On February 14, 2005, the day Rafik Hariri was assassinated, I was sent to confession for the first time. I was ten years old and in the fifth grade at a Catholic school run by Lazarists above the bay of Jounieh. Our headmaster had called an emergency assembly in the basketball court. A car bomb had exploded outside the Hotel St. George, he announced. The former prime minister was dead, along with twenty civilians. Hundreds more had been injured.

Glee is not an appropriate reaction to news of an atrocity. Even as a child, I knew that. My friends and I shot one another glances, trying to stifle our grins and mimic the look of serious concern on our teachers’ faces. But all it took was one of us to crack and let a giggle float free for the rest of us to lose composure. Soon, we had erupted into open, flagrant laughter.

Our headmaster glared at us from his lectern, but I wasn’t overly worried. He would assume — I thought — that we weren’t laughing at the detonation itself, or at the deaths or the torn limbs of innocents, but at the prospect of a day off from school. This wasn’t our first emergency assembly. In Lebanon, politics proceeds not by election, but by emergency, and we had learned that when political events of this magnitude occurred, recess was our reward.

That afternoon, we were pulled aside and scolded. This was a moment for reflection and mourning, the headmaster admonished us, and our response had been insensitive and unchristian. We would have to face the moral consequences of our actions. He marched me and my friends from the gym to the chapel, where I entered the dark booth, knelt, and unburdened myself.

My confessor was Father Jean-Mansour, the priest who taught us our weekly catechism and was known for delivering fiery Sunday sermons on the seductions of pop music and homosexuality — sermons that had earned him invitations to appear on Beirut’s Christian radio stations. Young, doctrinaire, deathly serious, physically imposing, Father Jean-Mansour was precisely the last person I should have been honest with. And yet in response to the question “Why did you laugh?,” I heard myself admit the truth: It was not simply because class was canceled, though that was a perk. I had found the assassination, the bomb, the prospect of seeing the crater in the downtown streets — I had found it all exciting.

Father Jean-Mansour, who had been kneeling inside the other end of the booth, stood up, looked straight down at me, and delivered judgment. Mass murder was not a game, he said; it was a cause for grave concern. We should all be praying that it does not escalate into further violence. Did I find the death of the prime minister titillating?

I shrugged, then sat in stubborn silence as he berated me. I could hear the voices of the louder kids drifting in from the playground outside. They were chattering with excitement about the “situation,” as if they’d just come out of a Jean-Claude Van Damme movie. The priest gave me and the other guilties an ultimatum. Unless, by the end of the year, we had ceased to feel a spine-tingling sensation at every car bomb, assassination, or street fight, he would have to call our parents and urge them to seek professional help for our sick souls.

Was inappropriate laughter our inheritance? For the most part, my generation was raised by cheerful militants. Parents, neighbors — anyone old enough to credibly claim a piece of the action — openly reminisced about carrying firearms and tossing hand grenades during the Lebanese civil war of 1975–90. These stories were told with bravado and mirth, as if the parade of battles, sieges, and massacres had been nothing more than a game. Maybe that’s why we’d failed to grasp the cruelty of a truck bomb. Whenever I glimpsed the edges of conflict peeking out into everyday life — and it appeared often as I was growing up, in armed scuffles between militias, in sudden waves of panic buying, in the prophesies of celebrity clairvoyants who shared doomsday forecasts on television — I would secretly look forward to the spectacle to come. It was, I guess, a sort of entertainment.

At first, I tried to take Father Jean-Mansour seriously. I rehearsed basic methods of restraint, self-discipline, and gravitas. But our immediate circumstances weren’t of much help. Within the span of a single year, dozens of car bombs went off outside shopping centers, bingo halls, factories, and hotels, targeting prominent political figures, including journalists Samir Kassir and Gebran Tueni, and former secretary general of the Lebanese Communist Party George Hawi. The bombings would continue throughout my adolescence, most memorably in 2013, when Friday worshippers outside the Al-Taqwa and Al-Salam mosques in Tripoli were targeted, and in 2015, when dozens of pedestrians and shoppers in Beirut’s southern suburb of Burj Al-Barajneh were killed.

