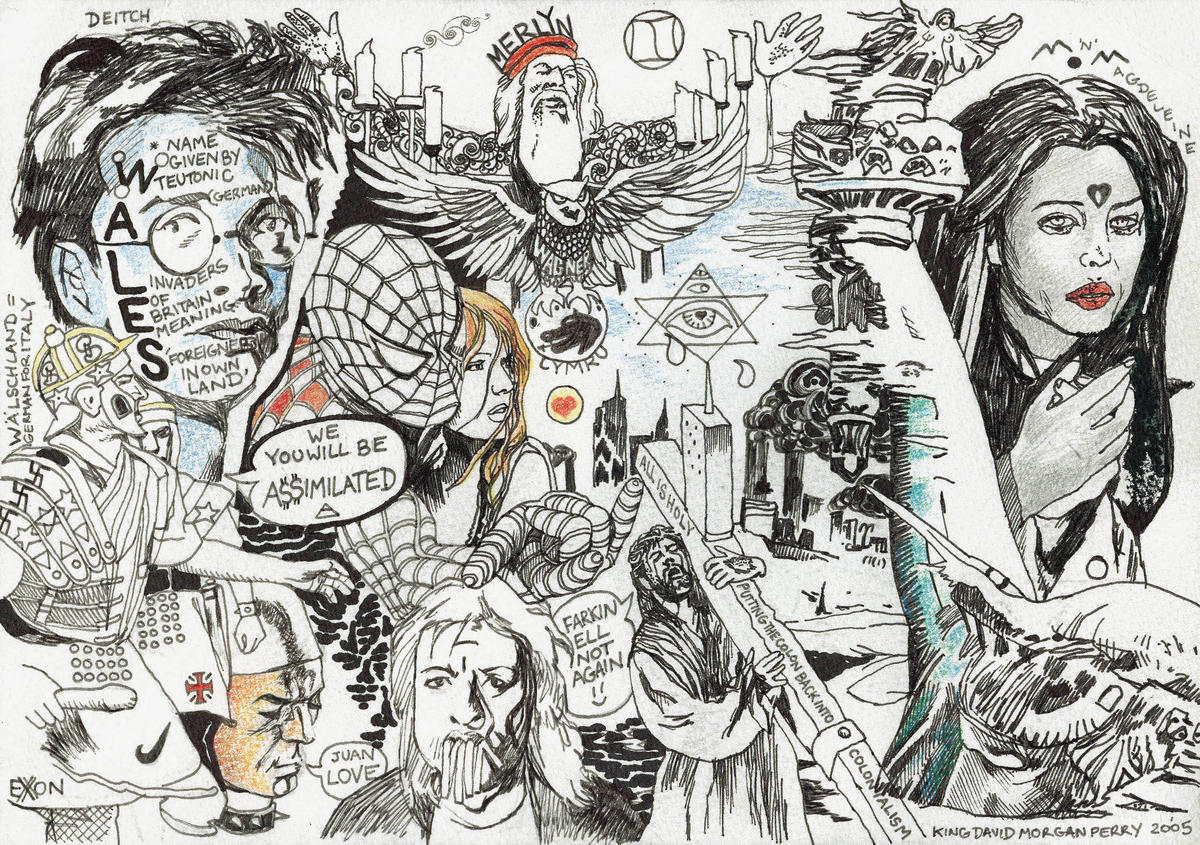

1. The Passion of the Christ

2. Spiderman II

3. Troy

4. The Last Samurai

5. Awkal Al Limbi III

6. The Day After Tomorrow

7. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

8. Alexander

9. Around the World in 80 Days

10. King Arthur

It’s accepted wisdom among left-leaning, Starbucks-dodging world-cinema buffs that the homegrown product offers the most authentic cultural experience. The favored ethnofilm would have battled against the might of the Hollywood-dominated machine from script to screen. Winning a place against the odds at a film festival, the plucky picture might then claw its way on to a limited circuit in London, New York, Paris, and other chain coffeehouse capitals; very occasionally, it might even score the odd screening on its home turf. But what about the films that the masses actually do get to see? Maybe B-grade action and Playstation-esque sequels say as much about a place; perhaps it’s the booming voice of the Dolby system that speaks the loudest.

