Islam and the West: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida

By Mustapha Chérif

Translated from French by Teresa Lavender Fagan

University of Chicago Press, 2008

In the spring of 2003, Mustapha Chérif and Jacques Derrida sat down in Paris’s Institut du Monde Arabe and disagreed. Derrida had come directly from the hospital, having just been diagnosed with the pancreatic cancer that would kill him fifteen months later. Upon arriving he specified that “for anything else I would not have come.“

Chérif and Derrida’s discussion concluded a conference on relations between France and Algeria. There were excellent professional reasons for Derrida to have been invited, and excellent personal ones for him to have come. Over the course of the preceding decade, Derrida had increasingly turned to explicitly ethical questions of reconciliation, pardon, amnesty, and hospitality. The personal reasons related to Chérif and Derrida’s shared homeland, Algeria, and what Derrida had taken to calling his “nostalgeria.”

Islam and the West: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida is less the record of that event than a reflection on it. Instead of reproducing the discussion that was of such importance to Derrida, Chérif chose to replace his part of the conversation with what he “wanted to say,” “was trying to say,” “endeavored to express,” “attempted to explain,” “had been thinking,” and so on, while leaving Derrida’s responses tel quel. In every case, the reader can more or less make out what Chérif must have asked Derrida, but his lengthy asides interrupt any sense of “conversation.” In an apparent attempt to re-inject a sense of the event, he offers a smattering of narrative details, from how he felt when he saw the full auditorium (“I was immediately struck by how many impressive people were in the audience”) to how Derrida interacted with him (“He looked at me warmly,” “He responded gently, but firmly,” “He said to me with a mix of humility and vehemence”). Chérif’s choice of form — a hybrid of transcript and memoir — seems all the stranger given that his positions find such ample expression elsewhere in the book, in not one but two introductions, as well as in a conclusion and an appendix. (The English translation includes an additional introduction by Giovanna Borradori, making the structure of the book still more like a set of Russian nesting dolls, with a diminutive Derrida at the center.)

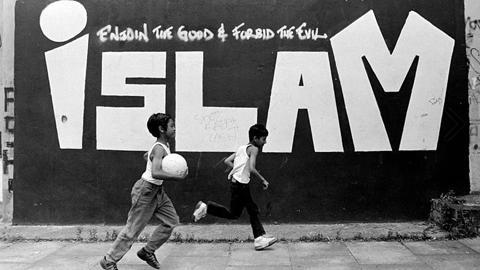

While Chérif’s manner of recounting this encounter tends to blur its contours, it does not efface all signs of their disagreement. Both as a scholar (he is a respected specialist on Islam and philosophy) and a politician (he has served both as an ambassador and as Algeria’s Minister of Education), Chérif’s goal, whether in conversation with Derrida or with Pope Benedict XVI, has been to check two sorts of excesses. On the one hand, he wants to combat the stereotypes of those in the West who see Muslims as practicing a religion whose essence is intolerance, which is misogynistic, xenophobic, anti-rational, pre-modern, and, at its core, violent. On the other hand, he wants to check the influence of those in the Muslim world so consumed by resentment, so angered by betrayal, or so blinded by faith, that they fall into fanaticism, practicing and preaching intolerance at times and in places where that intolerance leads directly to bloodshed. Chérif is the author of Islam: Tolerant or Intolerant? (2006) and has argued again and again for, well, tolerance.

That said, he does not argue for a secular society, either for his native Algeria or elsewhere in the Muslim world. Reason untempered by religion is something he sees leading to a devastating “de-signification of the world,” one that shakes “the foundations of humanity as it has existed since Abraham.” In its stead he advocates the “reasonable reason” he finds invoked, as he recalls for this readers, more than forty-five times in the Qur’an.

Derrida, however, had a different vision of reason and secularization. “I think that we must,” Derrida said, “consider as our primary task to ally ourselves with those elements in the Muslim and Arab world that are working to further the secularization of politics,” to which he added, “and to do so through and out of respect not only for the political realm and democracy, but also through and out of respect for faith and religion.”

The discussion between the two men does not, however, fall into the well-trodden path of faith versus reason, Islam versus Enlightenment. Derrida’s is indeed not the “reasonable reason” of the Qur’an, but it is also not a pure reason that would light up every darkness. Reason and knowledge are of paramount importance, he stresses, but they also have limits — and what lies beyond those limits is something a lot like faith. For him, reason, however reasonable, will never be able to provide us with a guide wherein each rational cause and effect can be calculated in advance. “If we simply knew what to do,” he says, “if knowledge could simply guide our actions, then there would be no real responsibility.” A responsibility worthy of the name involves a risk that can as little be covered by following the tenets of reason as by adhering to the dictates of religion. As a result, it always involves what he calls “a leap of faith.”

This play on words is more than mere play and points to the other point of disagreement between the two thinkers — a disagreement about the meaning of faith and its independence from religion. Chérif and Derrida have no trouble agreeing on the importance of tolerance, openness, patience, and courage, just as they have no trouble agreeing in their denunciation of the Bush administration and the fanaticism it has fueled. But they do disagree about the relation between faith and religion. Chérif is willing to go far in his positions, but not to the point where Derrida stands. Replying to Chérif’s concern that secularization will lead to a “de-signification of the world,” Derrida remarks that, “I don’t think there is any contradiction between political secularization and what you call life’s mystery.”

The line Chérif walks between secularism and a sense for life’s mystery is a fine one; it frequently leads him to choose airy declarations of the importance of openness over a sharpening of the points under discussion. His clearest, and nicest, touch, however, is one he saves for last. The cover of the French edition of Islam and the West shows Brueghel’s painting The Tower of Babel, presumably as a subtle gloss on Chérif’s parting words: “May the wheel of time not close us in, may the wheel of worldliness not crush our differences, may we not forget what is needed of us. For this to come about we must foster a shared awareness that the other, different from us, is indispensable to our lives. ‘If God had wished, he would have made of you one community. But what he wished,’ says the Qur’an, ‘was to test you through the gift of difference.’”

The English translator has a hard time with this final paragraph. The ensuing awkwardness is understandable; less understandable is the quotation from the Qur’an. French citation practices being different from English ones, the he said, she said, the Qur’an says, when they occur in the middle of a French sentence, are left inside the quotation marks (“Please, he said, translate this correctly” instead of “Please,” he said, “translate this correctly”). The English edition curiously fails to render this, leaving the reader with the impression that Chérif is quoting some unnamed person paraphrasing the Qur’an. But he is, of course, doing what he says: quoting the Qur’an. The passage in question (5:48) can be rendered as, “If Allah had so willed, He would have made you a single people, but (His plan is) to test you in what He hath given you” (Yusuf Ali).

Chérif chooses to call this unnamed thing through which God tests us “the gift of difference,” and thereby gracefully names the two central terms of Derrida’s late philosophy, “gift” and “difference.” In place, then, of the notion that difference exists, that it is a burden and a problem, Chérif emphasizes an idea that is at once more reasonable and more mysterious — that our differences are the most precious gift we possess.