In 1382, glory descended upon the young men of England’s seminaries and theological schools, alongside such novelties as mystery, sex, female, and horror. Or rather, glorie descended, one of several new words improvised by Oxford don John Wycliffe and his band of translators for their controversial English-language version of the Latin Bible. The word’s first appearance is in Genesis, in the story of Joseph. The best-loved son of Jacob, son of Abraham, and owner of the famed coat of many colors, Joseph is sold to a passing caravan by his envious brothers, but despite years of exile, slavery, imprisonment, and even sexual harassment, his gift for interpreting Pharaoh’s dreams eventually lands him a plum posting in charge of Egypt’s royal granary. Later, when Joseph encounters his brethren, now starving — it is a time of famine, just as he predicted — he instructs them to take word home to their father:

Lo! youre iyen, and the iyen of my

brother Beniamyn seen, that my

mouth spekith to you;

telle ye to my fadir al my glorie, and

alle thingis whiche ye sien in Egipt;

haste ye, and brynge ye hym to me.

[Genesis 45: 12-13]

Jacob comes to Egypt to see Joseph’s unlikely success for himself, and brings the Israelites with him. (This move would not go entirely well for the Jews, but that’s another story.) In Genesis glorie attends to the crosser of borders, the exile. It belongs to the immigrant, with his neatly tended warehouse of wheat.

Wycliffe’s translation was undertaken in the chaotic aftermath of the Black Death, a time of epic realignment, from which new classes, new nations, and new literatures would spring. It was composed at exactly the same moment as The Canterbury Tales, and if the new translation was dedicated to anyone, it was less the Father, Son, or Holy Ghost than the farmers, tailors, and millers whose entitlement, piety, and licentiousness Geoffrey Chaucer immortalized in his own vernacular text. (Wycliffe’s critics thought as much, bemoaning how “the jewel of the clergy has become the toy of the laity.”) Where the Roman Tacitus had celebrated the war song of the rebel Boudicca — “On this spot we must either conquer, or die with glory!” — and the authors of the medieval Annals of Wales attributed the victories of sixth-century Celts to a luminous king called Arthur, the translators of the Wycliffe Bible discerned a different majesty, stolid yet popular, the glory of those who survived when twenty million died.

What Wycliffe’s group called glorie had appeared in the Latin Bible as gloria. But the Latin Bible was itself the work of translators, and their gloria sat perched atop still older words in other languages. Doxa, for one, scattered throughout the original Greek version of the Gospels. The word had signified simple “opinion” or “belief,” but the Jewish scholars in Alexandria who translated the Hebrew scriptures into Greek in the first centuries BCE chose to render ha-kavod, Joseph’s glory, as doxa. The coinage lent doxa an air of splendor, as well as a kabbalistic register of prayerful submission. (“May my soul be like dust to all,” asks the daily Jewish prayer, dust and soul alike submitting to wind.) Glory is thus connected at the root not only to notions like paradox (refusing to submit to common sense) or orthodoxy (reflexively submitting to same) but also to a heterodox undercurrent in which divinity and mundanity are understood as contiguous. This is a thing-like glory, at best distantly related to a Wycliffe coinage like mystery. It is actually a form of anti-mystery: startling and immediate, like the stench of a family rotting in a plague-ridden cottage, or a sudden flash of gold.

Some mainline Catholic theologians of the same era saw glory in somewhat related terms, speaking of a gloria materialis. This was as an objective, etheric conductor, a class of matter across which the affirmed and exalted fact of God could be transmitted to the baser levels with all the force of a slap in the face. Gloria materialis was like a fifth element connecting earth, fire, water, and air to God. It was the iridescent fingerprint of the Creator on his creation, a holy residue that, like an oiled wick, could connect the flammable hearts of men to the spark of the divine. A few centuries later the first chemists would theorize another fifth element, phlogiston, an invisible substance thought to bind the other four in combustible configurations; gloria materialis could be thought of as a theological phlogiston. This kind of glory evoked the properties of circuits and currents in the pre-electrical age. It could suddenly render one speechless, the proverbial bolt from the blue. One could plug into this circuit willingly, or one could find oneself turned abruptly into its passive conductor, filled against one’s will by the grandeur of God. Away from the Church of Rome Calvin imagined something similar and called it grace, a downward pressure from heaven that could force an unwilling man to bend the knee. It was through grace that even the lowliest might find themselves saved.

