Damascus

Ammar Al Beik: Colored Earth… Black Chainsaw

Ayyam Gallery

June 26–August 5, 2010

Can one possibly compare a gallerist to Saddam Hussein? In the overheated atmosphere of the Damascus art scene these days, it’s been known to happen. As debates about new private galleries, their profits, and the legitimacy of their legatees rage, choice analogies have begun to fly. In an article published this summer by artist Yusuf Abdelke in al-Safir newspaper, it was Khaled Samawi, the founding director of Ayyam Gallery, who inspired the comparison to Saddam. (It seems that in one interview Samawi expressed pleasure in annihilating his competition.) Crafting a rebuttal for the same newspaper, Safwan Dahoul, the gallery’s top-selling artist, dismissed the victims of market brinksmanship that Abdelke had evoked as mere ideological delusions, designating them people who were merely “waiting for Guevara,” as if Syrian artists still anticipated a swashbuckling socialism that would never come.

Such characterizations cut especially deeply in the Syrian art world, where fitful market liberalization has rendered these debates all the more exigent, even if familiar. Yet as op-ed journalistic works, they hardly represent novel forms of artistic critique. For novelty, one might instead turn to artist Ammar Al Beik’s latest show, Colored Earth… Black Chainsaw. In this piece, conceived specifically for display at Ayyam, the artist presented an altogether different type of counterfactual personification. He put an actual object — a big, black, brushed metal chainsaw with the gallery logo custom embossed on its guide bar — forward as a surrogate self. This self-portrait served as the opening element in the installation layout. As such, it literally embodied the potential energy, luxury fetishism, and pervasive sense of impotence that Syrian artists and their audiences have been negotiating on an increasingly expansive commercial plane.

As it happens, Al Beik is one of about fifteen artists in Ayyam Gallery’s Shabab series — a group of thirty-something contract artists whom the gallery represents (think Charles Saatchi’s YBAs in London circa 1990s, only without the shock value and with an emphasis on large painted canvases). The Samawis, who run Ayyam, have invested a great deal of capital into their business. The gallery maintains locations in Dubai, Beirut, and Cairo in addition to Damascus; it buys booth space at some medium to high profile art fairs; its permanent showrooms are vast and abundantly air-conditioned. Moreover, it runs its own auctions for “emerging collectors,” who might seek the occasional quick and thrilling, if not entirely shallow, purchase. What so obviously drops out of the picture sometimes is much critical engagement or self-reflection. Indeed, Ayyam’s practices flout the art establishment wisdom that first crystallized in New York and London, i.e., that the auction house is an enemy of an emerging artist because its sales format ultimately pushes prices (and careers) up too quickly — and without substance.

It feels fitting, therefore, that in the Damascus showroom, Al Beik kept his artistic persona switched off and under plexiglass. A large tag hanging from the chainsaw handle provided textual notes that, among other things, related a brief parable about a lumberjack and his futile effort to cut down a single tree. If, as the tag concluded, “for a new olive tree to grow, many barren ones must be cut down,” then the chainsaw on offer — branded gallery property — certainly will never meet any such high-minded directives regarding land, labor, or rising again. Instead, the anthropomorphized instrument served to register a set of unresolved problems: consumerism, poverty of thought, the overreach of a gallery’s branding campaign, and the uselessness of revolutionary gestures in recent history.

The rest of the installation worked a bit like a theater set, presenting visitors with a circuit of encounters with additional quandaries. A large-format color photograph of a lollipop invited viewers to linger over its luscious twists and turns (pleasure in consumption); in another corner, twelve readymade devices meant for use in manually spreading stucco and cement hung as sculpture, each stained with the residue of the artist’s own bright, artificially colored paint (appropriation of labor). These were flanked by a series of black-and-white studio photographs documenting the bodies and dress of twelve Syrian construction workers. Each holds the same device in his hands.

The one “painting” in the show may have been the weakest piece. Al Beik gridded out twenty-four miniature paintings in the style of Jackson Pollock, cropped them by means of digital images of gilt picture frames, then rendered them whole again for hanging on the gallery wall. Beside the piece, video footage from its production played on a flat screen monitor. There, Al Beik could be seen bending over a canvas — its surface already pre-printed with frame imagery — using the concrete sprayer to drop skeins of paint into the masked out areas. Reminiscent of an art school parody, both performance and product paid more obeisance to the heroism of the modern period than they could manage to deconstruct.

