.” And then here was a scene that said, “We are that noise.”

KS: Yeah, but that’s old, too. I remember when I finally got Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, that Lester Bangs essay collection, there was a piece called “The White Noise Supremacists.” I was like, “Yeah, he’s really going to get into that shit.” And then it was all about — punk bands? About goings-on at some Richard Hell and the Voidoids concert. I was like, “That’s not noise, that’s rock music!” It’s like, if anything, the noise-music people were slightly more right than their forebears about what they were doing. [Laughter]

JC: See, for me listening to noise music was more about expanding the possibilities of what could be music. Texture, sounds, amusicality… could be stuck into songs. After noise, I was just kind of more open or appreciative. Part of what I liked about noise in the first place was this sense that, “Wow, all these many, many things are possible.”

KS: But that is the difference between you and me. You’re an artist. You’re like, “These sounds are wonderful.”

MV: But you were in all kinds of bands, K.

KS: Oh, I was in bands all the way along. Not before punk, but before noise, sure. I had always played violin. But then that summer after freshman year, I got a guitar. And I had a… Beatles fake book? And a little Pixies fake book. I learned those chords enough to be able to play stuff. And then we had series of punk or experimental or goofy bands. Our high school had a music studio with, like, two-inch tape reels, too, so we’d do, like, weird tape loops — we’d go down the hall with it, and the tape is looping around the microphone stand and coming back. And we were like, “Wow, we get credit for this?”

MV: Do you remember the names?

KS: [Long pause] At one point, the one with the most loops was called Vladimir McCarthy. But the one we spent the most time on was Tender Vealcalf. That was more of a joke-rock thing.

JC: Very nice.

KS: But — how can I put this? Our music never got good enough to seriously disturb our music listening. It was never like, “Aww man, we’re making music and it sounds great and we’ve figured something out and we’ve got our sound.” It was very not good.

MV: I don’t not believe you, actually.

KS: Not having that temperament that Jace has, we were never like, “Oh, let me create something beautiful with this.” We were like, “Music is ridiculous and hilarious.”

MV: Were you making music in high school, Jace?

JC: Yeah. I was using a four-track. My parents had a video camera, so I would record and sample with the video camera, then dub that to the four-track. It was very rudimentary. Though, actually, I made one of the best sounds I ever created then. I was doing super-primitive stuff on my computer, a Commodore 64, which had this amazing sound card. Sometimes the computer would crash and somehow corrupt the audio file I was working with, and it would, like, glitch. And I was like, “Whoa! This is great.”

MV: And in college?

JC: Not really. In college I did a little sound design. And I started DJing…

MV: How did that happen?

JC: Well, first I had a radio show. Pretty free-form. On the graveyard shift at the MIT station. And then it was, hearing jungle music — dancing to the hour of jungle and drum and bass that they would play at house parties at The Loft. That focused my ambition.

KS: How did you get there? I mean, coming out of noise music, how or why was it that you gravitated toward the beat-oriented stuff, electronic stuff?

JC: I mean, coming out of noise, my interest was just… sounds, strange sounds, nonstandard sounds. And at that time there was all sorts of really weird techno and electronic and even industrial stuff happening.

KS: But I guess I just mean, there’s a certain… It’s what you were talking about, Mike. There’s this supreme entropy and anarchic spirit, and then to have that harnessed to this very neat, meticulously arranged rhythmic music, which in some sense is totally related — but also kind of opposite. So why did you get into that instead of getting into, say, improvisational music, or free jazz?

JC: Ugh! I guess I didn’t see it that way. I’ve never really been interested in improvisation. To me those musics have always been about… materials exhaustion? You know, like, “I’ve got this horn. People have been using this horn for decades and decades. How can I make this sound new?” As a social activity it’s very introverted — almost elitist by default. Whereas, you know, I loved to go out dancing. I loved the anarchic spirit of noise, and the sonic surprise of it, and then for me to hear edgy or unusual sounds in the context of dance music — was fantastic. You know, there are people out there whose ears turn off when they hear a 4/4 beat. They’re, “Oh, it’s techno, it’s machine music, it’s just computers.” But for those who like it, they understand the beat as almost like the minimal structure you need in order to anchor other explorations — of sound and melody, emotional states, all kinds of stuff. So, yeah, to me, that passage made a whole lot of sense.