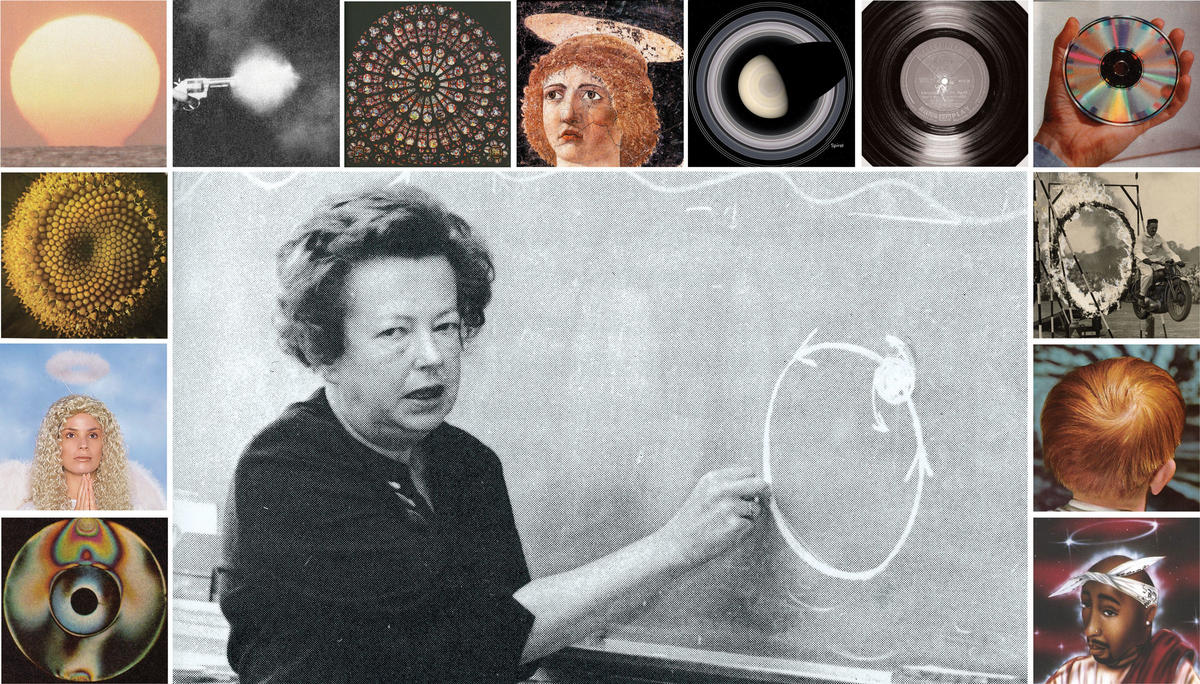

Wycliffe’s sense of a middling, almost humble glorie would lose its focus as later generations lost sight of the apocalypse that had engendered both them and it. Glory has come to accommodate a much wider world of meanings. Today we speak of glory in relation to winning seasons, paradigm-shifting technologies, roadside conversions, early adopters, sublime panoramic vistas (both natural and reproduced), and first brushes with abiding, transforming loves. And glory has become a channel for other, darker energies. Milton wrote in Paradise Lost of Lucifer’s doomed aspiration “to set himself in Glory above his Peers,” and we moderns feel the pang of deep, underlying sympathy. The louche terrorist Zero in Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1885 novel The Dynamiter quipped of his predilection for blowing things up, “Mine is an anonymous, infernal glory. By infamous means, I work towards my bright purpose.” And lo, across much of the English-speaking world, an opening in the partition between two bathroom stalls in a men’s room becomes a glory hole. Dictionaries variously define the glory hole as “a drawer or place where things are heaped together in a disorderly manner,” as an all-male space below decks on a ship, as “an opening in the wall of a glass furnace, exposing the brilliant white light of the interior.” Perhaps the term’s coiners were also thinking of the Latin diminutive gloriola — gloriole in English — which over the years has become a near synonym of halo. The same bright circlet now encloses the head of saint, sinner, and martyr without prejudice or distinction, an opening in the fabric of the world through which they transmit anonymously and alone to another plane. All of it is glory.

