Kassel, Kabul, Alexandria

Documenta 13

June 9–September 16, 2012

One could argue that the thirteenth edition of Documenta, the Kassel quinquennial that ran for one hundred days last summer, was the most Bidoun ever. The event was thick with exotic names and hyphenated identities — Hassan Khan, Akram Zaatari, Walid Raad, Etel Adnan, Michael Rakowitz, the Otolith Group, and Anna Boghiguian, among many others — perhaps even more than Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta 11, known in some circles as the “CNN Documenta” for its diversity bona fides and political inflection.

In the years-long run-up to the opening last June, Artistic Director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev was a regular presence in cities close to our hearts. She was there in Beirut. She was there in Kabul. She was there in Cairo. Always with the same kinetic energy, eyes and hair agog, her Blackberry dangling from her neck like a magic amulet. Through that Blackberry, she was in touch with the world. Our world.

Christov-Bakargiev’s Documenta 13 has been justly celebrated — for its boldness and breadth; for its extraordinary series of pocket-sized publications; for its felicitous juxtapositions and its comprehensive examination of trauma. D13’s purposeful international entanglements — the sessions in Afghanistan, the conference in Alexandria, the complicated names — were not scrutinized very closely. After all, what’s not to like about inclusion? Especially against the backdrop of a contemporary art world — the market-driven precincts of it, anyway — that remains a lighter shade of pale. The inclusion of the black, the brown, and the off-white might seem especially welcome for Documenta, founded at a peculiar postwar moment in Germany by Arnold Bode, a purging of Nazi guilt through the return of the repressed.

And yet some inclusions make more sense than others. The essays included here analyze aspects of Documenta 13’s pointed internationalism. Tom Francis considers the larger exhibition and a surprisingly nuanced notion of worldliness at play therein. Clare Davies reports from the “Cairo Seminar in Alexandria,” Egypt, where various aspirations and topographies seemed to go mostly awry. And Sohrab Mohebbi reflects on his trip to the Afghan outpost in Kassel.

Her name is Scarface. She’s a princess — from Bactria, as it happens — but you might not know it to look at her. Her hair is short, parted perfectly in the center, and she has what is properly known as a chin-curtain beard. She is wearing a pleated skirt but above the waist she’s brawny, her torso and arms heavily muscled. And then there’s the scar that runs from her scalp to her chin, bisecting her right cheek. Uncomely features for a princess, you might say.

But then Scarface has lived through hard times — four thousand years’ worth, to be precise — so a little wear and tear is to be expected. She is one of nine Bactrian statuettes that occupy a pair of vitrines in the rotunda of the Fridericianum, the former Hessian state archive that serves as the core exhibition space of Documenta. Scarface and friends are objects of rare beauty. They are small, frangible figurines, chlorite mantles billowing out beneath delicately carved limestone heads. Their faces are neither hyperrealist nor expressionist, but some tranquil, elfin in-between.

More compelling than their look, however, is their function. The princesses are exemplary of a number of historical artifacts displayed alongside contemporary artworks in the “Brain,” as the rotunda space is called. In addition to ancient Afghan figurines, there are the molten remains of sculptures from the National Museum in Beirut, destroyed during Lebanon’s civil war. There’s a group of Giorgio Morandi still-lifes, completed while the artist was living under Fascist rule in Italy in the 1930s and ’40s. And in a vitrine near the princesses you’ll find a painting by Mohammad Yusuf Asefi, the Afghan physician and iconophile who “saved” more than eighty works by Afghan modernists from the wrath of the Taliban by painting over them in watercolor.

One floor up from these remnants of life in distress is a particularly poignant room containing dozens of drawings by the priest and pomologist Korbinian Aigner, who succeeded in cultivating four wholly new apple varieties while interned in the Dachau concentration camp (his creations were named KZ-1, KZ-2, KZ-3, and KZ-4, the KZ short for Konzentrationslager). His apple drawings are juxtaposed with works by Mark Lombardi, an American conceptual artist who depicted the interconnections of the political and financial establishments in America in large-scale sociograms he called “Narrative Structures.” (Lombardi was found hanged in his apartment, an apparent suicide, after an accident at his Williamsburg studio destroyed much of his work.)

