Walid Raad has a knack for tricks. A thirty-seven-year-old contemporary artist based between Brooklyn and Beirut, Raad has been known to confuse form and fact. He is the driving force behind an organization called the Atlas Group, which takes a serious and fastidious approach to the accumulation of documents related to Lebanon’s recent history in general, and the country’s fifteen years of civil war in particular. As such, Raad’s work has all the trappings of traditional documentary research. Yet appearances can be deceptive. Imagine Lebanese historians frittering away their time at the racetrack, gambling on finish-finish photos, while shells are being lobbed back and forth throughout the country. Imagine police investigators, tasked with solving the crimes of car bombings, but fixating instead on the particular trajectory of the engines launched from those detonated vehicles. Raad may not be pulling his viewers’ legs, but he may just be holding back the hint of a smile and cocking one eyebrow as if to suggest slyly, “You see? Things aren’t always as they seem.”

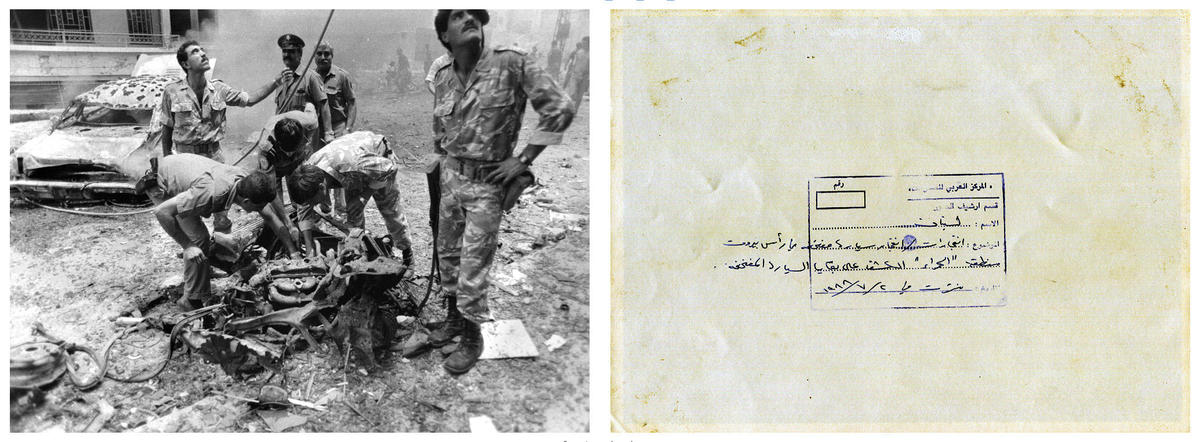

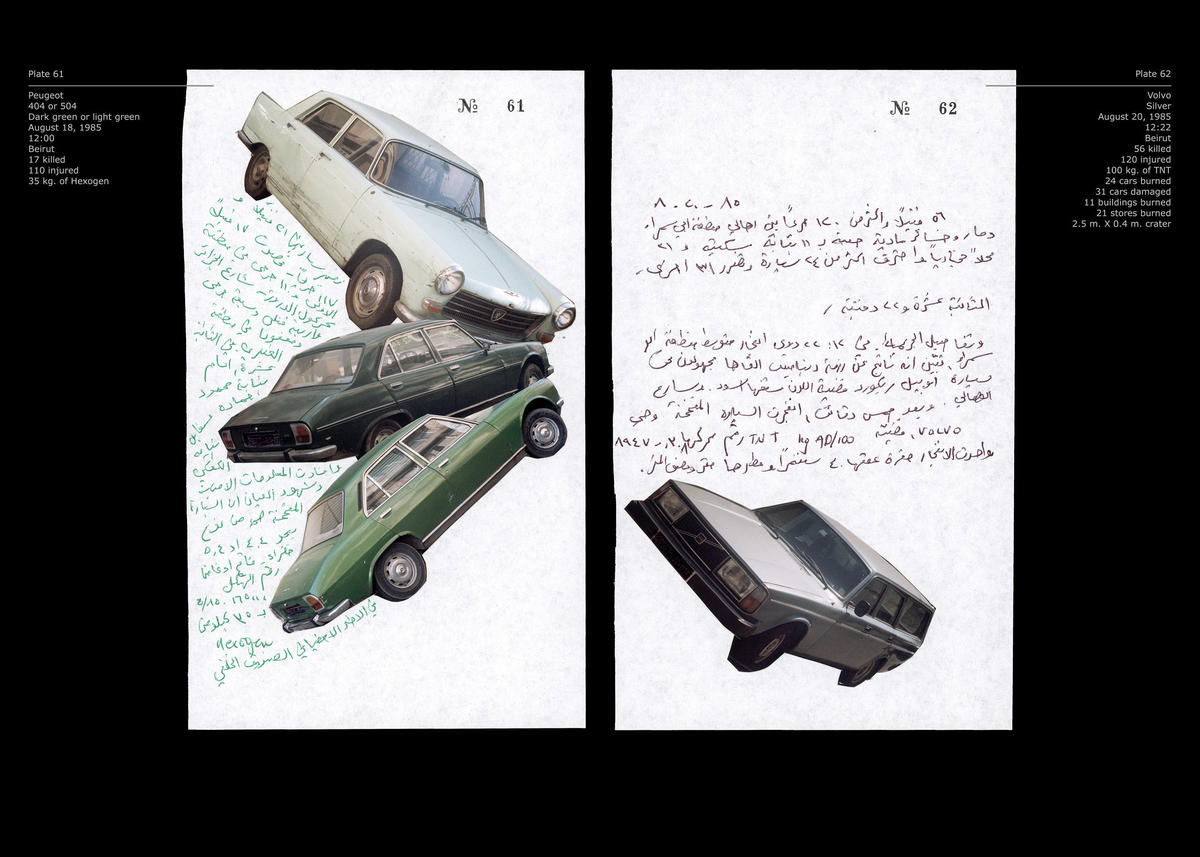

An Atlas Group production typically involves the following: press photographs, news clippings, interview transcripts, video footage, graphics, images, and text along with elements of performance, collage, digital photography, and video art, all rolled into the physical framework of an artist’s talk or academic lecture — a table, a microphone, a few lights, a stack of papers, a screen behind, an audience in front, a presenter in between. It is a rather sterile and austere environment, though packed to the gills with material. After all, the Atlas Group thrives on documents, filing them away into three distinct categories that comprise the organization’s archives. But those documents — some found, others produced — function not as emblems of fact or scraps of evidence to support the assertions of history, but rather as traces, as symptoms, as strange structural links between history, memory, and fantasy, between what is known to be true and what is needed to be believed.

As Raad’s brainchild, the Atlas Group erupted onto the art scene several years ago, afforded a space in such high-profile venues as Documenta XI, the 2002 Whitney Biennial, and the Venice Biennale in 2003. As to when the Atlas Group was established, and by whom, answers depend on how one asks, when and where. At this point, the story of the organization’s origins has settled on the year 1999, but previously Raad has tossed about dates from 1975 through 1996, along with the names of such co-founders and co-conspirators as Maha Traboulsi and Zeinab Fakhouri. In short, the Atlas Group started firmly in the realm of Raad’s imagination, but now exists in real, concrete terms. Its work has been documented, after all.