I came of age during the 1970s and Eighties in Cambria Heights, Queens, a quiet, quasi-suburban neighborhood of tree-lined streets on the extreme eastern edge of New York City. Our zip code growing up was 11411, a numerologically suggestive palindrome — four ones? One four? It could have easily been notation for a drum machine, the encryption of a rhyme. My family had come to the US in the mid-‘60s, fleeing the island of Haiti and the dictatorship of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. Cambria Heights and its environs made tidy safe houses for their aspirations, as well as for those of tens of thousands of equally mobile African-American neighbors. My parents had no intention of staying — no Haitian tyrant had ever held on to power for more than a few years, and they presumed they would soon go back home. But they were grateful to America. Back in Haiti my mother had been pregnant twice, but those “back there” pregnancies had produced stillborn twins (fraternal; one boy, one girl) and a weak, premature daughter, doomed to an infant’s burial. I was told the story of my dead siblings as soon as I was able to hear it. The moral I came away with was that I was not the firstborn; I was simply the first to survive. Sometimes I wondered whether they resented me the good fortune of my birth in exile, if they wished Duvalier had made himself dictator sooner.

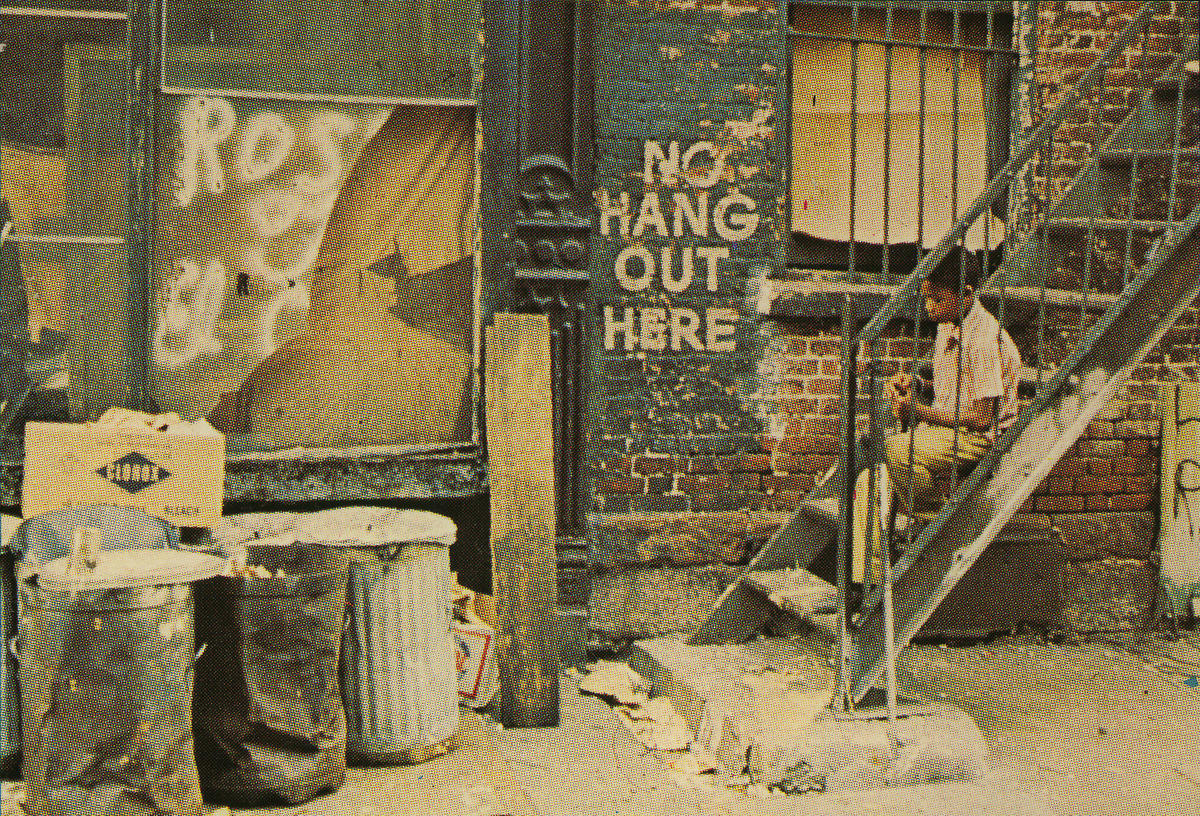

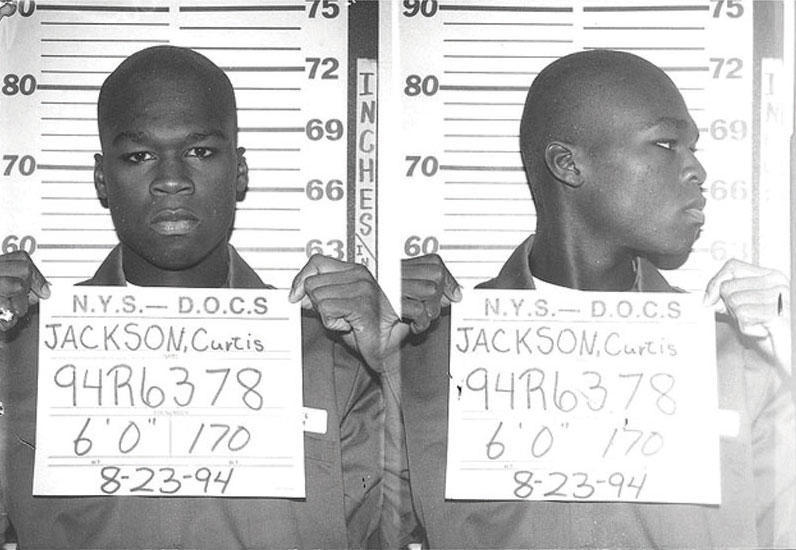