Though seemingly disparate, the inclusion of these historical works suggests at least one of the main conceptual moves at the heart of Documenta 13. And though they represent only a small fraction of the art on view, the idea of presenting the historical alongside the contemporary would have been anathema for a major art event even ten years ago. But these artifacts hint at the otherwise obscured philosophy of history set forth by this most historically loaded of contemporary art exhibitions.

Artistic director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev has written of four “conditions” informing her choice of works for Documenta 13 — stage, hope, siege, and retreat. It’s not clear what these conditions tell us about the exhibition as a whole, not least because they cannot all obtain in any single work, historical or contemporary. As regards the historical works in the Brain, for example, no more than two of these conditions — siege and hope — really pertain. But these artifacts are compelling because they transcend the jargon. Where the avant-garde always fixates on the new, reacting to the historical conditions of the present and/or recent past, the objects in the rotunda reveal the elective affinities between artworks and artifacts at a historical remove. The juxtaposition of Aignerian apples and Lombardian social network analysis, for example, uncovers both similar methods (typology) and objectives (oblique resistance).

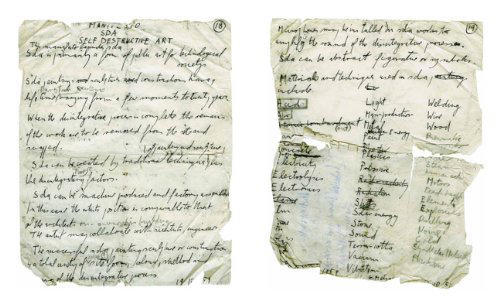

This tells us something about intellectual history — about the constancy of certain ideas, about the recurrence of others. More, it points up the tangential and horizontal moves that history can make. (Vanguardists are necessarily focused on history’s vertical progressions.) Morandi, who painted the same thing over the course of three decades, is commemorated — alongside Dix, Beckmann, Soutine, Brecht, Picasso, and many others who suffered under European fascism — in a text work in Francis Alÿs’s storefront installation, Dedicated to the People of K (K here referring to the comparably traumatized cities of Kassel and Kabul, and also perhaps to the protagonist of Kafka’s The Castle). Mariam Ghani’s film A Brief History of Collapses portrays the parallel histories of the Fridericianum in Kassel and the Darulaman Palace in Kabul — casualties of war that have acquired new functions (as one of Europe’s first public museums and as a war tourism destination, respectively). The rotunda features Rudolf Kaesbach’s neoclassical sculpture Die Ausschauende, last seen in Hitler’s apartment, grouped with Man Ray’s Indestructible Object, a metronome whose arm bears the image of photojournalist Lee Miller’s eyeball, and Miller’s own Vogue magazine exposé on the dictator’s apartment, including her iconic self-portrait in Hitler’s bath. The lesson in all of this, in keeping with Man Ray’s title, is that art — as object, as practice, and as ideal — displays a rare talent for survival.

Documenta aspires to a kind of worldliness. This is most apparent in the establishment of other Positions (read: venues) besides time-honored Kassel: Kabul and Bamiyan in Afghanistan, Alexandria and Cairo in Egypt, Banff in Canada. These initiatives are animated, at least in the case of Afghanistan, by the idea that art might play some therapeutic or salutary role. But these expansions have generated only a few intelligent or purposeful works — Alÿs’s lovely film Reel-Unreel, about children in Kabul; Ghani’s digitization of the Afghan national film archive; Tacita Dean’s chalk drawings of the Hindu Kush (Fatigues). There is a disjuncture between the self-congratulatory rhetoric surrounding these ventures and the impact they are likely to have, either in Kassel, where Documenta-goers can’t help but feel excluded, or in Afghanistan. Unsurprisingly, art interventions are symptomatic of “humanitarian” interventions in general: benefits accrue disproportionately to the outsider-interveners. But we take the bad with the good. For worldliness is not absent at Documenta. To find it, however, does not require a trip to some far-flung Position. Just head to the Fridericianum and make your way into the Brain. Worldliness is there — amid Scarface and her sisters, in the meeting of Morandi and Asefi, Miller and Kaesbach, Lombardi and Aigner. Just give it some time.