Around the age of twelve, I began detailing these occurrences in a worn-out address book. Inside, I stapled graphic postmortem photographs of the victims alongside short, handwritten biographies that I cobbled together from Google searches in an internet café, where I was surrounded by boys playing America’s Army. To each entry, I added my own legend: black dots for killings by the Syrian regime and Hezbollah, red dots for isis, and green for Fatah al-Islam and groups linked to Al-Qaeda; blue dots (there were many) pointed to the Israeli intelligence services.

Later, I found out that I wasn’t the only diligent scrapbooker. There were the artists Walid Raad and Ali Cherri, among many less famous others. In his Atlas Group project (1989–2004), Raad compulsively collected photos of engines found strewn across Beirut, the detritus of more than 245 car bombs that exploded in the city during the civil war. Cherri confessed in a 2005 lecture that as a teenager he would collect images of nude corpses because he couldn’t get his hands on real pornography. His private collection included photographs published in local newspapers; the splayed, inanimate bodies became framed as memory sites charged with libidinal desire. My own archive was also a projection of fantasy. By filling up my notebooks in this way, I fantasized that there was distance between me and these fatal scenarios, that they would never happen to me or anyone I cared about. The urge to archive became a kind of respite from my own helplessness.

Father Jean-Mansour never remembered to schedule a follow-up session in the confessional. We never did discuss my psychic “progress,” and over the years, the sociopathic tendencies he detected in my laughter continued to flourish. After I dropped out of college, I began working in Beirut newsrooms, where, as a junior staffer, I was charged with calling up emergency-room receptionists to confirm death counts and hounding witnesses for their amateur footage of atrocities. There was plenty of misery to document, and I found myself being paid to do it. The Assad regime was four years into its extermination campaign against its own people; in Lebanon, mounds of untreated garbage filled the streets as a result of systemic mismanagement, poisoning thousands and triggering a cycle of protests and heavy police repression. The outside world had been reeling, too. 2015 was a year of populist surges and terrorist attacks in liberal European republics, while the Mediterranean turned into one of the Earth’s largest mass graves.

For me and my colleagues, tragedy was opportunity. We traded solemnity for amusement, heartache for glee, and lucidity for vodka-laced Red Bulls and Turkish coffees. At a certain point, though, the continual breakdown of our social order lost its appeal as fodder for drinking games. The closeness of danger began to asphyxiate. If there was a turning point, it did not arrive in the form of another explosion, political assassination, or militia face-off. It was the day we learned that there are other, more insidious ways to die.

Lebanon’s central bank was not among our traditional list of villains. The Syrian occupation and its shabiha, the Israeli Defense Forces, the state and its security apparatus, the countless Islamist factions that sprang into and out of existence, the real-estate contractors and their bulldozers — these were the forces that we could expect to one day destroy our homes and take our lives. Banque du Liban, on the other hand, was a business-school case study: the sole sober institution in the midst of all this dysfunction, and one that had shrewdly guided us from economic devastation to a semblance of stability through three decades. Little did we know, though, that it had been operating a Ponzi scheme for a while now, borrowing money from local banks to pay off debts while feeding reserves with expatriates’ dollar remittances and foreign aid, in order to cheapen imports and sustain the illusion of a healthy currency.

It was only a matter of time before the scheme collapsed. We learned the hard way that we were living in a house of cards in August of 2019, when many of us were suddenly unable to withdraw US dollars from our bank accounts, or liras above a limited amount. Paying an urgent medical bill, or fixing a broken phone, or buying a plane ticket online, became impossible. On October 17, 2019, the government, then headed by Saad Hariri — son of the slain former PM — had decided to implement austerity measures, which included an absurd tax on free internet calls. Hariri fils was still nursing his wounds from a scandal that involved his gifting $16 million to a white South African lingerie model and was struggling to lead his corrupt party, blandly named the Future Movement. Its parasitic involvement in the privatization of the capital’s seafront and downtown area had raked in billions for its cronies.