The then-defining traits of New York City in the popular imagination — subways, graffiti, blight, crime — were in the main hard to come by in our neighborhood. Public transit started running out of steam long before it got to us, the terminal stops of the subway system transferring bedroom commuters onto weak sister buses several miles to our west in Jamaica, and Queens’s sketchier nabes were highly specific and concentrated zones whose outlandishness only underscored their anomaly. Queensbridge Houses may have been the largest, most direly expansive public housing project in the United States, but it sat remote on the borough’s Manhattan-facing edge like a distant stand of foothills abutting a rarefied, skyscrapered promised land. Similarly, for most of my youth the suffering and violence in Queens’s worst precinct — the appropriately nicknamed Southside — was experienced largely through newspaper headlines, rhymes, and television news, though it was merely a long bicycle ride away from the major landmarks of my adolescence. From the mid-Eighties through the mid-Nineties, Southside was ground zero of Queens’s crack epidemic; Curtis Jackson, aka 50 Cent, twenty-first century hip-hop’s biggest-selling robber baron, grew up there. Long before the entire world knew the trivia of 50 Cent’s comic-book origin — shot five times while dealing drugs in Southside! In the face! — it was well established that a kid from Cambria Heights or Saint Albans would have to be crazy to ride his bike out there. It would get tooken, as the West Indians liked to say.