—Tom Francis

Waiting to check in at the Grand Royal Hotel in Alexandria, I glanced over at a laptop on the coffee table next to me. The screensaver showed a photograph of a boy, about four years old, holding an enormous machine gun and smiling. The hotel was a tall narrow building with a blue glass exterior and neon lighting, a quiet shabbiness beneath its veneer of luxury. The staff appeared somewhat overwhelmed by the guests, most of them Libyans who had come to Egypt to be treated for ailments incurred during the recent conflict. Single men were sat apart from women and families at breakfast, due to some unfortunate “incidents,” one waiter explained. A few nights later, a male friend and I were cornered in the hotel elevator by a fifteen-year-old who demanded my room number, convinced by my foreign looks that I was a prostitute. His eyes were glassy and bright. A security guard who’d boarded the elevator with us stood mutely by, apparently powerless to do anything. I used my friend as a shield until the young man was dragged out of the elevator by two companions, who apologized on his behalf, laughing nervously. Inside the Grand Royal, a strange world — unacknowledged by those outside and beholden to a different set of rules — appeared to have grown up of its own accord.

A month later, I returned to the city for a weeklong series of events programmed for Documenta 13 by Cairo-based curator Sarah Rifky. The events were off-limits to the public; participation was restricted to those who had been invited to present, as well as students from the MASS Alexandria arts education program and a small group of art-world interlocutors, who served as our designated “chorus.” The proceedings were not without their own tensions; afterward more than one commentator referred to the seminar as “unhinged.” Ludicrously perhaps, the tenor of the event seemed to parallel my earlier experience at the Grand Royal. It struck me at the time as another fraught and claustrophobic microcosm produced, in part, by external forces but seemingly invisible to the rest of the world. A number of factors made for a sense of communal cabin fever, including a demanding schedule of events at sites of historical and cultural interest across the city, the limited size of the core group of participants, and the unrelenting summer heat. Outside, the people of Alexandria went about their lives, oblivious to the seminar’s intense exchanges. Inside, conventions of communication associated with the seminar format gave way to a series of missed opportunities, mistranslations and traded projections.

At times, this appeared merely a matter of miscommunication, well intentioned even, as participants spoke “at” or “through” one another. On the second day, philosopher Suely Rolnik showed up late to her own lecture at the Alexandria Contemporary Art Forum but made up it by apologizing charmingly for being bad at “switching temporalities” — that is, for taking a long time to wake up. She smoked an electric cigarette and delivered an interesting if dense lecture, establishing two possible “destinies” for a politics of desire and peppering her responses to questions from the audience with colorful denunciations of contemporary trends in philosophy and higher education. The discussion set out many of the terms and catchphrases (prominent among them bodily knowing, will to potency, affections, traces of other bodies in our body) that would become something of a refrain over the course of seminar, both in serious discussion and in-jokes about the “bodily knowing dance.” For the remainder of the week, Rolnik and others tended to recode everyone else’s contributions within this very specific vocabulary.

Halfway in, however, this dynamic took a turn for the worse, transformed by preconceived fantasies regarding the nature of contemporary politics, gender-relations, cultural practice, and poverty in Egypt, on the one hand, and fellow participants’ own motivations and frames of reference, on the other. The discussion came to a head in an unpleasant scene involving the students of MASS Alexandria, who had been originally recruited to introduce speakers and provide practical support for the visitors. Students in the audience were surrounded by video cameras, lights, and inquisitive faces; walked through “appropriate” ways of “speaking“ to visitors; grilled for their insights on Egypt’s famous eighteen-day uprising, and given advice on how to understand their experiences. The tone of the seminar remained much the same afterward, as participants demanded aesthetic and intellectual satisfaction from a context that had been deliberately excluded by the very nature of the closed sessions or remained out of reach, given the rather grim mood of the city and the faded institutions that had hosted us. The avowed desire for meaningful communication coupled with the misguided attempts at achieving this aim meant that the event wound up mirroring the tension, fatigue, and hostility of the country’s ongoing “transitional period.”