That night, hundreds of thousands of angry demonstrators assembled in the streets of Beirut to demand the toppling of the sectarian-clientelist regime. It happened to be the opening night of the eighth edition of Home Works, a biannual cultural forum I’d spent the past few months organizing with colleagues. Curators, artists, and journalists who had come to look at Etel Adnan’s early pastels suddenly found themselves in the midst of a volcanic eruption, unable to get to their hotels or the airport on roads blocked by burning tires. My colleagues and I left our event at an art gallery to join the protests in the streets, which we intuitively felt had the potential to reconfigure everything.

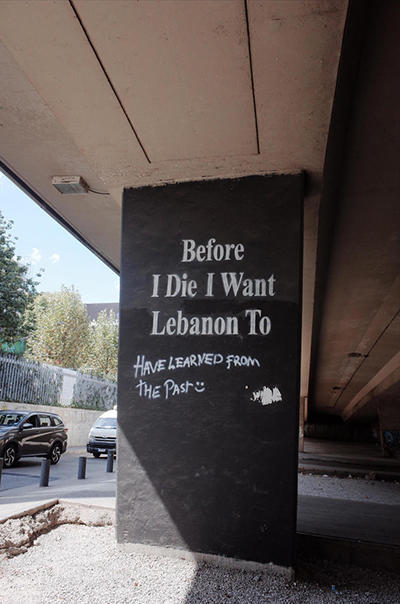

From there, the insurrectionary fervor spread across the country, from Tripoli in the north to Saida and Nabatieh in the south. For weeks, general strikes disrupted the humiliations that had become an inescapable part of our daily lives. Highways turned into skate parks and government buildings became stages for mock trials. Rich neighborhoods, their inhabitants having flocked to second homes abroad, were occupied by popular committees giving out free food and medicine. Protesters targeted the physical infrastructure of corruption — banks, ATM machines, and currency exchanges, as well as party headquarters and government buildings. With flame torches in hand, we sought to occupy and dismantle them.

It felt like a beginning — the outset of a project of tearing apart, or unlearning, thirty years of public dissimulation by the rotten corpse of the government. Once again, school was out indefinitely, and the feeling of unrestrained excitement that had gripped me during my childhood came back with a vengeance. This time, though, I wouldn’t need to conduct mental acrobatics, nor to practice confession with Father Jean-Mansour, in order to justify my desire to witness, and take part in, carnage. There was acceptance in sharing phantasms of decapitations and cities catching fire. I didn’t bother to join nascent political groups or to report on political happenings; instead, I reveled in the doom and took in the scenery of insurrectionary violence any chance I could. I would run off in the middle of the night to watch teenagers destroy a luxurious Range Rover outside a parliamentarian’s house or to stare at the gore of an injured police officer being treated on the street. Everyone was burning with fever, but no one was begging the war to stop.

In late February 2020, the first confirmed cases of the coronavirus were reported in Lebanon only two weeks before the government announced it would default on the payment of a $1.2 billion Eurobond — a decision that implied the country would soon go bankrupt. The security forces had been arresting and disappearing activists who participated in the October uprisings, but soon the coronavirus would complete their work of repression. The state enforced a total lockdown, and for many of us, a sense of panic set in, prompted by our deep-rooted distrust of Lebanon’s crumbling hospital infrastructure.

The months in lockdown were arduous; with each day that passed, I seemed to accept, with increasing indifference, that grief would steadily assail me and there was little I could do. Perhaps most of us were already grieving the future devastation, a process that had effectively begun with the financial crisis, sending the currency into free fall and shattering already precarious communities. Earlier that year, we had managed to storm public squares and chant emancipatory demands, but now, in quarantine, we were being asked to bury our insurrectionary movement once and for all or else risk spreading the virus among ourselves. In a televised address, Hezbollah’s secretary general, Hassan Nasrallah, proclaimed the pandemic a “battle” to be fought “over the entire Lebanese territory.” The irony wasn’t lost on us that the last time we had been ordered to shelter in place was during the July War of 2006, when the Israeli Defense Forces launched an unrelenting attack on south Lebanon and Beirut, targeting homes, schools, and hospitals. Thousands were slaughtered then. Now, we hoped this new “enemy virus,” in Nasrallah’s words, wouldn’t finish the rest of us off.