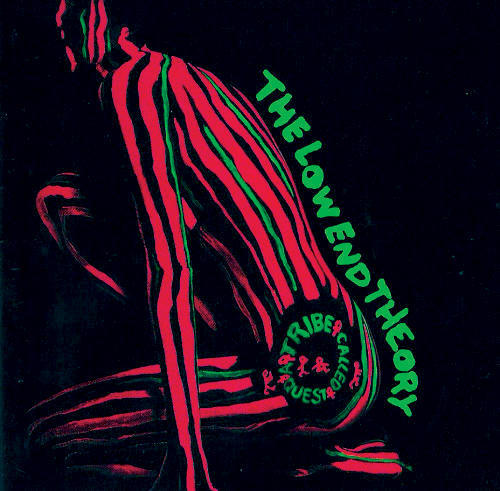

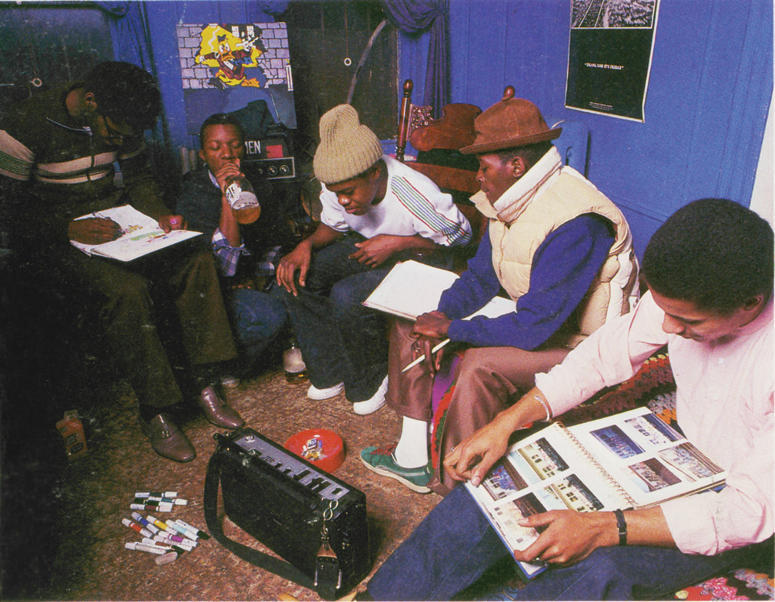

Our part of Queens was as far away from the urban centers of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx as it was possible to live and still consider oneself a legit New Yorker. Most of its residents had fled the big, bad core, but they had not run so far that it was unable to exert a powerful hold on the imaginations of their sons. We idolized and feared what we shorthanded as “The City,” fretted that our distance had diminished us, made us soft. We tested ourselves against The City’s hazards at the border when we could, but mostly we carried traces of it into our homes surreptitiously, for study. The years of my growing up saw the birth of hip-hop in the United States, and New York is the genre’s Garden of Eden, but Queens has always played the role of stepchild in these histories. (Even bucolic Staten Island would eventually be redeemed by the esoteric exploits of the Wu Tang Clan.) My part of Queens played an honorable role in Eighties hip-hop — I can claim to have seen local heroes Run-DMC at more than one block party before they were famous — but there was always a sense that my local heroes were tainted or limited by the underlying good nature of their origins. Even in the Eighties you had the feeling that somewhere in The City, likely in Manhattan, Brooklyn, or the Bronx, there existed a more powerful musical live wire, whose voltages and amplitudes ran differently than ours. The great MCs of Eastern Queens and Western Long Island — Tribe Called Quest, Public Enemy — made epic claims on our attention, but they tended toward the formal or political, their imprecations and choruses not quite the soundtrack to an anxious walk down an unexpectedly darkened alley. Although they would have their moment, we always had a feeling that they’d been born to be eclipsed by hard-cases from the West, even if the West was 50’s Southside or Mobb Deep’s Queensbridge.

At eleven or twelve my friends and I were simply too young to get on a train and witness such things for ourselves. But we had been able to intuit their existence through the music and chatter that emanated from radio towers atop the Empire State Building, maybe the World Trade Center. During the day New York was a fairly standard American radio town, but on Fridays and Saturdays the airwaves would undergo startling transformations. On weekends I would stay up way, way past my bedtime, alone with a primitive radio cassette recorder, obsessively listening to, taping, and annotating live hip-hop shows broadcasting from clubs in The City. It was painstaking work. Masturbatory. I retreated to my room to commune with the music the same way I might retreat with pornography, locking the door and projecting myself into scenarios and situations that were beyond my years and ken. Long before I had any real notion of sex or dating or manly peacockery and expression, I understood that the clubs in The City were playing fields where all of the above and more took place. When the DJ would cut the noise of a crowd into the mix, I pictured myself in the hot, darkened room, lending my voice to the mass, feeding out along wires to the radio towers and into the world, into my bedroom, the circuit complete.

Friday to Saturday, week to week, the mixes changed very little; whole months or seasons might be marked by songs that would appear in different locations in the mix on a given night, in different versions. But when something new appeared in the mix, it was like accidentally stumbling across the third rail. It was magic, a sudden and irrevocable shift in the fabric of the cosmos. I remember being disquieted by the regularity with which what I had believed to be the Greatest Record Ever could be eclipsed by another. How could such things be? Didn’t that mean that the thing I had loved just a few moments earlier was somehow untrue, unworthy? And didn’t that mean that the thing I was loving now was also destined to disappear?