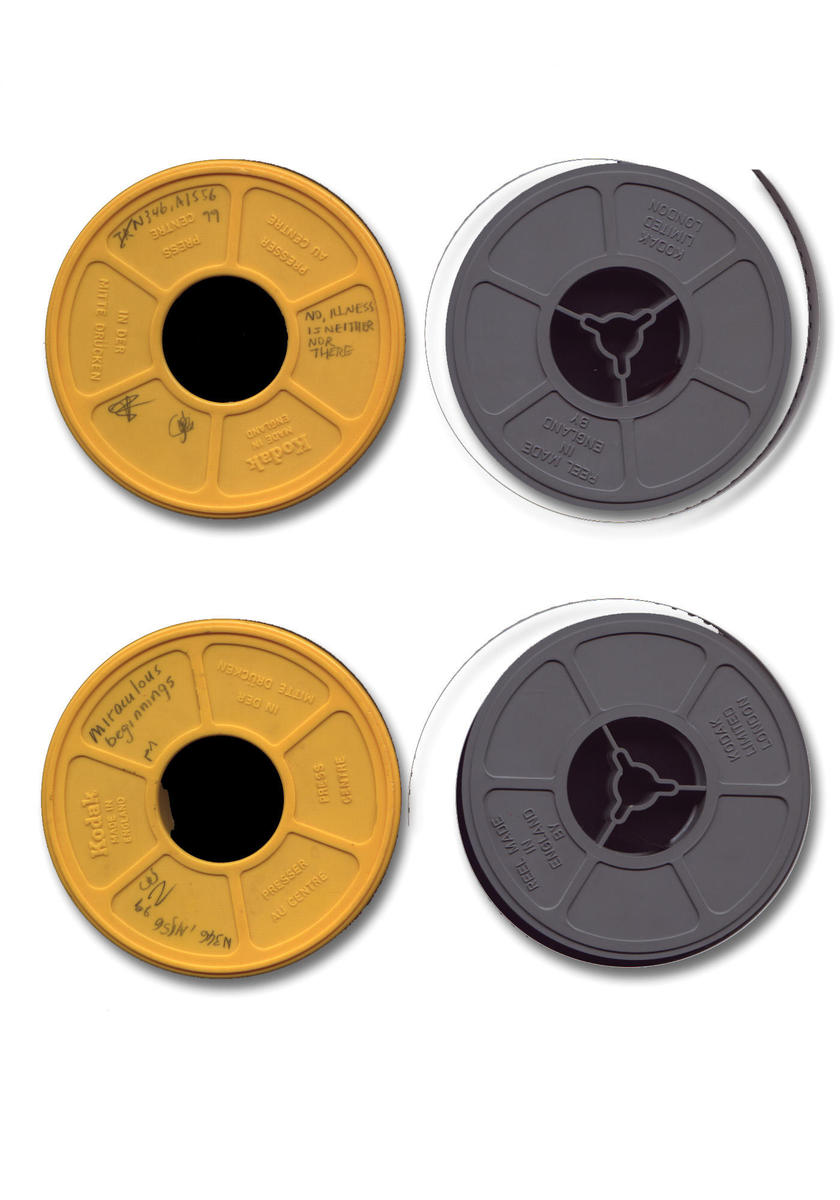

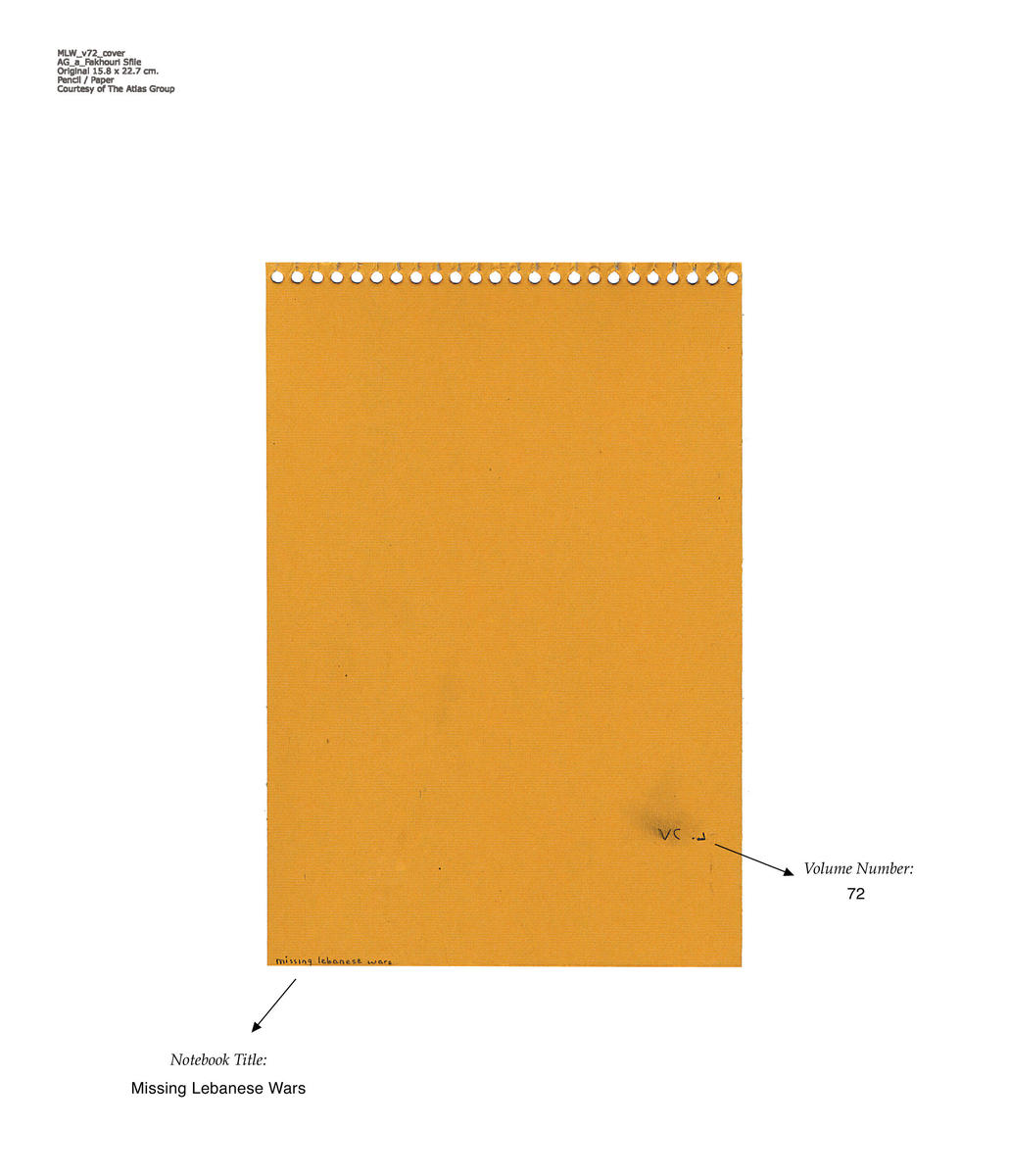

Among the Atlas Group’s archives are fifty-three video tapes that serve as testimony to the experiences of Soheil Bachar (a man claiming to be a sixth hostage held in captivity with five American men in Lebanon during the Iran hostage crisis) and 226 notebooks attributed to the historian Dr Fadl Fakhouri (a man positioned as the preeminent historian of Lebanon’s civil war). From selections of this material, Raad has constructed such multimedia works as Missing Lebanese Wars, Already Been in a Lake of Fire, and My Neck Is Thinner Than a Hair, all of which have been widely shown and critically acclaimed. That neither Soheil Bachar nor Dr. Fadl Fakhouri exists has preoccupied much of the critical response to the Atlas Group’s work, focusing on questions of authorship and authenticity.

To look at the Atlas Group as a conceptual artwork in and of itself raises interesting questions about contemporary art practices across the board. At the same time, however, one runs the risk of overlooking the nature of the documents and archives themselves, as well as the Atlas Group’s particular approach to them all. And it is here, underneath the set-up and the framework, where some of the most trenchant questions lie.

In collecting and archiving documents related to the contemporary history of Lebanon, the Atlas Group seeks to analyze as yet unexplored dimensions of the civil war (or wars) that raged through the country from 1975 to 1991. Along the way, it also digs into the manner in which that history has been written and communicated, the dominant narratives and prevailing discourses.

“The Atlas Group always works with existing documents,” says Raad, sitting at a café terrace on the eve of the group’s latest presentation, My Neck Is Thinner Than a Hair: Volume 1, January 21, 1986, which premiered in Beirut on May 6, 2004. “It has always involved material that existed in the historical world, and imagining the universe in which that material exists.” But the balance between fabricated and found documents has recently shifted toward the latter. A previous presentation of My Neck Is Thinner Than a Hair was sourced from the notebooks and photographs of Dr. Fakhouri, though many of the pictures had in fact been shot shortly before by Raad on the streets of Beirut. The latest installment relies almost exclusively on actual press archives.