Isolation meant a new sort of alienation. Those of us with some form of stability grew divorced from the humiliations and dispossessions taking place across the city. Mass evictions hit working-class neighborhoods, small businesses shuttered, wages in most sectors dropped in value by 60 to 80 percent, and the price of essential, imported goods quadrupled overnight. Domestic workers from across Africa and Southeast Asia were abandoned by their employers, who deposited them near their embassies; desperate families bartered household objects for diapers and infant formula on Facebook. There was talk of famine and of a coming extinction, like the blight that struck the Ottomans during World War 1, when locust invasions, blockades, and mass starvation obliterated entire life-forms on Mount Lebanon. Politicians encouraged us to grow our own potatoes and cucumbers; a party-owned online media site published daily articles on the medicinal benefits of weight loss. Clergymen appeared on the nighttime news calling for resilience and recommended we extract spiritual value from our neighbors’ pain.

The scandals continued to break. Riad Salameh, the governor of the central bank, was exposed for investing in offshore assets worth $100 million. Meanwhile, wealthy Lebanese emigrants, feudal heirs, and partisans of the ruling oligarchy loudly lamented the disappearance of a “Lebanese way of life.” What they were really mourning was the fantasy of unfettered entrepreneurial triumph and unrestricted capital flow, which had long since curdled into a cliché about Lebanese exceptionalism. But the nation the trope evokes could only be sustained by granting immunity to the former warlords and tax evaders, the human traffickers and land-grabbers, the speculators and money launderers who have made it their playground, indulging in an economy of unbounded inequity. It has forced the rest of us to stand in endless queues outside banks to receive our monthly allowance and entrapped hundreds of thousands of migrant workers from Africa and Southeast Asia in the kafala, or sponsorship, system. This was, to put it simply, not the lost future we were mourning.

On August 4, 2020, I broke quarantine and left Beirut with some friends and my former partner, Bassem, to go swimming on the southern coast in Tyre, the rare strip of sand that has escaped the hands of real-estate developers. My astrology app told me that the moon in Aquarius connected with Mars at 2:45am that morning and that I needed to cut myself some slack. We’d been under a partial lockdown for a couple of weeks, and the city, amid the still-unfolding financial collapse, had become unbearably gloomy. The only talk on the streets of Beirut was of foreclosure and deprivation.

We’d ordered fried-shrimp sandwiches at a fisherman’s shack when a WhatsApp group created to coordinate road blockages and sit-ins during the October uprisings blew up with hysterical messages. I played aloud an audio note from a woman known for her equanimity and composure during scuffles with riot police. She was overwrought with horror, insisting she had been targeted by an airstrike. I couldn’t understand much else. The group text was a scroll of frantic punctuation marks and “Are you okays?”; cell service was too weak for actual calls. The cashier called us inside, where his compact TV was broadcasting live footage from the headquarters of former PM Saad Hariri, who had resigned after the initial stages of the October uprisings. News reporters had rushed there, assuming there had been an assassination attempt.

A friend caught me trying to conceal my nervous laugh, just as I caught her doing the same. At some point in the summer, we had bonded over our guilty attachment to the kind of disorderly gossip that would accompany car bombs back in the day. An unharmed Hariri soon appeared onscreen, entering the lobby of his headquarters to reassure the crowd that had gathered. Maybe the loaded vehicle had missed its target, we thought.