In addition to confounding me, a new, hottish song also immediately sent me into a kind of informational panic. The DJs didn’t tell you what they were playing — it was a club mix, after all — so if you couldn’t intuit who the artist was or make out the lyric to a refrain, you would have to ferret the data out somehow during daytime hours. On my particular block lived two older boys with hobbyist DJ tendencies: Eddie, who played the good-natured, tough-guy protector to the younger boys, and Pete, who was far and away the biggest asshole in a five-block radius. Pete was a blond, blue-eyed kid — his parents were refusenik hold-outs from the Fifties and Sixties, when Cambria Heights had been an Irish and Italian neighborhood — who had survived and prospered by living out a highly specific version of black maleness with an exactitude and rigor that bordered on the Japanese, though it was all thuggery and bullying. Pete had more sneakers and Kangol hats than anyone we knew and was by far a better and more knowledgeable DJ than Eddie, but consulting him was always a last resort. It brought risks — of ridicule, mostly, though also cartoonish physical assaults involving wedgies and Indian burns. Even his eventual redemption was lifted from a certain colored set of pages. Pete converted to a strain of Sunni Islam popular with African-Americans. He lives on the same block to this day, holy and sanctified, his mother and the kids from the old neighborhood the only people allowed to refer to him by his Christian name.

In any case, at a certain point on Friday and Saturday nights I invariably found myself without guides. There were two mixes each weekend night, an 11pm to 2am hip-hop mix and a 2am to 4am house mix, and I would listen to both, cataloguing and recording songs. But in the dead of night, when the house music started, I had nowhere to turn. In the aftermath of disco, most dance music had become associated in our young minds with homosexuals, and neither Eddie nor Pete had much truck with the gays. I would sit in the dark, unnerved and unmanned by the keenness of my interest. I feasted on the orchestral flourishes of the house music then in vogue, the gospel-powered wails of wronged and hopeful black women. It was a vicious cycle: I knew I would never be as tough as Eddie (forget Pete or the kids who lived in The City), so I felt a kind of ecstatic release from the pressure of manly expectation when 4/4 beats and outsized vocals issued out of my radio. But this in turn only further undermined my claim on the 11pm-to-2am slot. I worried that someday I would have to make a choice between mixes, and it seemed unfair, rigged even, a choice between two forms of failure.

Still, the house mix was too compelling to turn away from. I was fascinated by math as a kid, and I would often try to graph the mixes on quadrille paper, assigning admittedly arbitrary values and lines and algebraic expressions to beats, vocal lines, crescendos, and fades. This work was easier with the already schematic dance music, and I would often fantasize about working backwards from a graph and creating a song from it. The pictures always struck me as beautiful, futuristic, graffiti-like, and I wondered what the graph of the Greatest Record Ever might look like. I understood from my readings in physics (another interest) that scientists were on a quest to find a grand unified theory that could explain and encompass everything, and I imagined that such a thing must exist for music, too, a graph of the perfect, hidden beat. This notion seemed to solve the problem of the Greatest Song Ever, as whatever song I loved at any moment could be understood to be an aspect or piece of the Perfect Song, with some lines and equations omitted or mathematically transformed. The next Greatest Song Ever didn’t erase or eclipse the previous one; they were all the same. The upshot, of course, was that I might have to keep listening, cataloguing, and graphing forever. Saturdays and Sundays I would lay in bed well past noon, more haggard than any child of relative quiet and privilege should have been.