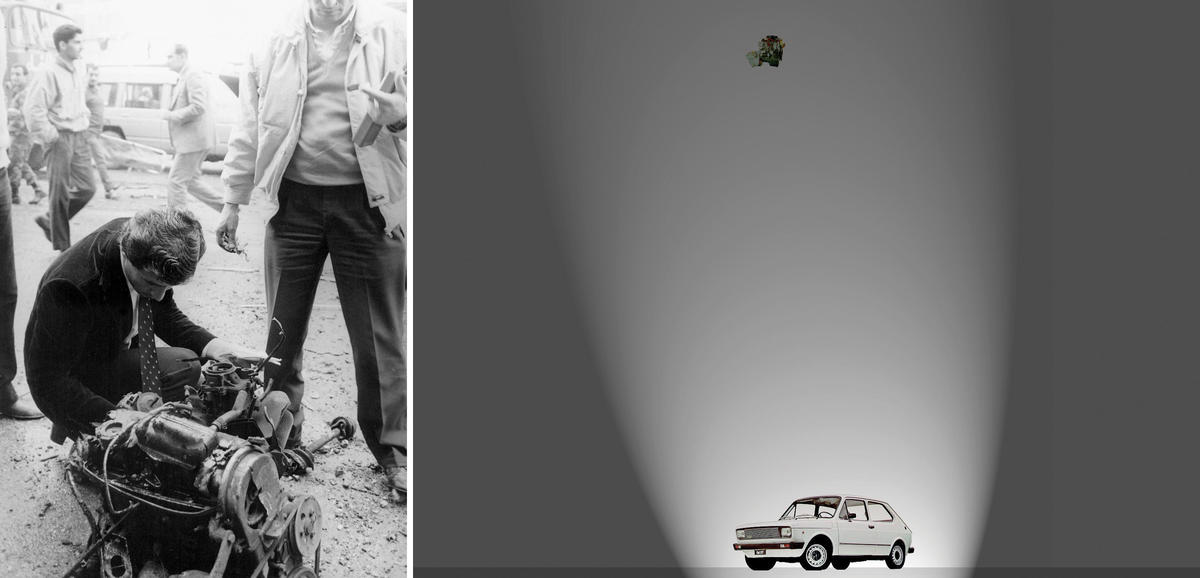

Generally, My Neck Is Thinner Than a Hair deals with the history of car bombings during the civil war. Specifically, it delves into one particular explosion, a car detonated in the Beirut neighborhood of Furn al-Shubbak on January 21, 1986. With colleagues Tony Chakar and Bilal Khbeiz, Raad formed a research team of sorts, gathering anything they could get their hands on, and limiting their search to a fifty-three-day frame. The three assembled press reports, television news footage, radio programs, and interview transcripts. They trawled through the neighborhood and interviewed people living there now about the bombing.

The Atlas Group’s ambition is not necessarily fame or the rehabilitation of a missing narrative or even the satisfaction that comes with comprehensive knowledge. “There is a constant identification of these historic events with the victims,” says Raad. “So the World Trade Center becomes about naming all the victims, showing the faces, telling the narratives, because that kind of victimhood gives you the right to speak and to be listened to with awe in a way that no other subject position permits. We’re not sure that we can yet listen to those positions, let alone make them manifest and say those are the people who died, these are their stories. They can be listened to but they will not necessarily be heard. Just like the buildings. You can go to Furn al-Shubbak, photograph it as much as you want, document it exhaustively — I’m not sure what you will know, and the same goes for the victims.”

In addition, the Atlas Group throws history itself into question. “There is this notion of chronological history where the past is certain, the present is certain, the future is certainly coming,” says Tony Chakar. “But there is no history. There is a huge catastrophe that’s in the making all the time. There is wreckage that is piled upon wreckage and that’s it. I don’t like when work I do or that Walid does is presented as an alternative history to something else, as if it is trying to find a place so it can evacuate the other history.” “I wouldn’t give up the term ‘alternative history,’” adds Raad. “But not an alternative history that is necessarily additional or that must be thought of as something that completes something that was missing. It might contradict, it might just add temporarily and then disappear… A reductive notion of traditional history is written as a chronology of massacres, of events, or a biography of participants. We are not saying history should not include this. We are certainly saying that history cannot be reduced to this… We are trying to find those stories that people tend to believe, [that] acquire their attention in a fundamental way, even if they have nothing to do with what really happened. Traditional history tends to concentrate on what really happened, as if it’s out there in the world, and it tends to be the history of conscious events. Most people’s experience of these events … is predominantly unconscious and concentrates on facts, objects, experiences, and feelings that leave traces and should be collected.” Those traces, in essence, are the Atlas Group’s archive.

It is true that among artists and intellectuals throughout the Arab world, and certainly among the artists and intellectuals in Beirut who are in some way involved with the Atlas Group, there is a frequent lament about the region’s lack of cultural documentation. There are few historical volumes outlining the area’s major artistic movements or prominent figures, and little impulse toward creating catalogues raisonnés of the work of modern or contemporary artists.