MV: What about you, K? When you came down from the mountain, because you needed to breathe or whatever, what did you do and why? Or how did you think about it?

KS: I think for me it was easy because my listening had progressed along this path on account of structure and form. And even as that was happening, even as I was gravitating toward whatever weird noise music, I thought of it all as punk in the loosest, broadest, most ahistorical sense. That was the aesthetic. So having explored the formal part, I wound up at Harvard, in the radio station, and they were like, “We’re gonna teach you the history of music.” So then I got into all this stuff a second time, but historically rather than formally. Having discovered noise music as a rebellion against musical orthodoxy, I did my own version of the orthodoxy, listening to these punk albums from the ’70s that I would have rejected as so much rock music in high school. And getting into modern-day punk, and also hardcore. Getting into stuff that was approaching noise from a whole other direction, bands that were thinking they were making very by-the-book hardcore — very, like, flag-waving, orthodox, just bang the songs out, add some political lyrics, a few chords, and record it however you can… and were, almost by accident, approaching abstract form. [Laughter] But doing it from completely within the orthodoxy of punk and hardcore. I mean, I wasn’t necessarily thinking of it like this at the time. But you know, those noise dudes liked to think of themselves as outside the rules of musical genres. And now I was at this radio station at Harvard that was all about rules.

JC: The worst radio station ever… [Laughter]

KS: And I was like, “This is great!”

JC: That’s when I first met or saw you, actually, K, at the radio station.

KS: Yes, there was a test. To be allowed to spend a semester trying out for the radio station…

JC: By the end of the test, I was just writing satirical, increasingly bitter answers to these ridiculous questions, knowing that I would never, ever get in, thinking, “I hate these people, I hate this music, I hate this station!” About a week later, I found out there was a real college station down the river, where you could play what you wanted, which was where I ended up getting a show.

KS: See, by the end of that test, I was like, “I’m home.” [Laughter] They played a song by Pussy Galore, and I was like, “Really? This is what we’re doing? Fine indeed.” Anyway, at that radio station they kind of treat you like a baby. “This is what happened in the Sixties that is relative to our purposes. Now this is what happened in the Seventies. This is what’s interesting about New Zealand. This is art rock.” Basically I spent years learning the rules. Without thinking about it, I was stumbling toward the idea that if what you’re interested in, in a structural sense, was some sort of transgression or outrage or wrongness… obviously that only exists because there are genres and because there are rules. In retrospect it was important for me to be on the inside of the dogma after having so reflexively thought of myself as an outsider. I’m sure if you had asked me in high school, I would have said, “Oh yeah, I’m totally open-minded, there are no rules in music.” It was helpful to realize that I was not as open-minded as I thought I was.

JC: I think my thing for noise was that, until I heard far-from-center music, I wasn’t really interested in music. I was a nerd reading a lot of books. So once I started hearing things like noise, I was like, “Maybe I should start paying more attention. Maybe I need to dig a little bit more.” And I discovered all these new things, mostly by staying up late at night and listening to the college stations. So that was how I got into techno and ambient and dub reggae. Actually, that’s how I got into Arab music. I just realized there was all this stuff that was outside the mainstream media, beaming at me.

MV: Sorry, did somebody say Arab music?

JC: The gateway drug was Bill Laswell. They played the song “Mantra” on the radio and it was great — you couldn’t tell where it was from, but they announced the name…

KS: Bill Laswell. Especially in that era, you could actually find his records! His distribution was amazing. His stuff was in every store.

JC: It’s funny when I think about it now — I was only listening to bands I could get at Newbury Comics. And stuff I could get secondhand at those record stores in Harvard Square. Like all this weird industrial stuff — they’d have all the CDs! Those people must have sold a lot of records.

KS: I think Bill Laswell put a lot of people onto that tip.

MV: You mean the “ethnic tip”?

KS: My dad always listened to African music when I was growing up. So there was no way for that stuff to seem weird to me.

