Iranian visual artists have fallen into a coma. After a decade of relative openness, we’re unclear about our future, thanks to the arrival of a new administration and attendant changes in artistic policies-and, indeed, aesthetic outlook.

All around us, arts spaces are closing. The resignation of Mohammad Mehdi Asgarpour as head of the Cultural-Artistic Organization of the Tehran Municipality was devastating to artists who had relied on his financial support for larger, more innovative public projects. Likewise, the August 2007 resignation of Behrouz Gharibpour, who headed a semi-independent downtown venue for artists called the Iranian Artists’ Forum, further complicated matters, for he was among the last bastions of reformist thinking within the establishment. Since the new administration has been in place, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMCA) — which serves as the principal artistic venue in the country, as well as the architect of most policy for the visual arts-has moved away from contemporary work, holding exhibits titled “The Art of Resistance” (which featured an enormous banner bearing the face of Hassan Nasrallah at the museum entrance), “The Art of Islamic Calligraphy and Gilding,” “Flight and Endurance,” and “Costume Design.”

Against this charged and changed backdrop, it may be helpful to map the scene by dividing Iranian artists into three general categories. There are those who, religious or not, come under the protection of the state. They often participate in exhibits organized by the TMCA and are regularly sent abroad as privileged official Iranian representatives in biennials and the like. A second group of artists have established themselves outside of the official system. They typically create paintings and sculptures that are more or less innocuous, often decorative. These artists have managed to do well in the local art market and, in most cases, have continued producing and selling their works unabated in the posher galleries around town, as well as at auctions in Dubai.

A third group — and this is the group that I want to focus on-is made up of mostly younger artists who, given the increasingly global nature of the art world, have been trying to position themselves within an international market. With the advent of the new administration, this third group tends to be deprived of government assistance in the form of access to venues, access to materials, and simple moral support. Members of this third group tend to show their works in lesser-known galleries and to limited circles of friends and buyers. Still, many among this group have shown their work to foreign curators. The more successful among them have shown their work outside the country.

But engaging with the international art market is itself a fraught process. More often than not, artists of the third group are invited to take part in group cultural shows, under the banner of Iranian Contemporary Art. As such, they may occasionally feel the urge to present their work within the framework of grand narratives of liberation or some sort of exotic political commentary.

Along with a proliferation of such cultural shows, there have been a number of workshops bringing European artists to Iran in recent months, with a stated aim of providing a platform for exchange-a worthy enough goal. But like the group shows in Berlin and Paris and so on, these encounters have also been loaded, particularly given the position the West occupies in Iranian arts education, with our art history books, for the most part, European in orientation. Intellectual discussions within the community are too often measured against a Western yardstick that doesn’t necessarily correspond with the realities of the visual arts in Iran or our particular traditions. When a project originates in the West, its merit is rarely questioned.

Herein begin the double standards that we must all come to terms with. Faced with increasingly limited opportunities in the official realm, and at the same time, with a mounting Western appetite for the ethnic, we have had to contend with the following question: Should we try to curry favor with the tastes of the Western curator, or await the day the TMCA falls under more favorable leadership?

In the past I’ve suggested that the third group ought to resist the lure of the exotic, that we must continue to present our work in a manner that is faithful to independent thought. We should collaborate, support each other, buy one another’s work. In the past year and a half, there have been a number of hopeful signs. Several meetings took place in which artists came together to join forces. Some of these meetings were held at Azad Art Gallery, others at artists’ private studios. At least one collective studio was established in this time, called Side Effects. Still, this spirit of solidarity didn’t last long.

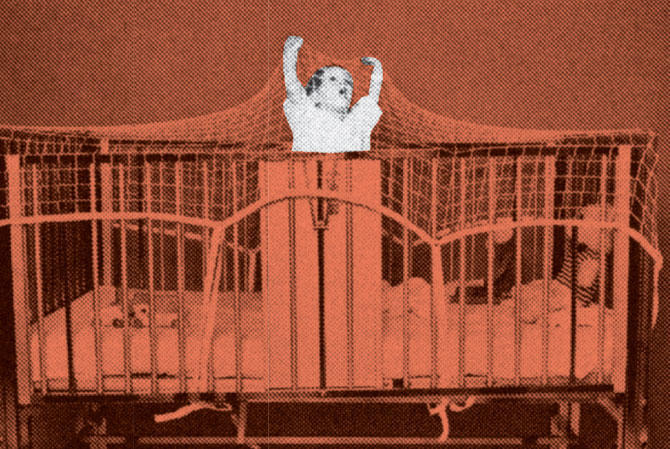

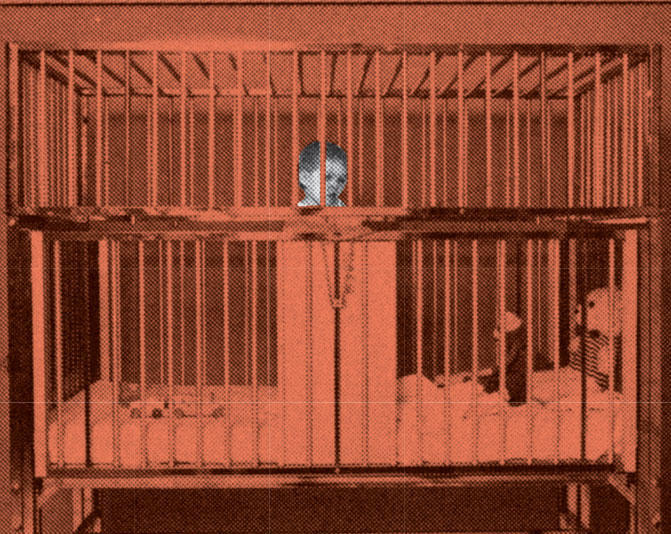

An analogy to the country’s reform movement may be useful here. Iran’s golden age of political reform spanned the eight years of Mohammad Khatami’s presidency. But that period ended, in part due to the inability of the reform movement to form a united front. Finding it useless to blame their woes on the totalitarian nature of the state, reformists started pointing fingers at each other, leading to factionalism within their ranks. Likewise, this generation of third-group artists has similarly frozen in the face of the obstacles before them. We implode, break down, and, much like a scorpion facing danger, sting ourselves.

Eventually, Azad Gallery meetings diminished in frequency, Side Effects shut down without so much as leaving an aftertaste, and artists of the third group are again depending on the hope of a connection to the outside market. Today it’s more important than ever for us to support one another, to resist neat narratives of victimization and pat understandings of what it means to be an Iranian artist. In short, what we, the third group, need is a third way — an approach that is born of this particular moment and that, in the end, is distinctly ours.