Thessaloniki

First Balkan Biennial of Contemporary Art

State Museum of Contemporary Art

December 17, 2004–February 13, 2005

Over the last two years, the better-known contemporary art shows on the Balkans included: In Search of Balkania, Graz, 2002; Blood and Honey — Future’s in the Balkans, Klosterneubyrg/Vienna, 2003; and In the Gorges of the Balkans, Kassel, 2003. While Cosmopolis 1 was not the best, nor the most interesting among them, it had a number of redeeming qualities one must stress. First of all, the exhibition did not concentrate on the ordeal of the war and postwar in ex-Yugoslavia, nor did it focus on the Balkan history of hatred and trauma. It had much less blood in it, avoiding many Balkan clichés and age-old mythologies — what I would call “the Balkan blues” — which in turn made it easier to reflect on whether there really is a relevant artistic agenda in the region today. Finally, although the chief curator, Magda Carneci (Bucharest/Paris), is Balkan-born, she invited ten other curators to select and coordinate artists from their own home countries, leaving the event less suspect in terms of imposed identity and such.

Nevertheless, the event does lay claim to being the First Balkan Biennial of Contemporary Art, although it would be unfortunate if it adhered to a strictly regionalized format, either in terms of geography and artist selection, or in terms of some common agenda ascribed to artistic production in the region. Despite the shortcomings of the region-based biennial format, the only regionally defined biennial that seems to avoid these pitfalls at the moment is the Baltic Biennial, which has an approximate 50:50 ratio of from-the-region vs from-out-of-region artists.

It seems that the greatest curatorial challenge here is to first define a relevant agenda, and only then to invite the artists in a concerted effort to link a given region to other art centers, concerns, and even to other regions. Why not, for example, link the Balkans to the Near East or Middle East, rather than to try and fight the Balkans’ way into the mainstream European art world? The “Balkan way” involves stigmas and stereotypes that are all too tempting to use and abuse as convenient labels, and finally, for career benefits. If given a choice, no one in the art scenes of the region would accept the stigma of being strictly “Blood-and-Honey-Balkan.” And although everyone seems to agree that, in the present environment, it is hard to find an alternative to the instrumentalization of clichés, clearly the reworking of this marginal European region into an axis of broader relations is the more challenging and productive option.

In any event, the above aspects made this show less “Balkan” than other comparable large shows. Organizers were less concerned with a common Balkan identity than with current realities — realities marked by many promises and few clear objectives, diverse and shifting (if more stable than they ever were in the past fifteen years). For example, one might consider the eccentric political status of most Balkan nations. Until recently, Greece was the only EU member-state in the region, but also the most self-contained one: For a long time, I didn’t know any Greek artists, nor did I know anyone who did. Cosmopolis is not only part of Greece’s desperate recent efforts to make use of its EU status, but also to reintegrate culturally within the region. Then we have Turkey, historically the Ottoman “backbone” of whatever Balkan identity there might be, and thus a possible link to the Middle East. And yet the country is struggling for EU membership. The question remains whether Bosnia will survive with the help of the international community, and so on and so forth.