MV: It was your parents’ music…

KS: Yeah, like…

MV: Like, were you guys listening to a lot of thumb piano? [Laughter]

KS: No, we were not listening to a lot of thumb piano. It was Kora music. Jesus. And Graceland. I mean, part of what’s exciting is just striking out past your parents’ world, listening to music they probably hate. We had lived in Scotland in the late seventies, so they remembered the Sex Pistols. Not in any specific way, they just remembered that they were rather nasty young men. [Laughs] So part of liking music my parents hated was liking American music. It’s funny, the punk stuff was complicated, because it was both a reaction to American decadence and an example of it. [Laughter] Both of those things were important; it was music that you could relate to in some boring sense, but also music that was sort of scary. They sounded like dudes who would beat me up. I didn’t have friends that were punk in the social sense. I didn’t have friends who got high, or sniffed glue, or really even got wasted or squatted or anything. I knew about that world — I’d go down to New York and read The Shadow [Laughter] to figure out what the anarchists were doing in Tompkins Square Park. But I didn’t know any of those dudes. So part of it was the idea that it was kind of exotic. And all the music I’ve liked since has been exotic in one way or another. Of course, beyond a certain point you realize music is inherently exotic. But at the time, for me, the Dead Kennedys were way more exotic than Youssou N’Dour.

JC: Actually, that’s the connection between rave culture and noise culture. Even my first noise cassette, Eat Shit — it was a bootleg! They were all songs that had been swiped without permission by this weird guy in Lowell, who had just dubbed his favorite tracks from his favorite noise stuff and was selling it. Which had a lot to do with house mixtapes floating around. Some DJ is just putting this thing on. It could totally be just one guy with a cassette deck spreading this out.

MV: My idea about you as a producer of cryptopost-dubstep music was that it was actually the Japanese that prepared you for black music. [Laughter]

JC: Wow.

MV: Yep. [Long pause] Okay, so tell me how I’m wrong.

JC: I’ll tell you how you’re wrong. First of all, when I was listening to all this noise music, I was getting really into reggae. Like, starting with the Seventies and the dub stuff and then getting up to speed, I guess? By the time I was in college, it was current dancehall seven-inches. I mean, sure — a lot of people associate me with noisy, post–drum and bass breakcore or whatever. And fair enough. But the mix that brought me to international attention was called Gold Teeth Thief, which started with Missy Elliot. A lot of the scenes where I would be invited to play later on were, like, breakcore underground European squats, where playing Missy Elliot was the noisiest, most unintelligible thing you could possibly do. I would be in Switzerland and people would be like, “What is he doing playing this Top 40 music?” But people sort of latched onto the breakcore aspects.

MV: So jungle and drum and bass was not some kind of racio-epistemological breakthrough.

JC: No. I mean, it was a breakthrough, in that it made me want to become a DJ. What I loved most about jungle was the rhythmic ridiculousness of it. It had all these structures that were hard to interpret at the time… Plus, all these reggae samples, which I knew — music I loved — and hip-hop samples, which I knew less of. It was this amazing idiosyncratic thing, very fast, the bass lines playing at different time-speeds within one song. All that was mind blowing. But then it became really regular, formulaic. And I was like, “This sucks, the music I loved really tanked.”

KS: Was that when the Darkstep thing happened?

JC: I mean, whatever you want to call it. That’s really what prompted me to find my style. I had started out as a DJ playing jungle, but then I suddenly found myself not even wanting to buy those records when they came out. And I had all these other records — for years I had been buying reggae seven-inches and hip-hop twelve-inches and stuff that would be categorized as “world music” and all this experimental stuff. So I started trying to incorporate those records into my jungle sets. Actually the first person I saw mixing jungle and reggae was Mutamassik, an Italian-Egyptian producer and DJ.

MV: With whom you did “The Bidoun Sessions” back when Bidoun was a party crew in Dubai, right?

JC: Yep. I mean, this sort of thing was bubbling around; a bunch of people were playing around with these ideas. But what sort of developed into my style was taking a drum and bass record but then maybe I’d put on an R&B track of a woman singing, or a rapper like Dead Prez. And then mix that with the instrumental flip-side to a new dancehall single. And as I got more technically comfortable with that, playing with various tempos, I just started pulling in more. So if I had a record with Turkish darbuka and clarinet — I couldn’t just play that in a club, but if I mixed it with a hip-hop backbeat, gave it that 808 kick, then I could play it, and people would react to it. And I just got further and further… into doing what I do, I guess. At some point, I brought on a third turntable to try and accommodate these longer blends.