The original theme of the seminar had been “in a state of hope”: one of four conditions informing Documenta 13’s curatorial approach. But after the election of a member of the Muslim Brotherhood to the presidency a week prior to the start of the seminar, as well as regular outbreaks of violence around the country and the momentum of a by-then obvious counterrevolution, the organizers decided to rethink this approach. Hope was now the domain of the Brotherhood — which, having been outlawed for almost six decades, was now pushing forward a self-styled nahda or renaissance platform. Thus, “sleeping and dreaming” were substituted as the theme of the seminar. The first speaker, Moscow-based philosopher and activist Alexei Penzin, presented a survey of philosophical literature treating sleep, proposing sleep as a site of political subjectivity: “Maybe, instead of grasping this political state of affairs through images or metaphors of a somnolent body or its awakening, we should understand sleep politically and grasp then what is kept beyond all its metaphorical registers?” If the Muslim Brotherhood was promoting Egypt’s reawakening, we in the seminar were in a state of sleep — politically speaking, of course. The actual sleep slept by participants in the misleadingly named Cairo Seminar in Alexandria was fitful.

The change in theme signaled an abandonment of the progress-oriented nature of hope for an embrace of ahistorical disorientation. Another participant, art historian Angela Harutyunyan, saw the shift in seminar themes — and, especially, the shift in locations — as implying, despite itself perhaps, a “resignation and retreat” from the political. “This transition was not simply conceptual,” she wrote in a review some weeks later: “The often political and urban dystopia of Cairo was replaced by the Mediterranean city of Alexandria, where the northwesterly wind would inevitably disperse any political current that would dwell in the same place long enough to threaten to overtake the reality of the art event.” Nevertheless, the art event could not avoid being bracketed by the demands of waking life, which were often more surprising and dreamlike than our week of talks, performances, and screenings.

Back in Cairo, artist and seminar participant Anna Boghiguian was asked to speak at the seminar’s public wrap-up panel. She paused momentarily before delivering a commentary on Alexandria’s particular relationship to hope. Alexandria is a city of glorious renaissances and crushing defeats, she said. (And here I paraphrase from memory as, having descended into a moment of quiet desperation brought on by the unwelcome extension of the seminar, I was caught entirely off guard.) Today, when people smoke cheap, Egyptian-brand Cleopatra cigarettes, they are smoking that promise of Egypt’s renaissance. Those ruins, consumed by tourists or forgotten in plain sight — Pompey’s Pillar, the moldering villas — were sources of resentment, a betrayal that was best redeemed through inhalation, rolled up and smoked with grubby fingers. As I listened, I had the distinct feeling of looking at one of Anna’s drawings of the city with its charcoal vectors, traffic, and museum artifacts, stained with dirty fingerprints and cigarette ash. Perhaps she was suggesting a different model for hope that we’d all overlooked — one that manifests as a kind of violence toward what has already been effectively lost.

Soon after, the new governor of Alexandria — also a member of the Muslim Brotherhood — sent security services to destroy the famous booksellers’ market on El Nabi Daniel Street, frequented by students and those nostalgic for Alexandria’s celebrated “cosmopolitan” golden age. Burning books has not often been understood as a melancholic act. Yet I couldn’t help but wonder if that violence resonated locally in the terms Anna had described. Perhaps those used and yellowing pages represented something many people felt they had once loved or desired but had been taken from them or left to decay before their eyes.

Seminar organizers failed in their attempts to insulate the week’s proceedings from a pervasive sense of unease and antagonism. It’s not clear that it could have been any different, under the circumstances. Until there is evidence of deep-reaching, systemic change, people will continue scratching at, smudging, and running their hands and fingers over this ruined surface. And cultural events will likely continue to be rather dystopic affairs — fantasy-fueled, passive-aggressive, dreamlike — because there seems no way out, with panel participants and lecturers and artists chain-smoking cigarettes as though they could inhale the dirt off all those things they have been forced to forfeit.

—Clare Davies

By the time my companions and I arrived in Kassel, Documenta 13’s main venues were already closed. It was sometime after 6pm, and we had just enough time to duck into the Karlsaue Park, stumble past Robin Kahn’s makeshift refugee camp, and run by the mound of landscaping that made up Song Dong’s Do Nothing Garden — a designated area in which to “do nothing” and where people mostly diddled with their smartphones — before settling in to watch a riveting Euro Cup semifinal between Germany and Italy. A few minutes into the game, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the artistic director of Documenta 13, sat down next to our table in the Orangerie’s bar, sipped a cocktail, and discreetly rooted for the blue team on German turf. (She’s part Italian, after all.)

