“You need to paint apples and beefsteaks. They fill you up, and then you get to sell the paintings, so what you have is art education as food supply, you know what I’m saying?” “Cassius” Al Madhloum speaks in a staccato rumble of enjoyable associations, the downtown Zurich bistro Café Perla filling with his marvelously deep, croaky voice, more typically associated with the patrician poise of strong silent types than the nervous soliloquies bubbling over in front of me. Cassius is a Jenin-born painter, a recent addition to the professional art circuit, first in the Middle East and the Maghreb, and now, possibly, Europe. Conversations with Zurich galleries are ongoing, hands are being shaken, proseccos sipped, nodding smiles exchanged, while friends are making the introductions (no, don’t bring any jpegs, just smile and do your croaky-talking-charm thing).

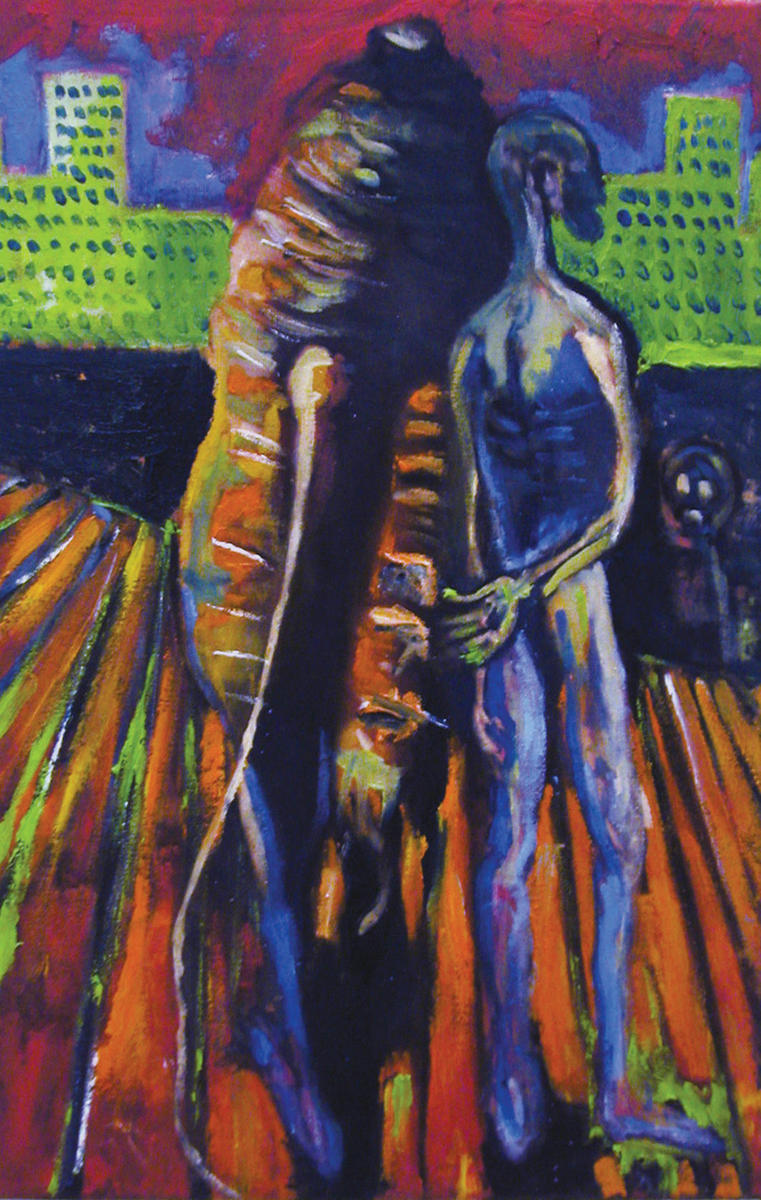

Cassius’s oeuvre has often been called “very formal” in temperament. Although empowered by the belief that it doesn’t take that much to paint, Cassius’s formalism is more heavy metal than flippant. His finest paintings include dabs of fluorescent red, silver glitter, glossy tape, or fields of darkest noir, which give a modern touch to the considered presence of international painterly traditions conveyed by drips, blobs, bars and bands. The thrust of what he terms “verisimilitude as gentle magic” is conveyed by the many subjects drawn from Arab and Iranian modernism, sometimes evoking the ways in which the mass media employ the same motifs. All in all, his work forms a handsome, if at times exaggeratedly conceptual reflection on the inevitability of reference.