MV: And breakcore?

JC: I mean, it was about that time that I started hearing rumors that there were people doing something called breakcore who were bringing in noise… It was like they were reintroducing the ragga wildness of jungle via a filter of nostalgia for classic noise and distortion. I was like, “Great!” That tapped into my love of industrial music, as well. So I saw DJ Scud play a party in New York and I thought, “This is fantastic! All these pleasure centers being pushed at once.”

KS: It’s funny. For me, in retrospect, breakcore was the end of my interest in noise. Not forever — I could listen to noise all day long these days. But at that point, when the “digital hardcore” stuff happened, I was excited, ’cause it was jungle, but like, punker and more fucked up. But then somehow when the next wave of breakcore happened…

JC: When the genre rules set in?

KS: It wasn’t even about genre rules. By that point, the break was so much more interesting to me than the core? [Laughter] Or something. Anyway the idea that some producers were taking jungle and putting noise on it… actually pissed me off almost to the point of offending me. At this point I was starting to get deeper into dancehall. I remember going to my first dancehall show in Boston. It was Bounty Killa, and it was nineteen minutes long. He might have done four songs? [Laughter] So, it felt like… you know, the meaning of “fucked-up” keeps changing, but at that moment, that was it. Those full-tilt dancehall reggae mixtapes just seemed so insane to me, so harsh and so energetic, that any noise you could add would just slow it down. Drag it back. I think I felt… condescended to? Even with DJ Scud and some of the British stuff, I was like, “You guys don’t have to put noise on this to make me listen to it. It’s already insane.” In a way, my own musical history was implicated. “Oh, you’re one of those dudes that hears reggae and thinks, ‘This is pretty good! It would be better if it sounded like the Boredoms!’” All that stuff kind of helped me boomerang, helped me be able to hear music that was ostentatiously unnoisy. In some cases ostentatiously un-fucked-up. Deeply, almost pathologically normal. [Laughter] Which maybe I wouldn’t have been able to hear. Among lots of people I know now, I’m the one who likes normal music. But that stuff would have been a lot harder for me to hear without noise and without that structural approach…

MV: I do feel, though, K, that there is a red thread of perversion that runs through your entire… career as a listener, if you will.

KS: Sure, but that’s one of those words that’s like… I mean, how long can you spend inside your own head before that word stops meaning anything at all? How long can those oppositions keep going, really? [Laughter] You know? Like, perverse to whom?

JC: I’ve been perverse for a pretty long time.

KS: But there’s got to be something there to be perverted. By the time you’re perverting the socially acceptable love of Hanatarash you’ve gone pretty far through the rabbit hole. I mean… I wouldn’t even know where to start. Would it be more perverse to love Radiohead or hate them? What would that even mean?