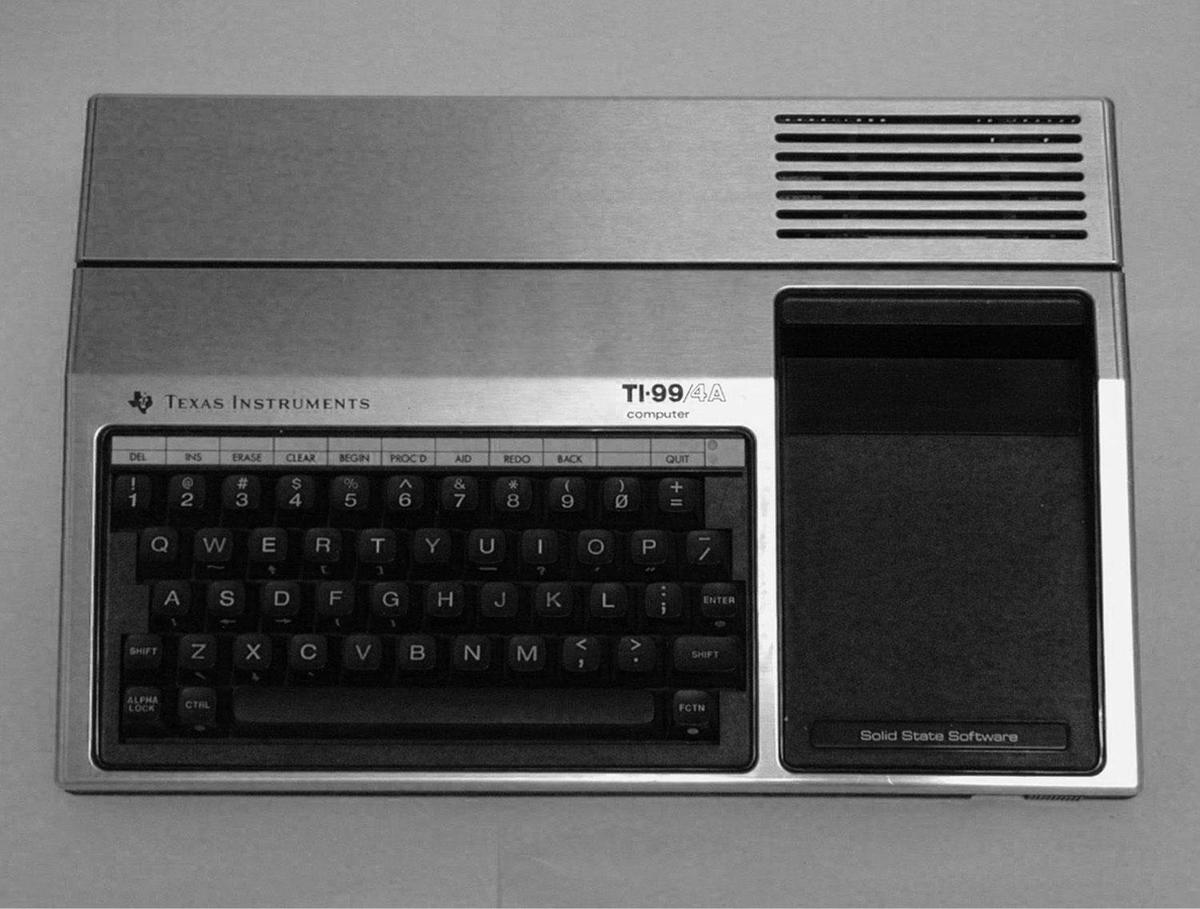

As my radio scanned the ether for signs of newness, I was not so much Joseph discerning the true shape of Pharaoh’s dream as Noah, building and collecting, hedging my bets against some gathering storm. (My parents were exiles after all; they had been chased across the sea.) I didn’t know what I was making, to be honest, but I knew that this unknown thing’s construction entailed an awful amount of work. I was going to need help, tools — better tools than pen and graph paper and cassette recorder. My parents had been loath to buy me an Atari. They worried it would come between me and my studies, they said. So I talked them into buying me an expensive personal computer by telling them that it would help with my studies.

I eventually settled on a black-and-silver machine made by Texas Instruments. It was a terrible choice, really, doomed from the start; the TI was introduced in the early '80s, only to be quickly eclipsed by Commodore 64s, IBMs, and Apples. Its one noteworthy feature was that it came with a then-impressive speech-synthesizing peripheral, a side-benefit of TI’s only successful line of consumer electronics: the Speak and Spell talking vocabulary tutor. On more than one occasion I stayed up until dawn, playing the speech-synthesizer against the radio, making the computer talk to me, recite lyrics in various electronic voices and accents. Listening for an echo. I didn’t know it at the time, but Texas Instruments had gotten its start in much the same way as a WWII-era maker of seismological devices, using reflected sound to pinpoint buried petroleum fields and the occasional silent-running German submarine. Giant pistons or explosive devices would beat against the curve of the earth as if it were an eardrum, seismic waves carrying back echoes of pharaonic riches. Like Joseph after all.