Cassius doesn’t really admit to what are commonly termed artistic influences; instead, there are a number of artists — Thomas Kippenberger, Ingrid Serven, the late Leyla Al Mutanakker among them — whom he acknowledges as “role models.” He doesn’t respect his mentors for their artistic output (“Leyla, god bless her, she was many things, a designer, a marvelous cook, but she was not an artist”), but rather “for a way of harnessing the notion of art and bare life, art as bare life, not bare life as in [Italian philosopher] Agamben’s biopolitical gulag claptrap bullshit, but bare life as an existence perpetually on the margins of the institution. Taking life seriously through art, art as a model for doing and thinking, you know?”

Cassius has just stopped smoking, only last month, and his eyes are following every cigarette I light, to the ashtray and back. “So, Tirdad, have you read any Faouzi Rouissi? Rouissi is the man who introduced cultural studies to the Maghreb, dozens of studies of pop culture histories — I mean, he was the one who proved that Tunisians doing hip hop were not simply idiots, [that it was] not just false consciousness. I even came across an article where he’s tracing the science fiction paradigm in Arab soft rock.” He pauses, checks his watch, and I know I need to regain control of the interview but can’t bring myself to interrupt the captivating coffee table Castro show. “And so I attended a lecture of his in Tehran with my brother, my academic of a brother, and would you believe it, we couldn’t stay because my brother, of all people, was saying it was a bunch of university types trying to cash in on street cred.”

Cassius is wearing a corduroy suit of dark olive green, a new pair of Nikes and a heavy silver watch that makes clanging noises every time he emphasizes a point by thumping his left hand, usually twice, on the coffee table. Both Cassius’s parents are Palestinian. His mother, a housewife and an amateur boxer, once offered free daily lessons to women in the neighborhood, which explains both the pen name and the boxing glove leitmotif in the artist’s work. Cassius’s father was once a PLO functionary, eventually moving on to become a public relations liaison for the Norwegian consulate, and is now retired, working part-time as Cassius’s long-distance studio assistant. “I call him up and say, ‘Baba, I need something about space and time and technology, something with a ladder, something silvery you know,’ and he goes and paints it.”

Cassius emigrated from Jenin when he was eighteen, now living and working in various places in Tunis, Beirut, and even Tehran, where he just spent two years living with said brother, now a faculty member at Tehran University’s department of mechanical engineering. “So listen, do you know any Palestinian jokes? No? What a shame. We’re untouchable. No one makes Palestinian jokes in public. Not here, not in Tehran, not in the Arab world. Maybe in Israel. We’re noble victims, so no jokes. Anyway. A Palestinian, an American, and a Chinese walk into a restaurant…”

The joke is pleasantly xenophobic and quite uplifting. Very Bidoun.

“Listen, I’m going to tell you about this new project. You know they want to invade Iran any moment right? Well, me and this Swiss artist friend of mine, we’re opening a bar. All the whiskeys and Baileys and grappas and Johnny Walkers and Malibus lined up. The wallpaper, the furniture, the sound system, everything on standby. CD player on pause. The moment the troops come in, we just press play. So it’s a sort of temporary sculpture called Joseph Beuys Who the Hell is Joseph Beuys.” Cassius cracks his knuckles, twice. “I’m even talking to these guys who might do a band, called Cara-OK. They’re going to do medleys of hip hop classics, American underdog muzak from Public Enemy to Run DMC to B.I.G., just for the troops, right, because their music is our music, too.”

What Cassius’s supporters, even the undying enthusiasts, don’t know, is that over the last two years his most faithful clientele has been the Tehran lumpenbohemia, from the heroin dealers to the quasi-prostitutes to the fanzine philosophers. Cassius makes no attempt to keep this a secret. “They pay me with nighttime lessons in postexistentialism and street hermeneutics and sexual favors and amphetamines and so on. Sometimes we all wind up together around the kitchen table, sitting around having ultradeep conversations where we redesign the world from scratch.” He chuckles, a melancholic little chortle, and opens the Bidoun in front of him. “Apples and beefsteaks,” he mumbles, leafing through the magazine until he reaches an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist. “Art education as food supply.”