Drive along the corniche in Doha tonight and you’ll see the laser lights and heart-shaped fireworks of victory. The ministries and towers of Dafna are festively lit lemon yellow and maroon, while a giant disco ball hangs suspended over Palm Tree Island. “2022” is tagged in gold on the barrels of cement trucks and the safety hats of construction workers. One thousand feet above the street a high-def billboard reflects seamlessly onto the glass surface of the Commercial Bank building: a live feed from an Asian Cup football match, in progress not five kilometers away.

Qatar is building a sports utopia in anticipation of the 2022 World Cup. The denizens of this brave new world aren’t only the finest athletes money can buy (see page 58). There are also the graduates of the ASPIRE Academy for Sports Excellence, which provides locals and foreigners with training in sailing, soccer, squash, table tennis, tennis, fencing, rowing, rock-climbing, and golf.

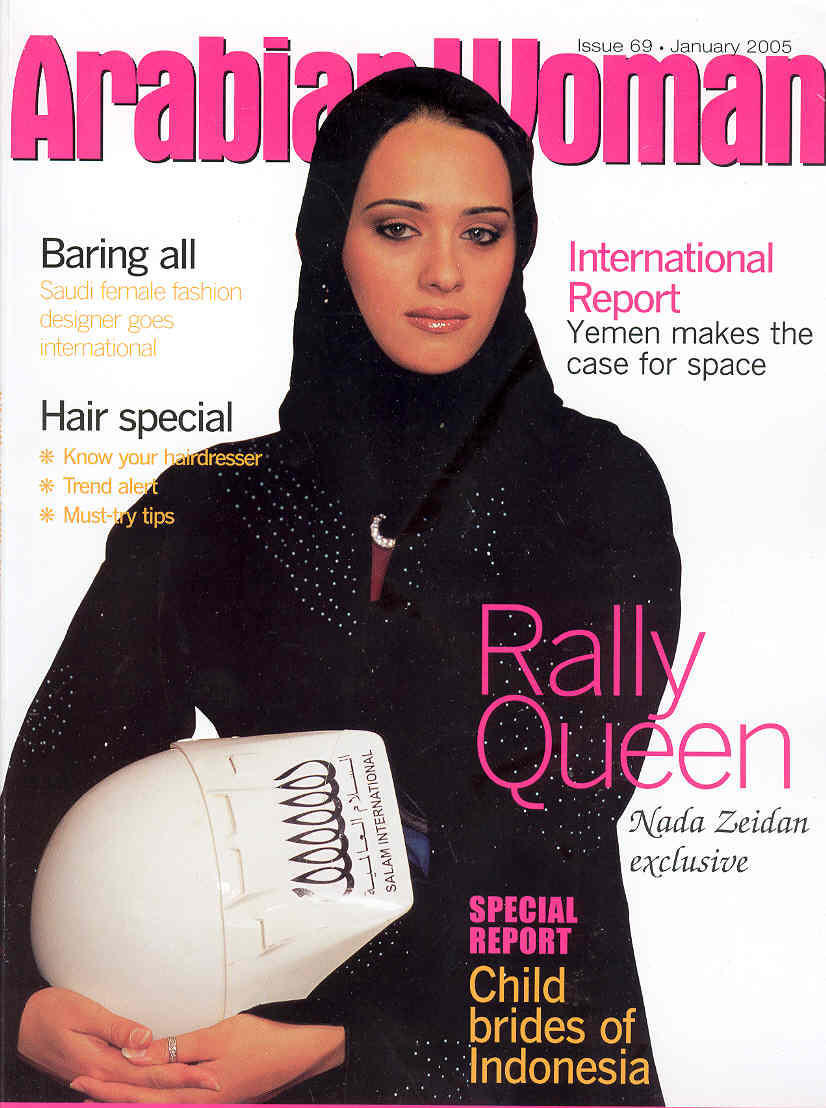

ASPIRE also boasts a state-of-the-art hospital, where, if you are particularly unlucky, you might encounter Nada Zeidan, one of Qatar’s greatest celebrities — archer, spokesmodel, and road racer by day, mild-mannered emergency-room nurse by night.

Sophia Al-Maria: Your website advertises you as a “unique Arab sporting icon,” which is fair enough. I certainly don’t know of any other archer–racers in the Gulf, let alone female ones. But the site doesn’t go out of its way to talk about your secret identity, as it were, as a nurse. But nursing is a huge part of your life, isn’t it?

Nada Zeidan: I always wanted to be a nurse, ever since I was a child. I was born in Lebanon, you know; we left when I was four years old, during the war. I remember the day we left, actually — I remember getting an injection, and the nurse helping me prepare for it. A few years later — I was seven — I saw a nurse on television and I turned to my father and said, “I want to be a nurse.” He said, “You’re too young to be thinking about this.” But it was always in the back of my mind, and when I started secondary school I insisted on a school with a program in nursing. My mother didn’t accept this at first — my cousins were all doctors, and her idea of a nurse was someone who brought dinner and changed the Pampers on elderly patients. But my father pushed me and helped me get what I wanted. Hamdullah.

SAM: Was it hard for you to adjust to your new life in Qatar at such a young age?

NZ: The main difficulty for me was the language. I still remember being reprimanded by the teacher the very first day of first grade. She asked me to close the door but I couldn’t understand what she was saying, and she called me stupid. She thought I was refusing her. That was when I realized that there was more than one Arabic. That was really hard. But I loved being here right away; we left Lebanon during the war and Qatar was a peaceful place where the people were friendly. I think I’m always looking for security, really.

