In 2003–4, British artists Rosalind Nashashibi and Catherine Yass spent time in Palestine and Israel, making films for exhibition this year. Best known for winning the Beck’s Futures award in 2003, Nashashibi made Hreash House, a film that is confined to the domestic interior of a Palestinian home in Israel during Ramadan. It has been shown at CCA, Glasgow, and at Tate Britain, London. Yass, who was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2002, chose to film the façade of Israel’s ‘separation barrier.’ Her film Wall will be shown in a solo show at Alison Jacques Gallery, London, this autumn and at Herzliya Museum of Art, Israel, in 2005. Commissioned by Bidoun, the two artists got together upon their return to compare notes. Over many hours of discussion, key questions arose — about working in Israel and Palestine; about the complex relationship between art and politics; about the nature of visual language and its potential to create contemplative space and time.

Catherine Yass: I got in touch with you because I felt the film I was making should exist within a context of discussion—in a way it’s there to generate debate. From seeing your film District of the Post Office, of the kids hanging around, I understood that it was both about Palestine and about filmmaking. That balance is something you don’t often see and it’s something I’m also trying to deal with.

Rosalind Nashashibi: There seem to be some similarities about the way we approach both the subject and filmmaking in general; for me, this kind of approach gives the viewer a space to react, through showing rather than explaining or interpreting.

CY: I think it’s about trying to find a way of giving the subject an openness for people to enter in and a space to think for themselves. In your film [Dahiet al Bareed (The District of the Post Office)] you set certain conditions when you filmed those people. You chose a few places and you left the camera and let them do their thing in front of it. And in a way I was doing something similar. I set up the camera to travel along the wall in a single direction. But even in creating a framework for things to happen in, you’re still the person setting the conditions.

RN: Absolutely, yeah.

CY: So, I suppose we allow a process its own momentum but within conditions set by us, so there’s a play between the choices that you make and what you allow to happen which you don’t control.

RN: And of course the editing suite. What stays and what goes. I guess we both approach films kind of knowing that something is interesting, knowing that you want to film but not necessarily knowing what associations you want to find or make, until you’ve actually gone and shot some film. Decisions come later watching the footage in the edit suite; they still seem like non-decisions but are really the decisions. Filming is an intensely connected experience of time, all about performance of the physical thing and the nervous thing of the shoot. At the time of filming, there are so many questions that go through my head; but I don’t choose to answer them at that stage — it’s a more intuitive process.

CY: For me it was slightly different as I planned the filming first and it was determined by the length of each section of wall. But I still had to order the sections and choose which shots to use. And unpredictable things happen while you’re filming. It wasn’t until I actually filmed the wall that I realised that it [the wall] was something to do with me and my response to it that I just had to explore.

RN: It’s only from actually making the film that it begins to exist in its own right and tell you what it’s all about.

CY: Yes, and I think that when you’re dealing with something this political it rings hollow unless you really do have a reason, and that’s somehow embedded in you; you may not know exactly why but it’s really personal.

RN: Had you been wanting to do something in Israel/Palestine before or was it the fact of this wall that prompted you to make this work?

CY: WelI, I never wanted to be labelled as a Jewish artist or make work directly about being Jewish because I felt I’m equally brought up in London and it forms part of my background in the same way that lots of other things do.

RN: Yes, it doesn’t have to be remarked upon every time within your work. I’m half Palestinian and it is part of my life and who I am, but I was born and have lived all my life in Britain, and I am interested in other things and make work in other places.

CY: Exactly. But then I got invited to go to Israel to do some research. When I went initially there was no obligation and I thought, what am I getting into here? It was only when I saw the wall that I thought I cannot ignore this, I have to make this piece of work.

RN: As if you have no choice in a way. I think there could be a point at which you might choose not to — it’s a commitment and it does alter things, not only for you but for how you are seen.

CY: And it also impacts on how your past and future work will be read.

RN: But in the end the actual facts of the thing that you find, that you want to make a film about, sort of take away that choice.

CY: What made you want to go there?

RN: Well, I used to go as a child up until I was about seven years old, to where my father grew up, in this area called Dahiet al Bareed (District of the Post Office), conceived and built by my grandfather who ran the Palestinian Post Office. It was a kind of utopia in a way because they ran and owned their own neighborhood where everybody knew each other. I thought, well, I’ll go there and find out what’s happened to that place now. I found it to be surrounded by this kind of sprawl and for various political reasons to do with people being urged to move out of the Old City and coming in from other parts of the West Bank, it had turned into this quite chaotic, very quickly built-up, quite squalid area, where there was no real rule — a kind of no-man’s land. It is technically West Bank but it has never been under the control of the Palestinian Authority — it’s under the administrative division of the Israeli military. Nobody was really looking after the place so the kids seemed to be ruling the streets. A place defined by the checkpoint down the road and its position as neither Occupied Territory nor the West Bank.

CY: I filmed the wall from the Israeli side as that’s closer to my background, but I concentrated on the sections which cut through Israeli Arab and Palestinian communities which, like the District of the Post Office are in a kind of no-man’s land. I think it’s significant that I couldn’t get insurance for filming in some of these places since they don’t fit into any official territory. These areas are also where the wall is at its most brutal — where it passes Jewish communities it’s softened by using more domestic-looking blocks, and in the countryside it’s usually a fence.