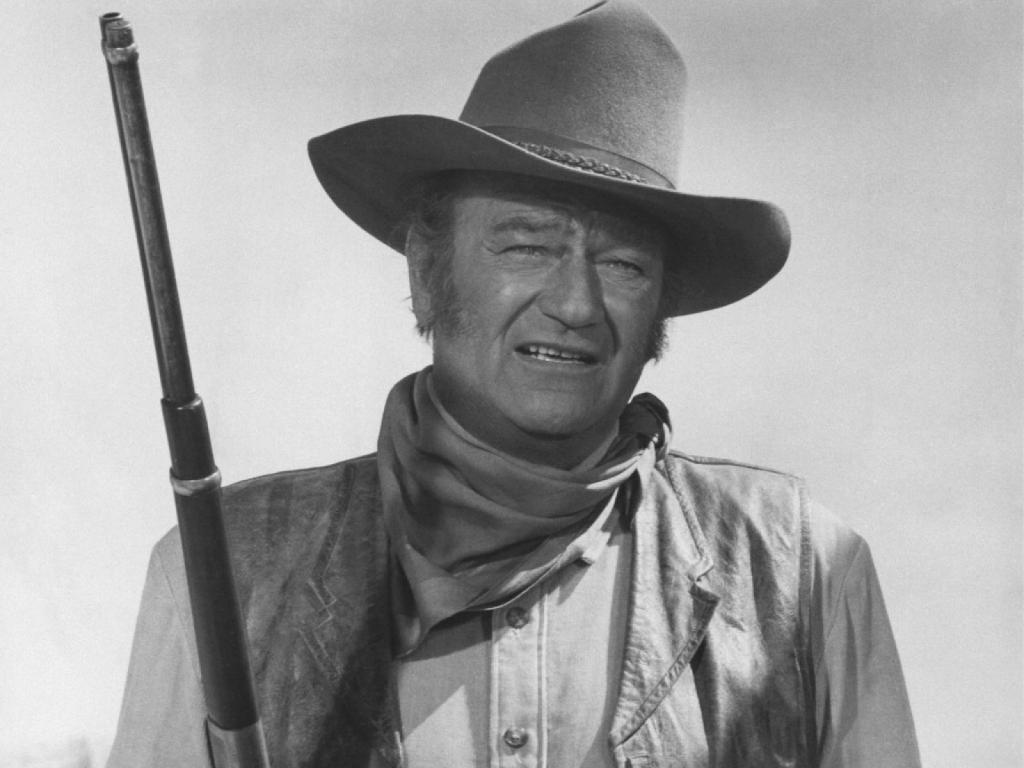

MV: It might be more perverse to love, say, Toby Keith.

KS: I guess so.

MV: I’m just saying that from Colon on the Cob, a terrible noise band and the first show I ever saw you at, to Toby Keith, who you love to write about, there is a line…

KS: Sure. Although when you say Toby Keith, what you actually mean is George Strait. Because George Strait makes actual conventional music and actually believes strongly in the value of convention.

JC: Sorry, these are country music people?

KS: Yeah. Whereas Toby Keith is himself perverse… which might mean it’s hard to be perverse by liking him. [Laughter] That’s what I mean. When I talk to some people, it seems still liking music at all is a fairly perverse position to take.

MV: Point taken. Though perhaps part of what I am again falsely suggesting is an element of perversity at the level of race.

KS: Among other levels. Though that reminds me — I wanted to ask you about breakcore again, Jace. Because even for those of us who never cared that much about Boyd Rice, it seems to me there has always been a racial component to noise. Like, the whiteness of noise seems pretty fundamental to how it exists as a scene. Fundamental to its appeal, even.

JC: Huh. That’s entirely possible. But I guess the noise that struck me the most was the weird stuff from Japan. It struck me as slightly… “other.” When I think about punk and hardcore, which I did not get into in high school, probably one of the main reasons was… Slapshot. You know, Boston racist skinhead dudes. But then with noise, there was this other music that had all that aggression, but totally filtered and exploded…

KS: And multicultural, sure. But breakcore…?

JC: Was it whiter than jungle? Yes…

KS: What I mean is… Often with a subgenre that’s like a noisier version of x — often x is a black music, and the noisier version involves white people. Very recently that could be, adding noise to jungle. But we can go back and talk about distortion and amps… We can talk about rock abstracting itself from blues.

MV: Post-punk abstracting itself from funk.

KS: Right. And often the impulse to make something noisier is to make it less black, or to make that connection more complicated, or to acknowledge the self-consciousness of that indebtedness. There’s something that makes me suspicious about that process…

JC: I agree completely. Partly my mixtapes come from… reversing that process? Certainly by the time my interest in breakcore faded, it was this formulaic, “Okay, here’s the sample, here’s the distorted Amen break.” With the sample being so obviously a black male Jamaican voice serving as sonic signifier of hyper-masculinity, of violence and danger.

KS: But even there, when you’re talking about a distorted Amen break — what does the distortion add to the break, sonically or culturally? Is it a way of insisting that you’re not overly reverent?

JC: Yeah, definitely.

