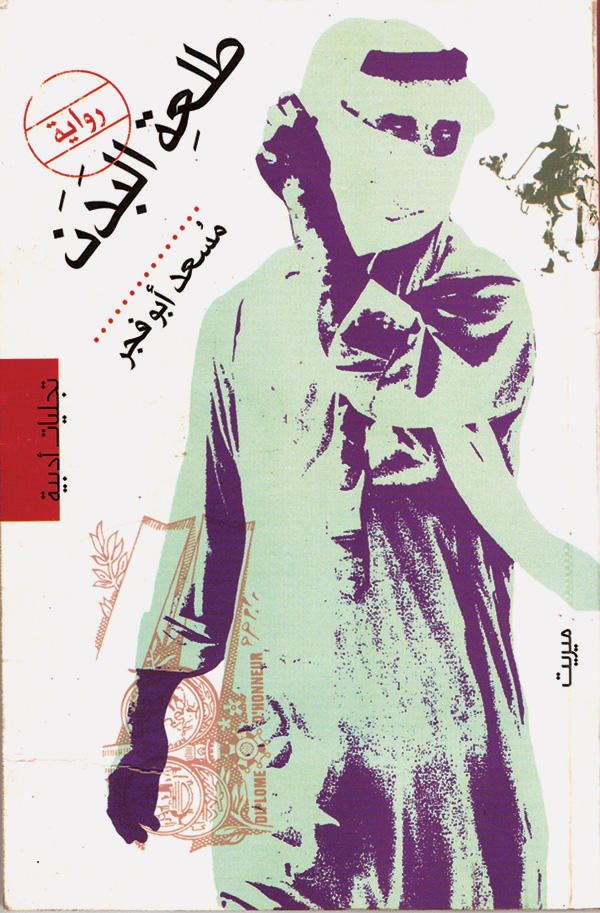

Tal’aat El Badan

By Mosaad Abu Fajr

Merip, 2007

Arabic

Over the past two decades, a trend known as the “literature of the desert” has emerged in contemporary Arabic letters. A treatment of desert life and a focus on the anthropological details of desert cultures are its defining features. Writers such as the Saudi Abd El Rahman Munif, the Libyan novelist Ibrahim El Kony, and young Egyptian writer Miral Tahawy are all exponents of the genre. Munif’s rigidly political perspective focuses on the demographic and social changes wrought upon Bedouin society by the appearance of oil, while El Kony attempts to trace the mystical and existential dimension of Bedouin life, and Tahawy presents a detailed depiction of the life of a wealthy Bedouin family living on the borderline between desert and countryside, as told from a female perspective.

Mosaad Abu Fajr’s debut novel Tal’aat El Badan, however, is quite different amidst this crowd. Abu Fajr’s focus is on the nomadic Sinai Bedouins, wandering between the Sinai desert and the expanses of Palestine through porous and imprecise borders drawn over the years by the various occupation forces, Ottoman, British, and Israeli. He looks at how the tumultuous political history of this region has played a violent role in shaping the lives of these tribes. Abu Fajr’s most important contribution is his attempt (not wholly successful) at introducing through the novel a new individuated Bedouin subjectivity.

The novel opens with the narrator contemplating his face in his pickup truck’s side mirror, describing a scar that his mother, under the advice of the tribal fakir (a sort of local witch doctor), had inflicted on him as a child to protect him from harm. With this image Abu Fajr boldly lays down the first details of what promises to be a complex portrait of a character and a society. Unfortunately, it’s a portrait that by the end of the novel seems incomplete.

The conflict of the Bedouin with the world around him is what motivates the action of the novel. Abu Fajr charts the tense relationship between the Bedouins of Sinai and the centralized Egyptian government. When narrator Rabie’ and his friend Ouda contemplate a historical object at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, depicting the pharaoh of Egypt humiliating a Bedouin on one of many punitive campaigns, the two friends are gazing into a past that only leads them back to the present, where the brutality of police officers is a daily reality.

But still, the Bedouins aren’t depicted solely as victims. Abu Fajr honestly portrays their disdain for the peasant dwellers of the Nile valley. “[The] Bedouin is willing to give up his life for freedom,” the narrator says, “while the peasant forfeits his freedom for life.” The free Bedouin is pitted against the peasant, who succumbs to the central power of the Egyptian government, which in turn grants him the irrigation rights to farm his land.

Freeform associations between different voices and registers propel the text; the personal history of the narrator and his friends are intermixed with the tales of their ancestors, revealing parallels among the different historical conditions under which the Bedouin experience has been formed. The opportunity to tackle the forging of an individuated subjectivity in relation to an external force, be it the state or the peasant, however, isn’t utilized.

Similar dynamics are evidenced in the author’s treatment of the tourist presence in Sinai. The presence of different Europeans is significant and is integrated, through his part-time work as a guide, into the life of the narrator; their presence, by extension, is seen as part and parcel of the contemporary Bedouin experience. Galit and Thomas, a Romanian photographer and a German Satanist, are two tourists whom Rabie’ joins in various small and ultimately ridiculous adventures. But the narrator’s voice remains embedded in its past, his subjectivity stuck between the tribal collective and his attempts to stand distinct from it.

Cairo, where the narrator spends his university years, is another lost opportunity. Although the city, in its overwhelming anonymity, is a prime environment for the crystallization of an individual voice, its presence within the text is faint. Rabie’ only mixes with his fellow Bedouins and his Yemeni friend Hemeid; even his colleague, Zohra, who falls in love with him during his student years, hails from Bedouin origins.

In Tal’aat El Badan, standard contemporary Arabic idiom is used in favor of classical poetics, allowing for an easier integration of the Bedouin dialect and the usage of a few Hebrew sentences without having to rely on textual clarifications or overwrought linguistic translation. In the case of the Bedouin dialect, Abu Fajr gambles on our growing sense of proximity to the culture to be able to decipher the dialect, while in the latter case he allows us to guess meaning based on the context, a task made easier by Hebrew’s phonetic similarity to Arabic.

Notwithstanding the dominance of the novel’s subject over formal aesthetic concerns, it’s still a decent read. But it needed more precision, greater rigor, tougher editing, and, above all, a stronger narrative voice. Interestingly, Tal’aat El Badan (literally, the arising of the body) is the name of a mountain situated in the heartland of tribal territory that bears more than a passing resemblance to a human body rising out of the sand. Similarly the hero of our novel remains, without much of an inner world, stuck like Hegel’s sphinx — while his head is lifted to the sky, he’s half-immersed in sand, a striking metaphor for the novel’s failure to represent a fully formed individual consciousness.