A young man with wide eyes and skinny, aristocratically mod style stages his elaborate suicide again and again. He wants to be missed? Mourned? Reborn? He isn’t convinced he wants to be dead, one supposes, since his flagrant death-performances are never more than just those.

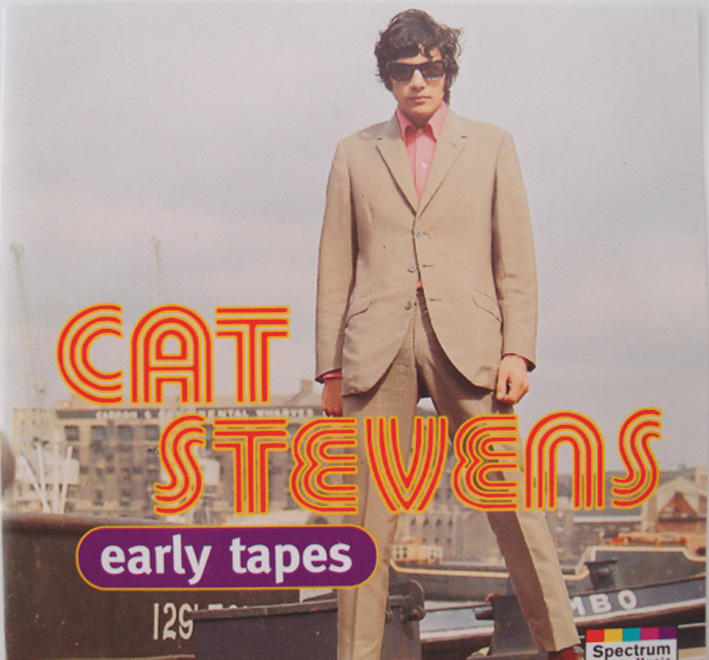

This is the beginning of Hal Ashby’s 1971 film Harold and Maude, the entire soundtrack of which was written and performed by a musician then known as Cat Stevens. Stevens was twenty-three when Harold and Maude hit theaters, making him only a little older than the male title character. But despite Stevens’s youth, he was already a chart-topping force; instead of completing fine art studies, the half-Greek, half-Swedish boy in Britain helped launch the Derum Label at Decca Records alongside David Bowie and the Moody Blues. His simple, relatable lyrics won quick popularity, often addressing themes of searching, as in one track from the film: “Sometimes you have to moan when nothing seems to suit ya / But nevertheless you know you’re locked toward the future / So on and on you go, the seconds tick the time out / There’s so much left to know and I’m on the road to find out.” By the end of 1971 he had released five albums, the last two of which (Tea for the Tillerman and Teaser and the Firecat) would arguably become his most celebrated and inarguably secure him iconic status in the schema of 1960s–1970s pop music.

Like Harold, however, Stevens grappled with the big question that’s usually squat in the center of the road to adult life: What’s the point? The film’s adolescent cynic (played by fantastic Bud Cort) is beset by alienation and neglect. Stevens’s difficulty arose from that other cliché: fame. The dilemma of the young, hit artist writhing in the callous grips of the pop culture machine is stock. Instead of the tragically common escape routes of suicide or crippling drug addiction, Stevens describes a near-drowning off the shores of Malibu as quite literally delivering him from the debauchery of celebrity to the would-be salvation of Islam: “There was no one on this earth who could help me,” he recounted to BBC’s Bob Harris in January 2001. “I did the most instinctive thing — I just called out and said, ‘God, if you save me I’ll work for you,’ and in that moment a wave came from behind me and pushed me forward.”

A year later Stevens’s older brother gave him a copy of the Qur’an, and by the end of 1977 his star ascendancy was entirely forsaken in favor of a new life as Yusuf Islam, devout Muslim. 1978’s Back to Earth LP would be the artist’s last as “Cat Stevens,” and he would in no way promote that release or return to music at large for the next sixteen years.

Despite the abruptness and totality of this renunciation, Yusuf Islam retained the pop idol’s urge to engage an audience. By the mid-eighties he had become something of a poster boy for Islam in Britain, developing Muslim children’s schools and lecturing at universities across the country. One such lecture at Kingston Polytechnic in 1989 kicked off what would prove to be an uphill battle with the mainstream press. His response to a question from a member of the audience (Islam would later surmise that it was a member of the press entrapping him) precipitated a media frenzy alleging that Islam had backed the Ayatollah Khomeini’s condemnation to death of Salman Rushdie in the wake of the Satanic Verses controversy. Islam immediately issued a press release rife with we/they language, stating, “The present attitude of the government and the press is obviously as a result of their opposition to the Islamic legal ruling that Rushdie should be executed and the fact that it has come from a Muslim country.”