KS: But in the hands of white producers and DJs, what does it even mean for them to be insisting strenuously that they are not overly reverent of the Amen break? Or to have a punk-rock attitude toward it? I mean, I’m fully prepared to admit that this is part of the appeal of noise music; the racial coding of it is kind of interesting. I think for a generation of white music fans, there is an association of noise with a certain kind of authenticity or pugnacity, related to the perception that that authenticity is what’s missing from commercial black pop music. Until Timbaland or whatever… [Laughter]

JC: In all honesty, that’s not the way that any of these kids who were making breakcore were thinking about it. That’s not how sample culture works! [Laughs] People had no idea who played the Amen break; they didn’t know that the origin was this black Motown funk band or whatever. Especially in the UK, it was a conversation that records were having with records. And especially in the context of London, jungle was a really multiracial thing. So to be like, “Oh, they’re putting on distortion” — it wasn’t so simple. That racial dynamic you describe is real, it’s true in all kinds of cases, but the bizarre world of UK dance music in the ’90s was a weird singularity and needs to be treated as such, I think.

KS: Maybe. I just think that despite its seeming abstraction, or because of it, noise in the way that we are talking about it has a particular cultural legacy. Obviously it’s not culturally neutral. It might seem culturally neutral — people might be encouraged to think of it that way. But there is something about the way those noise guys think of themselves or are perceived as being part of a tradition of underground Western popular music.

MV: I believe John Cale once attempted to describe a genealogy of avant-garde rock music that ran from the “purely rhythmic section” of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring to the Velvet Underground…

KS: …and then Metal Machine Music. That’s sort of the piece I thought I was going to read when I read “The White Noise Supremacists.” [Laughter] I was like, “Oh man, he is going to get into the aesthetics and the politics of what it means to distort a guitar. What is being distorted there, brother?” But no, it turns out that people used the “n” word at CBGB’s. [Laughter] The other part of it is, I think it’s important to say — I can’t speak for Jace, actually, the more educated and cultured person — but when it came to Japanese noise, I had no idea what was going on. Obviously there was some context, but most of it, I was just making up and supplying myself. I didn’t know that history, really — I certainly didn’t then.

JC: Yeah, I certainly didn’t then, either. It’s interesting, though, because I’ve been to Osaka maybe twice now.

KS: Is that where that stuff was from? I had no idea where those guys lived.

JC: Yeah, that’s where a lot of that stuff is from… Hanatarash, Yamatsuka from the Boredoms. And people still talk about them in, like, reverent terms.

KS: Oh, really?

JC: There will be, like, a noise bar, just a little bar where all they play is noise music. [Laughter] You know, quietly. There is a real sense of Yamatsuka as a figurehead in that town. There are still a lot of people there who are engaged in differently freakish activities, but they see him as someone who broke all these rules at the very beginning, so everyone has a huge reverence for him.

KS: Hmm. I remember when Pop Tatari came out, following Soul Discharge. It was on Reprise. Which was complicated to think about, because my friends and I generally did not buy major label albums.

JC: Oh, funny.

KS: And the idea that the Boredoms were in some sense mainstream, or had a position in the Japanese mainstream… was weird. I mean, we knew in some vague sense that there were probably a lot of contemporary classical composers, working out of the classical tradition, who were creating a lot of really strange music. But in high school we weren’t interested in that, precisely because they were composers. It seemed…

JC: Funded and coddled?

KS: Yeah. It didn’t seem rooted. And that’s probably related to why I got into punk and hardcore proper. Compared even to a lot of things I liked in high school, those seemed like really unpretentious expressions of the human urge to make noise. So it’s interesting to hear you say that Yamatsuka is the David Byrne of Osaka. [Laughter] Because when we first heard about him and Hanatarash and the bulldozer, we were like, “Oh, that guy sounds really scary. That guy should probably be in jail. Somehow he’s free. And he makes insane music.”

MV: Do you still listen to noise music, either of you? For pleasure?

JC: Not really. Well… I mean, every time I DJ anywhere, there’s always at least one noise record in my bag. And on my radio show I will play pieces of noise, definitely. I guess I have become snobbier about it? I play a lot of “electro-acoustic” music. And a very little bit of improv, even. So, the noise is still there. But not really the Japanese stuff so much. I meet people who are still big Merzbow fans, and I’m always thinking, Oh no! I’m not sure anyone really needs to buy the Merzbow boxed set. For people who go deep into noise, it seems to me, six months to two years is about the lifespan of that.