The UAE hosts a film market that’s growing at an unusually rapid rate, last year accounting for some 65% of all box office takings in the Middle East. Hindi, Malayalam, and Tamil productions arrive in the country’s aged Indian cinemas a couple of weeks after their launch at home, and are popular with Emiratis as well as the dominant South Asian community. But it’s Hollywood films that have soared over the past few years. Columbia TriStar’s business in the Emirates, says regional boss Mark Braddell, increased by over 80% in 2003, and a further 30% in 2004, largely thanks to such “product” as Spiderman II. Saudi Arabia, of course, has no cinemas and Kuwait has the toughest and most unpredictable censors in the Arab world. The Iranian box office, thanks to government “protection,” is one of the few countries in the world where local films dominate, as is Egypt, the tired old powerhouse of Arab film production. The Lebanese still consume the widest variety of cinema, but it’s the Emiratis and their fellow expats who visit (and pay) the most, attracted by shiny, new multiplexes in every sparkling mall.

In many of its preferences, the UAE is no different to any other unmediated territory lacking the local film clout to challenge the Holly/Bollywood juggernaut. Star worshippers in a land overpopulated by celebrity! magazines, cinema regulars lap up the latest fluff; their picture houses occasionally even serve as a dumping ground for B-grade action that is straight-to-video elsewhere. This cynicism does belie the efforts of cinephiles to buck the system: Local filmmakers ply their wares at the annual Emirates Film Competition; 2004’s inaugural Dubai International Film Festival had many sold-out screenings; quality pictures such as Super Size Me, Before Sunset, Hero, and Dear Frankie are slated to have their turn at the multiplex over the next few months. Distributors, some now relocating to Dubai from their traditional center, Beirut, have begun pushing the boundaries in their selections for theatrical as well as a burgeoning DVD market.

The UAE’s most popular film ever is of course Titanic, a statistic that tells us more about the universal appeal of the sumptuous poor-boy-meets-rich-girl disaster-fairytale, the lowest common denominator of filmmaking, than it does about the many lands that the blockbuster conquered. But last year’s UAE box office comes with enough of its own quirks and tales of the Orient to warm the heart of any anthropologist — even the “retail anthropologists” that find their natural home in the UAE. (After all, this is “the place where malls go on holiday,” as British travel writer AA Gill memorably quipped.)

Globally, 2004 threw up two film market idiosyncrasies: Michael Moore’s Palme D’Or-winning Fahrenheit 9/11 and Mel Gibson’s biblical blood-and-gore number, The Passion of the Christ. Both fell foul of the nervy US studios, but went on to become unlikely blockbusters. Bizarrely, Passion scored better in the UAE, with its population of around four million, predominantly Muslim, than it did in Croatia and Hungary, slipping into the global territory breakdown just below Belgium. Passion also has the odd statistic of being the only foreign-language picture — if we take “foreign” to mean non-English, Arabic, or Hindi — to register a place in the UAE box office top ten. Filmed in Aramaic and Latin, the two hour–plus Christian epic made $1.4 million dollars for Gibson in the UAE, was the year’s number one, and became the country’s second highest-grosser of all time.

Gibson, through his distribution deals, had expressly forbidden any cuts; the UAE censors bowed to the Aussie evangelical’s wishes and passed it, despite having a few months earlier rendered Jim Carrey’s Bruce Almighty incomprehensible by cutting all signs of Morgan Freeman’s God — a factoid probably not mentioned to the legendary Freeman when he graced the Dubai Film Festival.

There are no statistics breaking down cinema audiences by ethnicity, but some of the enthusiasm for Passion could be accounted for by enthusiastic expat Christians (mainly from the Philippines, India, and Sri Lanka) embracing a faith experience rare in the UAE. But Emirates cinema audiences are disproportionately young Emirati lads, and Passion screenings attracted them and, say the distributors, an unusually high number of Emirati women. Was the enthusiasm down to the hyped violence? Interest in Jesus, the Muslim prophet? Possibly, but it was also overwhelming curiosity about “the other” being seen on screens for the first time. Some distributors added that, for some, going to see the film was also something of an anti-Israel stunt, following media puff about the film’s Jewish “villains.” Incidentally, DVD sales were very poor: Presumably, it’s one thing to happen across a Christian epic at the cinema, but quite another to own the film in your own home.