SAM: And yet you love to drive race cars! I guess I’m wondering how you square your career in sports — as an Olympic archer, a rally driver — with this longing for security?

NZ: Well, at the same time, I’ve always enjoyed a challenge — I tend to take to the most difficult route. When I go hiking in Jordan or Lebanon, I like the mountains. I like suffering in the mountains.

SAM: Do you have a sense of why that is?

NZ: You know, I think about this all the time. Why do I want this? Where does it come from?

So many things go back to childhood. I think it might come from Lebanon again, from having to leave suddenly. I know that when I finished secondary school, what I wanted more than anything was to join the army. To be ready for anything! I was just a student, but I knew I would need to be able to handle a gun, to protect myself. This same sense fueled my interest in nursing, of course. When I was doing my studies at Qatar University I tried to argue that we nurses should get the same training as soldiers. So we can be ready.

That didn’t happen, of course. But since they wouldn’t allow me to train with the army, I had to go find what I wanted for myself. I went to a shooting club to learn how to use firearms. And at the club I discovered archery. Archery is the sport our religion encourages most, you know, for both girls and boys. And it requires more physical strength and more concentration than shooting guns.

SAM: So are you into extreme nursing too, then? [Laughs]

NZ: I am! In nursing school, as soon as I could, I started working in the operating theater. I’m always looking for the major cases to help with — trauma, neurosurgery, cardio forensic surgery. I’m always trying to do my best. In the operating room you have to have an instinct about what the surgeon is going to need next, because one small mistake can change everything. You try to be prepared for what might happen. And when there is bleeding and it’s my job to be ready with the plate and the suction — I feel useful, like I’ve really done something.

SAM: Do you see a lot of patients who’ve had automobile accidents?

NZ: Oh yes. I often find myself crying as I do my work, thinking “Oh God, what an end. Whether he’s a good man or a bad man, what an end.” So many times the doctors have asked me, “Nada, why are you crying? Do you know this guy?” But it’s not personal, even. I can’t really explain it. So many of the accidents involve young kids — just boys, really — and they don’t know what they’re dealing with, how dangerous it can be to drive. They don’t think it can happen to them.

When I’m driving in the city, you’d never believe I’m Nada the rally racer. From the first time I ever drove a car, my father told me, “The street is not for you.” I always remember that — I leave the street to the young boys. My sister gets angry at the way they drive — she shouts at them — but for me, I say, Go ahead. I have to be careful, logical. These boys don’t know what they’re risking.

SAM: Do they ever give you trouble? I mean, do you ever get recognized when you’re driving in public?

NZ: I do. But actually the women are the worst. When they see me they always try to race me. I remember this one woman — I think she had a blue Peugeot — she was really crazy. She followed me all through Defna, driving around me in circles, just to show me she’s a good driver. I mean, there are others, lots of them, but I’ll never forget her.

SAM: You do seem to drive people a little bit crazy.

NZ: There are so many negative discussions about me in the Arabic media! “Who is this woman, who allows her to do these sports?” There are so many people just waiting to see me fail and say, “I told you so.”

But maybe that’s why I feel like I have to do these things. I do these things to challenge myself as a woman, and to challenge their ideas of what women are, too. People are always sure the son is doing right and the daughter is doing wrong. I don’t know what makes people think this way. My parents are good, thank God, but they have to listen to people talk about it all the time.

Thank God for Sheikha Mozah. She’s done so much for young women and sports. I think I helped open the door for the next generation, too. We women who go first are the ones who have to suffer.

SAM: You’re definitely an inspiration — and you’re certainly not a stereotypical Qatari woman. I wonder what you think about girls who act and dress like boys — you know, the boyahs?

NZ: I’ve known many girls like this — it’s been an issue in sports for a long time. Of course, first of all, in our religion this is unacceptable. And I’m sure there are a lot of psychological things involved. There’s so much pressure on daughters.

From the outside, I see they are two different persons. I mean, all of us are different people, with and without abayya. But this is extreme. I mean, I challenge this idea all the time by doing sports, but I never ever think of myself as a boy. There were two girls I was teaching and I could tell they were boyahs. They tried to deny it — I said, “Why are you wearing men’s perfume?” And they said, “Oh, cologne works better at hiding smells after you sweat.” I’m not stupid. I know what they’re up to.

I knew some girls like that in university — with a man’s style, the Rolex, the sideburns, the cologne, and the men’s shirts. How they walk. But I don’t blame them. It’s the mistake of the teachers and managers in the sports field. These girls need to be guided, from childhood: What is halal? What is haram? But then, enough. Leave them alone and God will protect them.

SAM: Have you thought about doing the Dakar Rally?

NZ: That’s my ultimate goal, really. But I’m afraid I’ve wasted too much time. My last big race was five years ago. Then I had to stop to prepare for the Asian Games and then I suffered an injury, and it takes so long to get psychologically prepared to get behind the wheel again. But I want to do everything!

SAM: How do you get psychologically prepared to drive a race car?

NZ: I do Tae Kwon Do, which is good for the muscles as well as the concentration.

SAM: Do you ever have problems with the heat here? Do you have to do heat prep or anything?

NZ: No, I’m ready. I spent nearly six years training for the Asian Games, shooting arrows in the summer. In Lebanon people are always saying, “It’s too hot, you’ll get dizzy.” But I’m fine with it.

SAM: So how would you describe yourself in one word?

NZ: Nada? What is Nada? Bah, I don’t like to talk about myself. But I guess, in a word, Nada… tries.