Bidoun Contributing Editor Shumon Basar remembers his formative time with visionary architect Zaha Hadid, who sadly passed away on March 31st, 2016.

It’s beyond belief—I’m beyond grief. Zaha Hadid has died? Zaha can’t die. That’s not the blueprint we deserve.

The plan of her life was—surely—that she’d outlive her hero, Oscar Niemeyer, who drew till the age of 104. Or the shape-shifting Philip Johnson, one of her great supporters, who kept reincarnating himself until he was 98. Architects like them don’t retire, because there is no wall between their life and their work. There’s no after to a life of work. There’s just the world before you arrived and the world you want to see during your life. The rest is for eternity.

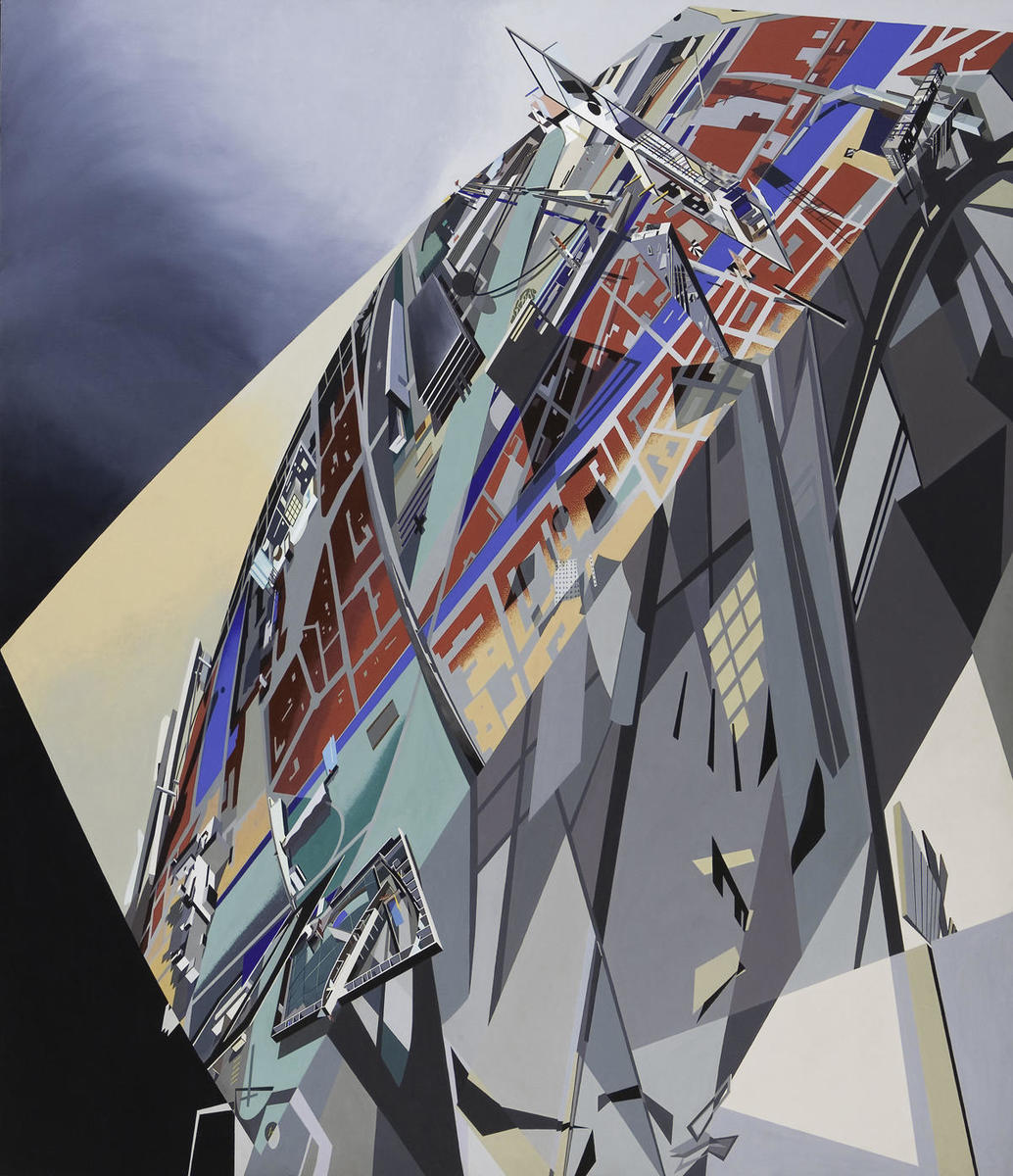

In an early interview with Alvin Boyarsky, Zaha said, “I almost believed there was such a thing as zero gravity. I can now believe that buildings can float.”