This iteration of Documenta, dispersed around the city of Kassel and four other satellite sites, featured works by more than two hundred artists, with additional participation from individuals drawn from the worlds of science and academia. In Kassel itself, the exhibition’s central meme was best captured by the “Brain,” a Wunderkammer-ish installation in the rotunda of the Fridericianum, bringing together a curious collection of artifacts, ephemera, and art objects ranging from ancient Bactrian Princesses to Lee Miller’s photographs of Hitler’s Munich apartment. In the Brain, there were also excerpts from the late Egyptian artist Ahmed Basiony’s videos of Tahrir Square, artifacts from Beirut’s National Museum that had been deformed by civil war, Vandy Rattana’s poignantly fantastic photographs of “bomb ponds” in Cambodia, and a Lawrence Weiner text piece obliquely proclaiming MIDDLE OF THE MIDDLE OF THE MIDDLE OF. In its own way, the Brain provided the keys to the exhibition, pointing to the show’s primary threads and themes with pieces drawn from multiple artistic traditions. (It would be disingenuous to cherry-pick favorites here; the Brain, like the exhibition at large, was by no means short of meaningful and moving art works.)

Taking cues from the works assembled in the Brain, sometimes referred to as the exhibition’s “miniature puzzle,” antique binaries such as nature and culture, Orient and Occident, animate and inanimate, art and science, rhizome and arborescence were discarded as obsolete. Everything — as in art and life — seemed to be blended into an organic, timeless mesh that, according to Christov-Bakargiev’s own text available on the D13 website, would have been unattainable given the constipated distance of a critical lens.

You might say “speculative turn” when it comes to this exhibition’s emphasis on reality, and you might be right. And yet, for the most part, the exhibition remained circumspect about its philosophical ambitions. In more ways than one, the show’s spurning of critical theory was actually refreshing, especially after a decade of turgid e-flux announcements and press releases thick with jargon and incomprehensible to both normal people and art-world insiders.

On the first full day of wandering around, we experienced Ryan Gander’s invisible intervention in the Fridericianum’s ventilation system: a steady breeze that blew through the museum as we waited in a long line to see the Brain. After, we ventured upstairs, where one of the most memorable exhibits in the show was on display — a series of apple drawings made by the Bavarian priest and activist Korbinian Aigner, who bred several new varieties while he was imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp. (A juice made from one of Aigner’s apple strains was available for sale at food stands around the exhibition bearing the credit line “concept by Christov-Bakargiev.”) On the second day, we started out from the city’s local commuter train station, the Hauptbanhoff, and watched The Radiant, the Otolith Group’s fascinating video on the necropolitics of post-Fukushima-nuclear-meltdown Japan, before moving on to the Ottoneum, Germany’s first theater building, now a natural history museum. It was on the way to Tacita Dean’s installation in a former tax office (delicate ephemeral chalk drawings of mountains of Afghanistan, secured from erasure by strict law enforcement) that we walked into Oberste Gasse, a former army hospital-turned-Chinese restaurant-turned-temporary Documenta venue.

One entered the exhibition space, which I first mistook for a decommissioned water closet, through a tiled entrance tattooed with Sharpies. (Later I learned this was once the restaurant’s kitchen.) I consulted the guidebook to realize that what I had just walked into was a gallery dedicated to works by Afghan artists, or rather Afghanistan (as it included works by a few non-Afghan artists who had worked, or lead workshops in that country). The graffiti kitchen, it turned out, was an artwork by the artist Abul Qasem Foushanji. It turned out that, in addition to its main campus in Kassel, Documenta 13 had annexed sites in Egypt, Canada, and Afghanistan (an unlikely trio, you might say). But the Afghans ended up clustered together in this demilitarized hospital. Here, the ceilings were low, the lighting was dim, and the works were choreographed and installed in such a way that they appeared at first glance to constitute a solo presentation. If there had been more places to sit, the whole thing could have easily passed for a slightly upscale ethnic restaurant. Unlike Venice, Documenta has never been structured around national pavilions, so walking into one was particularly awkward. The space, which was quickly nicknamed the “Afghan Ghetto” — an appellation that, according to one eyewitness’s testimony, induced a heated exchange between Christov-Bakargiev and one of her curatorial “agents” during a public seminar staged in the Ständehaus during the exhibition’s opening week — managed to reinstitute all the tired representational clichés and cultural hierarchies that practitioners across the field of contemporary art (and other fields) have spent years trying to dismantle.

