Hamid’s the quiet one. “Crazy!” laughs his manager, a fidgety Marrakechi who’s as animated as Hamid is still. “He spent a year walking around Morocco. Walking! Just him and his guembri, from village to village… Don’t let him fool you — his hair is gray! He dyed it for this tour.” Lean, dark-haired (now), and gifted with a snaggletoothed grin, Hamid Batma could be in his thirties or his fifties. The music he performs has a similar timelessness, based on shifting and accelerating rhythms learned by the body, through habit. Unwritten.

Like most Gnawas, Hamid enters a kind of trance when he plays. Unlike most, he never seems to fully exit from it. We toured Europe together in October 2004 and again in 2005, my band Nettle and his band Nass el Ghiwane. Ramadan in the UK made him go nocturnal. I remember Hamid glued to his hotel-room TV, giggling quietly, transfixed by the dismal late-night programming of Britain, not a word of which he could understand. Greasy halal takeout competed with boxed orange juice and cigarettes for table space.

The rest of the band would joke about him being a nomad type, a weirdo, a few clicks away from a total dropout. So far as I could tell, Hamid never bothered to explain anything. Onstage, when the others wore ordinary clothes, he preferred a crisp djellaba.

My most vivid experience of Hamid Batma occurred after a free concert in Brussels. About three thousand people were gathered. White Belgium had never seen the Moroccan community manifest itself like this; by the third song, people were throwing their children into the air. Fans clamored to get backstage the moment it ended. Every so often, someone would talk his or her way past security, run inside, and start kissing everybody. It took nearly an hour to get out of there.

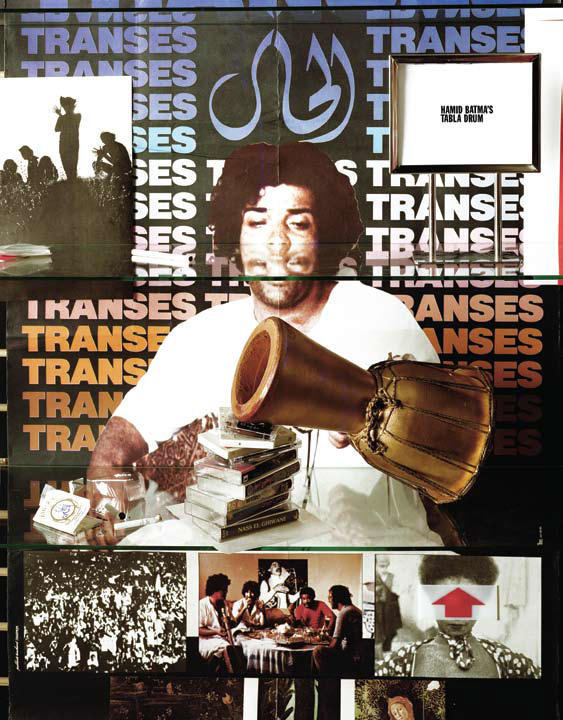

Driving back to the hotel, someone’s loose cigarette was on the verge of ashing. “Wait,” Hamid said, reaching for a tabla, which he turned upside down and proffered as an ashtray. I was shocked and looked it. He was surprised by my reaction, but I couldn’t get over the fact that a musician was treating the floor of the van better than he treated his instrument.

Three years later I watched this same sublime disregard repeated on restored celluloid. In Transes, a poetic 1981 documentary about Nass el Ghiwane, Larbi Batma — the band’s humble front man, Hamid’s older brother — rolls himself a cigarette and proceeds to tap the ashes onto the head of his tabla. Knowing their music as I do, and the way it reverberated across a country (and does still), this simple act exploded with meaning.

As musicians, Nass el Ghiwane disregard virtuosity. Virtuosity implies mastery focused by unity of purpose — what we mean when we speak of someone becoming one with his instrument. (Allal Yalla, the group’s banjo player, is actually a virtuoso; I have yet to hear anyone else play that instrument with such precision and intricacy, in the 1970s or now. But the band as a collective eschews it.) They work in an adjacent space, that of familiarity, beside or beyond virtuosity, in which one’s instrument is no longer necessarily an instrument. A drum becomes a table, an ashtray, an extra limb. The percussion of the Batma brothers is by turns magical and mundane; rather, it is both at the same time. The tabla’s drumness diffuses into the ambience of daily life, and the songs whose heartbeat they provide live inside people in the same way.

Larbi Batma died of lung cancer in 1998. By that point, the band’s fame was such that King Hassan II took him into his private care, but even the best doctors at the royal hospital in Rabat couldn’t undo what a lifetime of cigarettes had done. Hamid joined Nass el Ghiwane a year or two later, to keep it alive.

In Paris recently, weaving my way between skinny Arab boys selling contraband cigarettes in the streets around the Barbes metro (one of those open-border Maghrebi microstates in tentative European bloom), I discovered that the shops no longer stock Nass el Ghiwane cassettes. In previous years I could always find tapes with covers I didn’t recognize. Since the compilations were so haphazard, tunes I hadn’t heard would often surface. Virtually all of those recordings were bootlegs, many of them little more than personal mix tapes.

If you ask around, though, you can still find their music, now on shaky CD-R copies. The selection is smaller, but it’s there. Nass el Ghiwane remain the most versioned group in and from Morocco. (Algerian raï star Khaled got his start in an NEG cover band, and thirty years later the phenomenon persists.) The group practically invented Moroccan pop music — and, at the same time, inspired the music-piracy industry. They’ve never earned much money from record sales; the digital-era “crisis” of our contemporary music industry is ancient news to these pioneering victims of modern bootlegging.

Nowadays the songs seem to belong to everyone. They’re so well known, so beloved, that you almost take them for granted. The songs are everywhere and nowhere, forming part of the fabric of everyday life in Morocco. While the music of Nass el Ghiwane is steeped in poetry and history, everything that surrounds it remains earthy, intimate to the senses. Priceless, and worthless, as any old drum.