Mohammad Shirvani’s first feature film is an intimate diary that mixes real life and screen life with experimental abandon. Welcome to Big Brother, Iranian style.

I am born

I shall die

I think that maybe I was dreaming

I was dreaming

I was asleep

As Nahf (Navel) comes to a close, the great Iranian singer Farhad’s voice drifts in, lending an ethereal ambiguity to the urbane DV imagery. Director Mohammad Shirvani, who compares Farhad’s gravely tones with Tom Waits’s, signs off his audacious debut feature with a return to the lyrical style of his award-winning shorts

Shirvani made a name for himself when his first film, Dayeteh (Circle), was selected for Cannes Film Festival in 1999. In The Cherries That Were Canned (2002), which played at festivals around the world, his sensual style came of age; in 2003, master filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami described Iranian Conserve as “the best Iranian short since the Revolution.” In Navel, his first feature, Shirvani sought to break with tradition by making an “independent and ‘underground’ or experimental” and “deeply personal” film, one that expresses his mood of the past two years. Perhaps it goes someway to describing Iran’s, too.

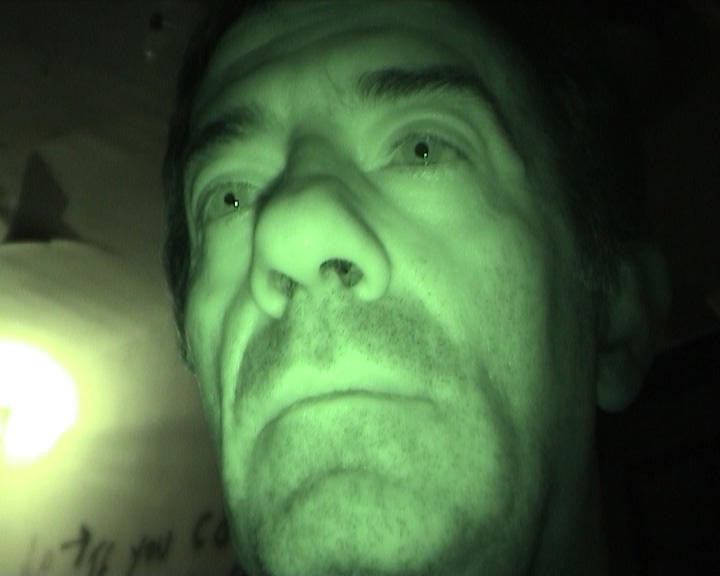

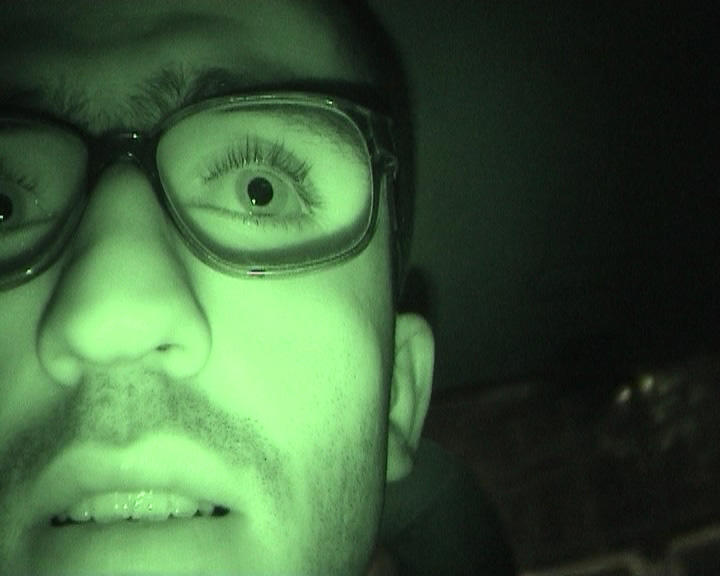

The feature opens with a baby being “unborn” back into the mother’s womb — grisly footage that sets the avant-garde tone. From then on, the imagery is shot on DV and night-vision camera, around the streets of Tehran and in the house that the five characters — four men and a woman — share. There’s plenty of standard DV red-eye and shaky camerawork, but the footage is surprisingly restrained, from the green-tinged night shots to the sepia-toned DV work; this was the result of weeks of test shots plus color correction in Paris and transfer to 35mm in Switzerland. Iranian-American Mana Rabiee plays Chista, a young woman recently returned to Iran after years abroad, whose Farsi is less than perfect. Chista is reeling from a break-up with ex-love Arshi; feted as a single woman, she at times “plays” with her housemates, who are variously awkward, affectionate or flirtatious in her single-woman presence. Mani (Ali Hooshmand), the central character and owner of the DV camera with which the five film themselves, is nostalgic about life’s lost opportunities. He (unsuccessfully) competes for Chista’s affections with laid-back billboard artist Khosrow (Khosrow Hassanzadeh), a divorcee with a young son. Meanwhile, Reza (Reza Hassanzadeh), a former cleric, struggles to come to terms with his faith in this very modern kind of Tehran. All four attempt to protect Aboozar (Aboozar Javanmard), a young innocent from the country completing his military service.