The installation, in its strange insistence on this critical mass, seemed to imply that Afghan artists can only speak in soliloquy. The grouping seemed to communicate, too, that these artists cannot possibly possess the artistic merits the rest of the Documenta participants, spread out as they are, do. Rather, they are hung side by side with a slideshow drawn from a Kabul digital photography workshop (a perfectly important project in and of itself, initiated by artist Masood Kamandy). Even works such as Jeanno Gaussi’s Family Stories, where the Afghan-born German artist commissioned the Kabul-based sign painter Ustad Sharif Amin to paint thirty images drawn from her family album before their immigration to Germany, were not offered a prominent space outside of the designated Afghan area. Yet it was Mexico City–based Mario Garcia Torres’s work on the first floor of the Fridericianum, the crème de la crème of all Documenta venues, that first introduced viewers to the exhibition’s persistent Afghan trope. Have You Ever Seen the Show? (2010), Garcia Torres’s poetic Chris Markeresque photo essay, chronicles the artist’s search for the late artist Alighiero Boetti’s now-mythic One Hotel in Kabul (see Bidoun #19). And as Boetti is one of the artistic director’s guiding lights through this Documenta journey, we visit Afghanistan via the personal experience of an Italian artist, a classic metonym for anthropological praxis.

In Kassel, Afghanistan — a country at war for three decades, ravaged by internal conflicts and foreign interventions of all kinds — is used as a prop, pointing to one of the artistic director’s four self-proclaimed “states of mind.” As such, Afghanistan in the world of D13 illustrated the state of being “under siege,” as described in this bullet point in the exhibition’s curatorial statement: “Under siege. I am encircled by the other, besieged by others.” The other three states of mind include “on stage (Kassel), in a state of hope (Egypt), on retreat (Banff, Canada).” Yes, and under siege Afghanistan is — but so is Syria, Tibet, Congo, Sudan, Yemen… . None of these places, however, had the distinction of occupying their own D13 venue. Why, you might ask, should one bother looking so far east? Or should Afghanistan shoulder the burden of representing all that is messed up in this world? In the mounds of essays and reviews on the subject of Documenta, most of them laudatory, not enough has been written about this peculiar section of the show.

It would no doubt be naive to suppose that the exhibition’s organizers were unaware of the problematics of such an approach. One could easily summon up potential theoretical arguments or philanthropic impulses behind the Afghan endeavor. When it comes to the former, it seemed that the exhibition aimed for a meta position, or a post-post position as one curator friend put it, with an argument along the lines of: If postcolonialism is forever ontologically Eurocentric with its institutional and discursive roots, and anticolonialism is too radical or derailed by extremism, this position is unburdened by ontological shackles and simply levels the uneven playing field of culture. As such, the sheer force of imagination and creativity, artistic or otherwise, brings Homo sapiens together with no hierarchies between place, person, and discipline. But then what justifies this discrimination between various creative outputs? Why in Kassel can we sit through lectures by heavyweights like Boris Groys and W.J.T. Mitchell (the list is thrilling) while the Afghan sessions offered workshops and presentations such as “Perspectives on the Art of Today,” or “Creating an Art Magazine: Testing the Grounds/Finding the Language”? Why couldn’t the so-called Afghan Ghetto enjoy the same breadth and space or the same high level of thought and sophistication that went into “the Brain”?

At the same time, the instinct to explore this Afghan state of mind may have been, not unlike a cultural NGO’s MO, imbued with a humanitarian motivation. A gesture of cultural diplomacy, Documenta 13, whose reported budget of more than 25 million euros hails from the German government, could count as a uniquely German contribution to Afghanistan’s nation-building in-progress.

Back at home in Los Angeles, I watched Letter to Jane (1972), the Dziga Vertov Group’s meditation on a single photograph born of Jane Fonda’s 1972 visit to Hanoi. Exploring the role of the intellectual in the struggle, the film analyzes the composition of the photograph, Fonda’s position in the frame vis-à-vis the Vietnamese, her facial expression and posture, and its presentation in the new global media. The filmmakers, Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, question Fonda’s motivations in visiting the country and posing for the camera. Then they self-reflexively ask whether “we risk doing them more harm than good by providing a good conscience for ourselves in such a cheap way.” Visiting Afghanistan via Kassel some forty years later, the question remains an urgent one.

—Sohrab Mohebbi