After five more minutes of watching confused anchors improvising on-air to kill time, videos of a gargantuan cloud of pinkish smoke above the Beirut port started circulating on WhatsApp. It was bewildering at first, though not frightening, because the shots appeared abstract, taken from a safe distance at sea. It was only when we were finally able to reach loved ones that things started falling into place: my mother breathlessly informing me that my father’s dental clinic had crumbled into ashes while he’d been working inside; a friend asking if we knew of a hospital that could tend to a colleague who had been dismembered; another friend who passed by piles of either dead or inanimate bodies, he wasn’t quite sure, while searching for his dog; a breaking-news headline from Reuters claiming authorities had declared Beirut a “disaster city.” What made these bits of information all the more destabilizing was that they seemed to emanate from many different neighborhoods in the capital. We didn’t know whether this had been another of Israel’s spectacular declarations of war, or whether the explosion — 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate, as we later learned — had released toxic chemical agents into the air. We sat inside our parked car and waited. Beirut was far from Tyre, but the city was usually faintly visible from the shore. As night fell, we noticed that a chunk of that familiar skyline and its lights had been extinguished, as if part of the city had been wiped clean off the face of the Earth. We’d narrowly missed out on our own annihilation.

There have been many testimonials about August 4. But the minutiae remain, to this day, a blur. To recount the aftermath of one of the most powerful nonnuclear explosions ever recorded is to assume a responsibility toward its countless victims, a responsibility made all the more paradoxical by our inability to grasp atomized suffering or to craft an adequate narrative of loss. All in all, within the space of precisely two minutes, between 6:07 and 6:09pm, two hundred and eighteen people were killed, seven thousand sustained mild-to-life-threatening injuries, and more than three hundred thousand were rendered homeless. Here, language hovers at the edge of treason; any attempt at recollection, or at registering in writing a collective lived experience is preordained to fail.

How does one write of the mother of two crushed by a closet while protecting her children’s playmate? What about the retired schoolteacher decapitated by his bedroom ceiling fan mid-nap; the newly wedded couple who buried their three-year-old daughter; the theater student trapped between two walls while working an extra shift at a seaside cafe; the sanitation worker who, after having been sacked by the American University of Beirut Medical Center a month before, disappeared at sea during his first week on the job at the port; the Palestinian refugee who saw his makeshift home collapse on top of his wife and two daughters? How to speak of the ten firefighters, nine men, and one woman who were ordered to put out the flames racing up the warehouse storing the ammonium nitrate right before it exploded, whose body parts have yet to be retrieved, or the dozen Ethiopian, Bangladeshi, and Filipina domestic workers killed inside their tiny “maid rooms” and never identified by their employers?

The months that followed provided neither respite nor time for mourning. We had once again been humiliated to the core and reduced to being spectators of a tragedy-cum-farce. The reinstatement of business as usual was swift and ruthless, though not a single day would pass without disruptions on the painful road to recovery. Thousands of young volunteers worked to coordinate the cleanup in Beirut’s most-affected neighborhoods, only to face aggression and disdain from authorities who saw every volunteer as a potential thief. On August 8, a mass protest bent on avenging the dead ended in blood, as the riot police, accompanied by soldiers and militia thugs, shot live ammunition, rubber bullets, and metal pellets at protesters, sending hundreds to nearby hospitals.

Lebanese president Michel Aoun, all smiles and cheers, congratulated himself on live television on the fact that the explosions had “broken the siege”; previously, all foreign aid to the country had been blocked as a result of Lebanon’s defaulting on its loans. The government resigned two days later after a mere six-month stint, leaving behind a fascistic military state of emergency to contain and suppress popular rage. FBI investigators, along with their French and British counterparts, waltzed into the port and set up shop. French president Emmanuel Macron embarked on a narcissistic journey to reclaim the French colonial empire’s “protective” reign over Lebanon and met victims’ families on-site. He paid a well-publicized home visit to the notoriously media-averse Lebanese chanteuse Fairouz, who had been hibernating for the past two decades outside the city in a kitsch apartment filled with drawings of herself sent to her by fans. An online petition asking for Lebanon to be placed once again under a French mandate, as it had been in the early-twentieth century, garnered sixty thousand signatures overnight.