If folk/pop’s former golden boy ever truly sought to climb out from under the lens of the microscope, he seems not to have followed through. As testament to Islam’s assumed role as spokesperson for the British Muslim community, he also released a statement the day after the September 11 attacks, expressing his “hope to reflect the feelings of all Muslims and people around the world whose sympathies go out to the victims,” as well as stating, “no right-thinking follower of Islam would condone such an action.” Additionally, VH1 reported that Yusuf Islam would donate all proceeds from his 2001 box set (he maintains creative interest in all Cat Stevens reissues) to 9/11 charities.

Clearly Islam has been willing and able to deploy his renown for the sake of championing the messages of his religion. His official website, yusufislam.org.uk, offers a day-by-day news brief of his travels to receive various humanitarian awards and deliver speeches from Istanbul to Darfur to Abu Dhabi and back to London. This extensive log of philanthropic and religious activity, however thorough, is hard-pressed to outshine the sensationalist coverage of Islam by the western press.

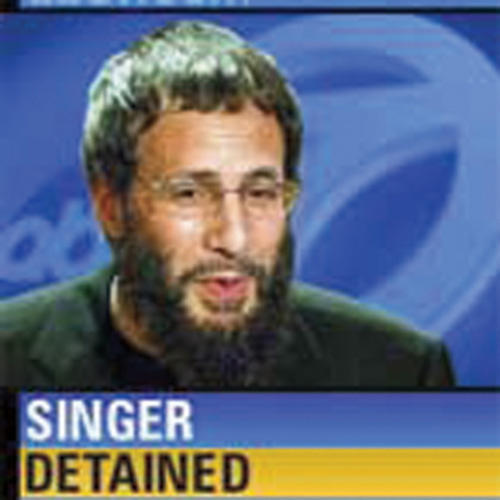

His contentious relationship with the media came to a head in September 2004, when Islam made major headlines as his transAtlantic flight bound for Washington diverted its route to land in Bangor, Maine because his name was flagged on a Homeland Security watchlist. He was separated from his twenty-one-year-old daughter, detained for thirty-three hours, and sent home to England. This was not the first such detention; in 2000 Israeli authorities questioned and deported Islam from Jerusalem — alleging that he had given money to Hamas — but the American incident incited a particularly egregious slew of media coverage.

Again, Islam countered the press by publishing his own accounts of the experience in the mainstream media. In a piece for USA Today in October, 2004, he explained, “The consternation of Muslims living in the West is clearly justified: Islamophobia is not a theory, it’s a fact, and many ordinary Muslims in the UK and elsewhere are suffering, unseen and unheard. Was I just another victim of religious profiling?” The problem here is that he will never know; did the US mistake Yusuf Islam’s identity? Or, as Jon Stewart aptly put it, is the US really suspicious of the man who brought us “Peace Train?” One thing is sure: Despite his early opposition to the amoral trappings of the celebrity bubble, Yusuf Islam now finds himself at the center of a far more precarious world focal point than as a heartthrob doing interviews for Melody Maker magazine.

If the Dixie Chicks were lambasted (CD bonfires in the USA!) for expressing embarrassment that their home state delivered George W. Bush into politics, imagine what would unfold if they were stopped at the British border for suspected terrorist activity? Of course their careers are still deeply entrenched in the industry, while Yusuf Islam instead records exclusively Muslim-themed music on his own label, Mountain of Light. But the fact remains that political hullabaloo is no boon to any famous people, whether or not they openly perpetuate their own fame.

In Yusuf Islam’s case, the media minefield threatens to fence him into the sort of terrifying confusion that he and Harold yearned to escape as young men. Now fifty-seven, Islam still expresses his fraught need to “clear my name of this appalling and baseless slur against my character…In the meantime I am confident that, in the end, common sense and justice will prevail. I’m an optimist, brought up on the belief that if you wait to the end of the story, you get to see the good people live happily ever after.” It is a shame that he must engage in this brand of consternation, even if it is followed by a healthy hokey dose of sanguinity. Instead of being solely a spokesperson for the power of his religion or the importance of humanitarianism, he seems quite often to be a spokesperson for the troubles facing spokespeople. Of course this predicament stems in large part from his status as a well-known Muslim convert living and working in the West, but perhaps it also stems from the nature of his groovy, idealist roots and soulful determination. One has to wonder whether it would have been simpler to just go the way of David Bowie.