As for the award-winning film that ultimately failed in the electioneering game — beaten at the polls with the help of Gibson-loving God-botherers — Moore’s left-lite documentary was always going to do well in Bush-septic Al Jazeera territory. Playing for seven weeks, on a par with the latest Harry Potter (number seven on the 2004 UAE chart), Fahrenheit 9/11 came to rest at number fifteen, one above its box office ranking in the US. Worldwide, the film became the most successful documentary ever to play the cinemas; in the UAE, it was also the first. Escaping soaring summer temperatures, audiences were unusually interactive — whistling and applauding anti-Bush sentiments on the big screen. Up and coming distributor Gianluca Chacra, who picked up the film at script stage thinking it might repeat the success of the Bowling for Columbine on DVD — he was unable to get cinemas to screen Moore’s previous film — found himself propelled into the big league.

Chacra also found himself thrown into the middle of a media storm — one of those cyclones of paranoia whipped up by the special relationship between the Middle East and the US. Looking to prolong the Moore story with a new angle, a journalist from the trade paper Screen International put in a call to Chacra as he launched Fahrenheit 9/11 across the Middle East — everywhere, that is, except Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. He happened to mention that he’d had a call from Lebanese student supporters of Hezbollah, asking if there was anything they could do to support the film, to which he’d replied that they should just watch it. Being a former Beiruti, Chacra noted that their support was “significant in the market… and quite natural.”

Cue a hysterical response from the right and even moderate-leaning US media, who jumped at the chance to accuse Moore of garnering “terrorist” support. Pro–“war on terror” groups such as Move America Forward went as far as to charge Americans who chose to actually see the film with promoting the Hezbollah agenda. Former New York Times correspondent Clifford D May, now president of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, opined, “Michael Moore is the Heartthrob of Hezbollah… [He] fuels the fires of suspicion, prejudice and hatred that burn in the fabled ‘Arab street.’”

Michael Moore’s people kicked into gear, asking Chacra to release a statement denying any relations with Hezbollah and citing examples of “pro-American” (read Hollywood) films he handles. Never has the gap between the “US street,” so reliant on media hearsay and the fear factor for its impressions of the Middle East, and Arabs well-versed in the lingua franca of the all-action all-American blockbuster, appeared so great.

Perhaps life in the UAE has its fair share of fantasy already, but the UAE chart is marked in its difference from the rest of the world by the absence of animation — the world number one Shrek II only made it in at number 14, with the likes of Shark Tale even further down the list. Cinema-going in the UAE has yet to become a family outing. Meanwhile, the predominantly young, male multiplex audience, with its healthy appetite for stars and tribal action, propelled critically panned behemoths Troy and Alexander way up the list, not to mention Tom Cruise beating the Japanese at their own game in The Last Samurai (world box office ranking: 111; UAE ranking: 4). Key local distributor Salim Ramia, of Gulf Film, notes the UAE audience’s enthusiasm for action-adventures told with big screen brush-strokes of “honor” and “passion.” A visiting film anthropologist with a fondness for exotica might like to dwell on the Emirates’s recent history of dramatic inter-tribal disputes; we could also put the UAE cinema audience’s affection for epic dramas down to easy-digested pure entertainment, while noting that the biggest distributor of these Hollywood films also happens to own most of the cinemas.

Apart from these minor box office quirks, the only local oddity is that of the presence of an Arab film in the top ten. Unfortunately, for our Starbucks dodgers, Awkal Al Limbi is no plucky art-house number but the third outing for Mohamed Saad’s working class loser-hero Al Limbi, and representative of a popular yet asinine breed of Egyptian escapist blockbuster comedies. Al Ahram critic Mohamed El-Assyouti, like many despairing Arab film critics forced to write about populist cinema, was dismissive. “The only real fun is being had by the beneficiaries of all that box office money,” he sniffed.

And in the UAE, those box office dirhams continue to pile up. At the end of this year, two new megaplex cinemas are due to open in Dubai. The first, at the Mall of the Emirates, a 2-million-square-foot complex housing “the world’s first alpine-themed, all-inclusive indoor ski resort,” is a mere fourteen-screener. The second, part of the Ibn Battuta Shopping Mall, includes twenty-one screens plus an IMAX cinema. Chairman of development company Nakheel, Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, explained the inspiration behind the latter’s “authentic” wind towers, Persian domes and so on: “We have named the mall after the Arab hero which will… generate interest among the tourists who will find the mall exotic, entertaining, educational, and at the same time enable them to experience a themed, shopping experience.” At present, all the screens, like other cinemas in the UAE, will be dedicated to the all-conquering blockbuster; after all, the developer couldn’t have better summed up Hollywood’s intentions when it came to creating Alexander, Troy and other “Arabian” action heroes for the silver screen.