The Iranian Red Crescent Society and the Moroccan military forces each set up field hospitals in the city; the government of Sri Lanka donated 1,650 kilograms of Ceylon tea, which ended up being distributed only to soldiers in the presidential guard. Kuwait offered to rebuild the port’s grain silos, which had absorbed 70 percent of the explosions’ shockwaves and had since become a landmark in their own right as a backdrop for selfies. High-end restaurants, art galleries, and cultural establishments made anguished appeals for money to refurbish their spaces as greater numbers of the city’s residents sank into food insecurity and homelessness. A sleeper cell affiliated with isis was reactivated in the North; its members were arrested on suspicion of planning future terrorist attacks. Benjamin Netanyahu, during a nauseating United Nations address, warned inhabitants of Beirut’s Jnah neighborhood that Hezbollah was “storing weapons near a gas company,” prompting legitimate fears that he was yet again threatening a full-fledged war.

We have given it many names — an unfortunate accident, an Israeli airstrike, a foreign conspiracy to bring Beirut to its knees, a state-engineered massacre, a crime against humanity. We have consumed and debated empirical proof, forensic insights, audiovisual material, and classified-document leaks, to the point of exhaustion. Yet every attempt at truth, accountability, and justice seems to fail; the event itself falls outside the domain of reason.

Many have given up on trying to “find out” what exactly happened on August 4. The Victims of Beirut Massacre group sought to have its letter to the UN Security Council demanding an international investigation endorsed to no avail. Those with dual passports, active visas and scholarships, or family abroad have fled. The majority continue to wrestle with a grief that feels infinite and makes any bodily pain seem trivial. We amble through our disaster city in a daze, occasionally bearing cash collected from an emergency relief fund in New York for the victims, but mostly to unsee the sights and scenery, to visit the ruins or film spaces where we’d once been on ketamine, or had a notable fuck, or led a reading group, or met a loving stranger.

Precisely one month after the blast, we froze, for what felt like endless hours if not days, waiting on a Chilean search-and-rescue team who had detected a heartbeat in the rubble of Mar Mkhael. We insisted on camping out in front of the rescue site until the survivor was unearthed and identified. International media spoke of a potential miracle and reported “a newfound sense of hope” among Beirut’s broken inhabitants. It was trivializing, if not grotesque, to frame our collective insistence on finding life amid the rubble as “hope.” There wasn’t a shred of it to be found, nor was there a body to resuscitate in the wreckage.

On the day I was baptized, my grandmother, a frigid woman with an unmatched sense of cynicism, kept surreptitiously pinching me so that I would cry, a sign that I had been admitted to the Christian church. She never lived to see the explosion of August 4, and in the months after it, I never wept, although I felt that I should have. Instead, I’d sit and watch, again and again, in torturous slow-motion, amateur footage of the ammonium nitrate laying Beirut’s skeletal architecture bare.

A year after the event, I found myself on a flight from Amsterdam to Beirut, carrying more than three-hundred boxes of medication to distribute among family and aid groups. However accustomed we had become to state violence and negligence, the situation had reached a new height of catastrophe. Most hospitals were closing down amid medical shortages; residents were facing uninterrupted electricity cuts lasting days and weeks; thousands lined up in their cars and on motorcycles for endless hours in front of gas stations, blocking the highways, desperate for the scant remaining fuel that hadn’t been hoarded by the ruling class. If the country had been hurtling toward collapse at an alarming speed in the past couple of years, it was now in utter disarray. On the streets of Beirut, the chaos was matched by a deathly stillness and silence.

I got home to my parents and unloaded my luggage using a flashlight. Usually the smell of a stew with peas and rice simmering on the stove would greet me, but keeping food in the fridge, or preparing anything but the simplest meals, had become impossible. My father seemed content with the nose patches I’d brought him to stop his snoring. Most of my family was now sleeping in my childhood bedroom because it had a powerful fan. The small room felt like a fortress; somewhere in it was my notebook of explosions past, safe and sound. As I allowed the fan to lull me to the brink of sleep, I started to cry, not out of anguish but in acknowledgement that, at least for now, we are still here.