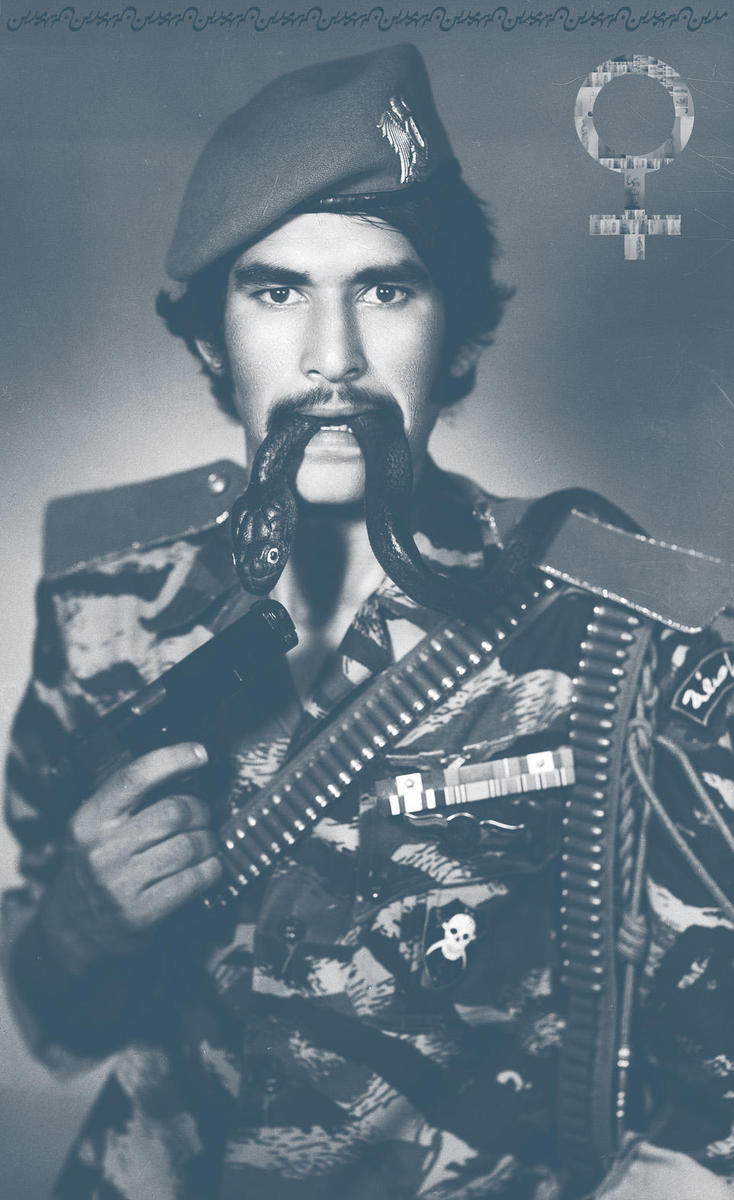

Andy Warhol proved a more effective point of reference (and anxiety) for Al Beik than such riffs on action painting and the readymade. Into his series of photographs of construction laborers, the artist inserted a photographic self-portrait in which he too holds a cement spreading device. In it, he sports a T-shirt bearing a picture of Warhol. It reads, “To be a successful artist, you have to have your work shown in a good gallery for the same reason that, say, Dior never sold his originals from a counter in Woolworth’s.”

Fair enough. Al Beik effectively conveys his misgivings, as well as a sense of hard-won savvy. But in the end, beyond disavowing the myth of creative sovereignty, the Ayyam installation raises the ever pertinent question: Is critique of the art world and its peculiar workings possible when waged from within the gallery system? These pieces do expertly restate the problem in terms drawn from Syrian discourse, in all its rapid shape-shifting. Nonetheless, they still sidestep the question of whether reflexivity (or annihilation, or revolution) is a necessary or even sufficient activity to counterbalance the less palatable aspects of the art business.