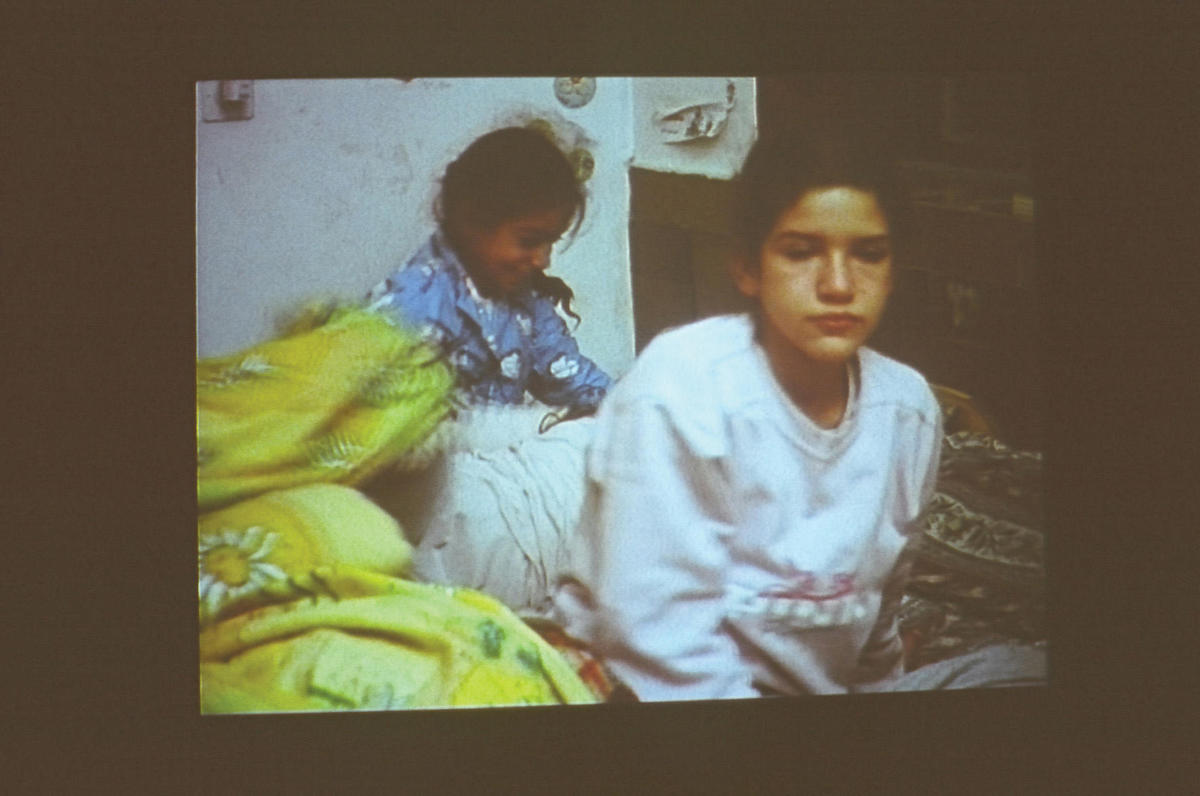

RN: In that space which is no-position or no-man’s land there are so many shifting possibilities that should encourage people to be active in the reading of the work. This kind of no-place was also important for my film Hreash House. The house is in Nazareth, which has a totally Palestinian population but is in Israel proper. The Hreash family are one of these extended family groups all living together in one single apartment block. I tend to look more at the familiar rather than the more spectacular aspect. I don’t think your work is spectacular but it’s looking right into the heart of the fact of the wall.

CY: My film doesn’t have people in it — it’s just got this really horrible structure. I’m interested in the difficulty of making an image of something that is so damaging but blank at the same time. I’ve filmed the wall in such a way that it fills the screen, leaving a really narrow margin at the top and bottom so you can just see the occasional building or minaret behind it. So you get a glimpse of something on the other side but you can’t really see it. The film enacts what the wall does which is make the viewer’s own view restricted. It’s quite a tough film to watch because it really does make you feel imprisoned.

RN: It’s an aggression on the viewer in a way.

CY: Yeah, and what I find really difficult about filming it is that most political art that I’ve seen that’s affected me, if I think of someone like Goya, it’s from the point of view of the people who are affected — and that’s what you’re filming. I’m filming the thing that’s doing the oppressing. It’s very difficult suddenly not to aestheticize, because actually the wall is built with these modernist-looking concrete blocks, which could resemble a Richard Serra sculpture. They can start to look quite beautiful — that’s really frightening.

RN: And it’s a reminder of what went on in the twentieth century; it can’t help being linked to Modernism. You can’t disconnect that visual language from its political manifestations.