I always assumed she would defy the gravity of death, too. That those whorls of Issey Miyake or Yohji Yamamoto, wrapped around her with mathematical precision, accented by her obsidian, weapon-like jewellery, were more proof—as if it were needed—that she wasn’t really like the rest of us. Even though she was really interested in the rest of us (no one gossiped quite like Zaha).

Her approach—brusque and brutally honest—made a mockery out of the lame, xenophobic, misogynistic essentialism that dogged her in the press. Her name was forever prefixed by the adjectives “Arab,” “Muslim,” and “woman” in a way none of her contemporaries would be prefixed by “Occidental,” “Christian,” and “man.” I think it an insult to her, and to womankind, to refer to Zaha as “the most important female architect in the world.” In this her spiritual predecessor was the Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi—whose obdurate work out-toughs the toughest of male Brutalists, but never rhetorically engages gender in its making.

Right now, I’m thinking about our daily life some 20 years ago when I started work at her London studio. It was a converted school; we entered through the “Boy’s Entrance.” I was a fresh graduate. As such, I knew my way around post-structuralism but not much else. I was giddy to be at The Office of Zaha Hadid. I was convinced I’d been accepted into the heart of a living avant-garde. Here, I’d find the spirit of Malevich and Suprematism defiantly alive at the tail end of the 20th century, having survived the cultural wasteland of post-modernism and the pediments of revivalism.

My memories of those few years are vivid: the Broadway-level drama of Zaha’s arrival at the office each afternoon (which made Meryl Streep’s strop in The Devil Wears Prada seem positively quaint). How I never got Zaha’s cappuccino right (I’d never foamed milk before, OK? They don’t teach you that at Oxbridge). And the second-hand London black cab I used to drive Zaha around in (“Let’s stop at Maroush on the way.”) She also bought me designer clothing (style charity?). Shopping with her was so much fun.

But mostly I remember her incredible private kindness towards me, often forged in London traffic, inside that black cab, her in the back, and me up front, while I wondered, with all the intensity of a 22 year old, how did I get here?

Zaha did not see your preternatural age. All she cared about was whether your ambition was related, in kinship, to hers. (It also helped if you’d forsake sleep to better further it. Sleep is Kryptonite to architects.)

This private generosity was famously complimented by a default desire to publicly humiliate or berate you. But once I understood this was merely a lesson to affection’s paradoxical expression, an exercise in eccentric closeness, the jibes no longer felt like tiny spears, but soft snowflakes. I’ve probably never been so simultaneously cursed and valued at the same time.

I realised, even then, that this was a close-up experience with someone Really Historically Important. I stand by that. It should be a no-brainer. More importantly, for me, I was part of a totally unique world, full of singular individuals orbiting this relentlessly driven centre of gravity who was also so fucking hilarious. (Who else picks Drake’s Hotline Bling as one of their Desert Island Discs?)

Zaha went from cult famous to famous famous. Pop stars in silly hats believed a selfie with her made them even cooler. Because I had long left, there’s a lot less I can say about this expanding period of the office, as it grew into the architectural equivalent of a Chris Nolan film: indie blockbuster/boutique corporate. The future, as rendered in science fiction cinema, was also forever changed by Zaha’s futurism. Critical assessments aside, in the 21st century, the world caught up with Zaha’s visions. I’m so glad she lived to feel that glow.

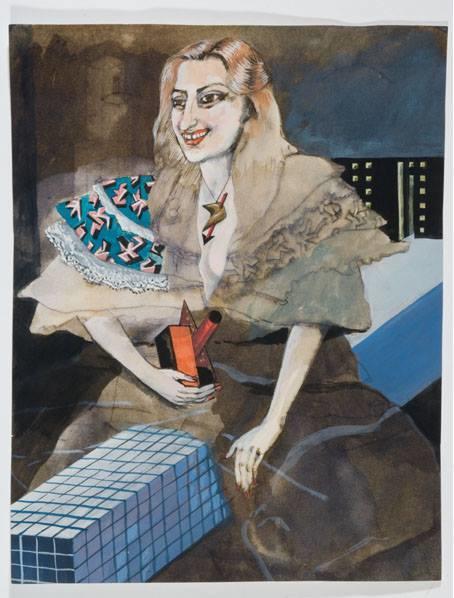

There’s a painting attributed to Zaha from 1983 (though in fact, most were collaborative efforts). It’s an aerial view of a warped earth—floating shards of colour, tectonic plates colliding—colonised by several of her unbuilt projects, flying apart or tied together by an unnameable force. This painting is called The World (89 Degrees).

That’s who she was. Who she always will be. The 89th degree.