The Fondation Arabe pour l’Image (FAI), or Arab Image Foundation, may be the most obvious and ambitious effort to correct this dearth of documentation in the field of photography. But while Walid Raad is a member of the FAI, the Atlas Group has an altogether different approach to documents and archives. He deals with existing documents, but he goes further by provoking questions about the nature of their existence, and how one might imagine the universe in which they came into being.

In this, and in looking at the traces of war and the symptoms of trauma, Raad is not alone. Lebanon’s civil war was, by all accounts, a mess. And many would argue that the conflict was artificially ended but never resolved. The post-war period has been characterized by collective amnesia and a desire to rebuild the country as if it had never been destroyed. Nevertheless there has been little attempt to root out causes, analyze effects, or assess the possibility of true reconciliation.

It is telling that in much of the poetry written in Lebanon today, one can locate the image of Beirut as a woman careering schizophrenically from beloved to whore. It is significant that a good chunk of the novels written in and around the war years reach their climax at the airport, where guilt and fear paralyze a given character’s decision to stay or go. And more than a few visual artists have produced work informed by the war, in both direct and indirect ways. Mohammad Rawas, Samir Khaddaje, and Nada Sehnaoui are indicative of one generation coming to grips with the country’s recent history, while another generation of artists has also made its presence known. Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s ongoing Wonder Beirut project (in which the artists showcase postcard images of Beirut from the 1960s that have been systematically burnt), Lamia Joreige’s Objects of War (in which the artist records various people talking about material possessions that stoke old memories), and Akram Zaatari’s April 13th project (a sprawling documentary that is currently under way and set for completion next year, on the anniversary marking thirty years since the war began) serve as prime manifestations of such explorations.

In these projects, the impulse to fictionalize (in Raad’s cast of characters, in Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige’s account of a photographer named Abdullah Farah, or in Lamia Joreige’s ability to capture her subject’s self-contradictions) comes not from a desire to invent a new narrative that is essentially false, but from a need to question the veracity of memory, to make problematic that which is typically accepted as true, as fact.

“For a theory of the documents,” says Raad, “there’s almost a five-term strategy in terms of thinking about [them]. How does, for example, any object, experience, feeling, or event become a fact in the testimony of an eyewitness to an event of historical, collective dimensions? You have these terms, and all of them must be called into question.”

The Atlas Group’s documents do not mimic reality, Raad suggests, because that reality is itself suspect. “What we have come to believe is true is not consistent with what’s available to the senses,” he explains. “If truth is not what’s available to the senses, if truth is not consistent with rationality, then truth is not equivalent to discourse. Today, we find ourselves in a position where what we take to be true is what rings true at the level of the psyche … In Freud’s analysis of hysteria, when a subject undergoes a traumatic experience, what they come to believe has been little to do with what actually happened to them. But what they come to believe is certainly related to fantasies that are based on memories and that those fantasies are very important. You can’t just dismiss them and tell them, wake up, these are just fantasies. The fantasy captures the subject’s imagination and is his or her reality. So those are called hysterical symptoms. The hysterical symptoms bear no resemblance and have no real proximity to the event that caused them, and that’s what fascinated Freud … And I think the hysterical symptom then becomes, in a way, a document of something. And the interesting thing about it is that it’s not a question of returning to the origin, it’s a question of the future. It’s a question of the production of a narrative that rings true to the subject … The story you tell yourself may have nothing to do with what happened to you, but that’s the story that may cure you.”

The Atlas Group’s The Truth Will Be Known When the Last Witness Is Dead, consisting of two notebooks, two films, and a collection of photographs, is on view in the exhibition The Interventionists: Art is the Social Sphere, at MASS MOCA (the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art) through spring 2005 (www.massmoca.org). Raad is preparing to publish the first of Dr. Fakhouri’s notebooks as a book in October. His most recent essay, “Let’s Be Honest, the Rain Helped,” detailing answers to the questions raised during the latest presentation of My Neck Is Thinner Than a Hair and the film within that performance, We Can Make Rain but No One Came to Ask, can be found in a volume recently published by the Arab Image Foundation, The Review of Photographic Memory, edited by Jalal Toufic. The Atlas Group is back in London on October 29 and 30 with The Loudest Muttering Is Over, as part of LIFT’s Indoor Fireworks season at the Riverside Studios presented in colaboration with Forced Entertainment.