KS: I don’t know. It took me a while to realize the importance of context. If I had a context for Merzbow that made sense — if for some reason I had a lot of friends who were into that and also into contemporary classical music and also maybe into free jazz, so that, if we went out, that would be on someone’s iPod, in a mix — maybe I would. Although the fact that it’s hard to create a context for noise music now seems to me like one of its weaknesses. [Laughs] It’s not something some other audiences might stumble across. It’s never going to show up in the background of something…

JC: It’s inherently anti-social.

KS: Although having said all that, I kind of do have the context for it now, which is when I’m at work. I need music that I can listen to and be able to write or read somewhat complicated things at the same time.

JC: Music with words?

KS: Mainly I’m listening to metal, actually, and often I’m listening to metal that is, once again, converging upon noise.

JC: Really?!

KS: I can tell you that if you put my iPod on shuffle, everyone will have a bad day.

JC: This is new music? Like what?

KS: Oh, obscure Eastern European, super lo-fi, often like, one-man bands. They’ll have a ten-minute outro where there’s, like, two chords. In a sense, that’s also noise, but it sounds totally different because they’re coming at it from a different angle. It has a totally different musical history. Part of what I like about it that is different from so-called noise music is that it’s multi-use music. You don’t have to be a noise head to be into it. You could be a… neo-Nazi skinhead. [Laughter] Or you could have been into death metal, but that wasn’t weird enough, so you got into black metal, but then a lot of those bands weren’t true. And then you arrive at this stuff… Of course, a musicologist doing a real musicological study would say, “Noise means nothing in this context.” These days, when you say something is “noisy,” that’s another way of saying it’s old-fashioned. In this decade, there’s no reason anything ever has to be lo-fi.

JC: In this decade, noise would be the sine wave. If anything, it’s the clean, digital sound that is the noisy sound…

KS: Is this the point at which noise converges with its opposite?

JC: Yeah! The sine wave is at once the cleanest and most piercing of sounds…

KS: Because if a sine wave is noise, what’s the opposite of noise? I guess, silence… if it’s quiet. [Laughter] I mean a lot of those old noise records really sounded like loud silence.

JC: Silence can be very violent. I remember once I was DJing at this big druggy club in Barcelona years ago, and I had this noise moment, where I played — I think it was a Masonna record. And they started to cheer. But the context there — it was such a beat-based club, and this was totally interrupting the beat. So they were like, “Maybe it will come back if we start cheering.”

KS: But that’s because in their heads they’re still hearing the beat that you dropped out. That’s like one of those phantom beats…

JC: They know it’s going to come back. Or they hope it will. I think if it went on for more than two minutes, people would get upset.

KS: Sure. A noisy event, if it’s short enough, is just a pure rhythmic event. Noise can’t really be short. [Laughter] Have you ever cleared the floor by accident, with Masonna or something?

JC: No. In the DJ context, it’s always, like, noise as tool. The fun thing is to use the blast to bring it back to some other beat. It’s easier to clear the floor with a bad dance record than with a weird noise record.

KS: There’s something, also, about having it done to you rather than doing it to yourself. It’s as though the purest noise would have to be self-inflicted. [Laughter] When you’re talking about noise as this perverse, end-of-the-line listening experience, you kind of have to press play yourself. Otherwise you’re just talking about a sound check gone horribly wrong. And there’s nothing particularly radical or insane about someone who doesn’t know how to work the PA system. Embedded in the idea of noise music, the part that makes it weird or perverse, is the fact that you’re seeking it out. Often, in those days, at great expense and effort. Kim’s on Bleecker would charge, like, twenty-three bucks for a CD!

JC: Import prices, it’s true.

KS: And the fact that you’ve paid for it, and the fact that you’ve taken it home, and pressed play, is what separates it from a garbage truck on the street. Or in a playful way, it’s the distinction you tried to refuse to make. But I mean, if you think about it, it wasn’t — talking about Merzbow, for example — it wasn’t that we’d never heard anything that sounded like that. It was that we’d never heard someone who bothered to put those sounds on a CD.

JC: That’s so true! It’s, like, a coffee grinder sounds like that. Static sounds like that.