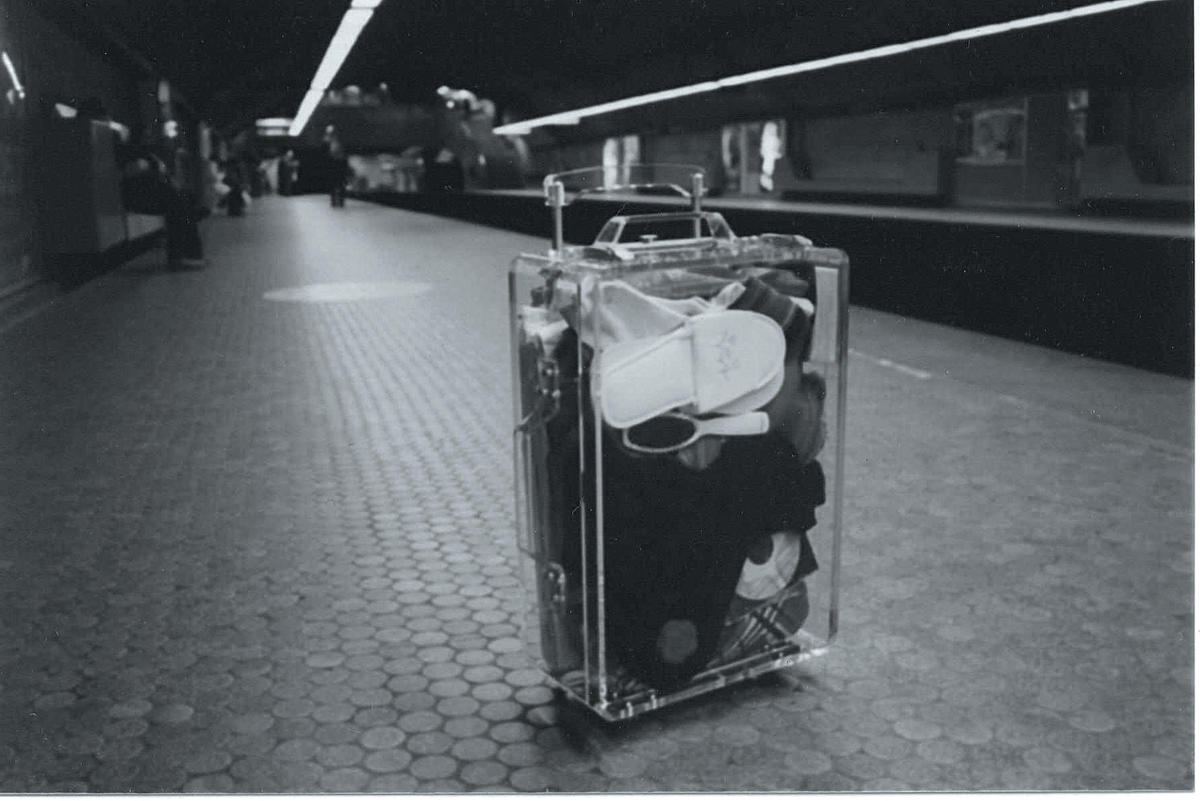

To come back to the exhibition itself, there are, I would say, three works that capture the essence of the show. Mircea Cantor’s (Bucharest/Paris) video The Landscape is Changing (2003) shows an informal demonstration of young people on the streets of Tirana. Instead of slogans, they’re holding mirrors on sticks, reflecting the surrounding physical reality in a distorted yet very amusing way. Flutura & Besnik Haxhillari’s (Tirana/Montreal) contribution, meanwhile, is nothing but a large, standard suitcase on wheels, but one that is made of transparent Plexiglas. This way, the authorities may rest assured that these two migrants have nothing to hide.

Finally, Danica Dakic’s (Sarajevo/Dusseldorf) cycle La Grande Galerie: Roma — Enclave Preoce, Kosovo (2004) consists of carefully composed photographs of local Roma characters in front of a mixed backdrop of landscapes and canonical paintings from the Louvre Museum, reminiscent of a famous work by Georges de La Tour. The irony of these beautiful prints is simple: The artist, who was once a refugee, is photographing people who have been vilified for supposedly collaborating with the Serbs in Kosovo, on behalf of the Kosovo Albanian ethnic population, which was itself repressed by the Serbian ethnic population in Kosovo, which in turn is ethnically linked to the Serbian ethnic population in Bosnia, which itself once repressed the Muslim Bosnian population, which happens to correspond to the artist’s background, and so on. Deeply theatrical in atmosphere, Dakic’s prints convey a sense of roles that are obviously changing.

Well, you know, it is the Balkans after all. Here, as the saying goes, it is not important if I am not doing well, the most important thing is that my neighbor is not doing well. Dakic seems to reverse this traditional “wisdom” of the region and I will follow suit by not mentioning my own work in this show, although I would very much like to.