CY: We are in a very privileged position in the West where if you draw a line across a piece of paper you can discuss what it divides and the ethics of drawing a line. You can discuss things in an abstract way. Bruce Nauman, for example, makes most of his work in his studio and within that space he can ask a lot of questions and they can be ethical, they can be about whether he’s on one side of the line or another. We’ve taken questions like that but they’re in a very real situation. I think the point of those ethical questions is that they should eventually equip you in some way to address things in the real world. So, I think we’re caught in a strange situation between very real, emotional people’s lives and politics, and the more rarefied place where you can try out ethical questions.

RN: I think that’s it the studio is a safe place to question and play with ideas. It’s more dangerous in some ways in terms of how things can be read, to take it out into the real world. It does require a different approach. I think it’s telling that we both choose not to put ourselves in the work.

CY: And Hreash House is about aspects of people’s lives, but also ethical issues like where you put the frame, where you put the lines. The decisions that we make as artists are political in the same way that decisions about where to build houses are.

RN: The reason I wanted to restrict the film to the four walls of the house — you only ever see the inside or the façade — was because I felt that the home was the only place that you could really feel safe. Even if there was no immediate physical danger outside the house there was this uncertain feeling, this unknown pernicious situation, a constant worry to do with where you are and who you are.

CY: There’s a similarity in both our approaches, that the view is limited and that we are both referencing these restrictive conditions in the way we film and frame each shot.

RN: It’s questioning the form and putting it to use…

CY: I think that’s where time is very important. In Hreash House there is time to sit there and look at the activity going on.

RN: In time you grow accustomed as well don’t you? You begin to see the structure of the activity.

CY: And I’ve filmed the wall going on and on, and it doesn’t seem to get shocking until you realise it’s going on far too long for a narrative structure. The length of time adds to a feeling of dumbness that the wall has. It kind of shuts out other stuff and shuts you up. For both of us, I think the work is sculptural and spatial as well as temporal.

Another thing is where you exhibit. I’ve been asked to show Wall at Herzliya Museum of Art and I know that a lot of people, including friends in Israel, think I should boycott it. I wouldn’t show other work there at this time, but I’ve decided to show this film because a lot of people in Israel have never been to the wall or seen it. And Herzliya Museum has a history of showing work critical of Israel and I think it’s essential to support that and acknowledge that there is opposition inside Israel. As a Jew I need to separate myself from Israeli policy. I know some people believe that criticism of Israel will lead to anti-Semitism, but if there’s no difference voiced, no one will know that a large number of Jews criticise Israeli policy, and anti-Zionism will be conflated with anti-Semitism.

RN: It’s significant that we are both not only working with the ideas about the situation in Palestine and Israel, but also elsewhere, and that the experience of the Israelis and Palestinians should not be separated from the rest of the world. Seeing these works within our whole bodies of work gives what we are doing a context.

CY: When I’ve made work in London, like my film Descent, the politics of it are more hidden. People can recognise the subtle things going on and they don’t see it as being from a particular side. The politics don’t even have to be consciously recognised, they are just there in it. As soon as you make work outside a culture people are very familiar with, there’s a loss of confidence in reading the work and a desire to simplify things and look for answers.

RN: If you show anyone with a headdress on or an Arab-looking man or woman, people think it looks like the news.

CY: So do you think that one role of the artist is to undo the news?

RN: Yes, certainly, to re-look at things and question accepted ways of seeing. I tried to articulate this in my film The States of Things — a three-minute, 16 mm film of a jumble sale in black and white, which I processed myself so it looks kind of crunchy and a bit dirty and you’re not quite sure when it was filmed. It’s just people rummaging through stuff at a Salvation Army jumble sale in Glasgow, but I used this Umm Kulthoum soundtrack, a classic Egyptian love song from the 1920s. The viewers read the scene as being Arab, Indian or finally from somewhere in Eastern Europe, but not as themselves in their own city.

I was angry at the time about the idea of ‘East / West,’ a stupid, black-and-white definition, and the exoticizing of ‘East’ which denies its shifting, relevant, human existence. I wanted to show more of the greyness and the muddledness of actual individual experience. As a half-Palestinian and half-Northern Irish artist, brought up in England, now living in Scotland, it’s not clear cut but who is clear cut? Without that ambiguity there is no position. Without it the viewer can’t approach the work and there can potentially be a shutting off or expectation of how you’re going to feel about the piece. Because of the way this material is presented in the media you need some distance, and I think that ambiguity provides that distance.

This is an extract from conversations recorded in London in July/August 2004, edited by Antonia Carver, Rosalind Nashashibi and Catherine Yass. Rosalind Nashashibi’s solo show ‘Over In’ is at Kunsthalle Basel, September 19–November 7, and she is undertaking a Scottish Arts Council residency in New York from November 2004 to May 2005. Dahiet Al Bareed (District of the Post Office) is included in ‘Expander,’ Royal Academy of Arts at Burlington Gardens, London, October 16-24, 2004. Catherine Yass’s film Wall will be exhibited in London at Alison Jacques Gallery, November 18-December 23, 2004, and at Herzliya Museum, Israel, June–October 2005. It will be included in the touring exhibition ‘Territories’ (www.konsthall.malmo.se.oas.funcform.se/o.o.i.s/2426).