KS: It wasn’t foreign like someone else’s language might be foreign. It was entirely a creature of context. And I think, too, that noise was a thing that worked neatly in those two or so decades between the rise of independent record labels and the fall of record labels. [Laughter] People putting out records, not looking for or expecting hits. Maybe you saw it with Metal Machine Music a little earlier… though even that was heard slightly differently because of who Lou Reed was, and the argument tended to be more over what the record meant than what it sounded like. But that whole cottage industry of independent music, the fact that those records were worth something, was actually part of what gave them meaning. And part of what was radical about them, or felt radical, was not that people were saying, “Here’s this noise” or “I’m making noise,” but that people were saying, “This is valuable.” The most radical thing about that record was that it was worth twenty bucks. That’s insane. [Laughter]

JC: But the fact that us fourteen-year-olds, on the East Coast, mostly, were listening to bizarre music coming from Osaka, presupposes, if not a global network, then a dispersed and strange community of listeners out there.

KS: Sure. But in an odd way, if you looked at the music of Japan, it’s funny that that stuff would probably be the least confounding to us. If you’d played us some Japanese rock band, we would have thought, “This sounds like bad x or bad Y.” The fact is that noise was intelligible to us. If you were optimistic or idealistic about that music, you would say that that was because it was a really raw, vital burst of something that was universally understandable. Or you could say, no, this was a group of musicians playing by rules we understood, whereas most musicians in that country were playing by rules we didn’t understand at all. So in a very literal sense, noise music was the most accessible Japanese music in America. [Laughter]

JC: Oh, boy.

KS: It wasn’t a coincidence. I mean, we now know that those Japanese dudes had listened to a lot of the same records. They had actually listened to Metal Machine Music. I mean, it seemed so exotic for you and I to be hooked into this network. But the interesting and maybe depressing thing was that you could go to a noise store anywhere in the world, and they would have had a lot of the same stuff.

MV: Though you had to find that noise store…

KS: But that’s what I mean. Those networks being a weird thing, internationalized.

JC: But the thing you have to remember is that it was utterly marginal. The vast majority of this stuff got almost no exposure. Even compared to other kinds of experimental music — the distribution was terrible. You could go into any “alternative store” in America and get Throbbing Gristle’s greatest hits. But you would be very hard pressed to find a The Gerogerigegege record. So… I’m still thinking about what you were saying before about the “noisier version” representing the whitening-up of black music. Because it’s also the case that the “smoother version” represents the same thing, in reverse. Look at kuduro. European bass people are taking this noisy, relentless, really hard-to-listen-to music from Angola, and being like, “Maybe if we pull the levels out of the red and give it more of a dynamic song structure — make it less of this kind of insane banging techno — and, you know, sharpen up the stage presence, then we will have something that can play music festivals.” They’ve tried to do the same thing to funk carioca from Brazil — you know, take away the noise and then market it.

KS: What do you mean by noise?

JC: Well, they take away the actual bad recordings — the overloaded microphones, the sonic annoyances. The distortion would be removed.

KS: But would those things you describe — would those be heard, within Angola or Brazil, as an important part of that music?

JC: Hmmn — true, no. They wouldn’t.

KS: Or would those people be psyched? “This shit sounds great now!”

JC: But re-importing that stuff doesn’t work. Funk carioca in Rio is just ridiculously loud. There are, like, two hundred speaker stacks. It’s all about overwhelming phenomenal sonics. There’s a lot of shouting, a lot of very overtly noisy elements, both culturally and sonically. But of course, that’s not going to sell in Europe. So the acts that have made it out of Brazil — the first funk carioca band to make it abroad was Bonde Do Role, a bunch of middle-class kids who grew up pretty far from any urban center where funk carioca was popular.

KS: Like Hamden, Connecticut. I guess it’s always the same conundrum with world music anyway: why is this the stuff you like? Of all the genres in Africa… why is kuduro hotter than hiplife? And noise raises a lot of those same questions. Obviously, things change, and it’s not impossible to imagine a world where noise signifies its opposite. Which would be totally interesting — a world in which, in America, treble signifies black and bass signifies white. [Laughter] But for now, anyway, white people’s attachment to noise seems pretty primal. I’d almost call it primitive. It seems to touch something in them…