The boundaries between life in the house and on the screen were blurry to say the least — indicated by Shirvani’s tendency to refer to the actors by their on-screen names. “[The actors] didn’t know each other beforehand,” the director explained to Bidoun. “Everyone first met Mani at a party and Chista came from New York, and was faced with us accidentally.”

The actors’ lives fed into their on-screen personalities: “I found Aboozar during a trip to the north of Iran. Reza Hassanzadeh joined us after leaving his studies at a religious school. We created a [real] ‘home’ for four months before shooting began. The actors brought some of their personal belongings to their rooms, and they gradually came to ‘believe’ their new life.”

Mana Rabiee concurred: “Navel was a sixto eight-week-long commitment that turned into a ten-month odyssey. We really did live together, complain about household issues together, forge alliances and enemies and all of the ensuing gossip, and bond over an endless stream of cigarettes.” As could be expected, improvisation played a pivotal role. “We never presented any dialogue on paper to the ‘actors,’” Shirvani said. “They would repeat dialogue several times on set and become ‘conscious’ of their role.” From an actor’s point of view, Rabiee elaborated, “it’s fair to say that we went into each scene in the dark. To a large extent we co-opted those characters into our own personalities and life realities.”

The result is an unusually intimate diary in which the characters share songs and poetry, discuss their lives and loves, and touch on “taboo” subjects such as sin and relationships. Navel has no plot or storyline as such, but is more a series of conversations amid symbolic, stylized sequences. One scene places Chista, dressed in white, among a sea of black chadors, emphasizing her difference and loneliness as an “in-betweener.” Mani, nostalgic for bygone days as a deep-sea diver, dons his underwater gear in the bath. Shirvani manages to convey the hopes and desires of each of the five housemates; even though the cameras flit from scene to scene, it’s possible to develop a depth of sympathy — particularly with Mani and Chista. This familiarity is aided by “interviews” the characters do with each other and with themselves, and by the close camerawork: we feel we’re there, sharing their secrets.

Shirvani describes the camera as having a “multiple personality”: “The camera ‘befriended’ [the five] and became another housemate, it’s like the sixth member of the household and allows [us] to see the other five’s private moods. They don’t know each other [very well] and the handycam helps them become closer to each other.”

This produces a layered effect: we watch them watching each other. In one scene Mani films Khosro, up on scaffolding, about to paint one of Tehran’s infamous political billboards; we watch through the camera’s viewfinder. The camera also acts as a confessional tool, Big Brother style, culminating in an intense scene in which Chista addresses a love (and loss) letter to her ex-boyfriend Arshi. Rabiee told Bidoun that she shot the scene alone in the room, with only the barest script to follow. Mani refers to her ajar door as a “veil” between them but alone, Chista removes her hejab and directly addresses the camera: this is as far removed from traditional post-Revolutionary filmic grammar of the “averted gaze,” long shot and modesty required by the “presence” of unrelated spectators (as described by scholar Hamid Naficy) as it is possible to get.

Navel attempts to paint a complex picture of modern Tehran — a city in which, as Shirvani points out, young people are beginning to live together, away from the family; marriage is being left later and later; and divorce rates are shooting up. Despite their openness, the men are shocked by the young Aboozar’s furtive filming of women in a private garden while Reza, the ex-cleric, is troubled by the presence of Chista, a single woman in a house of men. Mohammad Shirvani set out to make “a simple film that didn’t adhere to general rules” and is disappointed — although he cannot exactly be surprised — that it has been banned in Iran. Not that Navel breaks entirely with Iran’s illustrious film history: it lies within the genre of fictional documentary, of a film-within-a-film, and refers to the neorealist style of Kiarostami. “It’s not enough to say it’s an Iranian ‘film within a film,’” counters Shirvani. “But it does refer to the Iranian version of ‘reality cinema’ in that it tries to create a ‘second reality’ without descending into simple reportage.”

Due to its experimental nature, Navel is as unlikely to be picked up for distribution in the West as it is in the East. But it should get some airtime in international festivals — at least, in those bold enough to diversify their image of the “traditional” Iranian festival film. Indeed, Shirvani’s film couldn’t present any greater contrast to the whimsical tales featuring children and the countryside that made Iranian cinema the darling of the festival circuit.

Nahf (Navel), 2003. Directed by Mohammad Shirvani (Iran). 85 min. Contact Robert Richter (robert.richter@datacomm.ch) for further information.